Interview with SENAA architects

|

| Founders of the SENAA architecture studio Jan Sedláček (on the left) and Václav Navrátil. |

When did you first realize that there is something called architecture?

VN: Probably already in elementary school when I was gluing paper models from the ABC magazine prepared by architect Richard Vyškovský. I eagerly glued from small cottages and houses to an entire urban heritage reservation.

JS: I was similar and as a child, I glued airplane models. I got into architecture one generation through my grandfather who loved Gocárovy buildings, photographed them, filmed them, and wrote film scripts about them. In the 60s, together with the Hanak architect Pavlovský, he reconstructed a homestead in a village near Prostějov. When designing, they were freely inspired by F.L.Wright. They used stone walls, beam ceilings, and large windows. People in the surrounding area thought they were building some kind of store. I spent my vacations in this building, and even then, it subconsciously influenced me.

Vaclav might have been influenced by the elementary school of Josef Polášek that he attended in Kyjov.

VN: I discovered the architectural quality of the school much later. It was much more about the row house where I grew up. Although it was a classic catalog project from the 80s, my parents invited an architect from Zlin for the interior, and there I sensed a significant shift compared to what the neighbors lived in.

Was there someone who led you to architecture?

VN: I lived under the impression that it is a prestigious and sought-after profession. That's why I chose it.

JS: Through art clubs in the people's art school. The hesitation between landscape and classical architecture was resolved only by the preparatory courses organized by the Czech Technical University in the southern Bohemian Lásenice. Among the participants, I was the only one who wanted to go into landscape architecture. Eventually, I was swept up by the crowd, but in hindsight, I have to admit that I was unacquainted with architecture and didn't even know that we had such a gem in Brno as the Tugendhat Villa.

VN: A neighbor in Kyjov who was an architect in a construction company paid a lot of attention to me in high school. He took me to Brno, where he showed me local buildings and introduced me to the Tugendhat Villa.

Did you try entrance exams for Brno or elsewhere after high school?

VN: Prague and Brno. At that time, the Ostrava Department of Architecture did not yet exist.

JS: Prague, Brno, and Liberec, but I didn’t even pass the first round of the talent exams with my homeworks, where they expected unbridled talent while I sent them labored perspectives. Eventually, I got into the remaining two, and influenced by the preparatory course, I enrolled in Prague without having any idea of what to expect. Unlike Vašek, I studied for a long time and at different schools.

So you both graduated from the FA VUT.

VN: We both met in the same group as freshmen, but Honza had already spent two years in Prague and Ostrava.

JS: At that time, I was searching for myself and considering whether architecture would be the right path. The studios I wanted were unavailable to freshmen. At the same time, I received a draft notice for the army. So I switched to the Ostrava building school. There, a friend persuaded me to try talent exams for Brno again, where I met Vašek in the same group.

What did this school give you?

JS: At the beginning, we caught a good wave, where the basics of design were taught by Bára Ponešová and Radek Suchánek. Workshops were held at Oldřich Rujbr's cottage. There was an enormous sense of enthusiasm and energy.

An interesting wave at the Brno school could also have been at the beginning of the 90s when Ivan Ruller invited Miroslav Masák or Alena Šrámková to lead diploma projects as the dean.

VN: In our time, teachers like Zdeněk Fránek or Petr Hurník taught there, who later went to Liberec or even Ostrava. We experienced our studies not only as students attending all lectures and exercises but also as teachers led by Josef Chybík.

JS: Petr Hurník energetically led urban design studios, Karel Doležel organized unforgettable excursions.

VN: We spent the most time in the studio, where we learned from each other. In the fifth year, an internship was mandatory where everyone could go wherever they wanted.

Honza then decided to travel to America.

JS: In my fourth year, I completed an Erasmus internship at the University of Brighton while simultaneously working on my bachelor's thesis, which I later defended in Brno. England opened new horizons for me. In comparison to us, they didn’t delve deeply into technical subjects, but the students dealt with phenomenological themes and were not afraid of visionary concepts. Erasmus also gave me self-confidence, so I decided to do my mandatory internship in an English-speaking country. I printed dozens of small portfolios and sent them by regular mail because I knew that email applications ended up with secretaries and often never reached the main architects.

What was the main impulse for your trip to America?

JS: The initial impulse was Karel Doležel, who organized an excursion to Zlin to the Twenty-One, during the bus ride he read to us in Slovak Karfík's memories, who also traveled to America and wanted to develop these experiences in the Czechoslovak environment upon his return.

At school, I stated that there are no small goals, and we must go work with Jiřičná or Kaplický. When else to take a bold step but now. I did not want to stay in Brno or move a hundred kilometers to Vienna.

I worked at RoTo Architects with Michael Rotondi. I supplemented my work in the studio with visits to lectures at the Sci-ARC university. Due to the financial crisis, after six months, they informed me that I could work for them for free, so I found the ZH-architects studio in Manhattan, where I spent another six months.

Vašek completed an internship in the Netherlands.

VN: The Netherlands opened my eyes. In terms of higher cultural awareness, greater demand for our services, and more time to solve the task. On the internet, I was captivated by the Booster pumping station from the Amsterdam studio Group A. I sent my portfolio to many addresses, but they were the first to respond, and in hindsight, I realize it was the best choice. I walked to work surrounded by iconic buildings that I knew from lectures by Karel Doležel on contemporary architecture. It was a great school where I learned from real examples.

How was it possible to work during your master's studies?

VN: During my studies, I worked for a while for Velkovi, but I had to leave because I couldn't keep up with school.

JS: Vašek was a better student. I, on the other hand, gained more experience outside of school. I collaborated with Radek Hála, where I was not just in the position of a draftsman but also went to construction sites and meetings with clients.

How did the first steps after school go? When did you decide to establish a joint studio?

VN: I received my diploma after a formal six-year study in 2009, when a financial crisis fully erupted in the Czech Republic. All studios downsized their teams. I sent out a lot of portfolios, but I mainly wanted to work with Eva Jiřičná in Prague. Meanwhile, I received a call from Lábus's studio that a position had opened up. I immediately interrupted my vacation, jumped on a train, and went for an interview with a backpack. At Lábus's studio, there was a familial atmosphere. The biggest asset was the stability of a studio of six people. My current wife had also just started an Erasmus internship in Vienna, so I traveled there regularly to visit her, but it was still a long distance from Prague. As soon as she finished school, she stayed in Vienna to work, which was an impulse for me to leave Prague and move closer to my love. Honza and I had already completed our first joint project - interventions for Urban Interventions Brno. At that time, I was still working for Lábus, and the project was created in the evenings. It was the reconstruction of JAMU dormitories in Malinovského náměstí by Zdeněk Makovský.

JS: We felt that other projects were taken too seriously. We approached the playful way and simultaneously expressed ourselves to a place that irritated us. Primarily it was the emptiness between the historical and modern façades.

VN: We both completed several school studios with Makovský; I did my diploma with him, so we wanted to react to him in a fun way, and we suggested a slide.

JS: The historical façade lacks windows, and only empty openings remain through which we shoved a slide, and while riding, people would find themselves outside and inside the building. Our project aimed to highlight this peculiar backdrop with turrets and the unknown postmodern position of Zdeněk Makovský.

VN: I worked in Lábus's Prague studio for three years, and then I moved to Brno so I could spend every other weekend with my current wife in Vienna. The Austrian capital is an excellent textbook of architecture.

Many Brno graduates also end up in Viennese studios, but you decided to stand on your own feet in Brno. How difficult was that?

VN: Before our projects took off, I still worked for Petr Hrůša for another three-quarters of a year after moving to Brno, where I participated in the project of the castle riding school in Valtice.

JS: It took a lot of courage to start our studio and have an idea of financial security. I initially also worked at DRNH.

What was your first contract that gave you the impetus to become independent and establish SENAA?

VN: Our first investors purchased a small manor house in Milonice near Bučovice, for which we conducted measurements and redrawing. Occasionally someone would call us expressing a desire to use our services, so we started looking for an office where we could operate. Initially, we shared a small ground-floor space with a storefront along with Veronika Dobešová from Magion and Daniela Hanousková Boučková. It was on Tyršova Street at the Slovanský Square. Every morning we started a ritual where we first had to chop wood and heat the stove. After the office was reconstructed, we ran out of money and work. We picked up the phone and started calling clients until one investor appeared, who bought an apartment in a new building and initially only wanted to consult about the placement of a bathtub in the bathroom, but in the end, we proposed a complete interior.

JS: The client had a diving school, was interested in the underwater world, and loved working with stone in Egyptian hotels, which they wanted to carry over into their own home, which has a beautiful view of the Brno dam. Initially, they also wanted a large aquarium, which we replaced with large backlit onyx panels.

Fairly early on, you began with large development projects.

VN: That's just an illusion. At that time, we were still sitting on multiple chairs. I did visualizations for Velkových studio while Honza partially worked for Hála. We still didn't know if we could sustain ourselves.

VN: My dad was the principal of the elementary school in Kyjov, which was merging with another school at the time, and we were designing a cabin's equipment for them. After this period of uncertainty, suddenly three contracts coincided. Honza's classmate asked us for a family house project in Víceměřice, for a friend we designed a family house in Násedlovice, and a pair of developers, one of whom was my friend's husband, commissioned us for a residential complex in Újezd near Průhonice.

JS: So we followed the classic route of 3xF. Besides family and friends, dreamers who wanted to build organic houses from old tires in the hillside approached us, but it ultimately didn’t work out.

VN: The first three family house projects turned out great.

JS: In that development, it also started with a timid design of a twin house, but later expanded into a whole urban design of two three-family houses and one twin house. It was structured in phases, so it could be relatively easily financed and successfully completed. By the way, we still collaborate with these clients today.

JS: Gradually, more commissions came, so we no longer had to worry about our existence.

VN: We met another significant client during a vacation with my wife's friends. The owner of a glass factory from Poděbrady commissioned us to renovate a functionalist villa. She was satisfied with the result, and we still work for her. We designed directly for the factory, stands for exhibitions, or also a recreational cottage in Kořenov in the Jizera Mountains.

JS: We operate in the environment of hardworking people who are successful in their profession. They approach us when they want help in improving their business or their own living space. Subsequently, they recommend us to their extended family, acquaintances, and projects gradually accumulate.

You graduated and are based in Brno, but you don't get many opportunities to build here.

VN: Which is true, but now it is starting to change. We received a commission for the reconstruction of a villa in the Masaryk Quarter, where together with Eva Wagner, we are completing the garden. Neither of us comes directly from Brno, so we had to gradually build local ties.

JS: At first, we naively believed that if we had a ground-floor studio with 'Architects' written in the window, clients would call us themselves, but the first contracts came from Prague, Poděbrady, or southern Moravia and had nothing to do with the office's location.

VN: From Lábus's studio, we were used to a high standard of documentation processing and details. The first commission for the house in Víceměřice was full of ideas that construction firms weren’t capable of realizing for a long time.

Your work features quality materials and craftsmanship, which is initially more expensive but pays off in a longer perspective, both through beautiful aging and lower maintenance demands.

JS: At school in Brighton, material theory is taught. We analyzed texts, visited buildings, and discussed reasons and appropriateness of usage on site. Vašek absorbed this while at Lábus's, where they worked with natural stucco.

VN: Those are things you won’t be told in school. It’s not easy to learn either. It's a process of years of gathering experience. Even after a year of working at Lábus's studio, I still felt like a blank sheet of paper. I spent a lot of extra time in a great team; they passed on a lot of experience to me, and only then did I form my opinion on architecture.

JS: Only in retrospect did I realize that they told us what is great or bad in school, but they did not elaborate on why that building is good.

VN: As an example, I take Rozehnal's children's hospital in Černá Pole, which is usually shown only in one photograph from Milady Horákové Street. At school, we were instilled with how great that building is, but I had always thought it was because of the dynamic bending of the façade onto the street. I only knew the building from photographs and we never went to see it. Now, when we have a one-year-old child, we go there for regular check-ups with doctors, and now I understand the brilliance of the design that lies primarily in the great operation and spatial solution of the hospital.

The hospital is like a small city, whose operation can only be handled by a mature architect.

VN: These things can only be understood over time and cannot be passed on within a few years at school. Three years of intensive work at Lábus's helped accelerate this developmental maturation and subsequently embark on independent design.

JS: While Lábus's work, where Vašek learned the craft, is consistent, in the studio DRNH, where I worked, it was based on greater playfulness and diversity.

VN: For the family house in Víceměřice, we drew details at 1:5, 1:2, and 1:1, but later we found that the bricklayers couldn't realize or even read them. They built according to basic floor plans without even looking at the schedules.

Does this mean you had to be constantly on site and watch over everything?

JS: We were rather searching for ourselves. We already knew how it worked in established offices, where the quality standard is set long-term, and we wanted to transfer that into our own practice, which doesn't happen immediately and you deal with the degree of compromise. In America, construction was viewed primarily from the outside, which I couldn't identify with.

Especially in Los Angeles, there is a tendency to create façades.

JS: These were impressive concepts and forms, but I always tried to present a usable inner space to people. Gehl’s book centers around the socio-economic space of the street, square, and park. Subconsciously, I have in mind Tugendhat or Müller Villa, where it is also primarily about the internal organization of the house. This has been important from the beginning for our studio. We try to enrich spaces with internal views or opening into the gallery. Then, one can slightly compromise on details or choose cheaper materials because the strength of the concept has already been spatially defined.

VN: The object must be beautiful even in rough construction. Then cosmetic crutches won't help. Ultimately, it can happen that there won't be enough funding for them, and the house will end up ugly. We always approach that it must be built cheaply from white plaster and must be beautiful in its simplicity.

JS: In proportions, spatial connections, and sizes of openings. At the same time, we intertwine it with materiality, partial coverings, and structure of plasters.

VN: Earlier, we searched for a concept from inside out and vice versa, but then we realized that we must first correctly position the chimney.

Which has archetypal connotations and literally guarantees warmth at home.

VN: An impressively positioned fireplace in the living space can cause issues with the flue in the upper floor. We had to absorb all the technical aspects of the building.

JS: In design, theory and technique intertwine. We don't want to be mere designers. We had to learn to technically review the design well without compromising the original idea, ensuring the result wasn’t just mere construction.

You create outside of big cities. How do you manage to promote quality modern architecture in these areas?

JS: At first, we had three family houses in Násedlovice, Víceměřice, and Valtice. We felt that we didn't want to enter the rural environment with an aggressive mass. It was an important stage in the development of our family house typology with a gable roof. We maintained a lapidary expression to the street, but at the same time offered a lightening of the mass with corner windows or pushed the façade back using a bay window. We come with a high standard of details or frameless glazing, which people in the local environment were not used to, but nonetheless, raised living comfort. Inside, the houses offer rich spatial play and in some cases also above-standard equipment such as a wine cellar or sauna.

Everything harmoniously fits into the surroundings.

JS: We went against the desire of young architects to create aggressive cubes or dramatic cantilevers. For a long time, we asked ourselves how to keep a gable-roofed house in good proportions.

Did any of your school projects have a gable roof?

VN: No.

JS: Never.

When did the first gable roof appear then?

VN: Only with these three family houses for friends when we started grappling with the reality of local authorities and regulations. There was no other way. We considered many variants, but according to the zoning plan, a flat roof could not be built in that location.

JS: One of the family houses replaced the original unsuitable building that had to be demolished, and in the original footprint, we proposed a new structure that was materially identical and adapted to the surroundings.

VN: With these three family houses, we began gathering our first experiences with gable roofs.

JS: We thought about every detail, and thanks to the client's collective desire for innovation, we succeeded in realizing the houses. The investor has a lot of room to influence the design. We don't want to choose the flooring substrates for them, select picture frames, or coordinate the color of slippers, as Loos joked about it.

VN: Modern doesn’t have to be just a box of exposed concrete but also a white-plastered house with a gable roof that fits seamlessly into the village context. There is a much greater likelihood it will suit additional future users than highly individualized modernism.

JS: We are keeping an eye on Zlin minimalists like Mudřík, Chládek, or Míček, and we cheer for their efforts to build on the tradition of Baťa architecture. So far, we haven't had the opportunity to build in this modernist city, but we are currently completing the reconstruction of a villa in Brno's Masaryk Quarter, which has an interwar functionalist spirit, so a flat roof makes sense there.

This trio of family homes with gable roofs you managed on your own at first, but then came a large commission for a residential complex in Újezd near Průhonice, where you had to invite additional collaborators.

VN: On most projects, Jan Gadziala participated, who has been with us almost from the beginning. We were won over by his perfect drawings and we still collaborate with him.

JS: Later, more assignments came in various locations with different façades and roof types, which helped defeat the idea that SENAA only designs rural houses with gable roofs. Now several family houses have emerged, which are all located on steep slopes. The villas in Olomučany and Řícmanice are situated on complex sites, which forces us to think in completely different, richer spatial considerations, address solar gains more carefully, and most often have flat roofs.

VN: The important thing for us is not the outdoor stunning effect, but rather a set of details, internal functions, and nooks that ultimately create a pleasant living environment.

JS: In the case of Müller Villa or Winternitz Villa by Adolf Loos, we love moments when you sit in the living room yet have an overview of the action in the dining room, can warm by the fireplace, and at the same time look outside. It is not a set of square rooms separated by doors; everything is continuously interconnected visually and aurally. This is difficult to explain to clients, which is why we often take them to various buildings or our previous realizations for them to experience it directly and gain their trust.

The dialogue with investors about the internal use is far more important to us than the external shaping of the house.

VN: Externally, houses may appear utilitarian or even banal, but internally they are incredibly well thought out for a long time and are always conceived in close cooperation with the load-bearing structure. We understand that the principle of architecture is not to keep coming up with something new. At school, we were taught that in order to become a great architect, one must come up with ever larger cantilevers. After our epiphany, we realized that it is primarily about a collection of small things that make architecture user-friendly.

This wave is being followed by Chinese cities or the Persian Gulf area, where one feels like being in an amusement park. In contrast, Switzerland or Belgium takes a calm path of normalcy over the long term.

JS: We don’t have such a clearly defined goal. In some larger typologies like a church or gallery, spatial generosity is desirable. Some studios limit themselves with their production, unable to surpass their own shadow, and create large houses, which we fortunately managed to do. At the same time we were designing family houses, we were approached for a showroom in Čejč, which will be the flagship of a company producing stainless steel ovens.

I remember your premises on Kopečná Street with a window to the street. Where else have you been based?

JS: Before that, we shared a space near Slovanský Square with other young female architects, and from Kopečná Street, we moved to our current office on Jakubské náměstí.

VN: The beginnings were romantic with wood stoves, on which we also brewed coffee and prepared shared lunches, after which came a siesta, but with the first employees, we had to set an example, and the vacation mode ended.

You mentioned the wood stove that heated your first studio. The fireplace also appears in many of your designs. How important an element is it for you?

VN: In Lábus's studio, the theme of the fireplace in the center of the layout plays an important role. We initially advocated this element as well, but during cooperation with Prague investors, we realized that the theme is not so sought after. After all, we are boys from the village where everyone had a garden behind their house. A city person functions differently; they don't want to take care of their own flowerbeds or chop wood for the fireplace. What seems romantic ultimately requires effort and can never be completely tidy.

JS: The wood typically used for heating in the village is definitely not meant to be showcased indoors.

VN: And if it is, it would be labor intensive and would not justify the end effect.

JS: We tend to advise clients against installing a fireplace in the city. In discussions, we delve into the smallest details. We talk to clients about whether they are right- or left-handed, and we adjust the most efficient operation accordingly, including appliances. Architects are often assigned the role of designers who do not understand practical matters, which we disagree with. We are very practical ourselves and try to seek clients on a similar wavelength.

Where do your projects come from? Do you initiate them through dialogue with the public administration or approach private investors, or do you wait for someone to contact you?

VN: We thought for a long time about how to attract potential clients and make ourselves known to the public.

After the first projects for former classmates and family members, their acquaintances began to reach out to us.

JS: Our plumber calls it the snowball effect, where additional projects start rolling in by themselves. That snowball has been rolling for ten years. We are still approached by new clients, and just as the snowball grows, so does the volume of commissions.

VN: Very soon, completely unknown people began to contact us who found us on the internet.

It is necessary to venture outside your professional bubble and present your work in lifestyle magazines, which tend to have a broader reach and unlike specialist magazines can be found at ordinary kiosks.

JS: We didn't want to be pigeonholed in the category of interiors or family houses, so we did not rush into such magazines. Most clients want what they’ve already seen somewhere. Based on references from family houses, no one assigns us an apartment building or sports complex. Moreover, the paths to projects are completely unpredictable. For example, from one minor interior project, we got the realization of a family house for fifteen million. Many of today's architects have become enamored with a clean minimalist expression of their buildings, which has no chance of appealing to a broad part of clients. Fortunately, contemporary architecture has many faces. We remain open and enjoy discussing architecture with our collaborating professions, where for example our traffic specialists invited us to a project on modular parking houses and systems from mmcité, which indirectly led us to railway stops or parking garages.

VN: When the magazine Interior published modifications of one of our apartments, at least ten interested parties reached out, wanting to order exactly the same from us.

JS: The interior is an integral part of each of our designs. We consider it an essential part of the project. We just don’t want to end up in the position of exterior skin designers or apartment designers.

How did you get to projects for the public sector, which have the potential to reach a much wider audience than a private family house?

VN: A young ambitious mayor from Terezín in southern Moravia found us on the web and contacted us, stating that he needed to build a small morgue of 3x3m at the cemetery. Then came additional smaller tasks such as sidewalks in the cemetery and gradually the scope grew from a winery museum to the renovation of a cultural house.

You became the main municipal architects, after all.

JS: If we were to recite contracts saying they are too small, then we would never get to work. Initially, we were not even profitable, but we sensed that we were doing something good for the right people, which was confirmed over time. After completion, we saw how people used the sports complex we designed and were satisfied, which was a significant asset for the future.

VN: Speaking of acquiring projects, a story about Bjarke Ingels comes to mind, where he couldn’t find his partner for tennis, which also happened to someone on the next court, and aside from playing a few sets, he gained an investor for several residential complexes in Copenhagen. Similarly, I went on a vacation with cyclists, among whom was the owner of a glass factory, whom we helped solve one renovation, and since then, she regularly approaches us with additional commissions.

Currently, your office has around ten employees, which allows you to work on large commissions like the covered swimming pool in Kyjov.

JS: After private clients, larger companies began to approach us. Most likely, we wouldn’t manage to work on three multifunctional buildings simultaneously at the level of executive projects. The design of houses and studio projects is still manageable by two people. However, we want to maintain control over all design phases, consult continuously, present to all committees, obtain authority statements, and see them through to realization. Realization is the art of compromise.

So you consider the current size to be ideal for keeping track of everything that is happening?

VN: We entrust larger projects to more experienced architects in our office. We have a hierarchy set up, but everyone has the opportunity to express their opinion. Even an intern can have a great idea, and we don't exclude the possibility that it will be reflected in the project and subsequent realization. We assign small contracts to students to design them themselves and go through all the phases. This way, they take ownership of the project. We don't want interns in the position of mere redrawers of our sketches.

JS: On the other hand, however, we know every project down to the last detail. We don’t want to end up in a situation where we’re sitting at home while a group of strangers under our brand designs houses.

Your first joint project was for Urban Interventions, which was in some way a charitable manifesto. Did you later participate in similar actions? Do you participate in architectural competitions?

JS: We attend invited competitions, where they cover our entry costs.

VN: We always had so much work that there was no need to strive for additional forms of competition. We want to finish work sensibly, operate under normal conditions, and not work at nights.

JS: We don’t know exactly how it happened, but we have been approached by major development companies like Trikaya or Crestyl, so we are getting interesting commissions.

VN: We have entered the consultation of public spaces and railway stops through the traffic-engineering association Laboro. In this transport world, there are many restrictions and interests, where the architect has very few options, but we still strive to improve these spaces. It’s like a state within a state with a heap of regulations, where everyone expresses their opinion on the project, but no one can make a firm decision, even though it’s a small contract.

You have entered the forbidden world previously accessible only to staticians and engineers. Roman Koucký similarly paved the way for architects to design bridges.

JS: We are not afraid of any contracts or typologies. When we are invited to propose a stop or something we have not done before, we quickly study everything accordingly.

We do not aim solely for ever larger construction scales, but now we have been approached by the owner of an office furniture factory and we are designing a modular furniture series A Look, which we presented at Mobitex and received third prize. In the factory, we developed prototypes, addressing production opportunities on-site. Unlike public administration, everything proceeded quickly and flexibly.

VN: We started designing furniture just before the outbreak of the coronavirus, after which all offices closed, and people moved to home offices, which will most likely also reflect in the future typology of administrative buildings.

Humans are social creatures, so people will want to return to offices. The delay in the project at least gives more time to think everything over.

VN: Architecture is a slow process. Now we are starting to build what we designed six years ago.

Koolhaas claims he manages to realize one project out of ten. How is it with you?

VN: At least half, but rather two-thirds of the projects eventually get built. Koolhaas and similar architects are visionaries who build unusual things where the outcome is not clear in advance, and in the end, neither is the client satisfied.

JS: These architects have a sculptural approach based on external astonishment, which is precisely the opposite of us.

VN: Their architecture seeks attention, revives spaces, and can diverge from the usual production. Alongside these stars are ordinary houses that shape the urban structure, and it definitely cannot be said that they are worse. Our practice is based on rationality and client satisfaction.

VN: People intuitively do not want to spend time in an ugly environment. However, the general idea of what is beautiful differs. Every good building initiates the emergence of other beautiful buildings in its vicinity.

JS: We have no problem praising good work by colleagues and sincerely wish that more realizations by other studios grow in the same place. We all want to improve the environment in which we live. There’s no disgraceful theme, only disgraceful results. Some would like to design only churches or galleries, but we spend more time in shopping centers, so our efforts to improve should be directed in this direction.

VN: Our architecture is not an 'eyecatcher' that programmatically attracts attention, but rather about higher quality execution and satisfying use. We create a good environment where the SENAA label won’t always be in sight.

It’s necessary to know when to stop in order to prevent a deviation from pompousness into a position of excessive asceticism.

VN: We certainly do not choose the cheapest materials and admit that our buildings are relatively expensive to execute. There is a big difference between furniture made from pallets that screams cheapness from afar. We invest in materials and details so that everything ends up looking ordinary.

JS: My grandfather used to say that it’s beautiful to watch figure skating, where all movements are synchronized, muscles are properly engaged, and the outcome appears very natural, light, and effortless. But years of hard work and maximum concentration on the result hide behind it.

Do you have any dream projects or do you sketch into a drawer?

VN: Now our dream is for the swimming pool in Kyjov to be successfully completed. We believe that this could lead to other public buildings. A school, church, or museum are the highest we can aspire to as architects because that touches a wide spectrum of people.

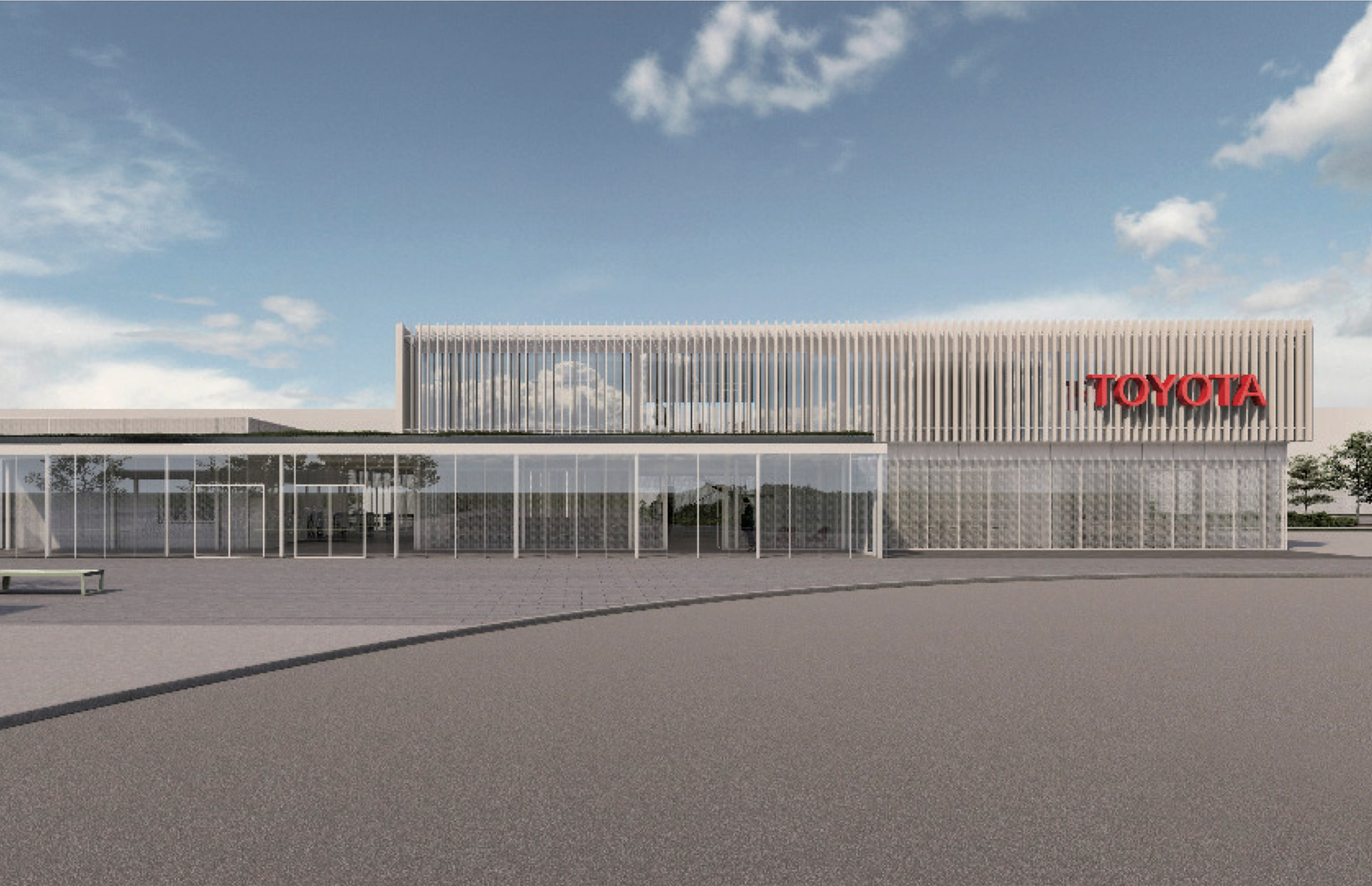

JS: For example, we were invited to participate in a competition for the redevelopment of the Research Institute of Building Materials on Kaštanová Street in Brno, where there is a plan to build an administrative center with LEED certifications and sustainable methods of design within fifteen years. The automotive company Toyota approached us with a commission for the main entrance building, including a recruitment and training center in Kolín. New real projects keep appearing, so we no longer have time to sketch visions into a drawer.

JS: Recently, in addition to public administration and large enterprises, young investors have started to contact us who realize there are more lasting values than just quick profits.

VN: Previously, they actively traded stocks, and at a certain age, they began to consider what tangible and valuable will remain after them.

JS: Referring to the Brno example of Kaštanová, investors do not wish for just another office complex, but think about the carbon footprint left behind. Prague developers no longer just want to build and sell quickly, but realize the added value of architecture and cultivate the environment, which is great news for our profession.

Interviews with both architects took place on May 17, June 1, and June 15, 2021, in the Brno studio SENAA at Jakubské náměstí.

VN: Probably already in elementary school when I was gluing paper models from the ABC magazine prepared by architect Richard Vyškovský. I eagerly glued from small cottages and houses to an entire urban heritage reservation.

JS: I was similar and as a child, I glued airplane models. I got into architecture one generation through my grandfather who loved Gocárovy buildings, photographed them, filmed them, and wrote film scripts about them. In the 60s, together with the Hanak architect Pavlovský, he reconstructed a homestead in a village near Prostějov. When designing, they were freely inspired by F.L.Wright. They used stone walls, beam ceilings, and large windows. People in the surrounding area thought they were building some kind of store. I spent my vacations in this building, and even then, it subconsciously influenced me.

Vaclav might have been influenced by the elementary school of Josef Polášek that he attended in Kyjov.

VN: I discovered the architectural quality of the school much later. It was much more about the row house where I grew up. Although it was a classic catalog project from the 80s, my parents invited an architect from Zlin for the interior, and there I sensed a significant shift compared to what the neighbors lived in.

|

| Complete composition of the SENAA architects team in 2021. |

Was there someone who led you to architecture?

VN: I lived under the impression that it is a prestigious and sought-after profession. That's why I chose it.

JS: Through art clubs in the people's art school. The hesitation between landscape and classical architecture was resolved only by the preparatory courses organized by the Czech Technical University in the southern Bohemian Lásenice. Among the participants, I was the only one who wanted to go into landscape architecture. Eventually, I was swept up by the crowd, but in hindsight, I have to admit that I was unacquainted with architecture and didn't even know that we had such a gem in Brno as the Tugendhat Villa.

VN: A neighbor in Kyjov who was an architect in a construction company paid a lot of attention to me in high school. He took me to Brno, where he showed me local buildings and introduced me to the Tugendhat Villa.

Did you try entrance exams for Brno or elsewhere after high school?

VN: Prague and Brno. At that time, the Ostrava Department of Architecture did not yet exist.

JS: Prague, Brno, and Liberec, but I didn’t even pass the first round of the talent exams with my homeworks, where they expected unbridled talent while I sent them labored perspectives. Eventually, I got into the remaining two, and influenced by the preparatory course, I enrolled in Prague without having any idea of what to expect. Unlike Vašek, I studied for a long time and at different schools.

|

| Urban interventions Brno 2011 |

So you both graduated from the FA VUT.

VN: We both met in the same group as freshmen, but Honza had already spent two years in Prague and Ostrava.

JS: At that time, I was searching for myself and considering whether architecture would be the right path. The studios I wanted were unavailable to freshmen. At the same time, I received a draft notice for the army. So I switched to the Ostrava building school. There, a friend persuaded me to try talent exams for Brno again, where I met Vašek in the same group.

What did this school give you?

JS: At the beginning, we caught a good wave, where the basics of design were taught by Bára Ponešová and Radek Suchánek. Workshops were held at Oldřich Rujbr's cottage. There was an enormous sense of enthusiasm and energy.

An interesting wave at the Brno school could also have been at the beginning of the 90s when Ivan Ruller invited Miroslav Masák or Alena Šrámková to lead diploma projects as the dean.

VN: In our time, teachers like Zdeněk Fránek or Petr Hurník taught there, who later went to Liberec or even Ostrava. We experienced our studies not only as students attending all lectures and exercises but also as teachers led by Josef Chybík.

JS: Petr Hurník energetically led urban design studios, Karel Doležel organized unforgettable excursions.

VN: We spent the most time in the studio, where we learned from each other. In the fifth year, an internship was mandatory where everyone could go wherever they wanted.

|

| Reconstruction of a house in the center of Brno |

Honza then decided to travel to America.

JS: In my fourth year, I completed an Erasmus internship at the University of Brighton while simultaneously working on my bachelor's thesis, which I later defended in Brno. England opened new horizons for me. In comparison to us, they didn’t delve deeply into technical subjects, but the students dealt with phenomenological themes and were not afraid of visionary concepts. Erasmus also gave me self-confidence, so I decided to do my mandatory internship in an English-speaking country. I printed dozens of small portfolios and sent them by regular mail because I knew that email applications ended up with secretaries and often never reached the main architects.

What was the main impulse for your trip to America?

JS: The initial impulse was Karel Doležel, who organized an excursion to Zlin to the Twenty-One, during the bus ride he read to us in Slovak Karfík's memories, who also traveled to America and wanted to develop these experiences in the Czechoslovak environment upon his return.

At school, I stated that there are no small goals, and we must go work with Jiřičná or Kaplický. When else to take a bold step but now. I did not want to stay in Brno or move a hundred kilometers to Vienna.

I worked at RoTo Architects with Michael Rotondi. I supplemented my work in the studio with visits to lectures at the Sci-ARC university. Due to the financial crisis, after six months, they informed me that I could work for them for free, so I found the ZH-architects studio in Manhattan, where I spent another six months.

|

| Residential building in the center of Uherské Hradiště |

Vašek completed an internship in the Netherlands.

VN: The Netherlands opened my eyes. In terms of higher cultural awareness, greater demand for our services, and more time to solve the task. On the internet, I was captivated by the Booster pumping station from the Amsterdam studio Group A. I sent my portfolio to many addresses, but they were the first to respond, and in hindsight, I realize it was the best choice. I walked to work surrounded by iconic buildings that I knew from lectures by Karel Doležel on contemporary architecture. It was a great school where I learned from real examples.

How was it possible to work during your master's studies?

VN: During my studies, I worked for a while for Velkovi, but I had to leave because I couldn't keep up with school.

JS: Vašek was a better student. I, on the other hand, gained more experience outside of school. I collaborated with Radek Hála, where I was not just in the position of a draftsman but also went to construction sites and meetings with clients.

|

| Reconstruction of a South Bohemian homestead |

How did the first steps after school go? When did you decide to establish a joint studio?

VN: I received my diploma after a formal six-year study in 2009, when a financial crisis fully erupted in the Czech Republic. All studios downsized their teams. I sent out a lot of portfolios, but I mainly wanted to work with Eva Jiřičná in Prague. Meanwhile, I received a call from Lábus's studio that a position had opened up. I immediately interrupted my vacation, jumped on a train, and went for an interview with a backpack. At Lábus's studio, there was a familial atmosphere. The biggest asset was the stability of a studio of six people. My current wife had also just started an Erasmus internship in Vienna, so I traveled there regularly to visit her, but it was still a long distance from Prague. As soon as she finished school, she stayed in Vienna to work, which was an impulse for me to leave Prague and move closer to my love. Honza and I had already completed our first joint project - interventions for Urban Interventions Brno. At that time, I was still working for Lábus, and the project was created in the evenings. It was the reconstruction of JAMU dormitories in Malinovského náměstí by Zdeněk Makovský.

JS: We felt that other projects were taken too seriously. We approached the playful way and simultaneously expressed ourselves to a place that irritated us. Primarily it was the emptiness between the historical and modern façades.

VN: We both completed several school studios with Makovský; I did my diploma with him, so we wanted to react to him in a fun way, and we suggested a slide.

JS: The historical façade lacks windows, and only empty openings remain through which we shoved a slide, and while riding, people would find themselves outside and inside the building. Our project aimed to highlight this peculiar backdrop with turrets and the unknown postmodern position of Zdeněk Makovský.

VN: I worked in Lábus's Prague studio for three years, and then I moved to Brno so I could spend every other weekend with my current wife in Vienna. The Austrian capital is an excellent textbook of architecture.

|

| Entrance building of the Toyota car plant |

Many Brno graduates also end up in Viennese studios, but you decided to stand on your own feet in Brno. How difficult was that?

VN: Before our projects took off, I still worked for Petr Hrůša for another three-quarters of a year after moving to Brno, where I participated in the project of the castle riding school in Valtice.

JS: It took a lot of courage to start our studio and have an idea of financial security. I initially also worked at DRNH.

What was your first contract that gave you the impetus to become independent and establish SENAA?

VN: Our first investors purchased a small manor house in Milonice near Bučovice, for which we conducted measurements and redrawing. Occasionally someone would call us expressing a desire to use our services, so we started looking for an office where we could operate. Initially, we shared a small ground-floor space with a storefront along with Veronika Dobešová from Magion and Daniela Hanousková Boučková. It was on Tyršova Street at the Slovanský Square. Every morning we started a ritual where we first had to chop wood and heat the stove. After the office was reconstructed, we ran out of money and work. We picked up the phone and started calling clients until one investor appeared, who bought an apartment in a new building and initially only wanted to consult about the placement of a bathtub in the bathroom, but in the end, we proposed a complete interior.

JS: The client had a diving school, was interested in the underwater world, and loved working with stone in Egyptian hotels, which they wanted to carry over into their own home, which has a beautiful view of the Brno dam. Initially, they also wanted a large aquarium, which we replaced with large backlit onyx panels.

|

| Interior of a house in Lovčice |

Fairly early on, you began with large development projects.

VN: That's just an illusion. At that time, we were still sitting on multiple chairs. I did visualizations for Velkových studio while Honza partially worked for Hála. We still didn't know if we could sustain ourselves.

VN: My dad was the principal of the elementary school in Kyjov, which was merging with another school at the time, and we were designing a cabin's equipment for them. After this period of uncertainty, suddenly three contracts coincided. Honza's classmate asked us for a family house project in Víceměřice, for a friend we designed a family house in Násedlovice, and a pair of developers, one of whom was my friend's husband, commissioned us for a residential complex in Újezd near Průhonice.

JS: So we followed the classic route of 3xF. Besides family and friends, dreamers who wanted to build organic houses from old tires in the hillside approached us, but it ultimately didn’t work out.

VN: The first three family house projects turned out great.

JS: In that development, it also started with a timid design of a twin house, but later expanded into a whole urban design of two three-family houses and one twin house. It was structured in phases, so it could be relatively easily financed and successfully completed. By the way, we still collaborate with these clients today.

JS: Gradually, more commissions came, so we no longer had to worry about our existence.

VN: We met another significant client during a vacation with my wife's friends. The owner of a glass factory from Poděbrady commissioned us to renovate a functionalist villa. She was satisfied with the result, and we still work for her. We designed directly for the factory, stands for exhibitions, or also a recreational cottage in Kořenov in the Jizera Mountains.

JS: We operate in the environment of hardworking people who are successful in their profession. They approach us when they want help in improving their business or their own living space. Subsequently, they recommend us to their extended family, acquaintances, and projects gradually accumulate.

|

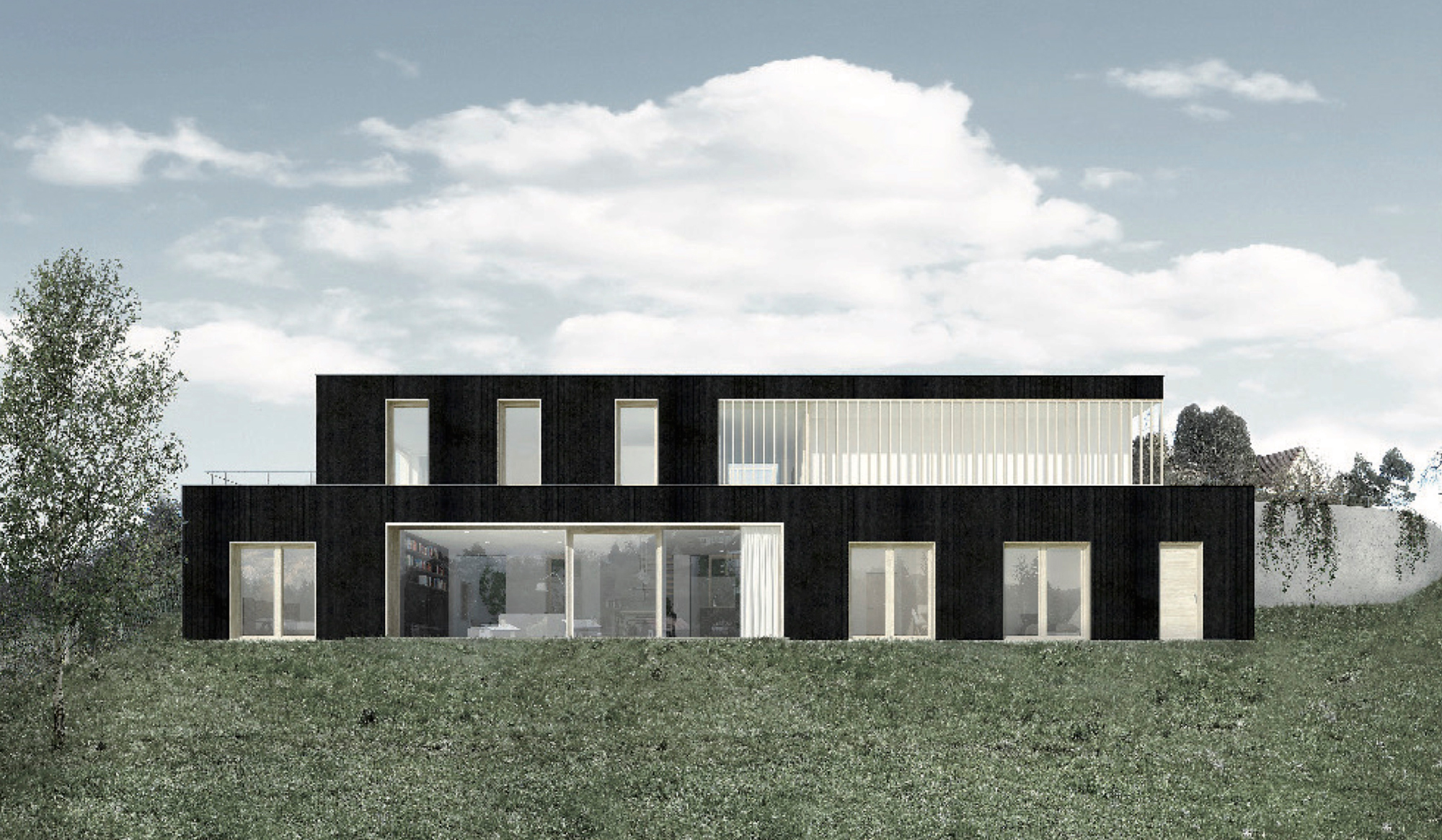

| Villa in Olomučany |

You graduated and are based in Brno, but you don't get many opportunities to build here.

VN: Which is true, but now it is starting to change. We received a commission for the reconstruction of a villa in the Masaryk Quarter, where together with Eva Wagner, we are completing the garden. Neither of us comes directly from Brno, so we had to gradually build local ties.

JS: At first, we naively believed that if we had a ground-floor studio with 'Architects' written in the window, clients would call us themselves, but the first contracts came from Prague, Poděbrady, or southern Moravia and had nothing to do with the office's location.

VN: From Lábus's studio, we were used to a high standard of documentation processing and details. The first commission for the house in Víceměřice was full of ideas that construction firms weren’t capable of realizing for a long time.

|

| House in Petrov |

Your work features quality materials and craftsmanship, which is initially more expensive but pays off in a longer perspective, both through beautiful aging and lower maintenance demands.

JS: At school in Brighton, material theory is taught. We analyzed texts, visited buildings, and discussed reasons and appropriateness of usage on site. Vašek absorbed this while at Lábus's, where they worked with natural stucco.

VN: Those are things you won’t be told in school. It’s not easy to learn either. It's a process of years of gathering experience. Even after a year of working at Lábus's studio, I still felt like a blank sheet of paper. I spent a lot of extra time in a great team; they passed on a lot of experience to me, and only then did I form my opinion on architecture.

JS: Only in retrospect did I realize that they told us what is great or bad in school, but they did not elaborate on why that building is good.

VN: As an example, I take Rozehnal's children's hospital in Černá Pole, which is usually shown only in one photograph from Milady Horákové Street. At school, we were instilled with how great that building is, but I had always thought it was because of the dynamic bending of the façade onto the street. I only knew the building from photographs and we never went to see it. Now, when we have a one-year-old child, we go there for regular check-ups with doctors, and now I understand the brilliance of the design that lies primarily in the great operation and spatial solution of the hospital.

|

| Apartment with onyx in Brno |

The hospital is like a small city, whose operation can only be handled by a mature architect.

VN: These things can only be understood over time and cannot be passed on within a few years at school. Three years of intensive work at Lábus's helped accelerate this developmental maturation and subsequently embark on independent design.

JS: While Lábus's work, where Vašek learned the craft, is consistent, in the studio DRNH, where I worked, it was based on greater playfulness and diversity.

VN: For the family house in Víceměřice, we drew details at 1:5, 1:2, and 1:1, but later we found that the bricklayers couldn't realize or even read them. They built according to basic floor plans without even looking at the schedules.

|

| Residential complex Újezd near Průhonice |

Does this mean you had to be constantly on site and watch over everything?

JS: We were rather searching for ourselves. We already knew how it worked in established offices, where the quality standard is set long-term, and we wanted to transfer that into our own practice, which doesn't happen immediately and you deal with the degree of compromise. In America, construction was viewed primarily from the outside, which I couldn't identify with.

Especially in Los Angeles, there is a tendency to create façades.

JS: These were impressive concepts and forms, but I always tried to present a usable inner space to people. Gehl’s book centers around the socio-economic space of the street, square, and park. Subconsciously, I have in mind Tugendhat or Müller Villa, where it is also primarily about the internal organization of the house. This has been important from the beginning for our studio. We try to enrich spaces with internal views or opening into the gallery. Then, one can slightly compromise on details or choose cheaper materials because the strength of the concept has already been spatially defined.

VN: The object must be beautiful even in rough construction. Then cosmetic crutches won't help. Ultimately, it can happen that there won't be enough funding for them, and the house will end up ugly. We always approach that it must be built cheaply from white plaster and must be beautiful in its simplicity.

JS: In proportions, spatial connections, and sizes of openings. At the same time, we intertwine it with materiality, partial coverings, and structure of plasters.

VN: Earlier, we searched for a concept from inside out and vice versa, but then we realized that we must first correctly position the chimney.

|

| Cottage in Kořenov |

Which has archetypal connotations and literally guarantees warmth at home.

VN: An impressively positioned fireplace in the living space can cause issues with the flue in the upper floor. We had to absorb all the technical aspects of the building.

JS: In design, theory and technique intertwine. We don't want to be mere designers. We had to learn to technically review the design well without compromising the original idea, ensuring the result wasn’t just mere construction.

You create outside of big cities. How do you manage to promote quality modern architecture in these areas?

JS: At first, we had three family houses in Násedlovice, Víceměřice, and Valtice. We felt that we didn't want to enter the rural environment with an aggressive mass. It was an important stage in the development of our family house typology with a gable roof. We maintained a lapidary expression to the street, but at the same time offered a lightening of the mass with corner windows or pushed the façade back using a bay window. We come with a high standard of details or frameless glazing, which people in the local environment were not used to, but nonetheless, raised living comfort. Inside, the houses offer rich spatial play and in some cases also above-standard equipment such as a wine cellar or sauna.

|

| Reconstruction of a villa in the Masaryk Quarter |

Everything harmoniously fits into the surroundings.

JS: We went against the desire of young architects to create aggressive cubes or dramatic cantilevers. For a long time, we asked ourselves how to keep a gable-roofed house in good proportions.

Did any of your school projects have a gable roof?

VN: No.

JS: Never.

When did the first gable roof appear then?

VN: Only with these three family houses for friends when we started grappling with the reality of local authorities and regulations. There was no other way. We considered many variants, but according to the zoning plan, a flat roof could not be built in that location.

JS: One of the family houses replaced the original unsuitable building that had to be demolished, and in the original footprint, we proposed a new structure that was materially identical and adapted to the surroundings.

VN: With these three family houses, we began gathering our first experiences with gable roofs.

JS: We thought about every detail, and thanks to the client's collective desire for innovation, we succeeded in realizing the houses. The investor has a lot of room to influence the design. We don't want to choose the flooring substrates for them, select picture frames, or coordinate the color of slippers, as Loos joked about it.

VN: Modern doesn’t have to be just a box of exposed concrete but also a white-plastered house with a gable roof that fits seamlessly into the village context. There is a much greater likelihood it will suit additional future users than highly individualized modernism.

JS: We are keeping an eye on Zlin minimalists like Mudřík, Chládek, or Míček, and we cheer for their efforts to build on the tradition of Baťa architecture. So far, we haven't had the opportunity to build in this modernist city, but we are currently completing the reconstruction of a villa in Brno's Masaryk Quarter, which has an interwar functionalist spirit, so a flat roof makes sense there.

|

| Villas in Divoká Šárka |

This trio of family homes with gable roofs you managed on your own at first, but then came a large commission for a residential complex in Újezd near Průhonice, where you had to invite additional collaborators.

VN: On most projects, Jan Gadziala participated, who has been with us almost from the beginning. We were won over by his perfect drawings and we still collaborate with him.

JS: Later, more assignments came in various locations with different façades and roof types, which helped defeat the idea that SENAA only designs rural houses with gable roofs. Now several family houses have emerged, which are all located on steep slopes. The villas in Olomučany and Řícmanice are situated on complex sites, which forces us to think in completely different, richer spatial considerations, address solar gains more carefully, and most often have flat roofs.

VN: The important thing for us is not the outdoor stunning effect, but rather a set of details, internal functions, and nooks that ultimately create a pleasant living environment.

JS: In the case of Müller Villa or Winternitz Villa by Adolf Loos, we love moments when you sit in the living room yet have an overview of the action in the dining room, can warm by the fireplace, and at the same time look outside. It is not a set of square rooms separated by doors; everything is continuously interconnected visually and aurally. This is difficult to explain to clients, which is why we often take them to various buildings or our previous realizations for them to experience it directly and gain their trust.

The dialogue with investors about the internal use is far more important to us than the external shaping of the house.

VN: Externally, houses may appear utilitarian or even banal, but internally they are incredibly well thought out for a long time and are always conceived in close cooperation with the load-bearing structure. We understand that the principle of architecture is not to keep coming up with something new. At school, we were taught that in order to become a great architect, one must come up with ever larger cantilevers. After our epiphany, we realized that it is primarily about a collection of small things that make architecture user-friendly.

This wave is being followed by Chinese cities or the Persian Gulf area, where one feels like being in an amusement park. In contrast, Switzerland or Belgium takes a calm path of normalcy over the long term.

JS: We don’t have such a clearly defined goal. In some larger typologies like a church or gallery, spatial generosity is desirable. Some studios limit themselves with their production, unable to surpass their own shadow, and create large houses, which we fortunately managed to do. At the same time we were designing family houses, we were approached for a showroom in Čejč, which will be the flagship of a company producing stainless steel ovens.

I remember your premises on Kopečná Street with a window to the street. Where else have you been based?

JS: Before that, we shared a space near Slovanský Square with other young female architects, and from Kopečná Street, we moved to our current office on Jakubské náměstí.

VN: The beginnings were romantic with wood stoves, on which we also brewed coffee and prepared shared lunches, after which came a siesta, but with the first employees, we had to set an example, and the vacation mode ended.

You mentioned the wood stove that heated your first studio. The fireplace also appears in many of your designs. How important an element is it for you?

VN: In Lábus's studio, the theme of the fireplace in the center of the layout plays an important role. We initially advocated this element as well, but during cooperation with Prague investors, we realized that the theme is not so sought after. After all, we are boys from the village where everyone had a garden behind their house. A city person functions differently; they don't want to take care of their own flowerbeds or chop wood for the fireplace. What seems romantic ultimately requires effort and can never be completely tidy.

JS: The wood typically used for heating in the village is definitely not meant to be showcased indoors.

VN: And if it is, it would be labor intensive and would not justify the end effect.

JS: We tend to advise clients against installing a fireplace in the city. In discussions, we delve into the smallest details. We talk to clients about whether they are right- or left-handed, and we adjust the most efficient operation accordingly, including appliances. Architects are often assigned the role of designers who do not understand practical matters, which we disagree with. We are very practical ourselves and try to seek clients on a similar wavelength.

Where do your projects come from? Do you initiate them through dialogue with the public administration or approach private investors, or do you wait for someone to contact you?

VN: We thought for a long time about how to attract potential clients and make ourselves known to the public.

After the first projects for former classmates and family members, their acquaintances began to reach out to us.

JS: Our plumber calls it the snowball effect, where additional projects start rolling in by themselves. That snowball has been rolling for ten years. We are still approached by new clients, and just as the snowball grows, so does the volume of commissions.

VN: Very soon, completely unknown people began to contact us who found us on the internet.

It is necessary to venture outside your professional bubble and present your work in lifestyle magazines, which tend to have a broader reach and unlike specialist magazines can be found at ordinary kiosks.

JS: We didn't want to be pigeonholed in the category of interiors or family houses, so we did not rush into such magazines. Most clients want what they’ve already seen somewhere. Based on references from family houses, no one assigns us an apartment building or sports complex. Moreover, the paths to projects are completely unpredictable. For example, from one minor interior project, we got the realization of a family house for fifteen million. Many of today's architects have become enamored with a clean minimalist expression of their buildings, which has no chance of appealing to a broad part of clients. Fortunately, contemporary architecture has many faces. We remain open and enjoy discussing architecture with our collaborating professions, where for example our traffic specialists invited us to a project on modular parking houses and systems from mmcité, which indirectly led us to railway stops or parking garages.

VN: When the magazine Interior published modifications of one of our apartments, at least ten interested parties reached out, wanting to order exactly the same from us.

JS: The interior is an integral part of each of our designs. We consider it an essential part of the project. We just don’t want to end up in the position of exterior skin designers or apartment designers.

How did you get to projects for the public sector, which have the potential to reach a much wider audience than a private family house?

VN: A young ambitious mayor from Terezín in southern Moravia found us on the web and contacted us, stating that he needed to build a small morgue of 3x3m at the cemetery. Then came additional smaller tasks such as sidewalks in the cemetery and gradually the scope grew from a winery museum to the renovation of a cultural house.

|

| Family house with an atrium in Podluží |

You became the main municipal architects, after all.

JS: If we were to recite contracts saying they are too small, then we would never get to work. Initially, we were not even profitable, but we sensed that we were doing something good for the right people, which was confirmed over time. After completion, we saw how people used the sports complex we designed and were satisfied, which was a significant asset for the future.

VN: Speaking of acquiring projects, a story about Bjarke Ingels comes to mind, where he couldn’t find his partner for tennis, which also happened to someone on the next court, and aside from playing a few sets, he gained an investor for several residential complexes in Copenhagen. Similarly, I went on a vacation with cyclists, among whom was the owner of a glass factory, whom we helped solve one renovation, and since then, she regularly approaches us with additional commissions.

Currently, your office has around ten employees, which allows you to work on large commissions like the covered swimming pool in Kyjov.

JS: After private clients, larger companies began to approach us. Most likely, we wouldn’t manage to work on three multifunctional buildings simultaneously at the level of executive projects. The design of houses and studio projects is still manageable by two people. However, we want to maintain control over all design phases, consult continuously, present to all committees, obtain authority statements, and see them through to realization. Realization is the art of compromise.

|

| Viladům Máj in Prague |

So you consider the current size to be ideal for keeping track of everything that is happening?

VN: We entrust larger projects to more experienced architects in our office. We have a hierarchy set up, but everyone has the opportunity to express their opinion. Even an intern can have a great idea, and we don't exclude the possibility that it will be reflected in the project and subsequent realization. We assign small contracts to students to design them themselves and go through all the phases. This way, they take ownership of the project. We don't want interns in the position of mere redrawers of our sketches.

JS: On the other hand, however, we know every project down to the last detail. We don’t want to end up in a situation where we’re sitting at home while a group of strangers under our brand designs houses.

Your first joint project was for Urban Interventions, which was in some way a charitable manifesto. Did you later participate in similar actions? Do you participate in architectural competitions?

JS: We attend invited competitions, where they cover our entry costs.

VN: We always had so much work that there was no need to strive for additional forms of competition. We want to finish work sensibly, operate under normal conditions, and not work at nights.

JS: We don’t know exactly how it happened, but we have been approached by major development companies like Trikaya or Crestyl, so we are getting interesting commissions.

VN: We have entered the consultation of public spaces and railway stops through the traffic-engineering association Laboro. In this transport world, there are many restrictions and interests, where the architect has very few options, but we still strive to improve these spaces. It’s like a state within a state with a heap of regulations, where everyone expresses their opinion on the project, but no one can make a firm decision, even though it’s a small contract.

|

| Weekend house in Bukovany |

You have entered the forbidden world previously accessible only to staticians and engineers. Roman Koucký similarly paved the way for architects to design bridges.

JS: We are not afraid of any contracts or typologies. When we are invited to propose a stop or something we have not done before, we quickly study everything accordingly.

We do not aim solely for ever larger construction scales, but now we have been approached by the owner of an office furniture factory and we are designing a modular furniture series A Look, which we presented at Mobitex and received third prize. In the factory, we developed prototypes, addressing production opportunities on-site. Unlike public administration, everything proceeded quickly and flexibly.

VN: We started designing furniture just before the outbreak of the coronavirus, after which all offices closed, and people moved to home offices, which will most likely also reflect in the future typology of administrative buildings.

Humans are social creatures, so people will want to return to offices. The delay in the project at least gives more time to think everything over.

VN: Architecture is a slow process. Now we are starting to build what we designed six years ago.

|

| Apartment building in the center of Luhačovice |

Koolhaas claims he manages to realize one project out of ten. How is it with you?

VN: At least half, but rather two-thirds of the projects eventually get built. Koolhaas and similar architects are visionaries who build unusual things where the outcome is not clear in advance, and in the end, neither is the client satisfied.

JS: These architects have a sculptural approach based on external astonishment, which is precisely the opposite of us.

VN: Their architecture seeks attention, revives spaces, and can diverge from the usual production. Alongside these stars are ordinary houses that shape the urban structure, and it definitely cannot be said that they are worse. Our practice is based on rationality and client satisfaction.

VN: People intuitively do not want to spend time in an ugly environment. However, the general idea of what is beautiful differs. Every good building initiates the emergence of other beautiful buildings in its vicinity.

JS: We have no problem praising good work by colleagues and sincerely wish that more realizations by other studios grow in the same place. We all want to improve the environment in which we live. There’s no disgraceful theme, only disgraceful results. Some would like to design only churches or galleries, but we spend more time in shopping centers, so our efforts to improve should be directed in this direction.

VN: Our architecture is not an 'eyecatcher' that programmatically attracts attention, but rather about higher quality execution and satisfying use. We create a good environment where the SENAA label won’t always be in sight.

It’s necessary to know when to stop in order to prevent a deviation from pompousness into a position of excessive asceticism.

VN: We certainly do not choose the cheapest materials and admit that our buildings are relatively expensive to execute. There is a big difference between furniture made from pallets that screams cheapness from afar. We invest in materials and details so that everything ends up looking ordinary.

JS: My grandfather used to say that it’s beautiful to watch figure skating, where all movements are synchronized, muscles are properly engaged, and the outcome appears very natural, light, and effortless. But years of hard work and maximum concentration on the result hide behind it.

|

| Covered swimming pool in Kyjov |

Do you have any dream projects or do you sketch into a drawer?

VN: Now our dream is for the swimming pool in Kyjov to be successfully completed. We believe that this could lead to other public buildings. A school, church, or museum are the highest we can aspire to as architects because that touches a wide spectrum of people.

JS: For example, we were invited to participate in a competition for the redevelopment of the Research Institute of Building Materials on Kaštanová Street in Brno, where there is a plan to build an administrative center with LEED certifications and sustainable methods of design within fifteen years. The automotive company Toyota approached us with a commission for the main entrance building, including a recruitment and training center in Kolín. New real projects keep appearing, so we no longer have time to sketch visions into a drawer.

JS: Recently, in addition to public administration and large enterprises, young investors have started to contact us who realize there are more lasting values than just quick profits.

VN: Previously, they actively traded stocks, and at a certain age, they began to consider what tangible and valuable will remain after them.

JS: Referring to the Brno example of Kaštanová, investors do not wish for just another office complex, but think about the carbon footprint left behind. Prague developers no longer just want to build and sell quickly, but realize the added value of architecture and cultivate the environment, which is great news for our profession.

Interviews with both architects took place on May 17, June 1, and June 15, 2021, in the Brno studio SENAA at Jakubské náměstí.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment

Related articles

0

28.10.2024 | Interview with Václav Hlaváček

0

21.01.2024 | Interview with Martin Prokš and Marek Přikryl

0

06.04.2022 | Interview with Roman Brychta

0

18.03.2022 | To the Prostějov exhibition Ten Years of SENAA Architects

0

17.03.2022 | Ten Years of SENAA - Invitation to the Exhibition in Prostějov

0

25.10.2021 | To the exhibition Ten Years of SENAA Architects

0

11.10.2021 | Ten Years of SENAA Architects - Invitation to the Exhibition in Kyjov