Interview with Martin Prokš and Marek Přikryl

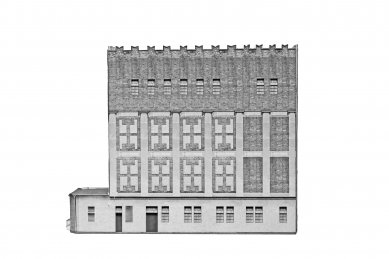

The festive opening of the reconstructed site of the former Automatic Mills in Pardubice in September can undoubtedly be considered the biggest architectural event of last year, not only because a significant industrial monument designed a hundred years ago by Josef Gočár was successfully saved, but also because it connected the efforts of three investors with a quartet of architects. The project was initiated by the Smetana couple, who auctioned the entire complex of Automatic Mills from the Winternitz brothers in 2015 and, together with Zdenek Balík from the Pardubice Zette studio, created the revitalization project, to which two public institutions were later invited. In 2018, the main building was purchased by the Pardubice Region, which relocated the Gočár Gallery here after the reconstruction by Petr Všetečka and Robert Václavík from the Brno studio Transat. The youngest of the trio of authors are Šépka's students Martin Prokš and Marek Přikryl, who reconstructed the grain silo for Lukáš Smetana into a cultural and social center. In mid-October, we visited Prokš and Přikryl in their Prague studio on Janáčkovo waterfront and asked them several questions.

Let's start with the obligatory question, how did you come together?

Marek: We just answered this question a week ago for Karolína Vránková in the show Bourání.

Great, so you already have a rehearsed answer. I prepared for the interview by listening to Mark's nine-year-old interview with Karolína Jirkalová also for the show Bourání, where he answered the same question, but maybe we’ll learn something new.

Marek: We met at ČVUT, where about two hundred freshmen entered the Faculty of Architecture in 2004, and groups of ten people were formed alphabetically into ZAN (Foundations of Architectural Design - a subject at the FA ČVUT, editor's note).

Martin: Prokš, Přikryl, Ptáčník...

It really depends a lot on whether one is lucky with a studio leader, whom one cannot choose.

Marek: We were not satisfied with the assigned ZAN, so Martin, another friend, Martin Ptáčník, and I gathered and went to Professor Šrámková to see if she would take us into her studio. By the second semester, we were already studying with her, which was figuratively and literally several floors higher.

I thought this legend of Czech architecture only supervised diploma students at the faculty.

Martin: She took us. She led consultations across the years.

Marek: It was on the 12th floor, a studio with a black floor and a wide American couch.

Martin: We spent another semester with Professor Šrámková after ZAN in our second year. The next semester we were somewhere else and then we all applied together to the studio of Hájek&Šépka.

What made you decide to go to Honza Šépka?

Marek: At the end of the fourth semester, we applied for a trip organized by Kruh focused on Swiss architecture, led by Marcela Steinbachová. Hájek and Šépka also went, as they were then leading the studio together. A fantastic trip in every way, classically by bus. That was in 2005. That’s how we met.

Martin: After returning from the excursion, the fifth semester began, during which applications to studios were made. Based on portfolios, they selected twenty students, including us, and we stayed with them until graduation.

Was it tolerable to spend most of your studies in one studio?

Marek: They rotated in leadership. Sometimes Hájek was the studio leader with assistant Šépka, and the next year they swapped roles. At the time we applied to them, they were just finishing the Archdiocesan Museum in Olomouc. They were at the peak, they had an aura about them. They created a fresh studio. They were thirty-five.

Martin: They had great assignments; often they were hybrid buildings combining multiple functions, or places with some handicap, limit, or challenge. And they always had top critiques at the end.

So you connected in the first year at the faculty, and did you also work together on some projects outside of school?

Martin: We competed a lot. We won a student competition for Revit for a meteorological tower in the Králický Sněžník mountain range. Towards the end of our studies, we won an idea competition for an extension of a kindergarten on the roof of the New Scene of the National Theatre in Prague.

How did you manage it?

Martin: We enjoyed it. We didn’t perceive it as a burden.

Marek: For first place in the competition, we received AutoCAD 2009 from Revit and said to ourselves how we would split the CD. Ultimately, after school, we founded a joint office, and we still use that software nowadays; the lines in CAD are still the same.

After graduation with Honza Šépka, Marek decided to continue his studies at AVU, and Martin started working with Tomáš Hradečný, who was the third of the former HŠH partners.

Martin: I worked for three-quarters of a year with Petr Hájek, as he was finishing the KCEV in Vrchlabí.

Marek: We graduated at a time when HŠH split into three independent studios after ten years of cooperation, which also affected the school; Šépka no longer taught with Hájek. It was a pity; together, they were stronger. They complemented and opposed each other.

Martin: Petr Hájek shared an attic space on Grafická Street near Smíchov's Anděl with Tomáš Hradečný. At that time, Tomáš asked me if I would like to collaborate on the project Vrbatova bouda. For some time I worked with Markéta Zdebská, who also had just graduated and founded the studio BY architects in 2010. Then I focused more on my projects and collaborated with Marek.

So Martin had experience from other studios, but Marek jumped into practice directly during AVU.

Marek: Martin approached me in 2011 to start a studio. It was his initiative.

Martin: By then, I already had some projects and also started to develop the project of the biotope in Honětice. It involved a private investor who posted an ad on an architecture website, stating that he owned a farm and was looking for its use. The property looked terrible, but we went for it. Other studios also responded to the ad, so he organized a small competition. Our proposal caught his attention the most, and we have been working with him ever since.

If I’m not mistaken, you keep returning to the site.

Marek: The biotope opened in 2013.

Martin: We are still doing things there. Currently, we are transforming the former barn into a wedding orangery.

In the back part of the area are former horse stables that are expected to be converted into accommodation. The investor is very active; he keeps building. A few kilometers away, he acquired another farm, from which he would like to create a second Honětice.

Could you sum up what the strongest thing you took away from the master studios of Hájek, Šépka, Přikryl or Šrámková was?

Marek: Everyone emphasized the concept, the idea, but each in a different way. The approaches to teaching were quite different.

Martin: HŠ cared that architecture was not self-serving. So that you don’t get into the likes-dislikes position but know well why you are doing it. And what it is really about. That was their common question.

Marek: Being able to describe and defend your project in one or two sentences.

Your transformation of the Pardubice silo reminds me in some ways of the early projects of HŠH.

Martin: That surprises me - could you elaborate on that a bit more?

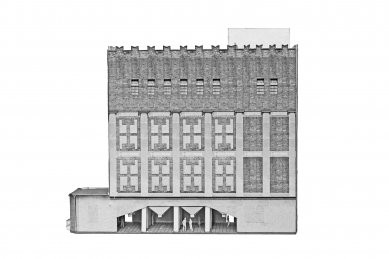

A simple intervention where you leave visible installations, you revealed the brick casing to expose the reinforced concrete load-bearing structure. To a large extent, you avoided atypical solutions.

Martin: Inside, all rational interventions, just like the building itself. We like a civil expression, rawness, materials. We don’t mind ordinary things; on the contrary.

Marek: However, we felt that the façades demanded an adequate intervention, different from the adjustments inside the building. Therefore, a new large opening was created in the base, and windows in that part were bricked up to highlight it.

However, when one looks at the overall visualization, the project seems to be at halftime because the central square lacks an eastern façade in the form of several houses designed by Zdeněk Balík. What is the status of the completion?

Marek: Zdeněk Balík mainly found the key to how to develop the premises; he found the urbanism. He likes to use the word "key," and I think it’s apt. He then proposed the line of new buildings that will close the ensemble. All his designs are very artistic; it’s going to be an event; I’m looking forward to it. These buildings exceed the surrounding scale, but the Mills have always been an exception in that respect.

Martin: The mills now lack a normal café. There is one in the Gočár Gallery, but it is more turned towards the Chrudimka river, as if it had its back to the grounds. It is not accessible from the square but from the passage. Zdeněk Balík drew a restaurant on the site of the former stables, which should be the first built house of the next phase. This is crucial for life in the area.

When part of the complex was sold to the region and the city, there were already completed projects. Who selected the architects for individual buildings at that time? Or who specifically contacted your studio for the commission?

Martin: When part of the mills was sold to the region, it included the project of Petr Všetečka, and similarly, the city purchased the land with the project of Jan Šépka. Those were the sales conditions, and that’s how everything functioned mutually. Multiple approaches came together here, which is good. If just one author had taken over the entire area, whoever it might have been, it would certainly have lost some tension between the individual buildings that exist today.

Marek: Architects Všetečka, Šépka – those were purely authorial selections by Lukáš Smetana and Zdeněk Balík.

And when did you get involved in the project?

Martin: In 2018. Zdeněk Balík, just like us, studied with Šépka and Hájek. Only for one semester, but Šépka made a strong impression on him, so he recommended him to Lukáš Smetana. And subsequently, Šépka recommended us to reconstruct the silo.

As his students who spent a lot of time in his studio.

Martin: I think he liked Honětice. Perhaps based on those raw and simple adjustments. But Zdenda Balík had contacted us before, saying he liked what we were doing.

When I look at your previous work, you mostly intervene in existing buildings and build upon them. You rarely build on green fields.

Martin: It is somewhat coincidental, but at the same time, we feel strong in this area. If a place has a story, it can be built upon. Limits, difficulties, all of that is essentially beneficial.

Marek: The only greenfield project remains the house with a ramp. At that time, we met with the investor in a freshly parceled field outside Prague, with nothing around. The only thing we could latch onto was the slope of the terrain. Perhaps the view. That’s why a ramp became the motif of the whole house, along with large windows.

How did the brief for the silo evolve?

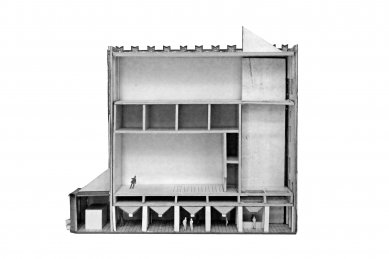

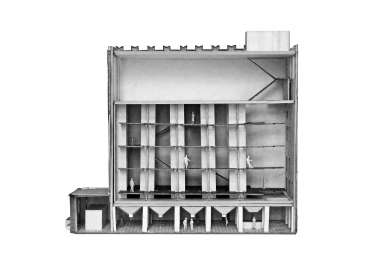

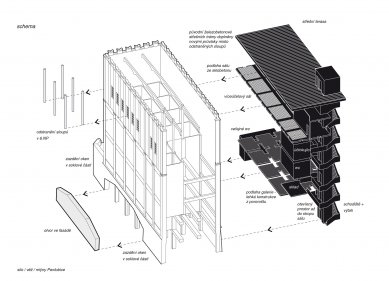

Marek: Initially, it was considered to intervene more in the grain storage than what ultimately happened. The reinforced concrete grid would certainly withstand the boring. We originally planned to place two halls inside the structure; that was the first version “black box – white box.” The black box was to be cut into the storage, completely without windows, while the white box would be a counterpoint on the upper floor with windows, with the original white lime plaster. However, in the end, no justification was found for such a radical and irreversible intervention. The hall would not offer anything extraordinary besides its peculiar placement.

Martin: Another working variant was a spatial mesh of walkways that would lead the visitor all the way up. Only the axial crosses would remain from the silos, with pathways woven between them. But it was the same as with the black box; the silos would practically no longer exist in their original form.

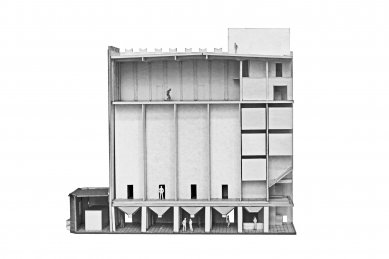

Marek: Only the upper hall remained. The walkways were also realized, but only in the form of a path through the storage, nothing more. Nothing less. They were preserved in their size. Meanwhile, the idea of opening the building to the square developed, which went hand in hand with the overall opening of the site to the city after more than a hundred years. Opening the gates, opening the base. We also opened the brick base, which had hitherto been mysteriously closed. The uncovered storage gave a covered space atmosphere. Gočár’s mystique also lies in the fact that he designed the base as a massive pedestal, even though the real structure is the skeleton behind it.

During the reconstruction, the entire silo was floating on exposed concrete columns. Did you also play with the idea of leaving the construction exposed like that?

Martin: When it was stripped down to the skeleton, it was impressive. There was a hole in the ground below the storage, literally a pool. Leaving such an exposed basement would be structurally unrealistic. Also operationally. It would be a statue.

Marek: That brick base belongs to the spirit of the place; it is rightly there. The mill has it, and so does the silo.

Martin: The basement could have been made because the columns are founded deeper than we expected in our studies. That only became clear during construction. This allowed us to excavate the ground, expose the columns, and create a functional basement.

Marek: There is a low ceiling here, massive columns everywhere; we call them elephant legs, and above our heads are glass concrete panels. It has something about it; it’s kind of an underworld. It's one of the few changes in the volume of the building, albeit invisible.

Martin: I'd also mention that window, or rather opening, through which grain was poured into the underground storage. From there, it was lifted up and then dropped through various filters back down and then back up into the silos. We acknowledged that opening, and now it provides light to the staircase; it has a sill at sidewalk level; it's somewhat of an exception in the western façade.

Marek: That constant movement of grain up and down, the vertical movement simply, the verticality is something we wanted to remind with the deep space of the staircase across all floors.

Is a café planned for the covered space under the storage in the future?

Marek: No. It's purely an expansion of public space.

Martin: It is also the main entrance. The restaurant is planned directly opposite.

Marek: Unlike the surrounding buildings, the silo does not have a fixed program, which makes it different and more自由. It's more a cluster of spaces and opportunities, including the base with the storage.

The silo is connected to the regional gallery at the level of the upper hall by a bridge. Can the hall serve the neighboring gallery or vice versa?

Marek: Theoretically, but in reality, it is not possible. It is basically a locked corridor.

Martin: The arch remains unused; it’s a pity. The border between the region and the investor runs through it, which is the main reason why the arch could not be more integrated into the silo. On the opposite side of the bridge are the offices of the management of Gočár’s Gallery, which means that operational connections are not possible today and probably won’t be.

Marek: During the design phase, we considered that at least it could leak through the arch. This would increase the capacity of the hall from a fire safety point of view. But that wasn’t feasible. Safety, legal reasons...

What are your views on topics that are impacting not only contemporary architecture, such as ecology and sustainability?

Martin: We probably keep our distance. Sustainability for us is more about utilizing existing buildings instead of new constructions. We do not deliberately pursue green roofs, heat pumps. Or the mentioned kindergarten on the roof – that is an increase in the plot area, preventing the loss of open space.

Marek: At the same time, we have realized over the years that there is no need to cling to preserving everything at all costs. If a technical problem arises with masonry or wooden elements, it’s better to start anew. One should act rationally in these moments.

The Pardubice silo is so far your largest project in terms of scope and budget. This could potentially make it a springboard for acquiring other interesting projects due to the expected media coverage.

Martin: We are lucky that we always work on something that somewhat deviates from the norm. There is a very low probability that we would work second time on the revitalization of a grain silo or old tractor garages. The uniqueness of these buildings will not guarantee us further similar projects.

Perhaps this type of atypical assignment gives you freedom. Do investors approach you repeatedly?

Marek: Probably yes; it does give freedom. But it has its two sides.

Martin: But there are exceptions. We still have items on the table for Igor Pokorný in Honětice. Besides that, we received a contact through Honza Žalský for the structural engineer Jan Bursa, who wanted to participate in the competition for the bridge to Jaroměř. In the end, that competition was won by Mirko Baum, that was in 2013. In the meantime, we got to know each other better, and since then we have participated in other bridge competitions with him.

Marek: We clicked in some way, and occasionally we design for him or help out.

Martin: For him, for example, we created the office extension in Vysoké Mýto, where he is headquartered.

It is a three-story wooden tower clad in aluminum. We wanted it to blend into the mix of diverse buildings in the courtyard in terms of silhouette and scale. We modified the interior of his house. And in his garden, we designed a sauna for him.

Marek: His office also evaluated and drafted the concrete work on the Pardubice silo. While the silo looks the same from the outside, it was not entirely easy from the perspective of new constructions. The building was underpinned, a white bathtub was inserted, the floor of the hall, the roof – all of those are new constructions. The façade at the level of the hall on the sixth floor is merely a thirty-centimeter-thick brick reinforced with pilasters and slender concrete columns. All of this is with a free height of six meters. New columns in a C shape were added to the original columns, which is why the walls of the hall are so sculptural.

Martin: Regarding the original concrete, all were in very good condition; no renovation was necessary. According to diagnostics, these are concretes around class C16/20, some even better. The skeleton was essentially left as it was, including the patina, paint, or scars left by partitions. The concrete inside the silos was merely washed with water.

Marek: Exactly one hundred years later, the function of the building is changing from industrial to social. Let’s hope for another hundred years. Essentially, it was just washed.

A nice ending. Thank you for the interview!

The interview took place on October 16, 2023, at the Prokš Přikryl Architects studio on Janáčkovo waterfront 5 in Prague

|

| Ing. arch. MgA. Marek Přikryl (*1983 Prague) and Ing. arch. Martin Prokš (*1980 Jihlava) in the Prague studio on Janáčkovo waterfront. |

Let's start with the obligatory question, how did you come together?

Marek: We just answered this question a week ago for Karolína Vránková in the show Bourání.

Great, so you already have a rehearsed answer. I prepared for the interview by listening to Mark's nine-year-old interview with Karolína Jirkalová also for the show Bourání, where he answered the same question, but maybe we’ll learn something new.

Marek: We met at ČVUT, where about two hundred freshmen entered the Faculty of Architecture in 2004, and groups of ten people were formed alphabetically into ZAN (Foundations of Architectural Design - a subject at the FA ČVUT, editor's note).

Martin: Prokš, Přikryl, Ptáčník...

It really depends a lot on whether one is lucky with a studio leader, whom one cannot choose.

Marek: We were not satisfied with the assigned ZAN, so Martin, another friend, Martin Ptáčník, and I gathered and went to Professor Šrámková to see if she would take us into her studio. By the second semester, we were already studying with her, which was figuratively and literally several floors higher.

I thought this legend of Czech architecture only supervised diploma students at the faculty.

Martin: She took us. She led consultations across the years.

Marek: It was on the 12th floor, a studio with a black floor and a wide American couch.

Martin: We spent another semester with Professor Šrámková after ZAN in our second year. The next semester we were somewhere else and then we all applied together to the studio of Hájek&Šépka.

|

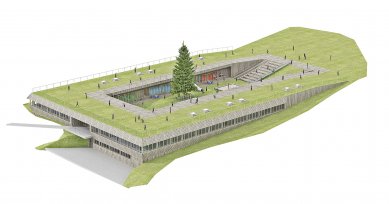

| The kindergarten on the roof of the operational building of the National Theatre (2009), 1st place in the KOMA conceptual competition in the Young Architect Award category. |

What made you decide to go to Honza Šépka?

Marek: At the end of the fourth semester, we applied for a trip organized by Kruh focused on Swiss architecture, led by Marcela Steinbachová. Hájek and Šépka also went, as they were then leading the studio together. A fantastic trip in every way, classically by bus. That was in 2005. That’s how we met.

Martin: After returning from the excursion, the fifth semester began, during which applications to studios were made. Based on portfolios, they selected twenty students, including us, and we stayed with them until graduation.

Was it tolerable to spend most of your studies in one studio?

Marek: They rotated in leadership. Sometimes Hájek was the studio leader with assistant Šépka, and the next year they swapped roles. At the time we applied to them, they were just finishing the Archdiocesan Museum in Olomouc. They were at the peak, they had an aura about them. They created a fresh studio. They were thirty-five.

Martin: They had great assignments; often they were hybrid buildings combining multiple functions, or places with some handicap, limit, or challenge. And they always had top critiques at the end.

So you connected in the first year at the faculty, and did you also work together on some projects outside of school?

Martin: We competed a lot. We won a student competition for Revit for a meteorological tower in the Králický Sněžník mountain range. Towards the end of our studies, we won an idea competition for an extension of a kindergarten on the roof of the New Scene of the National Theatre in Prague.

|

| Meteorological tower in the Králický Sněžník mountain range (2008), 1st place in the Revit competition |

How did you manage it?

Martin: We enjoyed it. We didn’t perceive it as a burden.

Marek: For first place in the competition, we received AutoCAD 2009 from Revit and said to ourselves how we would split the CD. Ultimately, after school, we founded a joint office, and we still use that software nowadays; the lines in CAD are still the same.

After graduation with Honza Šépka, Marek decided to continue his studies at AVU, and Martin started working with Tomáš Hradečný, who was the third of the former HŠH partners.

Martin: I worked for three-quarters of a year with Petr Hájek, as he was finishing the KCEV in Vrchlabí.

Marek: We graduated at a time when HŠH split into three independent studios after ten years of cooperation, which also affected the school; Šépka no longer taught with Hájek. It was a pity; together, they were stronger. They complemented and opposed each other.

Martin: Petr Hájek shared an attic space on Grafická Street near Smíchov's Anděl with Tomáš Hradečný. At that time, Tomáš asked me if I would like to collaborate on the project Vrbatova bouda. For some time I worked with Markéta Zdebská, who also had just graduated and founded the studio BY architects in 2010. Then I focused more on my projects and collaborated with Marek.

|

| Extension of Vrbatova bouda (2010-15), general designer Tomáš Hradečný / IXA |

So Martin had experience from other studios, but Marek jumped into practice directly during AVU.

Marek: Martin approached me in 2011 to start a studio. It was his initiative.

Martin: By then, I already had some projects and also started to develop the project of the biotope in Honětice. It involved a private investor who posted an ad on an architecture website, stating that he owned a farm and was looking for its use. The property looked terrible, but we went for it. Other studios also responded to the ad, so he organized a small competition. Our proposal caught his attention the most, and we have been working with him ever since.

If I’m not mistaken, you keep returning to the site.

Marek: The biotope opened in 2013.

Martin: We are still doing things there. Currently, we are transforming the former barn into a wedding orangery.

In the back part of the area are former horse stables that are expected to be converted into accommodation. The investor is very active; he keeps building. A few kilometers away, he acquired another farm, from which he would like to create a second Honětice.

|

| The biotope facilities in Honětice near Kroměříž (2013) |

Could you sum up what the strongest thing you took away from the master studios of Hájek, Šépka, Přikryl or Šrámková was?

Marek: Everyone emphasized the concept, the idea, but each in a different way. The approaches to teaching were quite different.

Martin: HŠ cared that architecture was not self-serving. So that you don’t get into the likes-dislikes position but know well why you are doing it. And what it is really about. That was their common question.

Marek: Being able to describe and defend your project in one or two sentences.

Your transformation of the Pardubice silo reminds me in some ways of the early projects of HŠH.

Martin: That surprises me - could you elaborate on that a bit more?

A simple intervention where you leave visible installations, you revealed the brick casing to expose the reinforced concrete load-bearing structure. To a large extent, you avoided atypical solutions.

Martin: Inside, all rational interventions, just like the building itself. We like a civil expression, rawness, materials. We don’t mind ordinary things; on the contrary.

Marek: However, we felt that the façades demanded an adequate intervention, different from the adjustments inside the building. Therefore, a new large opening was created in the base, and windows in that part were bricked up to highlight it.

However, when one looks at the overall visualization, the project seems to be at halftime because the central square lacks an eastern façade in the form of several houses designed by Zdeněk Balík. What is the status of the completion?

Marek: Zdeněk Balík mainly found the key to how to develop the premises; he found the urbanism. He likes to use the word "key," and I think it’s apt. He then proposed the line of new buildings that will close the ensemble. All his designs are very artistic; it’s going to be an event; I’m looking forward to it. These buildings exceed the surrounding scale, but the Mills have always been an exception in that respect.

Martin: The mills now lack a normal café. There is one in the Gočár Gallery, but it is more turned towards the Chrudimka river, as if it had its back to the grounds. It is not accessible from the square but from the passage. Zdeněk Balík drew a restaurant on the site of the former stables, which should be the first built house of the next phase. This is crucial for life in the area.

|

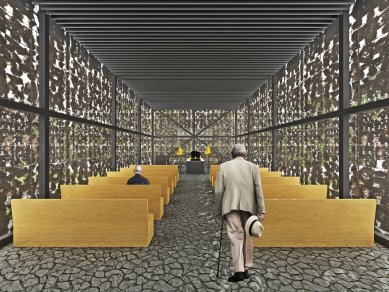

| Installation of the exhibition German Design: German design. Past – Present (2013) co. M. Pukl |

When part of the complex was sold to the region and the city, there were already completed projects. Who selected the architects for individual buildings at that time? Or who specifically contacted your studio for the commission?

Martin: When part of the mills was sold to the region, it included the project of Petr Všetečka, and similarly, the city purchased the land with the project of Jan Šépka. Those were the sales conditions, and that’s how everything functioned mutually. Multiple approaches came together here, which is good. If just one author had taken over the entire area, whoever it might have been, it would certainly have lost some tension between the individual buildings that exist today.

Marek: Architects Všetečka, Šépka – those were purely authorial selections by Lukáš Smetana and Zdeněk Balík.

And when did you get involved in the project?

Martin: In 2018. Zdeněk Balík, just like us, studied with Šépka and Hájek. Only for one semester, but Šépka made a strong impression on him, so he recommended him to Lukáš Smetana. And subsequently, Šépka recommended us to reconstruct the silo.

As his students who spent a lot of time in his studio.

Martin: I think he liked Honětice. Perhaps based on those raw and simple adjustments. But Zdenda Balík had contacted us before, saying he liked what we were doing.

When I look at your previous work, you mostly intervene in existing buildings and build upon them. You rarely build on green fields.

Martin: It is somewhat coincidental, but at the same time, we feel strong in this area. If a place has a story, it can be built upon. Limits, difficulties, all of that is essentially beneficial.

Marek: The only greenfield project remains the house with a ramp. At that time, we met with the investor in a freshly parceled field outside Prague, with nothing around. The only thing we could latch onto was the slope of the terrain. Perhaps the view. That’s why a ramp became the motif of the whole house, along with large windows.

|

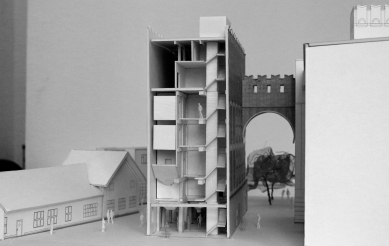

| House with a ramp (2015) |

How did the brief for the silo evolve?

Marek: Initially, it was considered to intervene more in the grain storage than what ultimately happened. The reinforced concrete grid would certainly withstand the boring. We originally planned to place two halls inside the structure; that was the first version “black box – white box.” The black box was to be cut into the storage, completely without windows, while the white box would be a counterpoint on the upper floor with windows, with the original white lime plaster. However, in the end, no justification was found for such a radical and irreversible intervention. The hall would not offer anything extraordinary besides its peculiar placement.

Martin: Another working variant was a spatial mesh of walkways that would lead the visitor all the way up. Only the axial crosses would remain from the silos, with pathways woven between them. But it was the same as with the black box; the silos would practically no longer exist in their original form.

Marek: Only the upper hall remained. The walkways were also realized, but only in the form of a path through the storage, nothing more. Nothing less. They were preserved in their size. Meanwhile, the idea of opening the building to the square developed, which went hand in hand with the overall opening of the site to the city after more than a hundred years. Opening the gates, opening the base. We also opened the brick base, which had hitherto been mysteriously closed. The uncovered storage gave a covered space atmosphere. Gočár’s mystique also lies in the fact that he designed the base as a massive pedestal, even though the real structure is the skeleton behind it.

|

| Adaptation of the grain silo in Pardubice (2018-23) |

During the reconstruction, the entire silo was floating on exposed concrete columns. Did you also play with the idea of leaving the construction exposed like that?

Martin: When it was stripped down to the skeleton, it was impressive. There was a hole in the ground below the storage, literally a pool. Leaving such an exposed basement would be structurally unrealistic. Also operationally. It would be a statue.

Marek: That brick base belongs to the spirit of the place; it is rightly there. The mill has it, and so does the silo.

Martin: The basement could have been made because the columns are founded deeper than we expected in our studies. That only became clear during construction. This allowed us to excavate the ground, expose the columns, and create a functional basement.

Marek: There is a low ceiling here, massive columns everywhere; we call them elephant legs, and above our heads are glass concrete panels. It has something about it; it’s kind of an underworld. It's one of the few changes in the volume of the building, albeit invisible.

Martin: I'd also mention that window, or rather opening, through which grain was poured into the underground storage. From there, it was lifted up and then dropped through various filters back down and then back up into the silos. We acknowledged that opening, and now it provides light to the staircase; it has a sill at sidewalk level; it's somewhat of an exception in the western façade.

Marek: That constant movement of grain up and down, the vertical movement simply, the verticality is something we wanted to remind with the deep space of the staircase across all floors.

|

| Exposed foundations of the Pardubice silo. |

Is a café planned for the covered space under the storage in the future?

Marek: No. It's purely an expansion of public space.

Martin: It is also the main entrance. The restaurant is planned directly opposite.

Marek: Unlike the surrounding buildings, the silo does not have a fixed program, which makes it different and more自由. It's more a cluster of spaces and opportunities, including the base with the storage.

The silo is connected to the regional gallery at the level of the upper hall by a bridge. Can the hall serve the neighboring gallery or vice versa?

Marek: Theoretically, but in reality, it is not possible. It is basically a locked corridor.

Martin: The arch remains unused; it’s a pity. The border between the region and the investor runs through it, which is the main reason why the arch could not be more integrated into the silo. On the opposite side of the bridge are the offices of the management of Gočár’s Gallery, which means that operational connections are not possible today and probably won’t be.

Marek: During the design phase, we considered that at least it could leak through the arch. This would increase the capacity of the hall from a fire safety point of view. But that wasn’t feasible. Safety, legal reasons...

What are your views on topics that are impacting not only contemporary architecture, such as ecology and sustainability?

Martin: We probably keep our distance. Sustainability for us is more about utilizing existing buildings instead of new constructions. We do not deliberately pursue green roofs, heat pumps. Or the mentioned kindergarten on the roof – that is an increase in the plot area, preventing the loss of open space.

Marek: At the same time, we have realized over the years that there is no need to cling to preserving everything at all costs. If a technical problem arises with masonry or wooden elements, it’s better to start anew. One should act rationally in these moments.

The Pardubice silo is so far your largest project in terms of scope and budget. This could potentially make it a springboard for acquiring other interesting projects due to the expected media coverage.

Martin: We are lucky that we always work on something that somewhat deviates from the norm. There is a very low probability that we would work second time on the revitalization of a grain silo or old tractor garages. The uniqueness of these buildings will not guarantee us further similar projects.

|

| Pedestrian bridge over the Elbe in Hradec Králové (2014), 3rd place in the competition (in collaboration with MDS Projekt and Mario Guisasola) |

Perhaps this type of atypical assignment gives you freedom. Do investors approach you repeatedly?

Marek: Probably yes; it does give freedom. But it has its two sides.

Martin: But there are exceptions. We still have items on the table for Igor Pokorný in Honětice. Besides that, we received a contact through Honza Žalský for the structural engineer Jan Bursa, who wanted to participate in the competition for the bridge to Jaroměř. In the end, that competition was won by Mirko Baum, that was in 2013. In the meantime, we got to know each other better, and since then we have participated in other bridge competitions with him.

Marek: We clicked in some way, and occasionally we design for him or help out.

Martin: For him, for example, we created the office extension in Vysoké Mýto, where he is headquartered.

It is a three-story wooden tower clad in aluminum. We wanted it to blend into the mix of diverse buildings in the courtyard in terms of silhouette and scale. We modified the interior of his house. And in his garden, we designed a sauna for him.

Marek: His office also evaluated and drafted the concrete work on the Pardubice silo. While the silo looks the same from the outside, it was not entirely easy from the perspective of new constructions. The building was underpinned, a white bathtub was inserted, the floor of the hall, the roof – all of those are new constructions. The façade at the level of the hall on the sixth floor is merely a thirty-centimeter-thick brick reinforced with pilasters and slender concrete columns. All of this is with a free height of six meters. New columns in a C shape were added to the original columns, which is why the walls of the hall are so sculptural.

Martin: Regarding the original concrete, all were in very good condition; no renovation was necessary. According to diagnostics, these are concretes around class C16/20, some even better. The skeleton was essentially left as it was, including the patina, paint, or scars left by partitions. The concrete inside the silos was merely washed with water.

Marek: Exactly one hundred years later, the function of the building is changing from industrial to social. Let’s hope for another hundred years. Essentially, it was just washed.

A nice ending. Thank you for the interview!

The interview took place on October 16, 2023, at the Prokš Přikryl Architects studio on Janáčkovo waterfront 5 in Prague

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment