ARCHIP: Landscape, Urbanism, Public Space

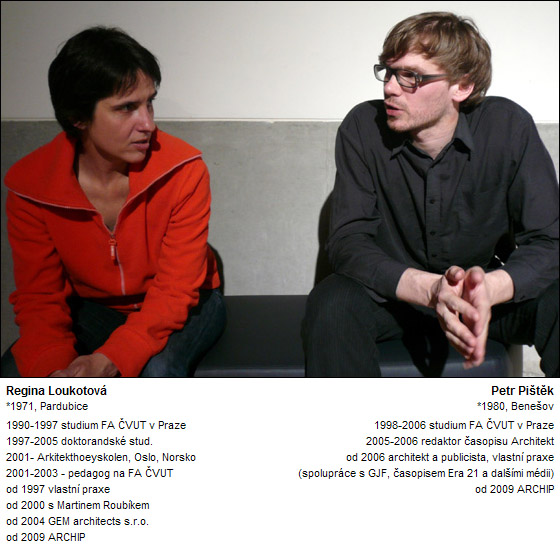

About the new school of architecture with Regina Loukotová and Petr Pištěk

Please provide the text you would like to have translated, and I'll assist you with that!

|

As can be seen from the date mentioned, this happened for the newly established institution at a rather inconvenient time – at a time when most aspiring architecture students had long submitted their applications and the majority already know the results. It is also evident that the first school year will not be easy for ARCHIP due to this handicap. Undoubtedly also because applicants will have to pay tuition fees compared to the customs established in the country for this field.

What are the new leadership’s ideas on how architecture should be properly taught? Should students have to pay for their studies? And what assignments will the first students tackle starting in October? We sought answers to these and other questions with the Rector Regina Loukotová and the Vice-Rector for Education Petr Pištěk.

|

If the public has been following the efforts to establish ARCHIP from a distance, they suspect that this is not a step that was decided last year, but rather a long-term endeavor. Do you still remember when and in what contemporary context the idea of establishing a private school of architecture in Prague arose?

Regina Loukotová: When I dig into my memory, it’s really the summer of 2001. At that time, Martin Roubík and I started to say that it would be good to teach architecture in Prague because other schools did not offer a comprehensive program in English. We were sitting with our friend Jiří Bárta, who lives in California, and we agreed to try organizing summer workshops first... It was supposed to be a kind of connection between the rest of the world and Prague, with teaching in a foreign language. Then came September 11, which compelled us to postpone our plans a bit, as it did not bring the most suitable time. However, the plan was already laid in our minds. Martin and I then taught for a while at local schools; the idea of our own school occasionally took a back seat, but it never left us. We were almost afraid that establishing a school of architecture was such a necessary and clear plan that someone would snatch it away from us.

Martin Roubík led the studio at the Faculty of Architecture of CTU from 1991-92 and 2000-03; you yourself taught at the same institution (2001–03). In 2005, you even ran for the position of dean there; Martin applied for the same position in 2002 and again two years later in Liberec. You have the opportunity to compare. Why do you think the foundation of Czech architectural education is insufficient?

RL: I believe it is good for both Czech and foreign students to have education in English. The main thing, however, is that we want to teach architecture, and we believe we can assemble excellent teachers. Many of them previously taught at other schools, some of them no longer teach, or have never taught and will start teaching now. We believe that such high-quality people should be teaching, and students deserve it.

Petr Pištěk: Compared to existing Czech schools, I would emphasize the ambition to be truly international. Students from all over the world, foreign teachers, contacts abroad... Because many things that here have been slowly and cautiously arriving over the last two decades and are perhaps beginning to work have long been invented in Europe or other parts of the world, and there is no reason not to learn from them. Or why not maintain contact with abroad? Because Czech architecture is often criticized for its closed nature, which often begins already in schools. However, I certainly do not claim that the situation at existing schools is not evolving and improving...

Can the criticisms of the current form of education be specified?

PP: It is essentially about problems that can be attributed to the entire Czech education system. An encyclopedic way of teaching, mutual disconnection between subjects, to a large extent academicism in assigning tasks, minimal communication between teachers and students, as well as among students themselves, lack of teamwork, negligible monitoring of current events... And last but not least, some unfriendly atmosphere. One enthusiastically studies for the entrance exams, and when one gets to school, they find that they are overwhelmed with seminar papers and other tasks that do not interest them, and the rest of the studies is endured with the feeling that they just have to make it through somehow. Which is a terrible disillusionment.

RL: I agree with the criticism; I would perhaps emphasize arrogance. When Martin ran for dean, he said that the first sentence a teacher should address a student with in the morning at school is: Good morning, what can I do for you today? Unfortunately, it still works in the opposite way. The inverted situation in the Czech Republic persists even after twenty years. The student-teacher relationship troubles a lot of people, in my opinion. Unfortunately, those who do not travel abroad are not aware of this distortion. Only in the environment of a school in Oslo or London do they see that the teacher is exactly the same person as them, and there is a discussion between them, and even the teacher sometimes admits they do not know something. And no student is elevated above others.

PP: Generally, I also miss critical thinking or reflection in schools. Even though grades are given at the end, it is not specified for what. And this approach is then reflected in how architecture is evaluated – whether generally or in professional media. We are not aware enough that it is not just a matter of opinion, that there are also certain arguments or even objective criteria in this field.

RL: I am also reminded of overlooked subjects, such as rhetoric. We are trying to incorporate it into the curriculum right from the first year, where it will be part of the subject Project Presentation. It is extremely important for an architect to be able to explain and defend their work meaningfully and concisely. Initially, we even wanted to teach musical composition...

STUDYING FOR MONEY

ARCHIP will undoubtedly be new within the Czech environment among architectural schools in that it is private, and thus students will have to pay for their education. The prestigious Architectural Association School of Architecture in London has been operating on the same principle for over 150 years. However, does a similar model of education also exist in Eastern or Central Europe?

RL: This question has also interested us. Recently, I went through the EAAE database – the Association of European Architectural Schools, looking for a clear answer. After ongoing verification, I believe there is no such school. There is supposedly a smaller private school in Berlin, but it focuses more on art than architecture. In Prague, North Carolina University has opened an architecture program, reportedly led by Martin Rajniš, but it is more about courses rather than a complete field. In Poland, Hungary, Austria, the successor states of former Yugoslavia, and in the Baltic states, we know of no such school. It seems that we will be the first in our Central Eastern region...

PP: When we examined the situation as a whole, we concluded that there probably are not many private architecture schools in Europe either. Besides the AA, we currently know of the Parisian École Spéciale d'Architecture, the Athenaeum in Lausanne, or the Norwegian school in Bergen.

And how do you explain their absence? Rather, is the private model viable in our environment?

PP: We believe we are not conceptually doing anything wrong.

RL: Of course, we have also thought about financial aspects. In the Czech Republic, we are, I believe, the 46th private university, with 95 percent of fields represented by economics, hotel management, management, or tourism – and for their education, you really only need, with a certain exaggeration, a table and a chair. Architecture is, of course, expensive: whether we are talking about workshops... Because we want students to model a lot. Or about computers or a library...

Similarly, there is no purely private law school, medical school, or natural science field in the Czech Republic. So could the reason be financial costs? I understand the situation in the Czech Republic: private universities began to be approved around 1998, and before that, they could not exist.

By the way, a Polish colleague wrote to me today, and when evaluating the situation at the technical university in Wrocław, he noted that they would also need a private school. So perhaps we have started a trend. (laughs)

However, as Petr said, we have not yet found an obstacle. However, if we compare good world schools, there are many private ones among them. Especially in America.

The private education system in the United States is based, among other things, on a sophisticated sponsorship system. Therefore, if we conclude that besides American universities, there is a clearly defined private school with an architectural focus primarily in London’s AA, does this represent a kind of model for you? Are you inspired by their system of education?

RL: Certainly. Our model was based on the Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon models.

PP: Perhaps starting with Bauhaus, even though it was state-run.

To a large extent, your concept of education can be inferred from the already outlined criticism of Czech education. Nevertheless, can you elaborate on it?

RL: The education at AA, like at AHO in Oslo, is concentrated more into blocks. Even here, primary schools are increasingly introducing an approach where the child does not have a separate geography subject and a separate history subject, but is educated in thematic blocks. So that they understand that things are interconnected. We have also tried to assemble subjects into blocks that run through the entire study. And we wanted to connect them and minimize their number. At AHO, for example, there are only three blocks: project, technology, theory, and history.

PP: For those interested, if they look at our study plan, they may not find a design that appears as progressive and block-like. The result is, to some extent, a compromise between our ideas and the model traditionally in the country and thus approved by the accreditation committee.

However, the important thing is not the names and numbers of subjects, but their content and the teachers – what and how is solved concretely in the subject. Even mathematics can be very entertaining. And this applies to everything.

Landscape, urbanism, public space. These are the cornerstones that the new school should uphold. They are also the themes that appear in our promotional materials. They are supposed to show that we want to move from the character of individual buildings mainly to the arrangement and functioning of the whole. As Igor Kovačević once told me, even decent contemporary buildings are produced by construction companies in catalogs today. At least decent at first glance. But to make the whole work so that the public space, including transport, functions well? For that, an ordinary designer alone is not enough, nor even a single building.

However, architecture is neither fine art. It is not a game based on random individual inspirations. But a pragmatic, professional profession and a service.

RL: To the cornerstones, I would add sustainability.

PP: However, we want to understand fields such as ecology and heritage conservation in a realistic and interconnected way. So that they do not represent incompatible prime-time militant positions.

Let’s return to finances – and thus tuition.

RL: In the Czech Republic, the ground is more challenging. Whether it is about health care or education. We are solving what is free and what is not. What possibly has a discount. Abroad, the situation is much more sophisticated, especially the system of bank loans. But we are also working on it here. Minister Kopicová is trying to negotiate with banks to establish a system of student loans. In Scandinavia, it is quite common for a person to repay a loan taken during school until they are sixty. The loan is, however, arranged very advantageously. Parents do not have to support their children while they are studying.

Education in architecture is simply expensive. We want to pay good teachers... We have negotiated offices and teaching spaces in the Veletržní Palace... The school will have heating and lighting... Studios will be equipped with computers and programs... All of this obviously costs money.

We need not repeat that there is no good library with architectural themes in Prague. And a good school must be based on a good library.

So, will you have your own library?

RL: Definitely. It is also one of the conditions for accreditation. Which is again an expensive matter. We have a foundation. But Adam Gebrian came up with a great idea: Every architect buys expensive representative books that they subsequently open at most once... So we could consider whether to start the library with those from the libraries of allied architects.

PP: The same situation exists with magazines. Perhaps with the difference that you may not even have time to open them.

But I would like to return to the tuition. People are questioning its amount...

...to be specific, it amounts to 90,000 crowns per semester.

PP: We are aware that for many candidates, this is a major issue regarding their potential choice. But on the other hand, let’s look at how much other private schools cost.

RL: By the way, we are not the most expensive, as was mistakenly stated in the media.

PP: Not to mention how much schools with foreign accreditation cost. That is, branches of foreign universities. Let’s compare how much today cooking courses or kindergartens cost.

RL: Or rather, let’s directly look at architecture schools. If the information available does not mislead us, foreign students pay 60,000 crowns per semester at the Faculty of Architecture in Prague. At Umprum, foreign students pay 90,000 per semester. This study simply costs that much.

PP: Last but not least, we must mention that we expect sixty students per year in the future. It will never be about anonymous masses. Tuition is also set in such a way that it is absolutely the same for both Czechs and foreigners from EU countries or anywhere else. No double or triple pricing. We strive to approach everyone equally.

RL: But the problem has a second side. We have received feedback from abroad that we are too cheap, and the school will not be taken seriously...

In principle, however, you do not have a problem with the notion that students pay for their education.

RL: ARCHIP is an exceptional school. Not all education should be free. Society must definitely be knowledgeable, and every person should have the right to education. In the Czech Republic, one can now choose from seven architecture schools. Therefore, the principle is indeed respected. Our school complements the spectrum.

PP: The problem is rather the current image of private schools. There is an effort to close and limit them rather, as it is known how things have worked and still work in some places... The Czech Republic also has one of the highest numbers of universities per capita. Thus, we were born into an unwelcoming time. On the other hand, we hold a somewhat exclusive position with our specialization. Among private schools, we form an absolute minority alongside Ondříček's Film Academy, the Litomyšl Institute of Restoration, which now falls under the Pardubice University, and one or two technical schools.

EDUCATION FOR PRACTICE

The guiding principle for the school's direction and further development is the scientific-artistic council. Your website does not currently list its composition. Will you reveal it now?

RL: The council, which we call the academic council, will certainly be established. We have shortlisted about ten personalities from the Czech Republic and abroad. However, we do not want to name them at this moment.

In one of your earlier statements, you mentioned that there would also be foreign "stars" at the school. Can you at least mention specific names in this case and indicate what role the stars will have at ARCHIP?

RL: We are counting on a foreign teacher to lead the fifth studio; furthermore, foreign teachers should participate in project critiques and also hold lectures. With some well-known architects who have given lectures or held exhibitions in Prague, Martin had discussions about our school at one time; plus, we have various permanent contacts abroad. However, we would rather not name specific names yet, as the school has only existed for a few weeks, and nothing is yet definitively agreed upon and planned... It is better to surprise than to boast with star names that ultimately might not come to fruition.

PP: However, for us, proper teachers who are already listed on the web are essential, and we believe they are among the best.

Currently, you have obtained accreditation for a bachelor's degree – how do you envision the application of your graduates?

RL: I will be very glad when as a practicing architect, I go to the office and find an employed architect there. We think that in many places in public administration, this profession with comprehensive education and a comprehensive view is lacking. Everything begins with the territorial and regulatory plan. It is still a field that seems to not exist. In our opinion, students should learn about its existence and meaning right from the start.

Regarding the extent of study, I will add that we want to apply for a follow-up master's program as soon as possible.

PP:Regarding employment, one could also talk about other areas: education – primary and secondary, other organizations such as heritage conservationists, nature protection, interest groups... Besides execution projects, architects can thus find application in a whole range of other fields. And this much earlier than is usually the case. Already at the level of strategic decision-making and investment considerations. Both in the private and public sectors.

From our perspective, the ideal scenario is that an investor comes to the architect and says: I need advice, to consult, to solve my housing needs. Not: I have a piece of land where I want a one-story family house of such and such square meters.

Thus, we want to shift the focus from the specific forms of buildings and their styles to the level that examines how architecture functions, what it serves, and for whom, and whether it truly benefits society. Because architecture itself is quite well conceived. The issue is whether and how it applies and presents itself toward the widest public and what real impact it has on shaping living space.

There is no overarching European legislation for the field. If we talk about urban planning and greater involvement of architects in offices, which can only be agreed upon, this raises the question: To what extent will the fact that the school is located in Prague influence the teaching of legislative-administrative processes? I mean, will students be familiarized with the Czech legislative environment given that your students will include foreigners from non-European countries?

RL: We have of course dealt with this question because each country has different legislation. However, urban planning will be led at the school by French engineer Anne Morriseau, who studied this distinct field. We must provide insight, but we will not go into details, precisely because our students will be international. In my opinion, these processes can be generalized.

PP: It’s about principles, defining problems. An example of how problems can be solved. The approach that works to improve urban space in Copenhagen can also be modified to work in Prague. Similarly, for instance, the problems of urbanization and suburbanization that the Third World is tackling have affected or still influence Europe as well. Within the bachelor's program, it's important to be aware of them. But we certainly do not aspire to teach legislation in detail. The school cannot substitute practice.

The commencement of classes in mid-October is not far off. Have you already thought about the semester assignment for your first students?

RL: We would like to assign only one theme for our five studios each time, for better comparison and mutual communication.

PP: Moreover, also for better defining the problem and more precise preparation of the topic. Analysis is often underestimated here. An internal competition should be created.

RL: In the future, I am in contact with, for example, the chief architect of Pardubice, where several interesting assignment opportunities are emerging. We will not shy away from ongoing architectural competitions either. However, for the first semester, we have chosen a theme that is distinctly Prague-oriented, which we also discussed with Václav Králíček from the Development Department of the Capital City. The Student Union of Charles University has developed an initiative and opened up the issue of strategic orientation of this institution until 2030. This concerns the urbanism of Prague and at the same time the theme of study; all our architectural schools are involved in the project – so for starters, this assignment seems ideal to us.

Thank you for the interview.

Kateřina Lopatová

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

27 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

90k?!

Thomas

27.05.10 02:25

pro talentované

Zbyněk Musil

28.05.10 10:44

díky za tu

Vích

28.05.10 12:27

re Thomas

vga

28.05.10 03:44

Co bych dal za to aby me učil Loukotová Gebrian či Palaščák

LM

28.05.10 05:43

show all comments

Related articles

0

01.08.2014 | Lecture: 4000 Years of Mexican Architecture, August 5, 2014

0

11.10.2011 | First public lecture at ARCHIP: Who invented the panelák?

15

11.01.2011 | Study architecture in Prague + get an ARCHIP scholarship

7

06.08.2010 | ARCHIP is launching preparatory courses

1

08.06.2010 | ARCHIP - introductory public presentation, Thursday, June 10.

0

26.05.2010 | Survey about the New School of Architecture