<Václav Odvárka - Objects of Mass Recreation>

|

diploma project — defended in June 2010

studio — Architecture I

studio leader — Prof. ak. arch. Jindřich Smetana

assistant — MgA. Josef Čančík

work consultant — Mgr. Cyril Říha, Ph.D.

work opponent — Doc. ing. arch. Zdeněk Jiran

In the Czech Republic, one often encounters an unpleasant disharmony between tourism or other ways of spending free time and the places where it occurs. We often encounter one common denominator. The original meaning of visiting and knowing these places has faded or completely changed. The subject of the diploma thesis was the architecture of this environment. How to further deal with preserved but outdated objects? Is it possible to integrate them into a natural, free tourism? Is it desirable to use them differently? What can they communicate to us? How can we connect to their/our immediate past?

The work focused on a rough exploration of the issues of capacity accommodation facilities in our country, searching for both historical and sociological connections, leading to the selection of a specific, problematic case and the proposal for its solution.

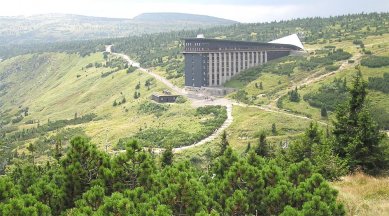

I ultimately chose Labská bouda as an exemplary yet specific problem. It has been facing significant existential problems for a long time and is heading towards definitive extinction. Just like many other buildings from the post-normalization period, Labská bouda has many opponents. Currently, the management of the Krkonošskoho National Park is at the center of resistance. The main arguments for removal are the disruption of the landscape and the fact that the building does not belong in the first zone of KRNAP. Labská bouda is one of the few interesting and distinctive architectural achievements that have emerged in the Krkonošskoho since 1929 (the Great Depression). In the proposal, I attempt to find another path than condemning it to definitive extinction.

The work is also intended as an appeal against hasty treatment of buildings from this era in post-communist society, where particularly during the 1990s there was a popularization of resistance to similar realizations. I consider it important to approach any heritage and our own history with as much consideration as possible.

Background — While in centers such as Harrachov, Špindlerův Mlýn and Pec pod Sněžkou, their inhabitants struggle with taming wild builders and designers, in the higher parts, some long-standing huts are increasingly failing. The most notable are the large ones, e.g., Sokolská bouda on Černá hora, Labská bouda at the source of the Elbe, or Petrova bouda above Špindlerův Mlýn, which was a significant architectural contribution at the turn of the 19th century and today represents an important monument in serious jeopardy. The origins of their problems can be traced to three basic interdependent points: energy management, accessibility, and capacity.

New Labská bouda — A mountain hotel designed by architect Zdeněk Řihák, completed in 1975 with a capacity of 160 beds, prepared for the influx of bus tours will find its place in the inhospitable yet picturesque peaks of the Krkonošsko hardly. In the design, I seek a way to update the program, reduce operational demands, and explore possible benefits that the building could provide in terms of nature conservation and harmonization with it. The contents of the traditional Krkonošsko hut serving tourists here are understood as a significant and meaningful starting point. It was never meant to be something detrimental to the mountains, but rather a useful element that allows visitors to have a gentle stay in the surroundings. At the same time, it should make people aware of the surrounding inhospitable world, which is nevertheless so attractive and related. Labská bouda also hides many other unusual possibilities for confronting the visitor, the building, the place, and history.

Form — Regardless of the question of whether such a type of building should have even been created here (it simply stands here), the building represents a manifestation of its time and a very specific assignment, but also a unique sensitivity of the architect and his ability to create a building that consciously communicates with its environment. All the steps I took in searching for the resulting form were guided by the effort to perceive the building as it is and what it naturally offers. My authorship is not based on the creation of new forms, but on discovering already existing ones hidden in the building.

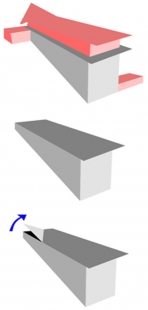

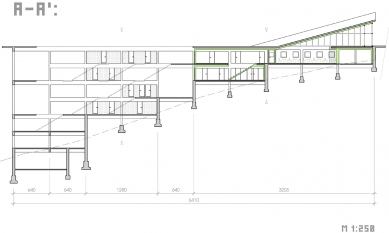

The basic component of the solution concept is the preservation of the existing building and its acknowledgment. At the same time, it is an effort for pragmatism and non-attachment to form, which led to the proposal to remove certain parts. I tried to synthesize both goals. The volume of the preserved mass in the proposal is reduced from nine to seven floors. The roof thus descends to the level of the existing parapet, which is experientially generous. It becomes a walkable terrace, extending from the slope into the open space of the Labské valley. In winter, snow accumulation is prevented here by prevailing and intense western winds. Other parts that I found expendable and propose to remove are “extensions” protruding beyond the main mass—a storage of light heating oils on the northern side at the ground level and garages at the level of the seventh floor at the entrance on the south.

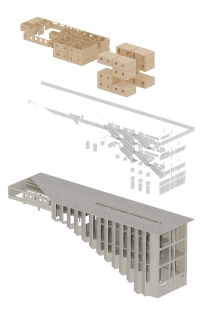

The remaining skeleton is then proposed to be stripped of non-load-bearing partitions and fillings, revitalized, and utilized as a landscape where a new story will unfold. This story will define itself against the building, but will also be dependent on it.

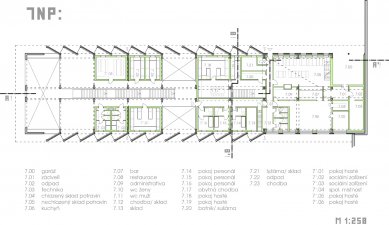

Program — The cleaned skeleton forms the basic chassis and backdrop for the proposed program. Activities within its interior can be imagined on two basic levels. Moving from the slope downward, the user's degree of "certainty" and perhaps predictability decreases. The first level – COMPACT INFILL includes a restaurant, sanitary facilities, part of the technical and operational background, a sauna, communal spaces, and the first type of accommodation in heated rooms. It is positioned closest to the slope. The second level – DISTRIBUTED INFILL allows for stay in the open structure of the building and accommodation in two additional types. The second type consists of unheated, insulated huts, a modified version of, for example, Tatra sheepfolds. The third type of accommodation is a bivouac. It is the least comfortable but carries its unique qualities. Places for pitching tents or simply lounging would be equipped with mats capable of partially insulating cold from the concrete while also being adapted for tent anchoring (modifications of Heraklit or industrial load mats). Camping or sleeping on a mat intertwines with the second type in the open structure of the building. Social facilities with a drying room and huts with "communal" seating are accessible to all.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

19 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

zajímavá cesta pro Labskou boudu

jirmac

13.07.10 07:08

Gratuluji k vyjjímečné práci - je vidět rozumné řešení !!

mk

13.07.10 11:03

!!

čmelda

14.07.10 12:02

mimořádná práce

petr jehlík

15.07.10 03:58

autorovi

kuzemenský

15.07.10 10:27

show all comments

Related articles

0

20.01.2012 | The mountain hut in the Krkonoš Mountains wants to be bought by the hut owner Holeček

0

17.08.2011 | The state has abandoned the plan to purchase the Labská bouda.

0

12.07.2010 | VŠUP - Theses 2010

0

12.07.2010 | Matěj Jakoubek – Jablonec nad Nisou

10

12.07.2010 | Jitka Mólerová – Completion of Old Town Square

16

12.07.2010 | Ida Čapounová - Countryside and Landscape