<Translation>Nondescript Magritte in an unassuming house created surrealist pearls</Translation>

|

Magritte (1898-1967), like the chansonnier Jacques Brel, cyclist Eddy Merckx, or writer Georges Simenon, belongs to the pantheon of several internationally famous Belgians that this small country prides itself on. Many of his paintings, such as Treachery of Images depicting a pipe with the words Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe), have penetrated public awareness not only among art historians.

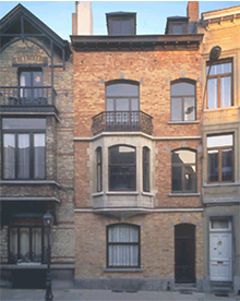

Magritte was born in Lessines, left school in 1916, and began studying painting in Brussels. In the late 1920s, he lived in Paris, where he befriended the surrealists around André Breton for about three years but never fully agreed with them. When he lost his job in Paris, he returned to Brussels in 1930 and settled in a ground-floor apartment at 135 Esseghem Street, where his museum is located today.

At that time, only a few insiders knew him, but by the time he left the house 24 years later, he was one of the most famous Belgian painters. He painted a number of masterpieces here, such as L'empire des lumieres (The Empire of Light) and Golconda, which are unmistakable not only for their vivid and bright colors but also for their mysterious and unexpected combinations, playfulness, and wit.

Although his paintings were nonconformist, Magritte led an outwardly unremarkable life with his wife Georgette. He deliberately adopted the image of a calm man living a regular life as a childless bourgeois, wrote art historian Patrick Roegiers.

He diverged from most surrealists in his views on psychoanalysis and rejected psychoanalytic interpretations of his paintings. They are not about dreams and the subconscious, he insisted, but about mystery and enigma. "They mean nothing, because mystery also means nothing; it is unknowable," he claimed.

Magritte's apartment, at first glance, also corresponds to the image of a calm, inconspicuous middle-class life, perhaps with the exception of the walls painted in bright pastel colors. An unprepared visitor expecting surreal eccentricities will only be delighted when they see a stuffed dog on the carpet. At that time, it was common for owners - not just surrealists - to have their dog stuffed, though it cools the enthusiasm of the guide.

But a closer look will richly reward surrealist fans for their long journey to the outskirts of Brussels. The house is filled with objects that inspired Magritte's paintings. Already at the entrance stands a streetlamp from the series of canvases Kingdom of Light. In the "living room", that is, the salon, there is a sliding window behind which, in Magritte's paintings, the other side of the street is not visible, but rather fictional landscapes. And the fireplace seems to have popped out of the painting La durée poignardée (The Choke of Time), from which a locomotive emerges. In other works, stairs appear in the hallway or a wardrobe with a suitcase in the bedroom.

Magritte painted most of his canvases in a small room off the kitchen, usually with the curtains drawn in artificial light, even though he had a bright studio set up in the former gazebo in the garden. There, however, he only worked on graphics and advertising, which supported him for a long time.

As a painter, he gained fame only in the 1950s. At that time, his agent became the American Alexander Iolas, who arranged major exhibitions for him in New York. Magritte began to do well financially and decided to move in 1954 from Esseghem Street - but only a few kilometers further to another Brussels district, Schaerbeek.

But even there, until his death, he led an equally calm existence as a "bourgeois" as well as a surrealist. According to Roegiers, he was "a logician of imagination and a methodical creator," but also a "bon vivant, mystifier, and incorrigible joker." And he clearly took pride in this paradox. You will never know who I am, he said of himself with a laugh.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment