To the exhibition Restless Architecture at MAXXI

Publisher

Petr Šmídek

02.04.2025 09:00

Petr Šmídek

02.04.2025 09:00

Italy

Rome

Elizabeth Diller

Ricardo Scofidio

Charles Renfro

diller scofidio + renfro

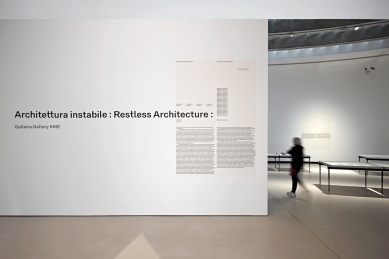

Less than two weeks before the end of the exhibition Architettura instabile (Restless Architecture) at the MAXXI museum in Rome, came the sad news from overseas about the passing of one of the curators, the American architect Ricardo Scofidio, who died at the age of 89. Together with his wife Elizabeth Diller, he founded an interdisciplinary studio in the late 1970s that incorporated new media and movement into architecture. Ricardo Scofidio initially pursued an academic career as a collaborator of John Hejduk, occasionally designing short-term installations or stage design. When he met Elizabeth Diller at the Cooper Union in New York, they began to focus on more permanent architectural designs. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R) managed to compellingly interpret scientific research. Transitory events under their direction always leave strong impressions. They had previously exhibited intangible things in inventive ways, such as scents or engagingly presenting something as mundane as a lawn.

The latest exhibition by DS+R focuses on the ephemeral and unstable aspects of architecture. The museum building itself, designed by Zaha Hadid, with its undulating shapes, vaguely resembles some Baroque monuments, but ultimately does not strive too hard to fit into the Roman environment. Exhibiting in elongated halls with partially slanted floors and walls poses a challenge for any curator, confirming the words of the German painter Markus Lüpertz, that “today's museums try to be more artistic than the art within them.”

DS+R are not appearing at the Roman museum for the first time. In 2010, they presented the installation Mural at the inaugural exhibition Spazio at MAXXI. The work of Elizabeth Diller was also featured in the exhibition Good News. Women in Architecture in 2022. DS+R did not choose Rome for their presentation of restless architecture by chance. It is here that more than two thousand years ago the theorist Marcus Vitruvius Pollio worked, which is also pointed out by the new director of MAXXI, Lorenza Baroncelli, in her introductory text.

Vitruvius, in his Ten Books on Architecture, concluded that buildings should exhibit three fundamental qualities: durability, functionality, and beauty (firmitas, utilitas et venustas). The Vitruvian formula is also depicted on the Pritzker Prize for architecture, awarded by the Hyatt Foundation in Chicago since 1979. Although DS+R have not received the Pritzker Prize, their work has been recognized by many other institutions worldwide, including the Honorary Medal of the American Academy in Rome in 2013, the Lawrence Israel Prize in 2012, the Jane Drew Prize in 2019, and the Wolf Prize in Arts in 2022. In the Roman exhibition, they playfully challenge Vitruvius's theory. For a comprehensive picture, it should be mentioned that Vitruvius's theoretical work does not only address architecture; the ninth volume focuses on the movement of celestial bodies and methods of measuring time, and in the tenth book, he extensively analyzes various machines.

Vitruvius's first requirement for strength (stability, durability) is negated by the title of the exhibition dealing with examples of unstable architecture, which lacks solid foundations and is in constant motion. The second requirement of functionality by Vitruvius was mainly exaggerated by modernists in the last century, but as we know, the leaking roof did not trouble the leading figure of Le Corbusier. As the third, Vitruvius mentioned beauty (grace), which everyone perceives subjectively, and what is generally liked can be considered average. Any debate about what can no longer be considered architecture is left to Hansi Hollein (the Pritzker Prize winner from 1985), who provocatively stated in his text from 1967 that "everyone is an architect and everything is architecture." A short film by Hollein Mobile Office (1967) is projected on the entrance wall, which most of us know from photographs as an inflated capsule in a meadow with an architect working inside.

After viewing the film, you connect the image with the sarcastic tone of Hollein's voice and the sophistication that recalls the performance of another Austrian studio Coop Himmelb(l)au, which is showcasing an unrealized project Cloud I (1968). Rather than complex theories, the accompanying texts by Coop Himmelb(l)au come across with the punchiness of a rock song not written on paper but recorded on a vinyl record: "We sit on the plane and think of whiskey. The sun in our eyes and clouds on our shirts. Rolling Stones in our ears. Another city ahead of us. Vienna behind us."

Before visiting the exhibition Restless Architecture, we expected it to be a retrospective exhibition of DS+R's work combined with an extensive nearly 800-page monograph published simultaneously by Phaidon in New York. Ultimately, DS+R included only one of their realizations, The Shed (2019), among the exhibits, and the other was their intervention directly into the exhibition space, where a pair of semi-transparent partitions moved through. These textiles constantly transformed the linear exhibition space, creating backgrounds for individual exhibits and enclosing temporary projection rooms where short documentary blocks were screened. An analysis of movement in architecture even before the invention of cinematography would produce a comprehensive publication or another separate exhibition. DS+R selected several representatives primarily from the 20th century from a long timeline. In front of the museum, one of the rescued prefabricated units from the Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo (K. Kurokawa, 1972), which was demolished three years ago, was installed. Another exhibit at full scale was the ornamental mechanical window of the Arab Institute in Paris (J. Nouvel, 1987). An example of global interconnectedness was the temporary pavilion Prada Transformer (2009) by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas for the Italian clothing brand Prada, created for a fashion show in the South Korean capital. In addition to the translucent model, a time-lapse film had to be viewed for a complete understanding, where the steel structure rotates with the help of four giant cranes. It was not just about a change in the internal installation but an overall feeling of uncertainty that the walls or ceiling could transform into the floor in the next moment and start serving a completely different function.

A pleasing piece of news for Czech visitors was that two realizations from interwar Czechoslovakia appeared at the exhibition. Drawings, contemporary photographs, and new video documents captured the mobile office in the Baťa skyscraper in Zlín (V. Karfík, 1939) and the mechanical card index in the building of the Czech Social Security Administration in Prague's Smíchov (J. Gillar, 1936).

If the curators had more exhibition space and time for exploration, even the contemporary Czech scene would have much to offer. For instance, it is worth mentioning the machine for making ice huts (mjölk, 2011), which relates to the Liberec Mašinists and can stand up to international comparison. The topic is certainly not exhausted, and in the future, someone else will continue from DS+R.

More information >

The latest exhibition by DS+R focuses on the ephemeral and unstable aspects of architecture. The museum building itself, designed by Zaha Hadid, with its undulating shapes, vaguely resembles some Baroque monuments, but ultimately does not strive too hard to fit into the Roman environment. Exhibiting in elongated halls with partially slanted floors and walls poses a challenge for any curator, confirming the words of the German painter Markus Lüpertz, that “today's museums try to be more artistic than the art within them.”

DS+R are not appearing at the Roman museum for the first time. In 2010, they presented the installation Mural at the inaugural exhibition Spazio at MAXXI. The work of Elizabeth Diller was also featured in the exhibition Good News. Women in Architecture in 2022. DS+R did not choose Rome for their presentation of restless architecture by chance. It is here that more than two thousand years ago the theorist Marcus Vitruvius Pollio worked, which is also pointed out by the new director of MAXXI, Lorenza Baroncelli, in her introductory text.

Vitruvius, in his Ten Books on Architecture, concluded that buildings should exhibit three fundamental qualities: durability, functionality, and beauty (firmitas, utilitas et venustas). The Vitruvian formula is also depicted on the Pritzker Prize for architecture, awarded by the Hyatt Foundation in Chicago since 1979. Although DS+R have not received the Pritzker Prize, their work has been recognized by many other institutions worldwide, including the Honorary Medal of the American Academy in Rome in 2013, the Lawrence Israel Prize in 2012, the Jane Drew Prize in 2019, and the Wolf Prize in Arts in 2022. In the Roman exhibition, they playfully challenge Vitruvius's theory. For a comprehensive picture, it should be mentioned that Vitruvius's theoretical work does not only address architecture; the ninth volume focuses on the movement of celestial bodies and methods of measuring time, and in the tenth book, he extensively analyzes various machines.

Vitruvius's first requirement for strength (stability, durability) is negated by the title of the exhibition dealing with examples of unstable architecture, which lacks solid foundations and is in constant motion. The second requirement of functionality by Vitruvius was mainly exaggerated by modernists in the last century, but as we know, the leaking roof did not trouble the leading figure of Le Corbusier. As the third, Vitruvius mentioned beauty (grace), which everyone perceives subjectively, and what is generally liked can be considered average. Any debate about what can no longer be considered architecture is left to Hansi Hollein (the Pritzker Prize winner from 1985), who provocatively stated in his text from 1967 that "everyone is an architect and everything is architecture." A short film by Hollein Mobile Office (1967) is projected on the entrance wall, which most of us know from photographs as an inflated capsule in a meadow with an architect working inside.

After viewing the film, you connect the image with the sarcastic tone of Hollein's voice and the sophistication that recalls the performance of another Austrian studio Coop Himmelb(l)au, which is showcasing an unrealized project Cloud I (1968). Rather than complex theories, the accompanying texts by Coop Himmelb(l)au come across with the punchiness of a rock song not written on paper but recorded on a vinyl record: "We sit on the plane and think of whiskey. The sun in our eyes and clouds on our shirts. Rolling Stones in our ears. Another city ahead of us. Vienna behind us."

Before visiting the exhibition Restless Architecture, we expected it to be a retrospective exhibition of DS+R's work combined with an extensive nearly 800-page monograph published simultaneously by Phaidon in New York. Ultimately, DS+R included only one of their realizations, The Shed (2019), among the exhibits, and the other was their intervention directly into the exhibition space, where a pair of semi-transparent partitions moved through. These textiles constantly transformed the linear exhibition space, creating backgrounds for individual exhibits and enclosing temporary projection rooms where short documentary blocks were screened. An analysis of movement in architecture even before the invention of cinematography would produce a comprehensive publication or another separate exhibition. DS+R selected several representatives primarily from the 20th century from a long timeline. In front of the museum, one of the rescued prefabricated units from the Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo (K. Kurokawa, 1972), which was demolished three years ago, was installed. Another exhibit at full scale was the ornamental mechanical window of the Arab Institute in Paris (J. Nouvel, 1987). An example of global interconnectedness was the temporary pavilion Prada Transformer (2009) by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas for the Italian clothing brand Prada, created for a fashion show in the South Korean capital. In addition to the translucent model, a time-lapse film had to be viewed for a complete understanding, where the steel structure rotates with the help of four giant cranes. It was not just about a change in the internal installation but an overall feeling of uncertainty that the walls or ceiling could transform into the floor in the next moment and start serving a completely different function.

A pleasing piece of news for Czech visitors was that two realizations from interwar Czechoslovakia appeared at the exhibition. Drawings, contemporary photographs, and new video documents captured the mobile office in the Baťa skyscraper in Zlín (V. Karfík, 1939) and the mechanical card index in the building of the Czech Social Security Administration in Prague's Smíchov (J. Gillar, 1936).

If the curators had more exhibition space and time for exploration, even the contemporary Czech scene would have much to offer. For instance, it is worth mentioning the machine for making ice huts (mjölk, 2011), which relates to the Liberec Mašinists and can stand up to international comparison. The topic is certainly not exhausted, and in the future, someone else will continue from DS+R.

More information >

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment