House K

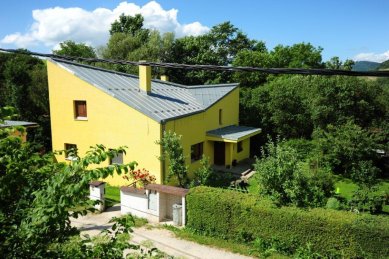

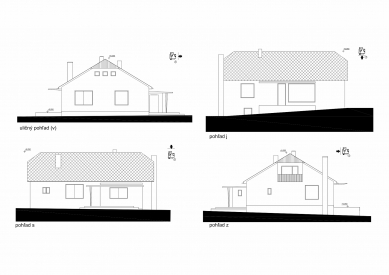

Technically, the building involves the removal and replacement of the structurally and functionally inadequate original roofing and ceiling of the family house. The original house was created decades ago by reconstructing and extending another structure. In the original building, there were structurally, spatially, and shape-wise several houses as a result of the heterogeneity of opinions of its builders expressed at different times in various forms.

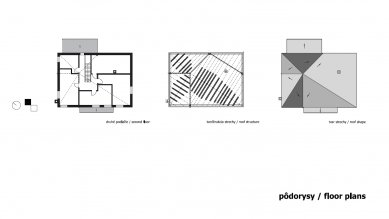

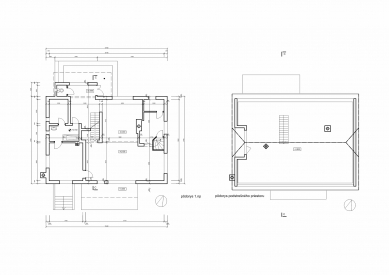

The requirement was to create such roofing that would allow for the organization of living functions in the created space - sleeping, living for three children, and hygiene, using a wooden truss structure.

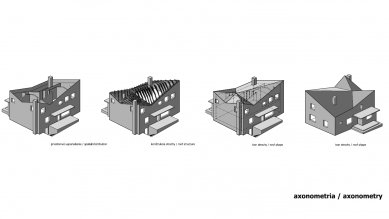

The roofing solution did not arise independently as an author's decision referencing tradition or intuition, but is the result of mixing and balancing the chosen parameters. In addition to parameters arising from function (number of people, areas, volumes, heights), the shaping of the roof involved parameters of the surroundings, orientation, construction, materials, and connections.

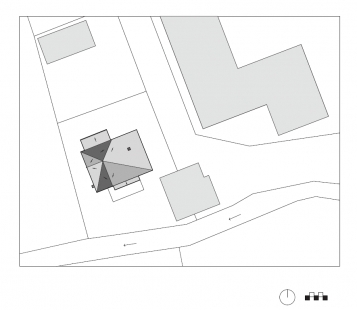

The function/person parameter defined the necessary number and size ratios of the spaces, and at the same time established the minimally acceptable heights of the sloped planes. The surrounding parameter included the relationship of the roofing to the elevated part of the property, the largest part of which continues on the southern side of the house bordering a meadow, a stream, and part of a hill. The goal of manipulating these parameters was to maximize the relationship of the roofing to the land. The orientation parameter accounted for the relationship of the house to the sun's path. The aim of manipulating this parameter was to minimize overheating of the interior of the roofing by the sun in summer while maintaining good lighting conditions. The construction and materials parameter limited the spans and slopes of the roofing planes according to maximum and optimal conditions so that a wooden truss and metal roofing could be used. The connection parameter took into account the existing links between the old house and the new roofing. Its role was to minimize changes in the old part by utilizing the already existing stair layout and networks for water and sewage.

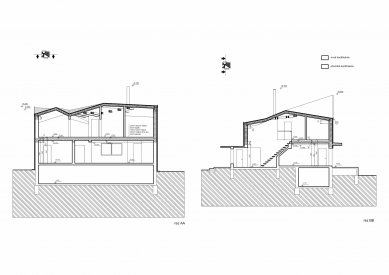

The surrounding parameter positioned the rooms so that they had the closest and best contact with this environment - at the edge of the southern side of the house. Ensuring good visual contact with the surroundings and the requirement to prevent interior overheating, along with the requirement for established minimum heights, excluded the use of roof windows and raised the edges of the roof and base on the southern and western sides above the visual contact level of a standing person. The positioning of hygiene facilities on the edge of the western and northern sides of the house was conditioned by the possibilities of the simplest connection to existing networks. The spatial solution of hygiene follows the logic of room solutions, thus raising the edge of the roof. The northern edge of the roof was kept at the lowest level possible so that the roofing plane could avoid sunlight and ensure a slope for drainage. The function and construction parameters sliced the plane at the junctions of the interior spaces and transformed the heights above these connections. The edges of the roof plane at the room-to-room connections were deformed so that a wooden rafter and purlin construction with steel beams in the valleys could be used, the heights of the roof plane at the room-to-exterior connections rise and fall - adapting to the internal logic of the roofing construction over individual spaces and the distribution of functions. Heights continuously change in space and allow for "accommodation" of various functions according to optimal or maximum requirements. The spaces have two differently sloped roofing planes - a "cold" and a "warm" part of the roof.

The entire roofing structure is placed on a peripheral reinforced concrete ring and does not intrude into the interior space with any other elements except for the tie rod - purlins.

Later, during the communication process with the client, the interior space continued to differentiate. On the northern side, in the less accessible area, a storage room was created, and a large living space was divided at the request of the children.

The dome is one of the first realizations of the atelier in Tisovec. The original assignment, which aimed to restore the gabled roof of a single-storey house after several reconstructions and build an attic, changed thanks to the verification of the parametric method into an extension of the family house in a hybrid incomplete multi-storey and simultaneously not purely roofing landscape. The originally simple task, which was almost always technologically solved in the heterogeneous and essentially non-architectural environment of Tisovec directly by referencing traditional materials and methods, and shape-wise by pointing out the context of gable, mansard, and flat roofs, gained new forms of complexity by incorporating additional aspects and contexts. The architect has always been faced with the basic task of how to reconcile multifaceted determinations into a meaningful whole, but parametric design also modifies the position of the architect in this process and changes our perceptions of architecture. Architecture ultimately ceases to comply with established rules and aesthetic criteria and becomes primarily a research endeavor in which the computer and its capabilities intervene along with the client.

According to their own words, the architects worked with a multitude of parameters, which they classified into several groups: program or functional content, contact with the environment, orientation or energy efficiency, construction and materials, connection with the existing building, user participation. Some parameters from these groups were defined clearly, such as the wooden truss and metal roofing, while others were more variable, such as energy efficiency and orientation to the cardinal points, and some were presumably parameterized rather complexly, as in the case of participation. The parameters were optimized in the design process to acquire specific weights. Their influence was simultaneously initiating and limiting: parameters from the orientation and energy efficiency group excluded the attic and windows in the roof but simultaneously stimulated the raising of the edges of the roof on the western and southern sides. The parameters of materials and construction in synergy with the parameters of participation caused that the interaction of all groups did not lead to wavy complicated surfaces, but to faceting of roofing planes, and thus also the outer walls and ceilings or soffits. In this complex process of parametric design, the architects did determine specific weights (the north-south orientation could not be circumvented), but the final shaping was no longer influenced by them, but rather controlled and verified in retrospect. Therefore, their position is ambivalent: on one hand, they stand outside the design process, on the other hand, they can intervene in its course as one of its parameters.

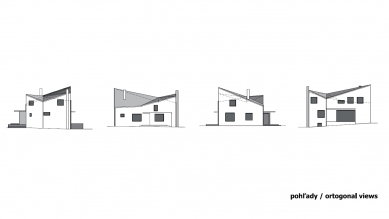

The outcome of the parametric design method can paradoxically result in stylistic or retro-stylistic allusions (the extension and roof is more cubist than cubism), but the shape and spatial distribution and division are not the result of either eternal architectural logic or fleeting fashion. On the contrary, they are the result of orchestrating multifaceted requirements, from which even an originally small house can gain an additional floor and a large roof. Under it hides a wavy flowing space, one possible configuration of which is fan-shaped segmentation of L-shapes around vertical communication. Ultimately, the new house is a house of many faces seemingly reacting ad-hoc to the aforementioned heterogeneous environment.

The requirement was to create such roofing that would allow for the organization of living functions in the created space - sleeping, living for three children, and hygiene, using a wooden truss structure.

The roofing solution did not arise independently as an author's decision referencing tradition or intuition, but is the result of mixing and balancing the chosen parameters. In addition to parameters arising from function (number of people, areas, volumes, heights), the shaping of the roof involved parameters of the surroundings, orientation, construction, materials, and connections.

The function/person parameter defined the necessary number and size ratios of the spaces, and at the same time established the minimally acceptable heights of the sloped planes. The surrounding parameter included the relationship of the roofing to the elevated part of the property, the largest part of which continues on the southern side of the house bordering a meadow, a stream, and part of a hill. The goal of manipulating these parameters was to maximize the relationship of the roofing to the land. The orientation parameter accounted for the relationship of the house to the sun's path. The aim of manipulating this parameter was to minimize overheating of the interior of the roofing by the sun in summer while maintaining good lighting conditions. The construction and materials parameter limited the spans and slopes of the roofing planes according to maximum and optimal conditions so that a wooden truss and metal roofing could be used. The connection parameter took into account the existing links between the old house and the new roofing. Its role was to minimize changes in the old part by utilizing the already existing stair layout and networks for water and sewage.

The surrounding parameter positioned the rooms so that they had the closest and best contact with this environment - at the edge of the southern side of the house. Ensuring good visual contact with the surroundings and the requirement to prevent interior overheating, along with the requirement for established minimum heights, excluded the use of roof windows and raised the edges of the roof and base on the southern and western sides above the visual contact level of a standing person. The positioning of hygiene facilities on the edge of the western and northern sides of the house was conditioned by the possibilities of the simplest connection to existing networks. The spatial solution of hygiene follows the logic of room solutions, thus raising the edge of the roof. The northern edge of the roof was kept at the lowest level possible so that the roofing plane could avoid sunlight and ensure a slope for drainage. The function and construction parameters sliced the plane at the junctions of the interior spaces and transformed the heights above these connections. The edges of the roof plane at the room-to-room connections were deformed so that a wooden rafter and purlin construction with steel beams in the valleys could be used, the heights of the roof plane at the room-to-exterior connections rise and fall - adapting to the internal logic of the roofing construction over individual spaces and the distribution of functions. Heights continuously change in space and allow for "accommodation" of various functions according to optimal or maximum requirements. The spaces have two differently sloped roofing planes - a "cold" and a "warm" part of the roof.

The entire roofing structure is placed on a peripheral reinforced concrete ring and does not intrude into the interior space with any other elements except for the tie rod - purlins.

Later, during the communication process with the client, the interior space continued to differentiate. On the northern side, in the less accessible area, a storage room was created, and a large living space was divided at the request of the children.

A Small House with a Large Roof

The bbha or n/a atelier is formed by two educators from the Department of Architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bratislava. Benjamin Bradňanský is a graduate of the Faculty of Architecture at STU and currently leads one of the three ateliers of the department alongside Imro Vašek and Ján Bahna. Vít Halada completed his master's and doctoral studies in architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts. Both architects were connected not only by joint competition projects with the loosely grouped IVA and collaboration with foreign firms but primarily by an interest in contemporary design methods, the results of which could be observed for several semesters both in the examinations of student work as well as in workshops and seminars at home and abroad.The dome is one of the first realizations of the atelier in Tisovec. The original assignment, which aimed to restore the gabled roof of a single-storey house after several reconstructions and build an attic, changed thanks to the verification of the parametric method into an extension of the family house in a hybrid incomplete multi-storey and simultaneously not purely roofing landscape. The originally simple task, which was almost always technologically solved in the heterogeneous and essentially non-architectural environment of Tisovec directly by referencing traditional materials and methods, and shape-wise by pointing out the context of gable, mansard, and flat roofs, gained new forms of complexity by incorporating additional aspects and contexts. The architect has always been faced with the basic task of how to reconcile multifaceted determinations into a meaningful whole, but parametric design also modifies the position of the architect in this process and changes our perceptions of architecture. Architecture ultimately ceases to comply with established rules and aesthetic criteria and becomes primarily a research endeavor in which the computer and its capabilities intervene along with the client.

According to their own words, the architects worked with a multitude of parameters, which they classified into several groups: program or functional content, contact with the environment, orientation or energy efficiency, construction and materials, connection with the existing building, user participation. Some parameters from these groups were defined clearly, such as the wooden truss and metal roofing, while others were more variable, such as energy efficiency and orientation to the cardinal points, and some were presumably parameterized rather complexly, as in the case of participation. The parameters were optimized in the design process to acquire specific weights. Their influence was simultaneously initiating and limiting: parameters from the orientation and energy efficiency group excluded the attic and windows in the roof but simultaneously stimulated the raising of the edges of the roof on the western and southern sides. The parameters of materials and construction in synergy with the parameters of participation caused that the interaction of all groups did not lead to wavy complicated surfaces, but to faceting of roofing planes, and thus also the outer walls and ceilings or soffits. In this complex process of parametric design, the architects did determine specific weights (the north-south orientation could not be circumvented), but the final shaping was no longer influenced by them, but rather controlled and verified in retrospect. Therefore, their position is ambivalent: on one hand, they stand outside the design process, on the other hand, they can intervene in its course as one of its parameters.

The outcome of the parametric design method can paradoxically result in stylistic or retro-stylistic allusions (the extension and roof is more cubist than cubism), but the shape and spatial distribution and division are not the result of either eternal architectural logic or fleeting fashion. On the contrary, they are the result of orchestrating multifaceted requirements, from which even an originally small house can gain an additional floor and a large roof. Under it hides a wavy flowing space, one possible configuration of which is fan-shaped segmentation of L-shapes around vertical communication. Ultimately, the new house is a house of many faces seemingly reacting ad-hoc to the aforementioned heterogeneous environment.

Marian Zervan (written for ARCH magazine 12/2008)

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

3 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

krytina

Matúš Pajor

27.04.11 01:35

Po prohlédnutí fotek mne můj vlasní cynizmus ponoukl,

gallina-scripsit

27.04.11 04:47

divné

šárka

28.04.11 07:20

show all comments