Interview with Odile Decq Odile Decq is a prominent architect known for her bold designs and innovative approach to architecture. In this interview, she shares her insights on the future of architecture, the importance of creativity, and her experiences as a female leader in a male-dominated field. <h2>Career Journey</h2> Decq reflects on her career journey, discussing the challenges she faced and the triumphs that have shaped her work. She emphasizes the significance of perseverance and the drive to break boundaries in architectural design. <h2>Creative Process</h2> In describing her creative process, Decq highlights the importance of collaboration and experimentation. She believes that architecture should push limits and challenge traditional norms. <h2>Future of Architecture</h2> Looking ahead, Decq shares her vision for the future of architecture, focusing on sustainability, technological advancements, and the need for inclusivity in design.

Interview with the Europe Lead Architect and Educator

Source

Marie Davidová, Collaborative Collective

Marie Davidová, Collaborative Collective

Publisher

Petr Šmídek

25.04.2018 06:55

Petr Šmídek

25.04.2018 06:55

Czech Republic

Ostrava

Odile Decq

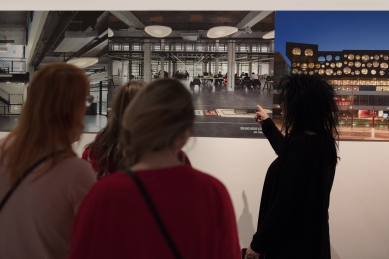

On the occasion of the lecture and the opening of the Horizons exhibition by French architect Odile Decq at the House of Art of the Gallery of Fine Arts in Ostrava, an interview was conducted, prepared for archiweb.cz by Marie Davidová. The Horizons exhibition, organized by the Architecture Cabinet as part of the 10th edition of the international festival of architecture, design, and art Archikulura 2018, can be viewed at the House of Art in Ostrava until June 3, 2018.

Odile Decq Will Show You Horizons!

Marie Davidová & Odile Decq

The Cabinet of Architecture had the pleasure of hosting Europe's leading architect’s visit and guest lecture on the occasion of her exhibition at the Gallery of Fine Arts in Ostrava that they organized within their annual, this year’s Tenth International Festival of Architecture, Design, and Art: the Archikulura 2018. Please consider this interview as both your life motivation and as a motivation for your visit to her exhibition HORIZONS, which lasts until June 3, 2018. Marie Davidová, who brings you the following unique interview, was there for the opening and the lecture, representing the Archiweb magazine. The steel queen meets the wooden queen and they discuss horizons!

MD: First, I need to warn you that I am neither a professional journalist nor a theoretician. I perform research by design and therefore I generate theory through experimental practice and also work with education. Therefore, I will be rather asking questions and will wonder based on my personal experience raised and/or motivated by your work and experience.

Did you experience any gender discrimination when starting your career and how do you experience it now?

OD: When I started my career, I was coming to many meetings with a lot of men and I was always asked: Oh, can you take notes? I said no, I am the architect. Can someone of the men take notes? I always had to assert the condition that I am the architect, not a secretary. Often they asked why you are not working in an architect’s office, meaning a man. I said because I am the architect. I received many comments like that until ten years ago or so. Now it is less, even if we still have some sometimes.

When I was starting, I had a feeling of having to prove twice that I am able to do the work in order to get a commission. And I discovered that I have to be much more experienced (than male architects) in terms of what I want to achieve. There was a big distrust in female architects. If you look at the projects that women are achieving today, they are not very big projects but they achieved a lot of them. There is still not equity in architecture.

MD: Personally, do you think there is progress through building your name and/or any progress through society development over that time?

OD: I think this is both. Now people know who I am and they are used to seeing my name. At the same time, society has changed in many countries a little bit, not a lot. There is still discrimination in terms of selection for competitions, in terms of the possibility to reach certain projects. In addition, I have often seen that the problem does not come from us. Because we know we are women, we know that we are architects, we know we are efficient and capable and we have the capacity to do it, and we are able to discuss with men as equals. However, men do not always want to give us this possibility. The initial problem does not come from us but from men.

MD: Is the situation better or worse at the academy or in practice?

OD: In the academy, there are more and more female deans at many places now. So, I think in the end it will change. In terms of teaching, there is no equality. There are not enough women. However, it is changing step by step. Because there are many countries discussing this problem. In practice, there is some progress still to be made.

MD: You founded your own architectural school, the Confluence Institute for Innovation and Creative Strategies in Architecture, in 2014 after being head of École Spéciale d’Architecture in Paris for five years due to disagreements at the place. Today science claims that the academy is one of the most psychopathic environments of all. Was that the reason for it? Alternatively, can you relate to it at all?

OD: Maybe because of competition among people. The problem was that I changed a lot at the school and in the end, the previous teachers said that it was enough. They had a feeling I would push them away. Therefore, because they wanted to protect themselves, they started to be very hard with me. And in the end, they succeeded in infiltrating the council making it difficult for me to continue. This is why I left the school.

MD: So, in a way, you have reached the glass ceiling.

OD: Yes, in a way. I was changing the idea of what an architectural school is. At the beginning, they were shocked but thought, why not. Then they said this is not what they wanted. This was the reason I launched my own school of architecture.

MD: What is personally the most important relation for you between the academy and practice? Is it an enriching feedback loop?

OD: First, I think most of the teachers have to be practitioners. At many universities, the academy is not allowed to practice. I find it very bizarre. Though some practitioners cannot teach and some teachers are not good practitioners, we have to have mixed possibilities. We need to offer diverse perspectives and points of view to students. They can join academia, they can join practice, become entrepreneurs… They can become who they want. This is why we have to employ a mixture in the school. Often, when I was teaching, what I felt in the morning was energetic in the evening. Going to the school was giving me energy, nourishing my mind, and I was trying to nourish the minds of my students. The largest happiness I experienced was when one of my students succeeded in doing something he believed he could not do. Enjoying his gaze at that moment was absolutely the most important for me. When you are a teacher in architecture, I sometimes think that we are not teaching the students something, we only need to help them go forward, to understand what they learn, and how to build themselves. The best satisfaction comes when you discover that your student has discovered who they are, what they want to do, and that they achieve that. I do not want them to repeat what I am doing. I am sure they will not be the same architects as I am. I am not interested in giving them the option to do what I am doing. They have to build their own way. This is important for me.

MD: Let us get to the discussion on confluence. You have stated that architects are special in problem-solving. Do you mean the profession that is trained to handle transdisciplinarity? Moreover, is it really the case of today’s practice? Architecture has been, to a certain degree, an interdisciplinary profession for a long time. However, this is a very different situation than transdisciplinary design process.

OD: I strongly believe that the world is different today than it was before. It is especially different because of the digital world, the possibility of the new tools that we have. Because of that, we need to reinvent and rethink how we educate and practice in the future. I do not know how my students will practice in the future. They have to invent their own ways of doing it. The most important aspect of interdisciplinary for me is the fact that we can nourish the field of architecture with all the other disciplines. When we are facing a problem in architecture, we have to convene all the other disciplines such as sociology, philosophy, art, economy, geography, and so on. You have to be able to synthesize that. Therefore, you have to be able to understand how these disciplines nourish your own ideas and your own possibilities to act. Thanks to that, we are very particular. Because this education gives you strategic tools you are not even realizing. This is why I believe that architects, especially, can help the world more than when they only design buildings. By helping the world, I mean acting, helping communities, helping cities, helping countries, helping companies. Because the way of thinking in architecture is peculiar due to complex situations leading to synthesis and proposals across different scales. The way we proceed is specific and unique. We need to give the students the consciousness of that specificity and the ability to do what they want.

MD: You talk about the redefinition of the architectural profession. Beth Sanders claims that this and other professions have transformed into other, more actual, professions. My wonder is, with the transdisciplinary perspective, whether we should not redefine the professions into fields of interest and totally forget such kind of differentiation.

OD: I do not know. I think if you look at schools of architecture, transdisciplinarity comes only with environment, building construction, and sociology sometimes. However, not every school is thinking about sociology, about art, about philosophy, about the way of thinking the world is enacted. This is why I always say that I am more interested in architecture than in architects. Architect is just a profession. I do not care how to define this profession because for me, architecture is what is important.

MD: You have stated that “The form of a building is really the end of a process.” – Isn’t it when the process starts?

OD: No, I also think that for me it is when the process starts. The form is an important thing. That is what I meant when I said that.

MD: OK, then I misunderstood this statement. I found the confusion between this statement and what one of your students stated that she is actually designing for experience. Building experiences means that when the experience is performed the process starts – not ends to me.

OD: She was doing research on surface, exactly as you do, a 3D printing textile. She managed to find a way to understand how she can build with it. Through that process of experimenting with this little object that was printed, she discovered what she could do. This is learning by doing.

She was like that. However, my students are not myself. For me, the form often comes at the end. Because I am not interested in designing the form and filling it. I prefer to work in a very experimental way and wonder what kind of experiences you can have.

MD: OK, I initially fully misunderstood this sentence. Because I was thinking that you mean that you build the house and then, when the real performance takes place for you the process ends.

OD: No, no.

MD: I love this discussion. The last three questions thematically lead to the topic of your exhibition: The ‘Horizons that cannot be reached.’ This topic is supposed to exhibit the experience – the endless process of becoming the building – its performance. Can you talk more about your personal experience of the exhibited projects?

OD: These nine projects? What do you mean by my personal experience?

MD: You design the house and then you build it. For me, I tend to visit these buildings or any other built stuff. I tend to observe what is happening there.

OD: For me, I do not feel like that. For me, my buildings have their own personal life after me. I cannot control a hundred percent of their evolution. I say that but at the same time, it sounds strange when my first big project, which was a bank, was planned to be destroyed three years ago, I reacted. It did not come from me but from my surroundings. They convinced me that I couldn’t let them tear it down. I had to fight. I fought and it has been saved. Now it will be renovated for another use. It was a bank and now it will be a school for building constructors. I like this idea. So, at the same time I control what the other architect is doing and he is not allowed to modify my façades. However, in the interior, they can do whatever they want because it was an open space building. I have to admit that every time I pass this region, I come to look at this building. Nevertheless, it is not like this with all my buildings. To the restaurant I built, I was coming for lunch or dinner when it was built but not so much now anymore. I do not have time for that. There is a certain time to let the project go, and for that time, I keep going there. Yes, that is true. That does not last forever.

MD: However, you have to admit that you are curious about how these buildings perform and how they are getting old, used, and transformed.

OD: I am most interested in how the building evolves, if it is maintained in good shape or not. I am curious about how it is now and what kind of feeling I will have inside.

MD: Is the exhibition installation also an exhibited project to be physically experienced?

OD: I hope so, especially this one. My tables are physical. People, the visitors can discover them, say what they want, what they think about, whatever. These tables speak about something else, life.

MD: Yes, I had the feeling that the exhibition is very interactive.

OD: Yes, because people can pick up the posters, relax looking at the projections.

MD: Yes, you can take the memory with you.

OD: Exactly.

MD: What is, to your mind, the crucial point to come to Ostrava for the exhibition? What is the message?

OD: To experience a kind of architecture that is not usual and to experience how it could be perceived, to experience something that you feel with your senses, to enjoy it and to have pleasure, not to ask yourself too many questions, only enjoying. To come and watch the architecture. This may be for the new generation. The young generation is very fast. They do not spend too much time analyzing something. Therefore, this is why.

MD: Thank you very much for your time and effort. I will send you the written version of the interview for your authorization. I would like to also thank the Cabinet of Architecture for organizing both the event and the interview.

The interview was authorized by both Odile Decq and Marie Davidová.

Marie Davidová & Odile Decq

The Cabinet of Architecture had the pleasure of hosting Europe's leading architect’s visit and guest lecture on the occasion of her exhibition at the Gallery of Fine Arts in Ostrava that they organized within their annual, this year’s Tenth International Festival of Architecture, Design, and Art: the Archikulura 2018. Please consider this interview as both your life motivation and as a motivation for your visit to her exhibition HORIZONS, which lasts until June 3, 2018. Marie Davidová, who brings you the following unique interview, was there for the opening and the lecture, representing the Archiweb magazine. The steel queen meets the wooden queen and they discuss horizons!

MD: First, I need to warn you that I am neither a professional journalist nor a theoretician. I perform research by design and therefore I generate theory through experimental practice and also work with education. Therefore, I will be rather asking questions and will wonder based on my personal experience raised and/or motivated by your work and experience.

Did you experience any gender discrimination when starting your career and how do you experience it now?

OD: When I started my career, I was coming to many meetings with a lot of men and I was always asked: Oh, can you take notes? I said no, I am the architect. Can someone of the men take notes? I always had to assert the condition that I am the architect, not a secretary. Often they asked why you are not working in an architect’s office, meaning a man. I said because I am the architect. I received many comments like that until ten years ago or so. Now it is less, even if we still have some sometimes.

When I was starting, I had a feeling of having to prove twice that I am able to do the work in order to get a commission. And I discovered that I have to be much more experienced (than male architects) in terms of what I want to achieve. There was a big distrust in female architects. If you look at the projects that women are achieving today, they are not very big projects but they achieved a lot of them. There is still not equity in architecture.

MD: Personally, do you think there is progress through building your name and/or any progress through society development over that time?

OD: I think this is both. Now people know who I am and they are used to seeing my name. At the same time, society has changed in many countries a little bit, not a lot. There is still discrimination in terms of selection for competitions, in terms of the possibility to reach certain projects. In addition, I have often seen that the problem does not come from us. Because we know we are women, we know that we are architects, we know we are efficient and capable and we have the capacity to do it, and we are able to discuss with men as equals. However, men do not always want to give us this possibility. The initial problem does not come from us but from men.

MD: Is the situation better or worse at the academy or in practice?

OD: In the academy, there are more and more female deans at many places now. So, I think in the end it will change. In terms of teaching, there is no equality. There are not enough women. However, it is changing step by step. Because there are many countries discussing this problem. In practice, there is some progress still to be made.

MD: You founded your own architectural school, the Confluence Institute for Innovation and Creative Strategies in Architecture, in 2014 after being head of École Spéciale d’Architecture in Paris for five years due to disagreements at the place. Today science claims that the academy is one of the most psychopathic environments of all. Was that the reason for it? Alternatively, can you relate to it at all?

OD: Maybe because of competition among people. The problem was that I changed a lot at the school and in the end, the previous teachers said that it was enough. They had a feeling I would push them away. Therefore, because they wanted to protect themselves, they started to be very hard with me. And in the end, they succeeded in infiltrating the council making it difficult for me to continue. This is why I left the school.

MD: So, in a way, you have reached the glass ceiling.

OD: Yes, in a way. I was changing the idea of what an architectural school is. At the beginning, they were shocked but thought, why not. Then they said this is not what they wanted. This was the reason I launched my own school of architecture.

MD: What is personally the most important relation for you between the academy and practice? Is it an enriching feedback loop?

OD: First, I think most of the teachers have to be practitioners. At many universities, the academy is not allowed to practice. I find it very bizarre. Though some practitioners cannot teach and some teachers are not good practitioners, we have to have mixed possibilities. We need to offer diverse perspectives and points of view to students. They can join academia, they can join practice, become entrepreneurs… They can become who they want. This is why we have to employ a mixture in the school. Often, when I was teaching, what I felt in the morning was energetic in the evening. Going to the school was giving me energy, nourishing my mind, and I was trying to nourish the minds of my students. The largest happiness I experienced was when one of my students succeeded in doing something he believed he could not do. Enjoying his gaze at that moment was absolutely the most important for me. When you are a teacher in architecture, I sometimes think that we are not teaching the students something, we only need to help them go forward, to understand what they learn, and how to build themselves. The best satisfaction comes when you discover that your student has discovered who they are, what they want to do, and that they achieve that. I do not want them to repeat what I am doing. I am sure they will not be the same architects as I am. I am not interested in giving them the option to do what I am doing. They have to build their own way. This is important for me.

MD: Let us get to the discussion on confluence. You have stated that architects are special in problem-solving. Do you mean the profession that is trained to handle transdisciplinarity? Moreover, is it really the case of today’s practice? Architecture has been, to a certain degree, an interdisciplinary profession for a long time. However, this is a very different situation than transdisciplinary design process.

OD: I strongly believe that the world is different today than it was before. It is especially different because of the digital world, the possibility of the new tools that we have. Because of that, we need to reinvent and rethink how we educate and practice in the future. I do not know how my students will practice in the future. They have to invent their own ways of doing it. The most important aspect of interdisciplinary for me is the fact that we can nourish the field of architecture with all the other disciplines. When we are facing a problem in architecture, we have to convene all the other disciplines such as sociology, philosophy, art, economy, geography, and so on. You have to be able to synthesize that. Therefore, you have to be able to understand how these disciplines nourish your own ideas and your own possibilities to act. Thanks to that, we are very particular. Because this education gives you strategic tools you are not even realizing. This is why I believe that architects, especially, can help the world more than when they only design buildings. By helping the world, I mean acting, helping communities, helping cities, helping countries, helping companies. Because the way of thinking in architecture is peculiar due to complex situations leading to synthesis and proposals across different scales. The way we proceed is specific and unique. We need to give the students the consciousness of that specificity and the ability to do what they want.

MD: You talk about the redefinition of the architectural profession. Beth Sanders claims that this and other professions have transformed into other, more actual, professions. My wonder is, with the transdisciplinary perspective, whether we should not redefine the professions into fields of interest and totally forget such kind of differentiation.

OD: I do not know. I think if you look at schools of architecture, transdisciplinarity comes only with environment, building construction, and sociology sometimes. However, not every school is thinking about sociology, about art, about philosophy, about the way of thinking the world is enacted. This is why I always say that I am more interested in architecture than in architects. Architect is just a profession. I do not care how to define this profession because for me, architecture is what is important.

MD: You have stated that “The form of a building is really the end of a process.” – Isn’t it when the process starts?

OD: No, I also think that for me it is when the process starts. The form is an important thing. That is what I meant when I said that.

MD: OK, then I misunderstood this statement. I found the confusion between this statement and what one of your students stated that she is actually designing for experience. Building experiences means that when the experience is performed the process starts – not ends to me.

OD: She was doing research on surface, exactly as you do, a 3D printing textile. She managed to find a way to understand how she can build with it. Through that process of experimenting with this little object that was printed, she discovered what she could do. This is learning by doing.

She was like that. However, my students are not myself. For me, the form often comes at the end. Because I am not interested in designing the form and filling it. I prefer to work in a very experimental way and wonder what kind of experiences you can have.

MD: OK, I initially fully misunderstood this sentence. Because I was thinking that you mean that you build the house and then, when the real performance takes place for you the process ends.

OD: No, no.

MD: I love this discussion. The last three questions thematically lead to the topic of your exhibition: The ‘Horizons that cannot be reached.’ This topic is supposed to exhibit the experience – the endless process of becoming the building – its performance. Can you talk more about your personal experience of the exhibited projects?

OD: These nine projects? What do you mean by my personal experience?

MD: You design the house and then you build it. For me, I tend to visit these buildings or any other built stuff. I tend to observe what is happening there.

OD: For me, I do not feel like that. For me, my buildings have their own personal life after me. I cannot control a hundred percent of their evolution. I say that but at the same time, it sounds strange when my first big project, which was a bank, was planned to be destroyed three years ago, I reacted. It did not come from me but from my surroundings. They convinced me that I couldn’t let them tear it down. I had to fight. I fought and it has been saved. Now it will be renovated for another use. It was a bank and now it will be a school for building constructors. I like this idea. So, at the same time I control what the other architect is doing and he is not allowed to modify my façades. However, in the interior, they can do whatever they want because it was an open space building. I have to admit that every time I pass this region, I come to look at this building. Nevertheless, it is not like this with all my buildings. To the restaurant I built, I was coming for lunch or dinner when it was built but not so much now anymore. I do not have time for that. There is a certain time to let the project go, and for that time, I keep going there. Yes, that is true. That does not last forever.

MD: However, you have to admit that you are curious about how these buildings perform and how they are getting old, used, and transformed.

OD: I am most interested in how the building evolves, if it is maintained in good shape or not. I am curious about how it is now and what kind of feeling I will have inside.

MD: Is the exhibition installation also an exhibited project to be physically experienced?

OD: I hope so, especially this one. My tables are physical. People, the visitors can discover them, say what they want, what they think about, whatever. These tables speak about something else, life.

MD: Yes, I had the feeling that the exhibition is very interactive.

OD: Yes, because people can pick up the posters, relax looking at the projections.

MD: Yes, you can take the memory with you.

OD: Exactly.

MD: What is, to your mind, the crucial point to come to Ostrava for the exhibition? What is the message?

OD: To experience a kind of architecture that is not usual and to experience how it could be perceived, to experience something that you feel with your senses, to enjoy it and to have pleasure, not to ask yourself too many questions, only enjoying. To come and watch the architecture. This may be for the new generation. The young generation is very fast. They do not spend too much time analyzing something. Therefore, this is why.

MD: Thank you very much for your time and effort. I will send you the written version of the interview for your authorization. I would like to also thank the Cabinet of Architecture for organizing both the event and the interview.

The interview was authorized by both Odile Decq and Marie Davidová.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment