Hendrik P. Berlage: Frank Lloyd Wright*

Source

Styl IV (IX, 1922-23), s.10-15.

Styl IV (IX, 1922-23), s.10-15.

Publisher

Petr Šmídek

15.07.2013 13:25

Petr Šmídek

15.07.2013 13:25

Hendrik Petrus Berlage

Frank Lloyd Wright

* We present this article as evidence that an artistic movement can be perceived differently than how the creator himself understands it.

The period of rapidly changing artistic directions is simultaneously a time of uncertainty in architecture. Hence, the strength of the individual who creates a "school" as soon as he brings new forms, which means that behind a strong personality follow not only "superficial" followers, admirers attached to outward appearances, but also those who are granted the ability to penetrate to the core of new expression through the force of their talent.

It is a fascination with the "new gesture," which irresistibly attracts, simultaneously encouraging change and spreading with incomprehensible speed. Its effect is akin to that of a stone thrown into a pond. If it were merely a matter of change in general perspective, there could be no talk of a "new gesture." It is not about the disappearance of individual artistic forms, but about a systematic transformation of principles. In short, the moment arrives when personal peculiarities yield to collective generalization.

When I once described my impressions from my journey through America, especially regarding the impressions of the work of Frank Lloyd Wright — this occurred during a lecture — I dared to express the assumption that perhaps one day there will come a time of a "peaceful invasion from America," as a variation of what had preceded from Europe. I wanted to convey that the art of this great builder cannot go unnoticed in Europe, especially since it concerns a typical phenomenon in American architectural art. This is also because it concerns Wright, who follows his master, Sullivan, completely freed from European influences. In the publication of his work, Wright accompanied it with a significant study on the necessity of having a distinctive American style. Wright reflects upon the overview of great artistic periods, appreciating the various styles that culminated in the resistance to the Renaissance.

Remembering this, I find myself in a quandary when I consider how to express the cultural significance of the artist for today's time. It is impossible on this occasion to avoid the fundamental question of whether his work is of a general nature, or whether it represents extraordinary values. I believe that in Wright's case it is the latter; we must value him as a genius artist whose influence is truly guaranteed by the "captivating" gesture. It is the property of genius to express the general in the particular, and the general referred to here signifies the construction of modern "skyscrapers." For although Wright created an artistic center in America, a center of great significance, his work cannot be classified as a purely American type. Otherwise, it would bear the mark of machine work, and every building executed by Wright would inevitably bear the traces of mechanical rationalism, and not a single component could escape it. And this "a priori," under which the artist need not be precisely mechanized, presupposes at the very least that the artist must be safeguarded from romantic sensitivity.

It is difficult for me to judge Wright otherwise than as a romantic, and I cannot see him as an "architect-industrialist," as many would like to see him and as he himself would like to consider himself. Evidence of this can be found in Wright's monograph "In the Cause of Architecture," where he writes:

"From a construction, I demand the same as from a person, namely, that it be honest and internally valuable; and this main property I wish to see united in a whole that is as internally harmonious as possible. But the internal sanctity of this loving bond surpasses everything. Our culture has a tool that has no second. We then have a significant role to prepare for the machine the work it is capable of accomplishing.

To adapt work to possibilities is the essence of the modern industrial ideal that we must create if architecture is to maintain its leading position among the arts and not lose it.”

And then Wright argues that in America there will indeed once stand the cradle of true modern art, which the great individualists of the English movement scorned.

Furthermore, he states: "The extremes are the best friends of artists. We will never rid the world of machines; they will remain as they are, namely, pioneers of democracy, the final goal of our hopes and wishes. For the architect of our time, there is no more significant task than to adapt to this modern tool as much as possible. Yet what does he instead? He abuses machines to create forms that originated under different skies and in other times, to create shapes that act in a paralyzing manner because we distance ourselves from them. And this is done using a machine, whose purpose is precisely to destroy these shapes.”

Wright wrote these words in 1908, and since then we still have not achieved complete victory over the old forms, nor have we achieved it in America. In America, a new style of art must still emerge, which must arise from a machine-based foundation. And such a style, which is entirely different from mere material processing and crafting components — must arise from different foundations.

Does Wright's work correspond to the ideal that Wright himself formulated so sharply? I think I do not harm the greatness of this American when I say no. I do not have the impression, even upon immediate reflection, that it concerns so-called "universal" art; I still only see "personal" tastes and whims, where machine influences only "seemingly" create the foundation.

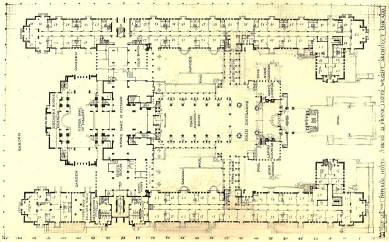

And how does this personal character manifest itself, especially in the country house, which thus far belongs to the most significant field of Wright's activities?

It manifests itself in the consistent horizontalism, with a facade featuring a series of small windows, which gives a lively touch through a slightly protruding and emerging roof.

This horizontalism itself is not particularly extraordinary for Wright. It seems to be, generally speaking, something modern, which we could explain as a reaction to the verticalism that up until now has prevailed and stems from the new gothic style. It is very strongly manifested in the youngest American architecture, especially in the division of window openings. However, the advancing roof, which powerfully affects through the shadows it casts, and then mainly its protective task, those are Wright's characteristics, that is, "the captivating" gesture, the piquant seasoning of the "three-dimensional," as one of Wright's students called his work. In this, Wright indeed remains a captive of a motif that, when used countless times, operates disruptively, having been used asymmetrically. This happens precisely because plans for residential buildings with such beautiful perfection, where the basis of symmetry is usually not at hand, are exhibited to the most perfect effects of spaces and their mutual delicate relationship to the "countryside."

In the use of spaces, Wright demonstrates his strength. Furthermore, being an admirer of living nature, he uses live flowers for decoration. He constructs elongated brick troughs under windows for this decoration and rounded plinths for columns at the entrance to terraces. Externally, his stylistic strength is consistently manifested in long straight lines, especially in heavy machine constructions, and primarily in the forefront. For Wright does not acknowledge curves of any kind, although he uses a semicircular arch here and there at the entrance with great effect; for the ceiling, he uses — which I consider a weakness — colorful vaults, as for example in the "Dana House" in Oak Park. Moreover, the exits are low and substantial, and mighty cornerstones increase the impression. In addition to this, there is heavy furniture constructed purposefully, reminiscent of the early days of modern movements. In the rooms, surprise follows surprise, both through the views from the windows across the colorful foreground into the countryside, as well as through the numerous openings, which, according to American habit, do not have doors leading to neighboring corridors and exits. In this, one cannot help but feel an escalating admiration for the poet of spatial poetry, for he has an extraordinarily fine taste with which he places artworks in the right spots.

Wright has demonstrated his talent primarily in the construction of residential houses. Yet also in the construction of the church (Unity Church) in Chicago, and in the construction of the administration building with factory offices in Buffalo, he found the opportunity to embody his extraordinary art. In the aforementioned church, a rectilinear space, something is enlivened that recalls classical temples, and the aforementioned office building speaks through its heavy mass of the powerful characteristics of strength emanating from today's factories.

In the construction of the church, he used the same motif as he does in country buildings, namely a series of high-placed windows, but the roof is flat this time. He did not use that motif in the administrative building because it does not correspond to the essence of factory offices. For the character of this building, which itself gives a guideline, is in perfect accordance with Wright's "fundamental program." The character of the commercial spaces is manifested here in the massive interior rooms used as workspaces, where we will surely praise with delight that the highest gallery, intended for rest, is decorated with flowers and shrubs.

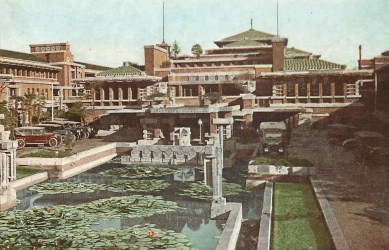

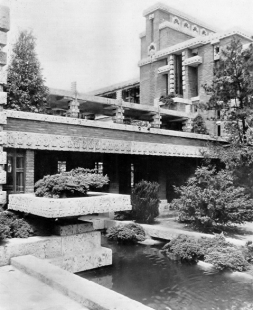

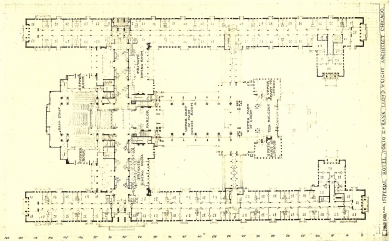

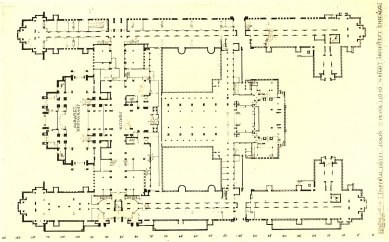

It is appropriate to hope that the scope of Wright's influence will continue to expand. His latest work, a hotel in Tokyo, culminates in the apotheosis of what he embodied in the "Coouley" estate. In the construction of the hotel, he found the opportunity to use unusual dimensions, where he could stretch his imagination to extremes to show how he knows how to handle his own motifs.

As is evident, Wright's talent is extensive. His "ideal projects," which have received that name from architects, were destined never to be executed. Let us point here to the design of a theater in California, envisioned classically and surrounded by an environment that could be called the architecture of Paradise. Let us mention Olivette Hill, a resort realized in the beautiful Californian land, with traces of influences from the East. Perhaps it could be presumed that Wright's stay in Japan can be attributed to the character of architectural execution, as is most clearly manifested in the construction of a garden intended for summer residence and an open-air theater. Here, we encounter columns driven high into the air, and beams and roofs protruding for effect, reminiscent of Japan. Moreover, you will find here figural corbels and finials, terminations that further emphasize the eastern character of the construction. And let us not forget whether the diversity of building styles does not generally originate from the East?

Thus, one can understand the admiration for Wright's work, as well as the confirmation of the words about the prophet's fate, which are greater on this than on the other side of the ocean. Especially the Netherlands, where a distinctive national architectural style is just emerging, has not been spared this "foreign contagion." But can we blame predecessors of such a nature? Has it not always been the case throughout all ages that external influences are apparent?

Translated by R. Vonka

It is a fascination with the "new gesture," which irresistibly attracts, simultaneously encouraging change and spreading with incomprehensible speed. Its effect is akin to that of a stone thrown into a pond. If it were merely a matter of change in general perspective, there could be no talk of a "new gesture." It is not about the disappearance of individual artistic forms, but about a systematic transformation of principles. In short, the moment arrives when personal peculiarities yield to collective generalization.

When I once described my impressions from my journey through America, especially regarding the impressions of the work of Frank Lloyd Wright — this occurred during a lecture — I dared to express the assumption that perhaps one day there will come a time of a "peaceful invasion from America," as a variation of what had preceded from Europe. I wanted to convey that the art of this great builder cannot go unnoticed in Europe, especially since it concerns a typical phenomenon in American architectural art. This is also because it concerns Wright, who follows his master, Sullivan, completely freed from European influences. In the publication of his work, Wright accompanied it with a significant study on the necessity of having a distinctive American style. Wright reflects upon the overview of great artistic periods, appreciating the various styles that culminated in the resistance to the Renaissance.

Remembering this, I find myself in a quandary when I consider how to express the cultural significance of the artist for today's time. It is impossible on this occasion to avoid the fundamental question of whether his work is of a general nature, or whether it represents extraordinary values. I believe that in Wright's case it is the latter; we must value him as a genius artist whose influence is truly guaranteed by the "captivating" gesture. It is the property of genius to express the general in the particular, and the general referred to here signifies the construction of modern "skyscrapers." For although Wright created an artistic center in America, a center of great significance, his work cannot be classified as a purely American type. Otherwise, it would bear the mark of machine work, and every building executed by Wright would inevitably bear the traces of mechanical rationalism, and not a single component could escape it. And this "a priori," under which the artist need not be precisely mechanized, presupposes at the very least that the artist must be safeguarded from romantic sensitivity.

It is difficult for me to judge Wright otherwise than as a romantic, and I cannot see him as an "architect-industrialist," as many would like to see him and as he himself would like to consider himself. Evidence of this can be found in Wright's monograph "In the Cause of Architecture," where he writes:

"From a construction, I demand the same as from a person, namely, that it be honest and internally valuable; and this main property I wish to see united in a whole that is as internally harmonious as possible. But the internal sanctity of this loving bond surpasses everything. Our culture has a tool that has no second. We then have a significant role to prepare for the machine the work it is capable of accomplishing.

To adapt work to possibilities is the essence of the modern industrial ideal that we must create if architecture is to maintain its leading position among the arts and not lose it.”

And then Wright argues that in America there will indeed once stand the cradle of true modern art, which the great individualists of the English movement scorned.

Furthermore, he states: "The extremes are the best friends of artists. We will never rid the world of machines; they will remain as they are, namely, pioneers of democracy, the final goal of our hopes and wishes. For the architect of our time, there is no more significant task than to adapt to this modern tool as much as possible. Yet what does he instead? He abuses machines to create forms that originated under different skies and in other times, to create shapes that act in a paralyzing manner because we distance ourselves from them. And this is done using a machine, whose purpose is precisely to destroy these shapes.”

Wright wrote these words in 1908, and since then we still have not achieved complete victory over the old forms, nor have we achieved it in America. In America, a new style of art must still emerge, which must arise from a machine-based foundation. And such a style, which is entirely different from mere material processing and crafting components — must arise from different foundations.

Does Wright's work correspond to the ideal that Wright himself formulated so sharply? I think I do not harm the greatness of this American when I say no. I do not have the impression, even upon immediate reflection, that it concerns so-called "universal" art; I still only see "personal" tastes and whims, where machine influences only "seemingly" create the foundation.

And how does this personal character manifest itself, especially in the country house, which thus far belongs to the most significant field of Wright's activities?

It manifests itself in the consistent horizontalism, with a facade featuring a series of small windows, which gives a lively touch through a slightly protruding and emerging roof.

This horizontalism itself is not particularly extraordinary for Wright. It seems to be, generally speaking, something modern, which we could explain as a reaction to the verticalism that up until now has prevailed and stems from the new gothic style. It is very strongly manifested in the youngest American architecture, especially in the division of window openings. However, the advancing roof, which powerfully affects through the shadows it casts, and then mainly its protective task, those are Wright's characteristics, that is, "the captivating" gesture, the piquant seasoning of the "three-dimensional," as one of Wright's students called his work. In this, Wright indeed remains a captive of a motif that, when used countless times, operates disruptively, having been used asymmetrically. This happens precisely because plans for residential buildings with such beautiful perfection, where the basis of symmetry is usually not at hand, are exhibited to the most perfect effects of spaces and their mutual delicate relationship to the "countryside."

In the use of spaces, Wright demonstrates his strength. Furthermore, being an admirer of living nature, he uses live flowers for decoration. He constructs elongated brick troughs under windows for this decoration and rounded plinths for columns at the entrance to terraces. Externally, his stylistic strength is consistently manifested in long straight lines, especially in heavy machine constructions, and primarily in the forefront. For Wright does not acknowledge curves of any kind, although he uses a semicircular arch here and there at the entrance with great effect; for the ceiling, he uses — which I consider a weakness — colorful vaults, as for example in the "Dana House" in Oak Park. Moreover, the exits are low and substantial, and mighty cornerstones increase the impression. In addition to this, there is heavy furniture constructed purposefully, reminiscent of the early days of modern movements. In the rooms, surprise follows surprise, both through the views from the windows across the colorful foreground into the countryside, as well as through the numerous openings, which, according to American habit, do not have doors leading to neighboring corridors and exits. In this, one cannot help but feel an escalating admiration for the poet of spatial poetry, for he has an extraordinarily fine taste with which he places artworks in the right spots.

Wright has demonstrated his talent primarily in the construction of residential houses. Yet also in the construction of the church (Unity Church) in Chicago, and in the construction of the administration building with factory offices in Buffalo, he found the opportunity to embody his extraordinary art. In the aforementioned church, a rectilinear space, something is enlivened that recalls classical temples, and the aforementioned office building speaks through its heavy mass of the powerful characteristics of strength emanating from today's factories.

In the construction of the church, he used the same motif as he does in country buildings, namely a series of high-placed windows, but the roof is flat this time. He did not use that motif in the administrative building because it does not correspond to the essence of factory offices. For the character of this building, which itself gives a guideline, is in perfect accordance with Wright's "fundamental program." The character of the commercial spaces is manifested here in the massive interior rooms used as workspaces, where we will surely praise with delight that the highest gallery, intended for rest, is decorated with flowers and shrubs.

It is appropriate to hope that the scope of Wright's influence will continue to expand. His latest work, a hotel in Tokyo, culminates in the apotheosis of what he embodied in the "Coouley" estate. In the construction of the hotel, he found the opportunity to use unusual dimensions, where he could stretch his imagination to extremes to show how he knows how to handle his own motifs.

As is evident, Wright's talent is extensive. His "ideal projects," which have received that name from architects, were destined never to be executed. Let us point here to the design of a theater in California, envisioned classically and surrounded by an environment that could be called the architecture of Paradise. Let us mention Olivette Hill, a resort realized in the beautiful Californian land, with traces of influences from the East. Perhaps it could be presumed that Wright's stay in Japan can be attributed to the character of architectural execution, as is most clearly manifested in the construction of a garden intended for summer residence and an open-air theater. Here, we encounter columns driven high into the air, and beams and roofs protruding for effect, reminiscent of Japan. Moreover, you will find here figural corbels and finials, terminations that further emphasize the eastern character of the construction. And let us not forget whether the diversity of building styles does not generally originate from the East?

Thus, one can understand the admiration for Wright's work, as well as the confirmation of the words about the prophet's fate, which are greater on this than on the other side of the ocean. Especially the Netherlands, where a distinctive national architectural style is just emerging, has not been spared this "foreign contagion." But can we blame predecessors of such a nature? Has it not always been the case throughout all ages that external influences are apparent?

Translated by R. Vonka

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment