|

| David Chmelař (*1978, Náchod) studium 1997-2003 FA ČVUT Praha2001-2002 FS ČVUT Praha 1992-1997 VOŠS - SPŠS Náchod praxe od 1998 soukromá praxe2001 Jiran Kohout architekti 1993-1999 Atelier Tsunami |

|

| David Chmelař (*1978, Náchod) studium 1997-2003 FA ČVUT Praha2001-2002 FS ČVUT Praha 1992-1997 VOŠS - SPŠS Náchod praxe od 1998 soukromá praxe2001 Jiran Kohout architekti 1993-1999 Atelier Tsunami |

|

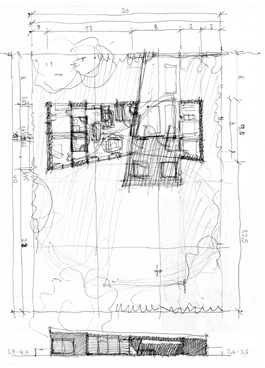

| Family house in Dřevíč, 2003 |

|

| Ice Stadium in Hronov, 2002 - 2004 |

|

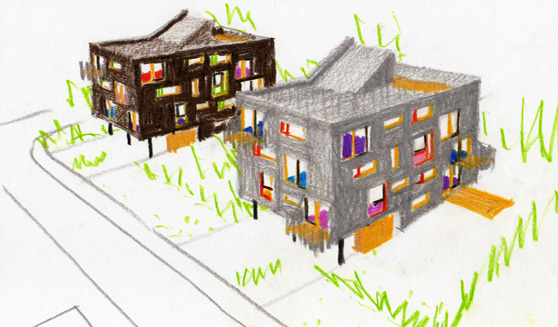

| Two houses with starter apartments in Polici nad Metují, 2002 - 2005, sketch 2002 |

|

| Renovation of Kostelní Square in Broumov, 2005 - 2007 |

|

| Revitalization of the center of Hronov, 2008 - 2009 |

|

| One of the variants of your summer house in Hronov, 2007 |

|

| One of the variants of your summer house in Hronov, 2008 |

|

| Family house in Česká Skalice, visualization, 2008 |

|

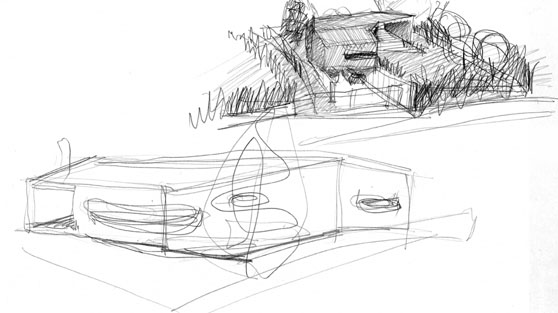

| Family house in Česká Skalice, first sketch, 2008 |