The Berlin Wall began to be built 50 years ago

|

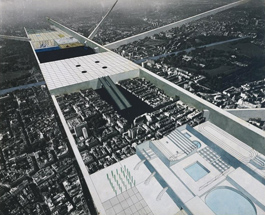

| Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture, Exhausted Fugitives Led to Reception (Rem Koolhaas, Elia Zenghelis, Madelon Vriesendorp, Zoe Zenghelis; 1972) |

The place that best illustrates the absurdity and perversion of the long-term division of Berlin and the entire country is located on the western edge of the German metropolis. The village of Klein-Glienicke lies in the territory of former West Berlin, but falls under nearby Potsdam and was therefore already part of communist East Germany. As its outpost surrounded on all sides by the "class enemy," it became one of the most strictly guarded sections of the Berlin Wall.

The village with 500 inhabitants, not far from the famous "Bridge of Spies," where Americans and Soviets exchanged detained agents during the Cold War, was encircled 50 years ago by a barbed wire fence, later replaced by two rows of up to four-meter high concrete panels, completely cutting it off from the outside world. The only connection was a small bridge over the river canal, separating Klein-Glienicke from the film-famous Potsdam district of Babelsberg. Crossing to the other side was possible only with a pass and after passing a police check.

"I still remember when everything was free and nice, when one could freely walk through the forests, sail on the river," recalls today sixty-nine-year-old Heinrich, who was born in Klein-Glienicke and spent more than half of her life there. On fateful August 13, 1961, when the borders between East and West Berlin were closed and the construction of barriers began, she was on vacation with her boyfriend at the Baltic Sea. They could not return through Berlin, and they only allowed her into her hometown. Her boyfriend with a different permanent residence was not permitted into the emerging exclave.

"I couldn't believe it was possible to cut off a place like that, and there was only a fence at that time. It got worse in 1965 when the first and second wall were built," recounts the then student and later physical education teacher, for whom life among the gray panels became an everyday reality for the next 15 years.

|

| Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture, Exhausted Fugitives Led to Reception (Rem Koolhaas, Elia Zenghelis, Madelon Vriesendorp, Zoe Zenghelis; 1972) |

By 1980, life in this concrete fortress had become unbearable for her, and she requested the opportunity to relocate with her family. "It just couldn’t go on any longer," she admits. She says she thought briefly about escaping to West Berlin right after the wall started being constructed. However, out of fear for the fate of her parents and siblings in Klein-Glienicke, she dismissed the idea and stayed. Like most residents of East Germany, she did not visit until after the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989.

"It was the best birthday present," she laughs even today at the coincidence, as she celebrates her birthday on exactly the day the border to the western part of the metropolis reopened.

From the approximately 155-kilometer-long concrete barrier, only remnants remain to remind of the post-war division of the city and the fates of more than a hundred East Germans who lost their lives attempting to escape over the wall, as well as thousands of others who were deprived of relatives and friends on the other side for 28 years. While for the survivors like Gitta Heinrich, the memory of it remains painful, for others it has become a generous source of income and a magnet for foreign visitors.

At tourist-attractive sites associated with the wall in the city center, such as the Brandenburg Gate, Potsdamer Platz, or the former sector crossing Checkpoint Charlie, entrepreneurs in period military uniforms stand every day and for a few euros stamp excited foreigners’ passports and take photos with them. Anyone wishing to get acquainted with the route of the wall and view its remnants can choose from an endless offer of walking tours, cycling and bus excursions, or opt for the popular "Trabant safari." Everything, of course, is with a guide. And for those who are not satisfied with just bringing home experiences and photos, almost every corner in the center offers supposedly guaranteed authentic pieces of the Berlin Wall for sale.

This commercialization of the city’s recent history has many critics who warn that it is slowly becoming a "Disneyland of the Cold War," calling for official restrictions on these activities out of respect for the victims of the wall. "Costumed border guards in central Berlin are a disregard for the victims," asserts Hubertus Gnabe, head of the museum of the former East German secret police, Stasi.

For Berlin itself, however, it is a significant source of income that the debt-ridden metropolis would part with only with a heavy heart. According to estimates, approximately 5.5 million people currently come annually for the monuments and attractions related to the existence of the two German states, which represents about a quarter of all visitors to Berlin.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment