Palace of the General Pension Institute

<div>House of Trade Unions, Building of the Revolutionary Trade Movement, House of Joy</div>

This building and its design is so far my most significant realized architectural work, and the same applies equally to Karel Honzík. I have therefore decided to include it in this book, at least in a brief summary, although it has been published so many times in many countries, in books and magazines.

The so-called competition, which the former VPÚ announced in June 1929 to obtain a design for its new building in Žižkov, was not a true competition. VPÚ purchased designs from nine authors for a fee, without any further obligations other than respecting copyright. There was also no competition jury. The institute's technicians (which owned several different buildings) conducted a precise check of all the data contained in the designs, calculations of areas, volumes of the enclosed space, etc. In addition, the institute requested several opinions on the designs from various experts. The result of the data verification was the finding of an average volume of over 200,000 m³ for eight designs and 150,000 m³ for ours. According to the final formation of the construction cost, this represented a difference of more than 20 million Kčs, which could already be roughly estimated in advance. And this was ultimately decisive for the acceptance of our design for implementation. Additionally, there was also an operational distinction between our design and the others. A labyrinth in the majority of designs, clear orientation, full illumination of all components of the building, etc., in our design. It was written about the adherence or non-adherence to the given conditions, but nothing like that was at stake. The stopping directive of the valid regulatory plan was communicated to all involved, and whether they complied or not was a matter of their designs — the highest possible risk.

The architecture of our design was disliked by the vast majority of the institute's leading officials, and in some cases, it sparked fierce resistance. To their credit, it must be stated that given the previously mentioned facts, which were significant from an economic responsibility perspective and proven by experts, they explicitly renounced the right to impose their opinion on the matter of architecture, and they adhered to this.

It would not be suitable to delve here into a description of the two-year "war of nerves" until certainty about the implementation of the design was achieved, which was only granted by the commissioning of work on the detailed project; our hope and encouragement were already the assignment of the so-called definitive draft during this time. This second design already contained adjustments in accordance with the requirements of the then State Regulatory Commission, particularly the rearrangement of the upper and lower wings of the central cross building in a way that was essentially realized later.

Although the architecture of the building was largely left to our responsibility, there were still many battles over some of its essential features. In the overall score, there are two significant defeats — the construction system with cantilevered facades of the building and the steel load-bearing frame. The cantilevered facades were rejected by the building commission of the institute even before the project destined for execution began, despite a large model of the office composition and persuasion of several people. The cantilevers remained only in the street facades of the lower wings. As for the steel frame, the first two stages of the design contemplated it as a logical consequence of the then-current standards for reinforced concrete structures, according to which the dimensions of construction elements became unacceptably massive due to the required height of the building. In the design designated for execution, the builder temporarily decided for reinforced concrete, but already dimensioned according to the new standards from 1932, which provided considerably more favorable dimensions than had been possible before, yet dimensions around one meter, for instance, for the basement pillars remained.

With the assistance of workers requested from the steelworks, we then concurrently worked on a variant design 1:100 in steel. This led to the well-known unnecessary disputes "steel or reinforced concrete?", which recurred with each larger construction. The assessing expert from the city, a reinforced concrete specialist, for instance, imposed the condition that the fireproof cover of the steel pillars in the rooms, for which a troweled wire mesh about 5 cm thick sufficed everywhere, must be reinforced almost similarly to Hennebique's load-bearing pillar. Thus, the costs of the steel structure increased pleasingly, as it seemed desired. It decided that when finalizing the designs, the reinforced concrete variant allowed for the immediate commencement of construction, whereas the steel variant required, according to the commission's assessment with a predominance of reinforced concrete experts, some more time to address deficiencies, e.g., in the foundation, which unfortunately the steel experts had truly overlooked. Hence, the steel structure was more expensive. The statement from the steelworks that they would discount the entire cost difference of more than two million did not help either. Here, one can realize how much progress theory and practice in the use of reinforced concrete have made from then until today, when it is already used in Europe for buildings over thirty stories tall and in North America for sixty-story buildings.

Against the aforementioned "loss points," which no longer seem so significant to us as they did then, stand two notable victories, which, as I believe, have not lost their importance: air conditioning and the ceramic cladding of the building.

We defended air conditioning from the very first comprehensive exploration of the office building area. Even for the second stage of the draft (the so-called definitive), we managed to obtain a preliminary project for a Carrier system air conditioning. This system, in connection with our then Škoda Works, which undertook almost the entire project execution, except for quantitatively minor patented components, e.g., automatic regulators, stood in later competition against combinations of radiator central heating with supplementary ventilation, which usually served only for the building manager, in an effort to save, never to turn it on. The radiator competition was so confident of victory over the unknown and supposedly very costly innovation that it raised the pricing of its metric quintals of cast-iron radiators to such an extent that it helped the air conditioning to win.

The ceramic cladding was for a long time a painful issue in the development of the design. Concepts like břízolit or plaster gradually became a nightmare for me, with visions of a charred mass of the building under the black-gray desolation of Žižkov. The rough construction was nearing completion, and the ceramic cladding of the facades had already been definitively rejected twice. By the winter of 1932, large samples of several claddings and a břízolit plaster sample, half covered with asphalt paper, were prepared. Early that spring, we tried once more to bring the cladding up for discussion. A meeting of the building commission took place at the construction site in an old ground-floor house, where we also had our offices. Reluctantly, it was conceded to talk about the matter at all; the old arguments resurfaced, with concerns about tiles falling on people's heads, about the supposed resemblance of the building to heating stoves, and other forms were found — supposedly it would resemble a toilet on Wenceslas Square, pulled from the underground, like a glove turned inside out, etc. Because it was snowing a little, no one wanted to go outside to view the samples after the winter, until finally, in our outraged protest against deciding at the green table when just a few steps away there were concrete samples from many works costing tens of thousands made, one of the key members of the institutional commission stood up and, with the words "the architect is right," rolled up his collar and prepared to leave — and the others followed him.

The samples were silently examined, and the commission stood awkwardly before them. We provided a brief report and then removed the paper from the covered part of the plaster sample. Everyone was surprised by the contrast, which was absolutely convincing and confirmed our arguments from all previous discussions — the light original color next to the almost black — in just a few weeks. Someone tried to brush it off with a joke, suggesting that we could have saved the money we had to pay the night watchman for watering the sample with soot-laden water. However, it was enough to point to the neighboring station with rolling clouds of black smoke, and everyone felt that it was probably just pure truth when we told the relevant person something about throwing money away on something that our heating plant provided us for free.

Upon returning to the warmth of the office, the commission was as if transformed — someone said to at least dismiss those "tiles," acknowledging the necessity of a more solid material for the façade of the building, and what the designers would say about cladding with stone slabs? Of course, we were very in favor of this, but for the sake of the lay members of the commission, we repeated that this involves an area of about 16,000 m² and provided some prices for 1 m² of various cladding materials, including labor: the cheapest, not very suitable cladding from new bricks around 90 crowns of the then currency, dursilit Rakodur about 180 to 200 crowns, granite of inferior quality around 500 crowns, good quality granite slabs approximately 1000 crowns. The price of about 30 crowns of the then currency for 1 m² of břízolit was known to everyone, but the maintenance costs and other expenses were not considered, as soon after a number of years, the plaster began to fall off meter by meter. The plasters that seemed nice to someone somewhere were stone worked and according to the materials crushed were certainly much more expensive, around 100, but rather 150 crowns for 1 m² (e.g., at the former Exhibition Palace), others even over 300 crowns and the risk of peeling threatens more or less all the same (see again the Exhibitions). The discussion lasted only a moment longer before Rakodur was voted for (which we had not even dared to dream of as a realistic option), and this was with all votes except the chairman, who remained loyal to his view "against stoves." That was his opinion, and I do not value him any less for it; without his attitude towards the construction of the new building, our design would hardly have been realized.

The narrative about these rather detailed, albeit important matters has gone somewhat far, but perhaps it is better than presenting many details about construction, which can be learned from earlier publications in the library if anyone needs them. Nevertheless, at least general information about the whole building must be provided, and it is necessary to touch upon the principles from which the design was based.

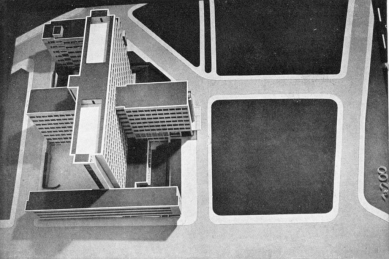

The basic principle of the official building was the central construction of the land with a cross-shaped floor plan, connecting on the floor the optimal number of four three-wing office wings to one operational center, and such partial components of these floors then mutually connect at a proportionate elevation of the building with a vertical spine of quick elevators. This is a highly economical principle, with many desirable properties otherwise unattainable, such as orientation clarity, illumination, short horizontal connections, central vertical installations, etc.; moreover, it realizes the apparent paradox of immediate connectivity while simultaneously complete separation of the four working groups at the central hall, which can have significant meaning for certain types of buildings (higher education and research institutions, hospitals, etc.) for otherwise unmanageable solutions. The described basic principle was here thought out in a large format and relatively pure architectural form and realized practically for the first time. This fact was not long understood in our country. Even less could there be understanding for such a simple thing, as that every achieved stage in something is only a precursor to the next, as this marks the developmental path of progress.

After almost thirty years since then, nothing can change the fact that there was a lack of timely opportunities to address those various tasks to which this realization logically and naturally opened a direct path. Foreign interest, significantly boosted by broad publicity and certainly also the related problems, for which solutions were sought, led to many realizations around the world, sometimes even striking replicas or forms. Domestic interest in the matter, whatever it was, largely slipped into a dead end of thoughts about a ruined Prague panorama. A smaller portion of interest, rather professional, was devoted to the VPÚ building usually in connection with the building of the Transport Enterprises in Holešovice, completed around the same time. Although it is a very significant modern building, it nonetheless lacks the basis for comparison, which could only consider the Žižkov struggle for the realization of the principles indicated above. Perhaps the merging of facts was facilitated by the fact that the building commission of the then Electric Enterprises, which based itself in many ways on similar decisions in the then VPÚ, also decided for the secondary use of the air conditioning patent Carrier and, in particular, for the ceramic cladding of the building façade with Rakodur slabs, which gave both buildings an apparent external similarity.

As for the temporary "ruin" of the Prague panorama, it was already clear to us upon the conception of the VPÚ design that the building was only the beginning of future wider construction and its component. After the completion of the building, it could be clear to anyone who considered the matter more thoroughly that the building could not be conceived as part of the already dying, charred Žižkov, but only as a component of a broader sanitary reconstruction of the future.

This situation has fundamentally not changed to this day, although a time lag has occurred, as brought about by the historical events of the last quarter-century. More detailed information about the development of the surrounding buildings of the current ROH building is provided in the book when working on this issue of Prague reconstruction, especially in a study from 1957, when Karel Honzík and I were given the opportunity to participate in a limited competition by the Ministry of Transport for partial completion of the surroundings. There we could, albeit at the cost of not adhering to the competition conditions, at least roughly fix our opinion on the necessity of solving an area much broader. Prague was fortunate that the result of this competition did not result in realization. Two years later, in 1959, I had another opportunity in our design institute to study this topic again (the study of the development of the surrounding area of the ROH building is published later).

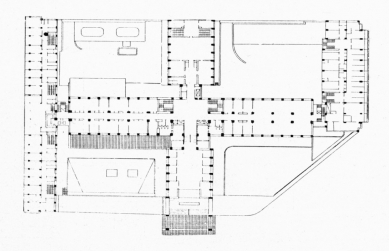

At the end, I will add at least some data about the ROH building (former VPÚ). The construction program had further spatial requirements beyond the official building itself. Our goal was to achieve a clear arrangement of all program components. The central cross part contains about 650 office cells with axes (large module) of 3.40 m and a depth from the parapet boxes to the boxes along the central corridor of 5.80 m. These were grouped as needed into larger halls or, conversely, isolated, e.g., in the mathematics department. In addition to offices, there are smaller and larger meeting rooms in the center, a lecture hall for about 400 people, a boiler room, machine rooms, transformer stations, etc. The southern low wing contains official apartments, while we supplemented the northern wing facing Kalinin Street with rented apartments and offices on the floors; there was also a café, and on the ground floor, entirely shops, to ensure that the lively street with the construction of the official building did not become lifeless. The low construction in the open yards to the east contains garages and auxiliary facilities.

Regarding the ceramic cladding with Rakodur slabs, I note that the normal format 40 x 20 x 1.8 cm was adapted to the cladding format based on the 3.40 axis module with 8 mm joints to the format of blocks 37.7 x 19.2 x 1.8 cm. In addition, the apartments would have special blocks, e.g., corner and especially drip edges running below the window strips. The execution of the cladding was done with scientific precision and constant control. (This is detailed in the article by engineer Hineis in the publication that the journal Stavitel issued about the construction in 1935 to 1936. There are also detailed data on all components of the building's mechanical and technical equipment, especially regarding the air conditioning system.) A few remarks should be made regarding the air conditioning systems.

Some complaints have been raised over time about their proper functioning. Those that are real and do not originate solely from a certain bias usually stem from the fact that the air conditioning had to meet a variety of different requirements, sometimes even changed later (the case of the former Electric Enterprises), and here it is hard to achieve satisfactory results. A bird that has to chirp seven songs probably will not learn even one properly. Furthermore, it is essential to distinguish well so that the shortcomings of a specific installation are not attributed to the principle of the device itself; this was often done. And to reduce operational costs, especially cooling, it is necessary to utilize the principle of "longevity" — to eliminate, if possible, the consumption of active energy, which is always disproportionately higher than the energy needed to maintain operation. The mentioned publication also describes adjustments to the expansion joints, which received considerable attention, and a number of other data, which cannot be accommodated here, are elaborated on in more detail. Construction began on April 1, 1932, and was worked on until February 28, 1934, a total of 22 months. On March 1, 1934, the institute moved into the new building. With a cubic volume of 149,480 m³ of the enclosed space of all components of the building, the total construction costs, starting from the preparation and drainage of the land with all works, as well as with machinery and internal equipment, totaled approximately 64 million Kčs.

Public Competition for the Development of the Area Surrounding the ROH Building (VPÚ)

Josef Havlíček and Emanuel Hruška, 1940

Although it was clear that no construction could take place during the war, participation in the competition was relatively large, especially given the extent of the requested works — 27 designs. The jury probably understood the overall situation and did not award any prize, but rather aimed to distribute the total available funds as rewards to almost all projects. The method of proposing and evaluating the competition is evident from the diagrams of all designs classified according to rewards in images 85 to 88. Given the local anchoring stemming from the VPÚ building design, I wanted to participate in the competition, but while working on another task, it was too broad of a task. I teamed up with Emanuel Hruška, who was in a similar situation. Karel Honzík was then ill and undergoing long-term treatment.

We published the design the same year in the publication "Towards a New Žižkov," along with considerations about the desired further development of the construction of the given area.

I will quote a few paragraphs from this publication concerning the adaptation of the development to the VPÚ building (ROH), our position on the development of the long plot C, and the open development in general. "Regarding the question: adaptation to the surroundings. Our development system consciously builds on the development system at the General Pension Institute. We proceed from the assumption that it would not be right to disregard principles that have proven their longevity in practice just because such a thing is situated right next to it. We know well certain shortcomings of the VPÚ building, but we also know that its basic operational principle is correct and has stood the test well. Adaptation is necessary not only for operational reasons but also for formal reasons and is given by the proximity of the VPÚ building. A significant number of competition designs did not realize this axiom, to which the division of the plots by Nová Street into a triangular and trapezoidal part may have contributed.

The disadvantageous triangular shape of block B is still a less serious problem than connecting the narrow plot C to the adjacent part occupied by old apartment buildings.

However, the trapezoidal plot C is only part of the block, not the entire block. The builder must have been aware of the difficulties and difficult-to-solve deficiencies for his new buildings if he is to necessarily and unfavorably influence his costly new constructions by the existing tenement developments, which already have a larger part of their lifespan behind them.

With an extraordinarily extensive construction program, of which even the competition conditions state that it is still insufficient, it is incomprehensible why the Ministry of Finance has not been shown the technical necessity of purchasing the remaining part of the block long before, which, even with demolitions, would hardly be more expensive than the price of the free plots B and C. For every building proposal for the so-called block C must parasitically utilize the free spaces behind the old apartment buildings in the remaining part of the block. This way, however, future construction sites in the remaining area become devalued, as in the places of today's old tenement houses, there is already little left for future modification, if proper ventilation is to remain and if the development of administrative buildings on the so-called block C is to be genuinely open development." In the competition, however, one had to count the plots B and C as established variables.

The so-called open development, according to the majority of the jury and apparently also the competition organizers' views, completely turns the principle of open development upside down. Where "inappropriate" surrounding construction allowed, for instance, 4 to 5 stories only around the perimeter of the plot, and the courtyard had to remain vacant, there they would simply carry out the alleged open development, i.e., almost surround the entire perimeter of the plot, but immediately to heights of 7 to 11 stories, and into the courtyard, which previously had to remain unbuilt, they would "openly" erect as many high transverse wings as could fit while maintaining a ratio of 1:1 between the wings.

It was good that the competition made this vulgar error apparent, and despite all shortcomings, it contributed to recognition of the problems. I also provide a quote from the conclusion of the publication:

"In a certain sense, the road to the new Žižkov is a road to a new Prague. We cannot restrict ourselves to just this one place, for even the mere accidental emergence of such beginnings of reconstruction would be contrary to the goal of the nascent architectural revival. Its purpose and ultimate meaning, as is the purpose of other arts, is to realize the art of living. Those office buildings in Žižkov are only part of the Žižkov quarter, which is only part of Prague, and that again is only a section of the life of the country. From architecture as the art of sealing in rotary old blocks or from architecture within the confines of mere huts in general, the evolution towards urbanism as the art of planning on solid foundations of architectural sovereignty in detail leads to a vibrant and healthy city in greenery, whose rapid transport routes are separated from pedestrian paths leading through parks, where rare monuments are cared for, and old debris is cleared away, giving way to orchards, paths, and new buildings, in which instead of neighborhoods crammed with dens, spacious residential neighborhoods breathe freely.

After two decades, we live in a state that has achieved socialism and proudly acknowledge this fact, especially in comparison with the dark period of occupation. We concluded the then publication with a postscript in which we stated the postulate of planning, planned economy — aware that these are so far words that may affect reality only after victory over German fascism. That fortune came to us five years later. In the fifteen years of further development, in which the planned economy soon became the very foundation of our state economy, much has already been achieved that previously simply seemed incredible, and much is approaching realization, what in the occupation we had to consider a dream of a distant future. Perhaps it is not even necessary to add that it absolutely does not matter that the reality has developed in some ways differently; it is clear that we could not, for example, begin with the reconstruction and completion of Žižkov while it was necessary to build industry, housing, and resolve other far more urgent tasks. However, even the construction of this significant Prague complex is beginning to ripen for inclusion in the prospective economic plan, and it will be necessary to ensure that proposals worthy of our time are studied and prepared for realization in due time.

The so-called competition, which the former VPÚ announced in June 1929 to obtain a design for its new building in Žižkov, was not a true competition. VPÚ purchased designs from nine authors for a fee, without any further obligations other than respecting copyright. There was also no competition jury. The institute's technicians (which owned several different buildings) conducted a precise check of all the data contained in the designs, calculations of areas, volumes of the enclosed space, etc. In addition, the institute requested several opinions on the designs from various experts. The result of the data verification was the finding of an average volume of over 200,000 m³ for eight designs and 150,000 m³ for ours. According to the final formation of the construction cost, this represented a difference of more than 20 million Kčs, which could already be roughly estimated in advance. And this was ultimately decisive for the acceptance of our design for implementation. Additionally, there was also an operational distinction between our design and the others. A labyrinth in the majority of designs, clear orientation, full illumination of all components of the building, etc., in our design. It was written about the adherence or non-adherence to the given conditions, but nothing like that was at stake. The stopping directive of the valid regulatory plan was communicated to all involved, and whether they complied or not was a matter of their designs — the highest possible risk.

The architecture of our design was disliked by the vast majority of the institute's leading officials, and in some cases, it sparked fierce resistance. To their credit, it must be stated that given the previously mentioned facts, which were significant from an economic responsibility perspective and proven by experts, they explicitly renounced the right to impose their opinion on the matter of architecture, and they adhered to this.

It would not be suitable to delve here into a description of the two-year "war of nerves" until certainty about the implementation of the design was achieved, which was only granted by the commissioning of work on the detailed project; our hope and encouragement were already the assignment of the so-called definitive draft during this time. This second design already contained adjustments in accordance with the requirements of the then State Regulatory Commission, particularly the rearrangement of the upper and lower wings of the central cross building in a way that was essentially realized later.

Although the architecture of the building was largely left to our responsibility, there were still many battles over some of its essential features. In the overall score, there are two significant defeats — the construction system with cantilevered facades of the building and the steel load-bearing frame. The cantilevered facades were rejected by the building commission of the institute even before the project destined for execution began, despite a large model of the office composition and persuasion of several people. The cantilevers remained only in the street facades of the lower wings. As for the steel frame, the first two stages of the design contemplated it as a logical consequence of the then-current standards for reinforced concrete structures, according to which the dimensions of construction elements became unacceptably massive due to the required height of the building. In the design designated for execution, the builder temporarily decided for reinforced concrete, but already dimensioned according to the new standards from 1932, which provided considerably more favorable dimensions than had been possible before, yet dimensions around one meter, for instance, for the basement pillars remained.

With the assistance of workers requested from the steelworks, we then concurrently worked on a variant design 1:100 in steel. This led to the well-known unnecessary disputes "steel or reinforced concrete?", which recurred with each larger construction. The assessing expert from the city, a reinforced concrete specialist, for instance, imposed the condition that the fireproof cover of the steel pillars in the rooms, for which a troweled wire mesh about 5 cm thick sufficed everywhere, must be reinforced almost similarly to Hennebique's load-bearing pillar. Thus, the costs of the steel structure increased pleasingly, as it seemed desired. It decided that when finalizing the designs, the reinforced concrete variant allowed for the immediate commencement of construction, whereas the steel variant required, according to the commission's assessment with a predominance of reinforced concrete experts, some more time to address deficiencies, e.g., in the foundation, which unfortunately the steel experts had truly overlooked. Hence, the steel structure was more expensive. The statement from the steelworks that they would discount the entire cost difference of more than two million did not help either. Here, one can realize how much progress theory and practice in the use of reinforced concrete have made from then until today, when it is already used in Europe for buildings over thirty stories tall and in North America for sixty-story buildings.

Against the aforementioned "loss points," which no longer seem so significant to us as they did then, stand two notable victories, which, as I believe, have not lost their importance: air conditioning and the ceramic cladding of the building.

We defended air conditioning from the very first comprehensive exploration of the office building area. Even for the second stage of the draft (the so-called definitive), we managed to obtain a preliminary project for a Carrier system air conditioning. This system, in connection with our then Škoda Works, which undertook almost the entire project execution, except for quantitatively minor patented components, e.g., automatic regulators, stood in later competition against combinations of radiator central heating with supplementary ventilation, which usually served only for the building manager, in an effort to save, never to turn it on. The radiator competition was so confident of victory over the unknown and supposedly very costly innovation that it raised the pricing of its metric quintals of cast-iron radiators to such an extent that it helped the air conditioning to win.

The ceramic cladding was for a long time a painful issue in the development of the design. Concepts like břízolit or plaster gradually became a nightmare for me, with visions of a charred mass of the building under the black-gray desolation of Žižkov. The rough construction was nearing completion, and the ceramic cladding of the facades had already been definitively rejected twice. By the winter of 1932, large samples of several claddings and a břízolit plaster sample, half covered with asphalt paper, were prepared. Early that spring, we tried once more to bring the cladding up for discussion. A meeting of the building commission took place at the construction site in an old ground-floor house, where we also had our offices. Reluctantly, it was conceded to talk about the matter at all; the old arguments resurfaced, with concerns about tiles falling on people's heads, about the supposed resemblance of the building to heating stoves, and other forms were found — supposedly it would resemble a toilet on Wenceslas Square, pulled from the underground, like a glove turned inside out, etc. Because it was snowing a little, no one wanted to go outside to view the samples after the winter, until finally, in our outraged protest against deciding at the green table when just a few steps away there were concrete samples from many works costing tens of thousands made, one of the key members of the institutional commission stood up and, with the words "the architect is right," rolled up his collar and prepared to leave — and the others followed him.

The samples were silently examined, and the commission stood awkwardly before them. We provided a brief report and then removed the paper from the covered part of the plaster sample. Everyone was surprised by the contrast, which was absolutely convincing and confirmed our arguments from all previous discussions — the light original color next to the almost black — in just a few weeks. Someone tried to brush it off with a joke, suggesting that we could have saved the money we had to pay the night watchman for watering the sample with soot-laden water. However, it was enough to point to the neighboring station with rolling clouds of black smoke, and everyone felt that it was probably just pure truth when we told the relevant person something about throwing money away on something that our heating plant provided us for free.

Upon returning to the warmth of the office, the commission was as if transformed — someone said to at least dismiss those "tiles," acknowledging the necessity of a more solid material for the façade of the building, and what the designers would say about cladding with stone slabs? Of course, we were very in favor of this, but for the sake of the lay members of the commission, we repeated that this involves an area of about 16,000 m² and provided some prices for 1 m² of various cladding materials, including labor: the cheapest, not very suitable cladding from new bricks around 90 crowns of the then currency, dursilit Rakodur about 180 to 200 crowns, granite of inferior quality around 500 crowns, good quality granite slabs approximately 1000 crowns. The price of about 30 crowns of the then currency for 1 m² of břízolit was known to everyone, but the maintenance costs and other expenses were not considered, as soon after a number of years, the plaster began to fall off meter by meter. The plasters that seemed nice to someone somewhere were stone worked and according to the materials crushed were certainly much more expensive, around 100, but rather 150 crowns for 1 m² (e.g., at the former Exhibition Palace), others even over 300 crowns and the risk of peeling threatens more or less all the same (see again the Exhibitions). The discussion lasted only a moment longer before Rakodur was voted for (which we had not even dared to dream of as a realistic option), and this was with all votes except the chairman, who remained loyal to his view "against stoves." That was his opinion, and I do not value him any less for it; without his attitude towards the construction of the new building, our design would hardly have been realized.

The narrative about these rather detailed, albeit important matters has gone somewhat far, but perhaps it is better than presenting many details about construction, which can be learned from earlier publications in the library if anyone needs them. Nevertheless, at least general information about the whole building must be provided, and it is necessary to touch upon the principles from which the design was based.

The basic principle of the official building was the central construction of the land with a cross-shaped floor plan, connecting on the floor the optimal number of four three-wing office wings to one operational center, and such partial components of these floors then mutually connect at a proportionate elevation of the building with a vertical spine of quick elevators. This is a highly economical principle, with many desirable properties otherwise unattainable, such as orientation clarity, illumination, short horizontal connections, central vertical installations, etc.; moreover, it realizes the apparent paradox of immediate connectivity while simultaneously complete separation of the four working groups at the central hall, which can have significant meaning for certain types of buildings (higher education and research institutions, hospitals, etc.) for otherwise unmanageable solutions. The described basic principle was here thought out in a large format and relatively pure architectural form and realized practically for the first time. This fact was not long understood in our country. Even less could there be understanding for such a simple thing, as that every achieved stage in something is only a precursor to the next, as this marks the developmental path of progress.

After almost thirty years since then, nothing can change the fact that there was a lack of timely opportunities to address those various tasks to which this realization logically and naturally opened a direct path. Foreign interest, significantly boosted by broad publicity and certainly also the related problems, for which solutions were sought, led to many realizations around the world, sometimes even striking replicas or forms. Domestic interest in the matter, whatever it was, largely slipped into a dead end of thoughts about a ruined Prague panorama. A smaller portion of interest, rather professional, was devoted to the VPÚ building usually in connection with the building of the Transport Enterprises in Holešovice, completed around the same time. Although it is a very significant modern building, it nonetheless lacks the basis for comparison, which could only consider the Žižkov struggle for the realization of the principles indicated above. Perhaps the merging of facts was facilitated by the fact that the building commission of the then Electric Enterprises, which based itself in many ways on similar decisions in the then VPÚ, also decided for the secondary use of the air conditioning patent Carrier and, in particular, for the ceramic cladding of the building façade with Rakodur slabs, which gave both buildings an apparent external similarity.

As for the temporary "ruin" of the Prague panorama, it was already clear to us upon the conception of the VPÚ design that the building was only the beginning of future wider construction and its component. After the completion of the building, it could be clear to anyone who considered the matter more thoroughly that the building could not be conceived as part of the already dying, charred Žižkov, but only as a component of a broader sanitary reconstruction of the future.

This situation has fundamentally not changed to this day, although a time lag has occurred, as brought about by the historical events of the last quarter-century. More detailed information about the development of the surrounding buildings of the current ROH building is provided in the book when working on this issue of Prague reconstruction, especially in a study from 1957, when Karel Honzík and I were given the opportunity to participate in a limited competition by the Ministry of Transport for partial completion of the surroundings. There we could, albeit at the cost of not adhering to the competition conditions, at least roughly fix our opinion on the necessity of solving an area much broader. Prague was fortunate that the result of this competition did not result in realization. Two years later, in 1959, I had another opportunity in our design institute to study this topic again (the study of the development of the surrounding area of the ROH building is published later).

At the end, I will add at least some data about the ROH building (former VPÚ). The construction program had further spatial requirements beyond the official building itself. Our goal was to achieve a clear arrangement of all program components. The central cross part contains about 650 office cells with axes (large module) of 3.40 m and a depth from the parapet boxes to the boxes along the central corridor of 5.80 m. These were grouped as needed into larger halls or, conversely, isolated, e.g., in the mathematics department. In addition to offices, there are smaller and larger meeting rooms in the center, a lecture hall for about 400 people, a boiler room, machine rooms, transformer stations, etc. The southern low wing contains official apartments, while we supplemented the northern wing facing Kalinin Street with rented apartments and offices on the floors; there was also a café, and on the ground floor, entirely shops, to ensure that the lively street with the construction of the official building did not become lifeless. The low construction in the open yards to the east contains garages and auxiliary facilities.

Regarding the ceramic cladding with Rakodur slabs, I note that the normal format 40 x 20 x 1.8 cm was adapted to the cladding format based on the 3.40 axis module with 8 mm joints to the format of blocks 37.7 x 19.2 x 1.8 cm. In addition, the apartments would have special blocks, e.g., corner and especially drip edges running below the window strips. The execution of the cladding was done with scientific precision and constant control. (This is detailed in the article by engineer Hineis in the publication that the journal Stavitel issued about the construction in 1935 to 1936. There are also detailed data on all components of the building's mechanical and technical equipment, especially regarding the air conditioning system.) A few remarks should be made regarding the air conditioning systems.

Some complaints have been raised over time about their proper functioning. Those that are real and do not originate solely from a certain bias usually stem from the fact that the air conditioning had to meet a variety of different requirements, sometimes even changed later (the case of the former Electric Enterprises), and here it is hard to achieve satisfactory results. A bird that has to chirp seven songs probably will not learn even one properly. Furthermore, it is essential to distinguish well so that the shortcomings of a specific installation are not attributed to the principle of the device itself; this was often done. And to reduce operational costs, especially cooling, it is necessary to utilize the principle of "longevity" — to eliminate, if possible, the consumption of active energy, which is always disproportionately higher than the energy needed to maintain operation. The mentioned publication also describes adjustments to the expansion joints, which received considerable attention, and a number of other data, which cannot be accommodated here, are elaborated on in more detail. Construction began on April 1, 1932, and was worked on until February 28, 1934, a total of 22 months. On March 1, 1934, the institute moved into the new building. With a cubic volume of 149,480 m³ of the enclosed space of all components of the building, the total construction costs, starting from the preparation and drainage of the land with all works, as well as with machinery and internal equipment, totaled approximately 64 million Kčs.

Josef Havlíček

Public Competition for the Development of the Area Surrounding the ROH Building (VPÚ)

Josef Havlíček and Emanuel Hruška, 1940

Although it was clear that no construction could take place during the war, participation in the competition was relatively large, especially given the extent of the requested works — 27 designs. The jury probably understood the overall situation and did not award any prize, but rather aimed to distribute the total available funds as rewards to almost all projects. The method of proposing and evaluating the competition is evident from the diagrams of all designs classified according to rewards in images 85 to 88. Given the local anchoring stemming from the VPÚ building design, I wanted to participate in the competition, but while working on another task, it was too broad of a task. I teamed up with Emanuel Hruška, who was in a similar situation. Karel Honzík was then ill and undergoing long-term treatment.

We published the design the same year in the publication "Towards a New Žižkov," along with considerations about the desired further development of the construction of the given area.

I will quote a few paragraphs from this publication concerning the adaptation of the development to the VPÚ building (ROH), our position on the development of the long plot C, and the open development in general. "Regarding the question: adaptation to the surroundings. Our development system consciously builds on the development system at the General Pension Institute. We proceed from the assumption that it would not be right to disregard principles that have proven their longevity in practice just because such a thing is situated right next to it. We know well certain shortcomings of the VPÚ building, but we also know that its basic operational principle is correct and has stood the test well. Adaptation is necessary not only for operational reasons but also for formal reasons and is given by the proximity of the VPÚ building. A significant number of competition designs did not realize this axiom, to which the division of the plots by Nová Street into a triangular and trapezoidal part may have contributed.

The disadvantageous triangular shape of block B is still a less serious problem than connecting the narrow plot C to the adjacent part occupied by old apartment buildings.

However, the trapezoidal plot C is only part of the block, not the entire block. The builder must have been aware of the difficulties and difficult-to-solve deficiencies for his new buildings if he is to necessarily and unfavorably influence his costly new constructions by the existing tenement developments, which already have a larger part of their lifespan behind them.

With an extraordinarily extensive construction program, of which even the competition conditions state that it is still insufficient, it is incomprehensible why the Ministry of Finance has not been shown the technical necessity of purchasing the remaining part of the block long before, which, even with demolitions, would hardly be more expensive than the price of the free plots B and C. For every building proposal for the so-called block C must parasitically utilize the free spaces behind the old apartment buildings in the remaining part of the block. This way, however, future construction sites in the remaining area become devalued, as in the places of today's old tenement houses, there is already little left for future modification, if proper ventilation is to remain and if the development of administrative buildings on the so-called block C is to be genuinely open development." In the competition, however, one had to count the plots B and C as established variables.

The so-called open development, according to the majority of the jury and apparently also the competition organizers' views, completely turns the principle of open development upside down. Where "inappropriate" surrounding construction allowed, for instance, 4 to 5 stories only around the perimeter of the plot, and the courtyard had to remain vacant, there they would simply carry out the alleged open development, i.e., almost surround the entire perimeter of the plot, but immediately to heights of 7 to 11 stories, and into the courtyard, which previously had to remain unbuilt, they would "openly" erect as many high transverse wings as could fit while maintaining a ratio of 1:1 between the wings.

It was good that the competition made this vulgar error apparent, and despite all shortcomings, it contributed to recognition of the problems. I also provide a quote from the conclusion of the publication:

"In a certain sense, the road to the new Žižkov is a road to a new Prague. We cannot restrict ourselves to just this one place, for even the mere accidental emergence of such beginnings of reconstruction would be contrary to the goal of the nascent architectural revival. Its purpose and ultimate meaning, as is the purpose of other arts, is to realize the art of living. Those office buildings in Žižkov are only part of the Žižkov quarter, which is only part of Prague, and that again is only a section of the life of the country. From architecture as the art of sealing in rotary old blocks or from architecture within the confines of mere huts in general, the evolution towards urbanism as the art of planning on solid foundations of architectural sovereignty in detail leads to a vibrant and healthy city in greenery, whose rapid transport routes are separated from pedestrian paths leading through parks, where rare monuments are cared for, and old debris is cleared away, giving way to orchards, paths, and new buildings, in which instead of neighborhoods crammed with dens, spacious residential neighborhoods breathe freely.

After two decades, we live in a state that has achieved socialism and proudly acknowledge this fact, especially in comparison with the dark period of occupation. We concluded the then publication with a postscript in which we stated the postulate of planning, planned economy — aware that these are so far words that may affect reality only after victory over German fascism. That fortune came to us five years later. In the fifteen years of further development, in which the planned economy soon became the very foundation of our state economy, much has already been achieved that previously simply seemed incredible, and much is approaching realization, what in the occupation we had to consider a dream of a distant future. Perhaps it is not even necessary to add that it absolutely does not matter that the reality has developed in some ways differently; it is clear that we could not, for example, begin with the reconstruction and completion of Žižkov while it was necessary to build industry, housing, and resolve other far more urgent tasks. However, even the construction of this significant Prague complex is beginning to ripen for inclusion in the prospective economic plan, and it will be necessary to ensure that proposals worthy of our time are studied and prepared for realization in due time.

CHARANZA, Karel. ULMAN, Jiří. Josef Havlíček - Designs and Constructions. Prague: SNTL, 1964. pp. 34-41

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

"Návrhy důstojné naší doby"

Vích

31.12.21 01:17

show all comments