Interview with Petr Kratochvíl

Historian and theoretical architect doc. PhDr. Petr Kratochvíl, CSc. returned at the end of last year from a scholarship stay at the prestigious Fulbright-Masaryk Scholarship at Columbia University. We decided to bring an interview that will shed light on current events not only on the Manhattan peninsula, where Petr Kratochvíl spent three months. Thanks to his observations and the photographs provided, you can encounter a number of valuable American buildings on the pages of the archiweb.

Departing for one of the best universities in the world must have fulfilled the dream of many academicians. How did you manage it?

The Fulbright Commission annually announces a competition for stays in the USA not only for scientists from all fields but primarily for students, which I consider particularly beneficial. Spending a semester or two at an American university at the beginning of one's career can preordain the entire future fate of a young person. Even at a more advanced age, such a stay is of course a great opportunity. The competition for a research stay assesses the submitted research project, previous results, and I am sure it helped that I had an invitation from one of the most respected theorists of architecture, Kenneth Frampton, whose A History of Modern Architecture we once translated with my colleague Halík.

American universities have long occupied a leading position in the academic world. The same goes for American schools of architecture. Don't tell me that the whole trick lies only in finances?

I don't know whether it is the quality of equipment and the height of professor salaries, or rather the prestige and concentration of intellectual capacities at select American universities, but in many fields they truly act as a magnet. After all, Professor Frampton is originally English, and for many years the dean of the School of Architecture at Columbia was the Swiss architect Bernard Tschumi, and today it is originally New Zealander Mark Wigley. Students also come from all over the world – by the way, the tuition here is 42,000 USD per year.

The theoretical ground is equally fertile in America. In Europe, the number of decent institutions could be counted on the fingers of one hand. Isn't there a risk that they might start interpreting our own history abroad?

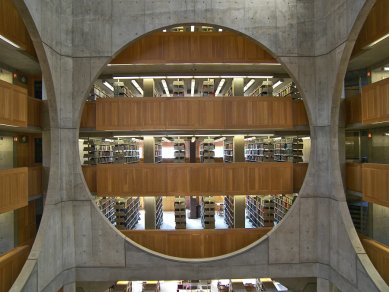

Ignasi Sola-Morales once stated that anyone wanting to study current architectural theory must go to the East Coast of the USA. I think the emphasis on the theoretical level of architecture is also indicated by the fact that of the four floors of Avery Hall, where the School of Architecture at Columbia is located, the library occupies two floors. And it is filled with students from morning till evening to the extent that you have to guard your chair when you step out for a coffee. During the critiques of student projects that I was able to attend, a lot of time is also devoted to the theoretical justification of the chosen solution – the debate around each project before the six-member committee always lasted almost an hour (and this was only a mid-semester review). Perhaps the degree of theorizing is excessive or self-serving, at least in the eyes of some architects. This would be suggested by the recent and still vivid wave of interest in neo-pragmatism, that is, the search for such theories that primarily aim at practical applicability. The term "post-critical architecture," often discussed today, which defines itself against earlier socially critical theories, is symptomatic of the same shift. But what is amazing about the USA is primarily its diversity, and each university has its own theoretical tradition, determined by key personalities. Just as in architecture itself, you will find all possible positions in its theory. And the idea that American historians would rush to explain our history seems unlikely – at that distance we are, with the exception of the personality of Václav Havel, not easily distinguishable.

I don't like hypothetical questions, but I read Mies's notes and see that America allowed him to fully develop his ideas, just as today China gives wings to Koolhaas. Could Mies be Mies without emigration?

Perhaps Mies could have developed and realized his architectural concepts within the framework of post-war recovery of Germany and Europe – his Berlin gallery is proof of that. But America offered him not only extraordinary technical means and wealthy clientele, but primarily a privileged position that he probably would not have had in Europe. With his buildings and pedagogical work, he predetermined the fundamental direction of American architecture after World War II, which then exerted its influence throughout the world.

Louis I. Kahn found more followers on his native continent. Are his ideas out of date in America and is more importance being attached to the media image?

Kahn's architecture is certainly respected as an unquestionable value, but I dare not estimate whether his ideas are considered as current and inspiring as they were during his life or later in the postmodern era. His buildings can really only be fully understood through a real visit, no matter how impressive their media representation might be. But the feeling that you become a participant in something significant in his buildings probably cannot be expressed through photographs. The harmony of forms, materials, light, and silence must be measured by your own physical presence. I must say that Kahn's galleries in New Haven and his library in Exeter were my strongest architectural experiences, even in comparison with attractive contemporary works.

From your two lectures about your American stay, it was clear that you did not spend all three months solely studying at the university or revealing all the faces of Manhattan, but you also visited the center and west of the USA. What struck you most during your travels?

A part of my stay was, of course, familiarizing myself with buildings in situ. “Never speak of a building you haven't seen with your own eyes – there will surely be someone in the audience who has,” is one of the maxims of experienced professors. So I tried to gather as much material as possible for my lectures at the Faculty of Architecture in Liberec and for my own work, and I briefly visited Boston, Chicago, Washington, and San Francisco. There are of course many remarkable buildings from both older and very recent times. Just in Manhattan, numerous large new constructions have appeared in the last 3-4 years from the likes of Gehry, Piano, Foster, Nouvel, Tschumi, and offices like Morphosis, SANAA, NL Architects, etc. In Chicago, they are trying to regain their primacy in skyscraper construction, at least regarding elegance (Jeanne Gang: Aqua Tower), while San Francisco continues to expand its collection of museums (Piano, Herzog & de Meuron, Libeskind). But beyond individual buildings, what struck me most was the attention that is now being paid to public space in these large cities. There is clearly a strong wave of new urban planning strategies, motivated even politically. It turns out that investment in the improvement or creation of new public spaces is an effective way to increase the attractiveness of the entire neighborhood and also generate profits for the city thanks to new private investments that these public spaces attract. In Boston or San Francisco, they destroyed two-story expressways that until recently cut off the city center from contact with the water, and in their place, there are now urban streets with promenades and parks. In New York, there are new bike lanes along the main avenues in Manhattan, Times Square has a partially pedestrian zone (and for the first time in history, one can sit on a bench in this heart of New York), and public parks are being created along the East River on both the Manhattan and Brooklyn shores, replacing former warehouses and industrial areas. (Nouvel completed a glass pavilion for the historic carousel here last fall.) And of course, the highlight is the High Line, an abandoned elevated railway line that has been transformed into a park-like promenade over 2 kilometers long. It is said to be the Empire State Building lying down, because just as every tourist must go up this skyscraper, today one must walk along this new north-south pedestrian axis of mid-Manhattan. And to build today at the High Line means guaranteeing a good address.

Ricardo Scofidio from DS+R is over seventy-five years old. However, significant realizations like High Line or Lincoln Center have only come to him in recent years, which has allowed him to previously work at Cooper Union and a number of scenographic projects. A similar model can be seen on the opposite coast with a whole California generation around E.O. Moss. Can a similarly unhurried start also be found in today’s hectic Europe?

The answer would require a more systematic sociological study. Some new stars of American architecture, on the contrary, are quite young – for example, Michael Arad won the competition for the (now realized) 9/11 Memorial at the age of thirty-five; and in Europe, for instance, architects who have passed through the incubator of OMA have also started their own careers quickly. Scofidio, in one interview, in fact, claims that he sees no turning point in his career because he does not distinguish between large and small projects or exhibition installations and building projects. (He reportedly only distinguishes between projects that profit and projects that lose money – and he has more of the latter.)

Chicago invented the skyscraper, and New York brought it to perfection. Other cities only copy the ideas of high-rise buildings at the cost of an uninviting ground level. Have you experienced a more pleasant life at the feet of giants anywhere else?

No. In fact, I have the feeling that skyscrapers only thrive in these two cities and are detrimental elsewhere. Boston was certainly more beautiful without them, and the skyscraper financial center of San Francisco is definitely duller than other neighborhoods, not to mention Frankfurt am Main. I considered why skyscrapers suit New York and Chicago, and I offer – without guarantee – this explanation: While in most large cities skyscrapers began to grow only after World War II and for the most part resemble similar, rather dull boxes, in Chicago and New York some of them are already over 100 years old – the panorama of these cities is therefore historically and stylistically very diverse, lively, and full of surprises when you walk through them with your head up. And secondly: Both cities have a lively ground floor. When you walk with your head down, you perceive a normal street with shops, pubs, cinemas, above which there may be 30-50 floors of office workers, but even when they go home, something usually continues to animate street life at the ground level. Those skyscrapers did not kill ordinary life on the street, as I feel it has done in London's City, but rather intensified it.

Your favorite topic is public, shared spaces. America is perceived on one hand as an individualistic country run by ruthless economic rules, but on the other hand, it is full of immensely generous patrons. Civic movements can transform the forms of cities. They do not wait for the state to decide something for them. What are your observations of public life in contemporary America?

I experienced New York just as the Occupy Wall Street movement was starting, and a small square at the lower Manhattan was occupied by camping demonstrators. Besides the basic social protest against the uneven distribution of wealth and power, it also had an interesting dimension precisely in relation to public space: What is allowed to be done in a place that is designated for the public yet regulated by many regulations and complex ownership relationships? High Line is a wonderful thing, and the structure of the abandoned railway before demolition was indeed saved by a civic initiative of enthusiasts from the neighborhood who formed the Friends of High Line society, convinced the public, then also the politicians, and today they manage this pedestrian promenade. Similarly, the feeling of safety you have at night in places like Bryant Park at 42nd Street, which was once ruled by drug dealers, has been transformed into a pleasant social and cultural space thanks to an initiative by surrounding merchants. What is called a partnership between the public and private sectors is really well utilized here. But at the same time, you feel that you are still being monitored by cameras at these places, everything that does not conform to middle-class values is subtly pushed away, and you are not sure whether this space is really public or private. Especially in the context of security measures after September 11, serious discussions have emerged about whether public space – as a place of spontaneity of expression and encounters with diversity – is not threatened or replaced by something that resembles a controlled shopping mall environment.

A light note to conclude. What did you miss the most when departing for America, and conversely, what do you miss from America after returning to the Czech Republic?

In America, I missed cafes that looked different than Starbucks. In Prague, I miss the incredibly diverse and exciting mixture of faces that you would encounter on the streets and in the subway of New York, a mixture against which we are almost all somehow the same here.

Thank you very much for the interview.

The Fulbright Commission annually announces a competition for stays in the USA not only for scientists from all fields but primarily for students, which I consider particularly beneficial. Spending a semester or two at an American university at the beginning of one's career can preordain the entire future fate of a young person. Even at a more advanced age, such a stay is of course a great opportunity. The competition for a research stay assesses the submitted research project, previous results, and I am sure it helped that I had an invitation from one of the most respected theorists of architecture, Kenneth Frampton, whose A History of Modern Architecture we once translated with my colleague Halík.

American universities have long occupied a leading position in the academic world. The same goes for American schools of architecture. Don't tell me that the whole trick lies only in finances?

I don't know whether it is the quality of equipment and the height of professor salaries, or rather the prestige and concentration of intellectual capacities at select American universities, but in many fields they truly act as a magnet. After all, Professor Frampton is originally English, and for many years the dean of the School of Architecture at Columbia was the Swiss architect Bernard Tschumi, and today it is originally New Zealander Mark Wigley. Students also come from all over the world – by the way, the tuition here is 42,000 USD per year.

The theoretical ground is equally fertile in America. In Europe, the number of decent institutions could be counted on the fingers of one hand. Isn't there a risk that they might start interpreting our own history abroad?

Ignasi Sola-Morales once stated that anyone wanting to study current architectural theory must go to the East Coast of the USA. I think the emphasis on the theoretical level of architecture is also indicated by the fact that of the four floors of Avery Hall, where the School of Architecture at Columbia is located, the library occupies two floors. And it is filled with students from morning till evening to the extent that you have to guard your chair when you step out for a coffee. During the critiques of student projects that I was able to attend, a lot of time is also devoted to the theoretical justification of the chosen solution – the debate around each project before the six-member committee always lasted almost an hour (and this was only a mid-semester review). Perhaps the degree of theorizing is excessive or self-serving, at least in the eyes of some architects. This would be suggested by the recent and still vivid wave of interest in neo-pragmatism, that is, the search for such theories that primarily aim at practical applicability. The term "post-critical architecture," often discussed today, which defines itself against earlier socially critical theories, is symptomatic of the same shift. But what is amazing about the USA is primarily its diversity, and each university has its own theoretical tradition, determined by key personalities. Just as in architecture itself, you will find all possible positions in its theory. And the idea that American historians would rush to explain our history seems unlikely – at that distance we are, with the exception of the personality of Václav Havel, not easily distinguishable.

I don't like hypothetical questions, but I read Mies's notes and see that America allowed him to fully develop his ideas, just as today China gives wings to Koolhaas. Could Mies be Mies without emigration?

Perhaps Mies could have developed and realized his architectural concepts within the framework of post-war recovery of Germany and Europe – his Berlin gallery is proof of that. But America offered him not only extraordinary technical means and wealthy clientele, but primarily a privileged position that he probably would not have had in Europe. With his buildings and pedagogical work, he predetermined the fundamental direction of American architecture after World War II, which then exerted its influence throughout the world.

Louis I. Kahn found more followers on his native continent. Are his ideas out of date in America and is more importance being attached to the media image?

Kahn's architecture is certainly respected as an unquestionable value, but I dare not estimate whether his ideas are considered as current and inspiring as they were during his life or later in the postmodern era. His buildings can really only be fully understood through a real visit, no matter how impressive their media representation might be. But the feeling that you become a participant in something significant in his buildings probably cannot be expressed through photographs. The harmony of forms, materials, light, and silence must be measured by your own physical presence. I must say that Kahn's galleries in New Haven and his library in Exeter were my strongest architectural experiences, even in comparison with attractive contemporary works.

From your two lectures about your American stay, it was clear that you did not spend all three months solely studying at the university or revealing all the faces of Manhattan, but you also visited the center and west of the USA. What struck you most during your travels?

A part of my stay was, of course, familiarizing myself with buildings in situ. “Never speak of a building you haven't seen with your own eyes – there will surely be someone in the audience who has,” is one of the maxims of experienced professors. So I tried to gather as much material as possible for my lectures at the Faculty of Architecture in Liberec and for my own work, and I briefly visited Boston, Chicago, Washington, and San Francisco. There are of course many remarkable buildings from both older and very recent times. Just in Manhattan, numerous large new constructions have appeared in the last 3-4 years from the likes of Gehry, Piano, Foster, Nouvel, Tschumi, and offices like Morphosis, SANAA, NL Architects, etc. In Chicago, they are trying to regain their primacy in skyscraper construction, at least regarding elegance (Jeanne Gang: Aqua Tower), while San Francisco continues to expand its collection of museums (Piano, Herzog & de Meuron, Libeskind). But beyond individual buildings, what struck me most was the attention that is now being paid to public space in these large cities. There is clearly a strong wave of new urban planning strategies, motivated even politically. It turns out that investment in the improvement or creation of new public spaces is an effective way to increase the attractiveness of the entire neighborhood and also generate profits for the city thanks to new private investments that these public spaces attract. In Boston or San Francisco, they destroyed two-story expressways that until recently cut off the city center from contact with the water, and in their place, there are now urban streets with promenades and parks. In New York, there are new bike lanes along the main avenues in Manhattan, Times Square has a partially pedestrian zone (and for the first time in history, one can sit on a bench in this heart of New York), and public parks are being created along the East River on both the Manhattan and Brooklyn shores, replacing former warehouses and industrial areas. (Nouvel completed a glass pavilion for the historic carousel here last fall.) And of course, the highlight is the High Line, an abandoned elevated railway line that has been transformed into a park-like promenade over 2 kilometers long. It is said to be the Empire State Building lying down, because just as every tourist must go up this skyscraper, today one must walk along this new north-south pedestrian axis of mid-Manhattan. And to build today at the High Line means guaranteeing a good address.

Ricardo Scofidio from DS+R is over seventy-five years old. However, significant realizations like High Line or Lincoln Center have only come to him in recent years, which has allowed him to previously work at Cooper Union and a number of scenographic projects. A similar model can be seen on the opposite coast with a whole California generation around E.O. Moss. Can a similarly unhurried start also be found in today’s hectic Europe?

The answer would require a more systematic sociological study. Some new stars of American architecture, on the contrary, are quite young – for example, Michael Arad won the competition for the (now realized) 9/11 Memorial at the age of thirty-five; and in Europe, for instance, architects who have passed through the incubator of OMA have also started their own careers quickly. Scofidio, in one interview, in fact, claims that he sees no turning point in his career because he does not distinguish between large and small projects or exhibition installations and building projects. (He reportedly only distinguishes between projects that profit and projects that lose money – and he has more of the latter.)

Chicago invented the skyscraper, and New York brought it to perfection. Other cities only copy the ideas of high-rise buildings at the cost of an uninviting ground level. Have you experienced a more pleasant life at the feet of giants anywhere else?

No. In fact, I have the feeling that skyscrapers only thrive in these two cities and are detrimental elsewhere. Boston was certainly more beautiful without them, and the skyscraper financial center of San Francisco is definitely duller than other neighborhoods, not to mention Frankfurt am Main. I considered why skyscrapers suit New York and Chicago, and I offer – without guarantee – this explanation: While in most large cities skyscrapers began to grow only after World War II and for the most part resemble similar, rather dull boxes, in Chicago and New York some of them are already over 100 years old – the panorama of these cities is therefore historically and stylistically very diverse, lively, and full of surprises when you walk through them with your head up. And secondly: Both cities have a lively ground floor. When you walk with your head down, you perceive a normal street with shops, pubs, cinemas, above which there may be 30-50 floors of office workers, but even when they go home, something usually continues to animate street life at the ground level. Those skyscrapers did not kill ordinary life on the street, as I feel it has done in London's City, but rather intensified it.

Your favorite topic is public, shared spaces. America is perceived on one hand as an individualistic country run by ruthless economic rules, but on the other hand, it is full of immensely generous patrons. Civic movements can transform the forms of cities. They do not wait for the state to decide something for them. What are your observations of public life in contemporary America?

I experienced New York just as the Occupy Wall Street movement was starting, and a small square at the lower Manhattan was occupied by camping demonstrators. Besides the basic social protest against the uneven distribution of wealth and power, it also had an interesting dimension precisely in relation to public space: What is allowed to be done in a place that is designated for the public yet regulated by many regulations and complex ownership relationships? High Line is a wonderful thing, and the structure of the abandoned railway before demolition was indeed saved by a civic initiative of enthusiasts from the neighborhood who formed the Friends of High Line society, convinced the public, then also the politicians, and today they manage this pedestrian promenade. Similarly, the feeling of safety you have at night in places like Bryant Park at 42nd Street, which was once ruled by drug dealers, has been transformed into a pleasant social and cultural space thanks to an initiative by surrounding merchants. What is called a partnership between the public and private sectors is really well utilized here. But at the same time, you feel that you are still being monitored by cameras at these places, everything that does not conform to middle-class values is subtly pushed away, and you are not sure whether this space is really public or private. Especially in the context of security measures after September 11, serious discussions have emerged about whether public space – as a place of spontaneity of expression and encounters with diversity – is not threatened or replaced by something that resembles a controlled shopping mall environment.

A light note to conclude. What did you miss the most when departing for America, and conversely, what do you miss from America after returning to the Czech Republic?

In America, I missed cafes that looked different than Starbucks. In Prague, I miss the incredibly diverse and exciting mixture of faces that you would encounter on the streets and in the subway of New York, a mixture against which we are almost all somehow the same here.

Thank you very much for the interview.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Veřejný prostor je zajímavé téma.

robert

22.02.12 09:38

show all comments