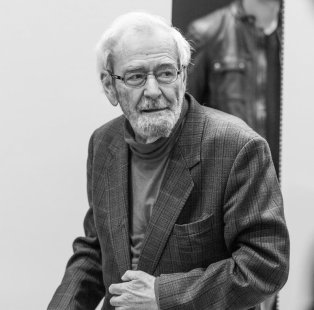

Memory of Pavel Halík

Source

Mgr. Ondřej Váša, Ph.D.

Mgr. Ondřej Váša, Ph.D.

Publisher

Tisková zpráva

16.07.2021 11:40

Tisková zpráva

16.07.2021 11:40

Czech Republic

Prague

Kobylisy

Pavel Halík

On Monday, June 21, 2021, at the age of 85, the historian of architecture doc. Ing. arch. Pavel Halík, CSc. passed away, whose professional life was closely connected with the Institute of Art History of the Czech Academy of Sciences and the Faculty of Architecture at the Technical University of Liberec. Together with Prof. Petr Kratochvíl, he contributed to the popularization of contemporary architecture and translated essential books by theorists Christian Norberg-Schulz and Kenneth Frampton for the Czech audience. A link to the obituary written for the Slovak magazine Architektúra & Urbanizmus.

In my notebook, I found a note that I took from Pavel perhaps about a month ago, which I do not understand. It reads: “What will they remember in old age and what will they tell each other?” And above that, a single word: wandering. I know that Pavel spoke then about modern train stations as modern temples, which offer a connection to the world instead of to God. He also talked about judicial palaces, banks, and hotels (which are, in fact, like banks of people), and how these typical monuments of the 19th century—perhaps in contrast to Giotto's chapel in Padua—are transfer stations that replace ecclesiastical gatherings with a bustling distribution. Yet I still cannot remember what old age and memories were being discussed. Did it concern the communicability of houses and facades, or perhaps the memories of people wandering through city streets like unchewed morsels? I don’t know.

That day, in any case, I would like to rewind and play it again, just as Pavel often replayed conversations and scenes from the films of Wim Wenders, Luis Buñuel, Federico Fellini, or Terrence Malick over the past year.

So stop, rewind, play: it is an early summer afternoon, an unnamed ordinary day that slipped from the calendar. Pavel is sitting in his room with a window overlooking a small garden with an apple tree; on the windowsill, like at an improvised airfield, models of Spitfires, Fokkers, and Avians are bustling, which he eagerly discussed as if they were distinctive form poems. Before him, a digital window wide open with a view of the galaxies of modern metropolises; somewhere around is hiding T. S. Eliot, whom we cannot find, and whose Four Quartets he ends up reciting from memory. And he throws in a few brisk comments with his characteristic shining eyes and sly smile, as always when he could share his brilliant observations with someone.

He often did this, and for many of us, he acted like a generous hearth from which unusual sparks flew into the darkness. Pavel loved conversations, and his figurative collages and series, through which he tried to capture unexpected connections and hidden poetry of cities— which he never ceased to develop— grew into such a sophisticated and well-thought-out system that it can be compared to the canonical atlas of Mnemosyne by Aby Warburg. These were his ways of conversing with houses and cities, of which he was simultaneously a unique storyteller and friend, with an exceptional talent for perceiving the formal language of human figures, buildings, and airplanes.

In fact, it is characteristic that the question “what will they remember in old age and what will they tell each other?” can pertain to houses, facades, and people alike, for only he who can be a friend to things—a friend to the world, as Pavel was—can perceive it as friendly and also demand friendship from it. This is then an idea that Pavel and I returned to again and again, and which Pavel—not only deepening it into a distinctive theoretical position, but living it intensely— embodied, as a true humanist philosopher of architecture, though he would never label himself as such.

Cut. It is the spring of 2019, and Pavel enters the Medici Chapel in Florence for the first time in his life, which he perceived along with the anteroom of the Laurentian Library as a place of compressed forces, like a kind of nuclear reactors, from whose energy entire subsequent centuries drew. And suddenly, tears well up in his eyes. Because the Medici Chapel was not just a monument for Pavel, but an intensely intimate space that he faced with characteristic pride, the additional dimension of which is precisely humility and tenderness. And I cannot help but respectfully repeat—for all of us who could learn from him in this regard—that it was through the prism of this tender pride that he uniquely understood architecture, just as he embodied it with the same characteristic elegance and flair that remained with him until the very end.

But let’s return to Pavel's room, just on another day sometime in early spring, when we might catch Pavel admiring the Reims Cathedral as “a land that reaches for the sky.” Immediately as a welcome, he poses a rhetorical question that subtly captures his Renaissance nature: “Where has the sky gone above modern cities?” It is no coincidence that our joint digital walks through modern and contemporary cities often began and ended in Santini's Church of St. John of Nepomuk in Žďár nad Sázavou, not at all because Pavel grew up near this temple. While Pavel’s enthusiasm for avant-garde hedonism was his own, and he loved the world from a human perspective, it was as if he sometimes unveiled an equally significant sentiment for “heavenly things,” such as when he remarked that Le Corbusier, despite all his talent, was merely a “materialist,” because “to become a Michelangelo, he would have to think about eternity and divinity.”

Pavel did so; thus, if I say goodbye for all of us, my friend, then not only do we fulfill one of his wishes, but at the same time, we cross the horizontal of his loving and passionately human life with the vertical of his humility. So: to God, my friend!

That day, in any case, I would like to rewind and play it again, just as Pavel often replayed conversations and scenes from the films of Wim Wenders, Luis Buñuel, Federico Fellini, or Terrence Malick over the past year.

So stop, rewind, play: it is an early summer afternoon, an unnamed ordinary day that slipped from the calendar. Pavel is sitting in his room with a window overlooking a small garden with an apple tree; on the windowsill, like at an improvised airfield, models of Spitfires, Fokkers, and Avians are bustling, which he eagerly discussed as if they were distinctive form poems. Before him, a digital window wide open with a view of the galaxies of modern metropolises; somewhere around is hiding T. S. Eliot, whom we cannot find, and whose Four Quartets he ends up reciting from memory. And he throws in a few brisk comments with his characteristic shining eyes and sly smile, as always when he could share his brilliant observations with someone.

He often did this, and for many of us, he acted like a generous hearth from which unusual sparks flew into the darkness. Pavel loved conversations, and his figurative collages and series, through which he tried to capture unexpected connections and hidden poetry of cities— which he never ceased to develop— grew into such a sophisticated and well-thought-out system that it can be compared to the canonical atlas of Mnemosyne by Aby Warburg. These were his ways of conversing with houses and cities, of which he was simultaneously a unique storyteller and friend, with an exceptional talent for perceiving the formal language of human figures, buildings, and airplanes.

In fact, it is characteristic that the question “what will they remember in old age and what will they tell each other?” can pertain to houses, facades, and people alike, for only he who can be a friend to things—a friend to the world, as Pavel was—can perceive it as friendly and also demand friendship from it. This is then an idea that Pavel and I returned to again and again, and which Pavel—not only deepening it into a distinctive theoretical position, but living it intensely— embodied, as a true humanist philosopher of architecture, though he would never label himself as such.

Cut. It is the spring of 2019, and Pavel enters the Medici Chapel in Florence for the first time in his life, which he perceived along with the anteroom of the Laurentian Library as a place of compressed forces, like a kind of nuclear reactors, from whose energy entire subsequent centuries drew. And suddenly, tears well up in his eyes. Because the Medici Chapel was not just a monument for Pavel, but an intensely intimate space that he faced with characteristic pride, the additional dimension of which is precisely humility and tenderness. And I cannot help but respectfully repeat—for all of us who could learn from him in this regard—that it was through the prism of this tender pride that he uniquely understood architecture, just as he embodied it with the same characteristic elegance and flair that remained with him until the very end.

But let’s return to Pavel's room, just on another day sometime in early spring, when we might catch Pavel admiring the Reims Cathedral as “a land that reaches for the sky.” Immediately as a welcome, he poses a rhetorical question that subtly captures his Renaissance nature: “Where has the sky gone above modern cities?” It is no coincidence that our joint digital walks through modern and contemporary cities often began and ended in Santini's Church of St. John of Nepomuk in Žďár nad Sázavou, not at all because Pavel grew up near this temple. While Pavel’s enthusiasm for avant-garde hedonism was his own, and he loved the world from a human perspective, it was as if he sometimes unveiled an equally significant sentiment for “heavenly things,” such as when he remarked that Le Corbusier, despite all his talent, was merely a “materialist,” because “to become a Michelangelo, he would have to think about eternity and divinity.”

Pavel did so; thus, if I say goodbye for all of us, my friend, then not only do we fulfill one of his wishes, but at the same time, we cross the horizontal of his loving and passionately human life with the vertical of his humility. So: to God, my friend!

Ondřej Váša

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment