The sanitation of the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries fundamentally changed the face of Prague

|

After Vienna, the then second largest city of the Habsburg monarchy, the Royal Capital Prague was formed in February 1784 by merging the Old Town, Lesser Town, Hradčany, and New Town. In 1850, Josefov, the notorious fifth district (originally the Jewish Town), was added to the city, followed by Vyšehrad in 1883 and Holešovice and Bubny a year later. The city had about half a million inhabitants.

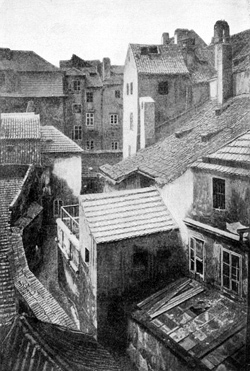

The main motive behind one of the largest urban sanitations in Europe, which caused considerable outrage at the time, was primarily the construction and hygienic neglect of Josefov (overpopulation, non-existence of sewage systems, easy possibility of infection), but also a certain "lack of representation" of Josefov near the Old Town Square.

Preparations began as early as 1882, and the laws came into effect on April 7, 1893. There were two laws, the first of which delineated the boundaries of the sanitation zones and conferred expropriation rights to the city for ten years, while the second exempted new buildings from rental tax for 20 years.

In the sanitation zones, covering an area of over 380,000 m², there were 608 houses divided into two parts. The first was the sanitation zone of Josefov and the Old Town, bordered roughly by the Vltava River, Revoluční Street (then Eliščina), Dlouhá Street, and Platnéřská Street, covering more than 365,000 m², where 584 houses were to be demolished. The second, smaller sanitation area of the New Town, delimited by the Vltava River and Ostrovní, Pštrossova, and Myslíkova Streets, had over 14,000 m²; 18 houses were to be demolished there.

Partial demolitions began in 1895, with massive tearing down taking place from October 1896. By 1903, 150 houses had been demolished and 67 new constructions built. The sanitation laws were set to last only ten years, but in April 1903, they were extended for another ten, which was repeated in 1913, 1923, and 1933, with validity until April 7, 1943. The largest interventions took place before 1914: by that year, a total of 469 houses had been demolished, including 247 in Josefov, 198 in the Old Town, and 24 in the New Town. Sanitation activities stagnated during the First and Second World Wars and in the 1920s and 1930s were concentrated only on the eastern edge of the Old Town sanitation zone.

During the sanitation, three of the nine synagogues in Josefov had to surrender: the New Synagogue from the late 16th century, which stood on what is now Široká Street, was demolished in 1898; the Great Dvor Synagogue from the early 17th century, which was located at the end of today's Paris Street on the site of the current space in front of the Intercontinental Hotel, was demolished in 1902; and the Cikán Synagogue from 1613 on Bílková Street was demolished in 1906. In response to these destructions, the Jubilee Synagogue was built on Jerusalem Street in 1906. In 1903, the ancient Jewish cemetery in Josefov was also reduced.

Other buildings that were demolished include the House of Jiří Melantrich from Aventin (known as At Two Camels) on the current Melantrichova Street, which was torn down in 1893 (only the portal remained), the baroque Benedictine monastery at St. Nicholas Church in the Old Town Square, which was demolished in 1902 (a neo-baroque building from 1903 now stands in its place), and the so-called Krenn House, which blocked the view of St. Nicholas Church from the Old Town Square. Streets such as Rabbi, Meislova, Střelná, Červená, or Masařská also disappeared.

However, the sanitation plans eventually faced opposition from the public and elites. The first memento was the demolition of the beautiful burgher house of Jiří Melantrich with its Renaissance façade and picturesque loggia in the courtyard.

The so-called Easter Manifesto from April 1896, written by the author Vilém Mrštík, was a literal eruption. It stated that Prague was "being stealthily stripped of its most precious gem, its historical picturesque character, and it was halted by dull apartment buildings of such a loathsome taste that one feels embarrassed to publicly admit to it". Many well-known personalities signed the manifesto, including writers Alois Jirásek, Otokar Březina, F. X. Šalda, painters Mikoláš Aleš and Josef Václav Myslbek, as well as a number of scientists, politicians, and other notable figures.

In Mrštík's further scathing condemnation of the ignorance of the then Prague councillors and the architects of sanitation, titled "Bestia Triumphans," a name borrowed from the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, he concluded: "The lower the conscience, the more blindly vice rages; the more frail the education, the more illustrious feasts the principal enemy - bestia triumphans - prepares for itself."

Afterwards, the sanitation advanced more cautiously, and public pressure helped to save numerous monuments. The newly constructed buildings represented a high standard for their time. What was once a poor "medieval" district transformed into a luxurious zone of Art Nouveau houses.

Throughout the 20th century, other, albeit less pronounced, sanitations garnered public attention. For example, the demolition of the neo-Renaissance railway station at Prague's Těšnov in connection with the construction of the North-South Expressway in March 1985 became a symbol of the insensitive approach of the then Communist authorities towards monuments. Protests were also raised against the construction of the television tower in Žižkov or the sanitation of half of Žižkov in the 1980s, as well as the demolition of the Špaček House between Klimentská and Mlynářská Streets in 1993.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment