Tea House - History

At the beginning of my brief research, I would like to emphasize once again that from my perspective, this is a personal free interpretation of the theme of minimal space for meeting rather than an orthodox tea house. After all, the agreement in the impartial view of the topic between myself and Professor Fujimori was the main impulse behind my decision for the design and its entire execution. Our conversation on this topic is also recorded in written form. As part of my thesis, I have prepared a brief theoretical section dealing with the traditional conception of the tea ceremony and the journey of tea to the Japanese continent.

The tea house represents a traditional type of building in wooden Japanese architecture, which typologically established itself almost four hundred years ago. The extraordinary event of visiting a tea house always offered guests the opportunity to enjoy a calm atmosphere, not only of the tea house itself but also of the place in which the tea house was located. The location was always carefully chosen with the aim of allowing guests to free their minds from everyday worries and to fully meditate on the green tea. The history of tea houses and the journey of tea is very rich, so I will attempt to provide a very brief introduction primarily from the field of Japan.

During the Asuka period (593-710), tea grown in China was brought to Japan from Korea for the first time. However, tea drinking did not take hold at that time, and tea as such quickly disappeared from the Japanese islands. In 1191, however, tea returned to Japan thanks to Zen monk Eisai, who was studying in China at that time and brought back several tea seeds, from which he successfully cultivated tea plants around his monastery in the Kyoto area. This period can be considered the beginning of tea culture in Japan.

The effects of theine contained in green tea were indispensable for the Zen monks, who indulged in meditation and were the largest consumers of tea harvests from their own tea plantations at that time. The method of preparing tea in monasteries was different from common Western methods, as the tea leaves were ground into a fine green powder, which is still called Matcha and today represents the highest grade of green tea. Matcha was prepared in hot water, and the ritual accompanying the entire preparation was called "Cha no you," which means tea ceremony.

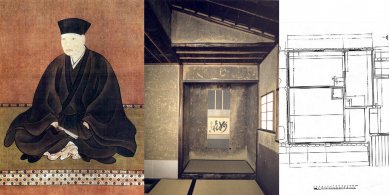

One of the main masters of the tea ceremony is considered to be Master Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591), who actively practiced the tea ceremony until his lord, the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi, ordered him to commit ritual suicide (seppuku). There are ongoing debates about the warlord's decision. Sen no Rikyū firmly established not only the rules of the entire ritual during his time but also focused on architecture and the design of tea utensils, which he brought to absolute perfection. After his death, several schools dedicated themselves to the tea ceremony, some of which still exist today.

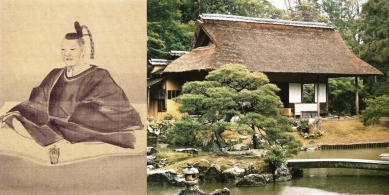

According to Master Sen no Rikyū, a tea house or tea room should adhere to specific rules, one of which is the selection of location, which determines its construction and appearance. A tea house is usually situated in a garden that serves as the entrance to the house itself. Passing through the path "roji," the world of everyday concerns symbolically closes behind the guests. An essential part of the interior of the tea room is a hearth as a symbol of life, along with a small entrance, as every visitor must bow their head upon entering, lay down their weapon, and thus express their humility. A classic tea room should also include a Tokonama - a sacred alcove for placing a work of art, which can be a source for subsequent conversation. The materials for building a tea house are chosen with utmost care.

Since the time when monks in Zen monasteries around Kyoto began to cultivate tea until the aforementioned Master Sen no Rikyū, the way tea was consumed has changed several times. One of the greatest revolutions occurred during the Muromachi period when its popularity spread among the samurai, who were, on one hand, fierce warriors, but on the other hand, also actively engaged in art and poetry.

At that time, the samurai held social gatherings to demonstrate their social status, of which drinking tea was an integral part. However, as tea became integrated into everyday social pleasures, it gradually lost its spirituality and became part of entertainment. One well-known event was the holding of the so-called Tocha, a type of gambling game in which the samurai also participated, and during which tea was again consumed. In this way, tea gradually spread among all classes and also popularized art, as the subjects of bets in Tocha were typically various art objects.

At the same time, small huts, called Tori (hermitages), began to emerge on the outskirts of cities or in secluded places, where special attention and care were dedicated to tea preparation. Over time, these huts began to slowly move to the gardens of noble estates, and their size was standardized to the dimensions of 4.5 tatami. The relocation of Tori to private property was a turning point in the history of tea houses.

SEN NO RIKYU

It was precisely during the period when tea houses began to be transferred to private gardens that Master Sen no Rikyū lived, who dedicated his entire life to tea and who transformed the tea ceremony into a form of avant-garde expression of a politically charged act, distant from established conventions. When he invited his lord and contemporary warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi to his tea house, who had to remove his shoes and lay aside his sword before entering, he demonstrated that at this extraordinary meeting during the tea drinking, both were equals. This suppressed the otherwise strict social hierarchy.

Sen no Rikyū began with various innovations in tea space. This involved the search for spatial minimization while maintaining a unique atmosphere. The small entrance not only expressed humility but also refined the impression of a large space inside.

One of his highly regarded minimal tea rooms is Tai-an Myoki-an in Kyoto. Its space consists of only two tatami and a very small entrance of approximately 79x72 cm. Rikyū also engaged in the production of tea utensils, for example, he made the chawan with his own hands and treated it with black color, he crafted the chashaku or tea spoon from bamboo, etc. Many of his designs are still considered perfect and almost unbeatable today. In his time, he was a very remarkable model of a comprehensive approach in tea culture.

TEA CULTURE AND TEA ARCHITECTURE TODAY

The tea ceremony retains its tradition in several Japanese tea schools, of which the most famous is probably the Urasenke school, founded by one of the descendants of Sen no Rikyū and which has many years of experience in training tea masters to this day. In the 19th century, the right to learn the tea ceremony was also granted to women thanks to the progressive strength of the Urasenke school. Throughout the 20th century, the practice of tea ceremonies largely shifted to women, who currently make up the majority of participants and masters of tea ceremonies. However, currently, only a narrow group of people in Japan devote themselves to the tea ceremony, and many know little more about it than we do. It can be said that as a result of all the world events of the 20th century and the flood of Western culture, the tea ceremony began to slowly disappear from the Japanese islands.

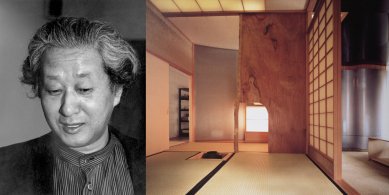

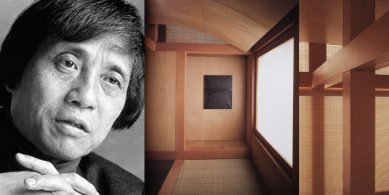

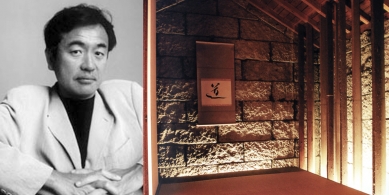

Its influence is evident not only in architecture and aesthetics but also in social etiquette. In the 1970s, a new wave of architects emerged, such as Arata Isozaki, Tadao Ando, and Terunobu Fujimori, who again began to focus on the architecture of tea houses. Today, the tea house remains a significant challenge for Japanese architects, especially from the perspective of spatial minimization.

SOURCES

Jiří Škabrada, Folk Architecture, Argo, 1999

Maric Macubara - Traditional Japanese architecture and design, Brutus Casa, 2006, pp. 063-074

Heino Engel, Measure and construction of the Japanese house, Tuttle publishing, 1985

Arata Isozaki, Tadao Ando, Terunobu Fujimori, The contemporary tea house, Kodansha International, 2007

Soňa, Zdeněk, and Michal Thom, The Story of Tea, Argo, 2005

Sóšicu Sen, Čadó Japonská cesta čaje, Pragma, 1999

Stacey B. Day, Kijoši Inokuči, The Wisdom of Samurai, 1998

Kakuzó Okakura, The Book of Tea, Brody Publishing, 1998

H. Byron Earhart, Religion in Japan, Prostor, 1998

Master Lu Ju, Classic Book of Tea, DharmaGaia, 2002

Hirai Kiyosi, The Japanese house than and now, Ichgaya Publications, 1998

Manjóšú, Ten Thousand Leaves from Ancient Japan, Brody, 2003 - translated by Antonín Líman

The tea house represents a traditional type of building in wooden Japanese architecture, which typologically established itself almost four hundred years ago. The extraordinary event of visiting a tea house always offered guests the opportunity to enjoy a calm atmosphere, not only of the tea house itself but also of the place in which the tea house was located. The location was always carefully chosen with the aim of allowing guests to free their minds from everyday worries and to fully meditate on the green tea. The history of tea houses and the journey of tea is very rich, so I will attempt to provide a very brief introduction primarily from the field of Japan.

During the Asuka period (593-710), tea grown in China was brought to Japan from Korea for the first time. However, tea drinking did not take hold at that time, and tea as such quickly disappeared from the Japanese islands. In 1191, however, tea returned to Japan thanks to Zen monk Eisai, who was studying in China at that time and brought back several tea seeds, from which he successfully cultivated tea plants around his monastery in the Kyoto area. This period can be considered the beginning of tea culture in Japan.

The effects of theine contained in green tea were indispensable for the Zen monks, who indulged in meditation and were the largest consumers of tea harvests from their own tea plantations at that time. The method of preparing tea in monasteries was different from common Western methods, as the tea leaves were ground into a fine green powder, which is still called Matcha and today represents the highest grade of green tea. Matcha was prepared in hot water, and the ritual accompanying the entire preparation was called "Cha no you," which means tea ceremony.

One of the main masters of the tea ceremony is considered to be Master Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591), who actively practiced the tea ceremony until his lord, the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi, ordered him to commit ritual suicide (seppuku). There are ongoing debates about the warlord's decision. Sen no Rikyū firmly established not only the rules of the entire ritual during his time but also focused on architecture and the design of tea utensils, which he brought to absolute perfection. After his death, several schools dedicated themselves to the tea ceremony, some of which still exist today.

According to Master Sen no Rikyū, a tea house or tea room should adhere to specific rules, one of which is the selection of location, which determines its construction and appearance. A tea house is usually situated in a garden that serves as the entrance to the house itself. Passing through the path "roji," the world of everyday concerns symbolically closes behind the guests. An essential part of the interior of the tea room is a hearth as a symbol of life, along with a small entrance, as every visitor must bow their head upon entering, lay down their weapon, and thus express their humility. A classic tea room should also include a Tokonama - a sacred alcove for placing a work of art, which can be a source for subsequent conversation. The materials for building a tea house are chosen with utmost care.

Since the time when monks in Zen monasteries around Kyoto began to cultivate tea until the aforementioned Master Sen no Rikyū, the way tea was consumed has changed several times. One of the greatest revolutions occurred during the Muromachi period when its popularity spread among the samurai, who were, on one hand, fierce warriors, but on the other hand, also actively engaged in art and poetry.

At that time, the samurai held social gatherings to demonstrate their social status, of which drinking tea was an integral part. However, as tea became integrated into everyday social pleasures, it gradually lost its spirituality and became part of entertainment. One well-known event was the holding of the so-called Tocha, a type of gambling game in which the samurai also participated, and during which tea was again consumed. In this way, tea gradually spread among all classes and also popularized art, as the subjects of bets in Tocha were typically various art objects.

At the same time, small huts, called Tori (hermitages), began to emerge on the outskirts of cities or in secluded places, where special attention and care were dedicated to tea preparation. Over time, these huts began to slowly move to the gardens of noble estates, and their size was standardized to the dimensions of 4.5 tatami. The relocation of Tori to private property was a turning point in the history of tea houses.

SEN NO RIKYU

It was precisely during the period when tea houses began to be transferred to private gardens that Master Sen no Rikyū lived, who dedicated his entire life to tea and who transformed the tea ceremony into a form of avant-garde expression of a politically charged act, distant from established conventions. When he invited his lord and contemporary warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi to his tea house, who had to remove his shoes and lay aside his sword before entering, he demonstrated that at this extraordinary meeting during the tea drinking, both were equals. This suppressed the otherwise strict social hierarchy.

Sen no Rikyū began with various innovations in tea space. This involved the search for spatial minimization while maintaining a unique atmosphere. The small entrance not only expressed humility but also refined the impression of a large space inside.

One of his highly regarded minimal tea rooms is Tai-an Myoki-an in Kyoto. Its space consists of only two tatami and a very small entrance of approximately 79x72 cm. Rikyū also engaged in the production of tea utensils, for example, he made the chawan with his own hands and treated it with black color, he crafted the chashaku or tea spoon from bamboo, etc. Many of his designs are still considered perfect and almost unbeatable today. In his time, he was a very remarkable model of a comprehensive approach in tea culture.

TEA CULTURE AND TEA ARCHITECTURE TODAY

The tea ceremony retains its tradition in several Japanese tea schools, of which the most famous is probably the Urasenke school, founded by one of the descendants of Sen no Rikyū and which has many years of experience in training tea masters to this day. In the 19th century, the right to learn the tea ceremony was also granted to women thanks to the progressive strength of the Urasenke school. Throughout the 20th century, the practice of tea ceremonies largely shifted to women, who currently make up the majority of participants and masters of tea ceremonies. However, currently, only a narrow group of people in Japan devote themselves to the tea ceremony, and many know little more about it than we do. It can be said that as a result of all the world events of the 20th century and the flood of Western culture, the tea ceremony began to slowly disappear from the Japanese islands.

Its influence is evident not only in architecture and aesthetics but also in social etiquette. In the 1970s, a new wave of architects emerged, such as Arata Isozaki, Tadao Ando, and Terunobu Fujimori, who again began to focus on the architecture of tea houses. Today, the tea house remains a significant challenge for Japanese architects, especially from the perspective of spatial minimization.

SOURCES

Jiří Škabrada, Folk Architecture, Argo, 1999

Maric Macubara - Traditional Japanese architecture and design, Brutus Casa, 2006, pp. 063-074

Heino Engel, Measure and construction of the Japanese house, Tuttle publishing, 1985

Arata Isozaki, Tadao Ando, Terunobu Fujimori, The contemporary tea house, Kodansha International, 2007

Soňa, Zdeněk, and Michal Thom, The Story of Tea, Argo, 2005

Sóšicu Sen, Čadó Japonská cesta čaje, Pragma, 1999

Stacey B. Day, Kijoši Inokuči, The Wisdom of Samurai, 1998

Kakuzó Okakura, The Book of Tea, Brody Publishing, 1998

H. Byron Earhart, Religion in Japan, Prostor, 1998

Master Lu Ju, Classic Book of Tea, DharmaGaia, 2002

Hirai Kiyosi, The Japanese house than and now, Ichgaya Publications, 1998

Manjóšú, Ten Thousand Leaves from Ancient Japan, Brody, 2003 - translated by Antonín Líman

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment