Pavel Janák: Prism and Pyramid

The spans and movements of our domestic architecture have been and are defined by both major families of European architecture: southern antique and northern Christian. Both represent in our view two possibilities of artistic style that could have arisen in the territory of our conceptual world and with its mental dispositions. They are the two most distant poles (considering the purest representative types: Greece and French Gothic around 1300) that art has found: the architecture of the southern group is - despite its high style - a kind of naturalism in architecture, as it relies on a natural way of building (placing stones on top of each other): it leaves the structural units (columns, beams) with wholly independent natures, a prismatic surface, and mass, and beautifies them only with beautifully processed and proportionally arranged stones and slabs: it places these heavy stones quietly and silently upon each other according to the simplest natural law of weight in a manner that says nothing about the pressures and forces they bear and transfer. A fundamental characteristic of this southern architecture is that even where it forms large masses (Egypt, Rome), and thus somewhat more casually concerning structural units, it still retains the character of layered building. The northern group moves from earthly building to the beauty of the supernatural; the structural units (stones) disappear beneath the entirety of the building, and conversely, one penetrates into the mass of the stone, boldly and speculatively taking from its surface material; the goal is a building seemingly made from a singular mass, with all its parts alive and active, even tense. The southern current, with its clear naturalism and generality, has always been capable of new transplants and graftings: therefore, so many times from Egypt and Asia to the recent Renaissance endeavors of the 19th century, it has rooted itself in the widest geographical and temporal areas and revitalized the fading era with the simplicity of its creative principles. However, the northern group, as soon as its sources became liberated by Romanesque styles, developed and exhausted itself in a direct path of a singular style, because its ultimate goal - the complete transcendence of matter - was so specific and thus unattainable that long before it, it had to stop at a certain limit defined by matter itself. Once again, however, in history, matter was turned and subdued by spirit towards abstraction: when the earthly quality - in Baroque - which the Renaissance brought into art and Reformation into religion, was once again overcome by Catholicism; then the material calm of ancient forms (columns and beams) was revitalized by imagined and life-imbuing movements.

Our architecture belongs to both major families. Both have divided us with about the same temporal share; the first six hundred years in which - and this is important - the beginnings of our culture were laid, and the national consciousness began to emerge, were attributed to the influence of the northern Christian group; the southern spirit - and of course already in a state of Renaissance revival - only came as the second current and occupies the entirety of the second half of our history from four centuries to the present; that it developed here in breadth and depth primarily through Baroque, thus its period, which is again dominated by abstraction, is characteristic for the establishment of our national spiritual essence. In fact, the predominant part in the temporal sum of our architectural history consists of the effort to escape beyond and above the limits of matter, i.e., in Gothic and Baroque; a smaller part, actually only about two centuries (the 16th and 19th), remained spiritually with a positive, receptive relationship to matter and material form.

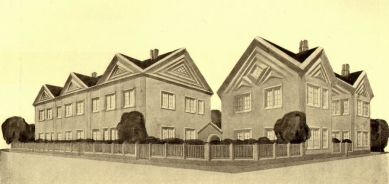

Contemporary new, so-called modern architecture still belongs by its nature and spirit to this materialistic view of art. It clearly stems from the preceding neo-Renaissance period, and all theoretical attempts to prove its connection with the empire as well as the character of its construction system (according to layman's jokes "Assyrian" or "Egyptian") are evidence that it belongs to the southern viewpoint group. This must be especially recognized; for the ideas that introduced it and which it itself brought, such as "the rebirth of art, the purification from falsely repeated historical forms, a return to modern life," etc., seemingly represent some sort of break in history towards a new, unprecedented direction. If we consider these established principles of the new architecture, its ideological affiliation will emerge more clearly and undoubtedly. Its broadest principle: the return to contemporary life (analogous to the return to nature) signifies - one cannot deny this - mere positivity and earthly quality, even if temporarily recognized as beautiful; the cleansing from old historical stylistic forms and traditions that the new architecture has resolved to undertake and has rigorously executed, while alongside its healthiness and effectiveness against the savage pseudo-historical architecture, also carries a characteristic that cannot be overlooked: a fundamental aversion to every super-material, spiritual form; also the word about the necessary functionality and materiality of architecture, which the new architecture has adopted as a corrective in its path ("what is not functional cannot be beautiful"), is a very safe but materialistic advice. Conversely, alongside these recommended bonds with earthly life, with the necessity to serve its material needs and with the recognition of matter, the new architecture has engaged little, almost nothing, in how and what it wants to artistically further abstract from these worldly assumptions. All these markings indicate the class to which the spirit of modern architecture belongs.

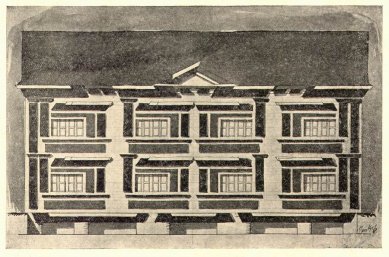

Works of new architecture realized in this spirit signify a certain return to realistic construction, to natural usage of materials and building materials; they have, after a certain logical development, rediscovered and recognized natural structural units in a bare system of prisms, and all building elements, pillars, slabs, have been returned to the material substances from which they were equipped, i.e., to the prisms of stones, beams, etc. For everything that deviates from the prismatic skeleton in any way, it can be said that through this purifying negative artistic activity, sensitivity and meaning have been lost; alongside these natural building forms, architecture has returned to a primal system of building materials stacked upon each other according to a simple technical and natural law of load-bearing support; externally, this architecture is characterized by a division into elements purely horizontal and vertical, occasionally planar, yet consistently with the exclusion of any other (such as slanted) shape possibilities: should there still be a need for plastic gradation anywhere, it is again achieved through prismatic gradation of the material.*

One can say that under the given assumptions, this current architecture has achieved a certain easy system of expression, which no longer has unresolved questions for itself. However, our feeling, which always precedes future artistic acts, inadvertently attaches attributes and sayings to the characterization of this system, which already prove the difference of our internal emotional perspective and suggest that if we notice certain negative properties in it, we feel the need for architecture to be affirmative precisely at those points. Therefore, if we consider contemporary architecture - as it has now matured - to be materialistic, less genuinely poetic, and materially flat, it signifies that there are the same internal values that have already been positively developed in the time, that they are advocating expression, and that we are missing them in architecture. This change of feeling can also be observed in the subjects that our love has chosen in the history of architecture: if in accordance with prismatic architecture, sympathetic to it until recently were historically sympathetic architectures of kindred periods, such as Greece, primitive Italianism, the Renaissance, we are beginning to engage with Gothic and Baroque, which previously felt distant to us; we see them now in the true sense, while before it seemed as if they did not exist for us. They capture our attention with the liveliness of spirit with which matter is permeated in them, and then the dramatic character of the expressive means with which their shapes are created; both, what astonishes us here, has evidently by now become a new substantial component for which our feeling has been expanded: at the same time, we find that the prismatic system and its means are no longer sufficient for full expression and appear poor to us: it seems that these judgments on the materialistic system again advocate - spirit and the will to abstraction, for which we have always had so much foundation and meaning in the north.

In this reflection, where the artistic form of matter and artistic creation is considered affirmative, we must be interested in and must reveal its opposite: the natural building form of matter and natural creation, if it exists or can be thought of as constructed.

One can say that the primary property and force corresponding to matter in the lifeless realm of nature, assuming it is itself beyond all movements of the universe, atmosphere, and earth's surface, is weight. Weight is the force tending to equalize all matter - if it were not for friction - into a great calming horizontal surface, and in further progress then into horizontal layers placed upon one another as time would bring: the purest form of performance of weight is the surface of water, sediments compressed into layers; these horizontal layered forms possess a vertical direction of weight (the path of freely falling bodies) and together create an essential shape pair of natural matter; nature expends itself in them as long as there are no other mixing properties and forces of matter and life here. If another weight (for example, the weight of upper layers) were to act upon the matter so arranged according to the law of weight, and if the matter did not resist with its cohesion, etc., a layer of matter would break off at the fracture surface perpendicular to its surface; such pure breaks indeed occur in nature under satisfactorily simplified circumstances, and the result can be regarded as naturally formed matter - matter delineated in vertical and horizontal surfaces.

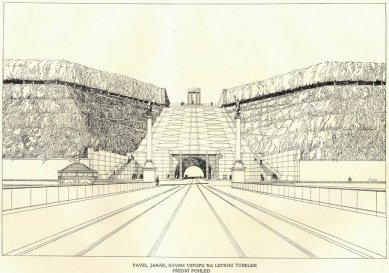

All other shapes that occur in lifeless nature, which are geometrically more complex, arise through the cooperation of a third force: the slanted fall of rain is caused by the incoming component of wind; likewise, snowdrifts, furrows, cliffs, caves, cavities, and volcanoes are all forms positively or negatively shaped from lifeless matter by another force penetrating into it, which deforms the matter and deviates it from the natural shape in which it was deposited. The most beautiful case is crystallization: here the mixing force (the crystallization force) is so immensely stronger compared to weight that - one can almost say - weight has no effect on crystallization at all; the crystallization force appears to be a weight of matter concentrated inside the matter so vehemently that it realizes itself under any circumstances in a concentrated world for itself. All these shapes have as their main characteristic, in contrast to natural primal forms (constantly limited by the system of perpendicular double surfaces), the characteristic of slanted surfaces, inclined towards the basic natural surfaces: inclination is then an equilibrium shape, arising and remaining from an imbalance by the breaking of equilibrium. Therefore, if the vertical and horizontal double surface is the shape of calm and solitary equilibrium of matter, dramatic processes and more complex bundles of forces preceded the slantingly shaped forms.

A view of the plane surface, the surface of the sea, or the vertical walls of rocks evokes - artistically - ideas of zero, dead calm and permanence, whereas slanted formations in nature, cliffs, ruins, abysses, volcanoes evoke feelings dramatic, directionally moved, sharpened and pointed; the natures of both groups of feelings are actually only proportional and coordinate to the processes that preceded them and created them. By this relationship between the natural primal shape of calm and the dramatized shape, the means by which matter is artistically conquered are given; for artistic intentions, although concerning more complex psychological compositions, fundamentally are the same as the force mixing into natural matter and its natural formation. This ultimately leads to this conclusion about the means of artistic creation: if dead matter is to be artistically transcended, i.e., enlivened, so that something may happen in it, it occurs through the system of the third surface, which approaches the natural double surface.

Here is a beautiful parallel between the means of human action and the means of artistic creation: wedges, arrows, stakes, knives, levers that physically overcome matter are all slanted surfaces.

The cause of the first human constructions and shelters was the intention of man to resist certain natural forces, rain, snow, the sun, generally incoming from above; this activity directed vertically upwards from the earth’s surface is therefore opposite to the action of weight, and it is truly the only task of this initial building system to solve the question of weight in matter and to overcome it; so that matter is not brought into a fall by weight, it is necessary to set against it a bearing surface, a material support - thus a form that again exhibits a disciplined natural system of perpendicular double surfaces. Building material most practically fits this machine-like assumption - if it is formed according to the principle of perpendicular double surfaces - into building prisms; it often presents itself in nature already in these useful shapes (bearer cubic stone, slabs of stone) or is adjusted through carving, molding (bricks). Through the natural addition and arrangement of these prismatic building units in walls, pillars, ceilings arises necessarily the entirety of the construction, unless there are other than practical intentions, again as a form created according to the prismatic system: certain resolutions of mutual relationships may be applied here, certain spatial and layout ideas; in general, however, enclosing matter in prisms is receiving its materiality.* The geometric shape of the prism for matter then arose from usefulness, from technique, not from conceptual, artistic, and philosophical conclusions.

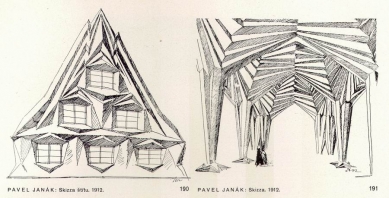

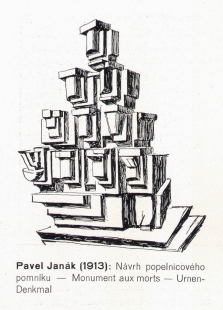

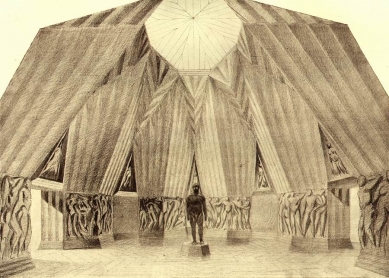

As soon as the contemplation of the essence of matter is added to this purely technical material and construction, concerning whether it is necessary, how and where it is perceived emotionally to bear forces and pressures, it signifies that the materiality of matter is no longer acknowledged so exclusively, that there are doubts and emotional opinions about matter, which once they become active change into a force penetrating beneath the prismatic surface of matter or altering it everywhere it seems unsatisfactory. The contemplating and feeling spirit mostly longs for the revitalization or clarification of matter according to its ideas, colliding with the dead materiality of matter as an invading force and reconciling with it by sculpting corners, edges, penetrating into the depth of matter wherever it does not acknowledge and does not feel with it; these changes, which artistic feeling attaches to it, are of unnatural origin, thus not derived from the double-surface system (then they would merely be corrections in the dimensions of the building prism reducing its length, width, etc.), but rather repair and change matter in the sense of dramatization primarily with the help of a third element, slanted surface. The body that can be formed from these dramatically arranged slanted surfaces is a pyramid, which is the supreme form of spiritually abstracted matter, derived from the mother natural prism. For if we think of a lying prism unburdened by anything and inscribed within it a pyramid above its base, the pyramid is a philosophical substitute for the tetrahedron: it reaches the same height with the same base, has all three of its main dimensions, but is less material because it has no unnecessary mass, and is more concentrated in the sense of height.

Architecture, as opposed to natural building, is a higher activity; it combines in itself - in general - two activities: fulfilling human purpose and artistic expression, i.e., the abstraction of matter. Therefore, its entirety unites in itself both systems of creation: technical prismatic double-surface building and abstract transformation of matter through three-surface systems, whether slanted or curvilinear. Depending on which of the two stimuli of architecture predominates, its overall character is also formed.

Primary building, regardless of which and from which time, has almost no slanted elements and is very closely related in shape - despite geographical, temporal, and national distances. From natural building arises the entire southern group of European architecture: Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, Egypt, island cultures, Greece, etc. which created the fundamental shaping language for all their later renaissances; because in this stylistic group abstract endeavors already apply, and especially the very composition of matter in relation to each other is a primary activity refined or even idealized, it can be described as the naturalism of beautiful seeing of nature.

In the peak type - in Greek architecture - there is already a series of building elements abstractly transformed: bases and capitals of columns, the step profile of the architrave, cornices, consoles, etc., are all already bent away from the vertical foundation of walls and columns, so the bounding tangential surfaces of their profiles form slanted angles with the faces of the construction; a column changes from its original pillar shape and cylindrical form into a more abstract, felt shape conical (in the Doric style).

* The materiality of the south is manifested not only in shape, but also in its other values. Greatness, for example, was realized and represented by the physical grandeur of artistic forms: colossi, etc., in Egypt, a preference for building with stones of the largest dimensions, the enlargement of the scale of the temple, when it involved a more significant temple, etc. even double-conical (entasis). Overall, however, here the abstraction was mostly limited only to transitional joint members inserted everywhere the main mechanical prismatic masses came into contact and rested upon each other: the general contour composition of construction remains within the limits of calm prismatic systems.

The old Romans, as is known, adopted the stylistic language of Greece and Asia Minor, without changing much about the relationship of both systems; late imperial Rome, however, especially exhibits a dramatic expression of basic masses in the architecture of imperial villas (folding, even bending of facades), thus rightly called Roman Baroque.

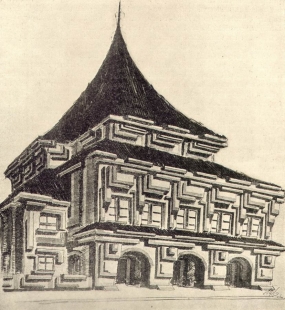

Baroque post-Renaissance Italian and especially northern signifies in the group of southern architecture another deviation from the natural to the abstract. The acquired foundation of ancient forms and systems, their calm materiality and immobility are not concordant with the spiritual life of the Baroque centuries, and the way they were transformed well illuminates the path to abstraction. Baroque, as is well known, added and imposed, heightened the expression of all forms by further addition and piling up of material: the bases and capitals of columns, beams and cornices are more sharply profiled and more inclined both in individual elements and in the whole; slabs of architraves and cornices are slanted, and conically narrowing pilasters, consoles, and pillars also appear. Alongside this means of heightening the expression on the original shape, Baroque discovered another logically progressively increasing means to abstraction: the turning and moving of entire shapes from their original calm ancient position to slants and dramatic positions against the core of the construction: columns and pillars in portals and towers in the fronts of churches are placed slanted diagonally, as if the mass of the construction had come to life and flowed out or withdrawn, moving the formerly flat composition of architecture. It is fundamentally the most abstract idea and possibility, to allow a living, shaping force to once again remodel the entire façade by pushes and pressures outwards and inwards from the foundation of the construction.*

If Baroque abstraction lies in the intensification and enlivening of matter and in the movement of matter, the principle of the northern group of architecture is the opposite: it overcomes the calm and materiality of matter by delving into it, taking away matter in the direction of the third slanted surface.

The manner of this penetrating into matter is best noticeable in the development of the pillar in the nave of the cathedral system. This pillar at the beginning is wholly quadrangular, primary; gradually its edges become more and more beveled, its character grows increasingly in both directions linking onto it arches and ribs, until in the peak of Gothic it is a quadrangular pillar, standing diagonally, ideally and abstractly replacing the original unnecessarily massive four-sided pillar. All other originally prismatic building elements undergo the same transformation: ribs, vaults, flying buttresses, etc. Portals with their slanted sides are, in the same principle, artistically deepened openings into the mass of the façade; if their sides were directly perpendicular according to the double-surface system into the depth of the wall, it would mean dismantling, cutting away all matter at this place, whereas slanted sides artistically preserve the mass of the wall. Gothic clearly recognized and mastered the artistic means of abstraction to the last consequences: the spires with which its buildings end in pinnacles, ridges of roofs, and tips of towers, are correct abstract limitations of the construction. There are beautiful explanations for this: if the tower ended in a prism, this could grow upwards indefinitely; however, if we replace it with an equally high spire, the ending is realized and undeniable; otherwise: the spire is a plastic elevation and solution of the upper surface of the prismatic tower, as if it had been lifted from it. The mass of the spire ends at a point, without the possibility of further continuation.

The East, starting already with Egypt, has had a region of gradually and unidirectionally grown cultures; the spiritual conditions long accumulated and counted thus arrived there to even more spiritually intricate abstractions of matter in architecture. Egypt in pyramids and temple constructions has, including in its walls and pylons etc., decidedly slanted abstract elements; India has architecture of abstractly tiered, repeated, and accumulated plasticity, beneath which its own building essence disappears, and architecture becomes a kind of sculpture. China and Siam on their buildings, which seem strange to us, often violate even the last natural double-surface form of their building structure; the pagodas of Siam are sort of stalactite groups of shapes, and the roofs of temples and palaces in China bend and lift at points on arched and wavy beams. It is architecture at the greatest distances from natural building and already becomes its second possibility: a plastic architectural expression.

Our architecture belongs to both major families. Both have divided us with about the same temporal share; the first six hundred years in which - and this is important - the beginnings of our culture were laid, and the national consciousness began to emerge, were attributed to the influence of the northern Christian group; the southern spirit - and of course already in a state of Renaissance revival - only came as the second current and occupies the entirety of the second half of our history from four centuries to the present; that it developed here in breadth and depth primarily through Baroque, thus its period, which is again dominated by abstraction, is characteristic for the establishment of our national spiritual essence. In fact, the predominant part in the temporal sum of our architectural history consists of the effort to escape beyond and above the limits of matter, i.e., in Gothic and Baroque; a smaller part, actually only about two centuries (the 16th and 19th), remained spiritually with a positive, receptive relationship to matter and material form.

Contemporary new, so-called modern architecture still belongs by its nature and spirit to this materialistic view of art. It clearly stems from the preceding neo-Renaissance period, and all theoretical attempts to prove its connection with the empire as well as the character of its construction system (according to layman's jokes "Assyrian" or "Egyptian") are evidence that it belongs to the southern viewpoint group. This must be especially recognized; for the ideas that introduced it and which it itself brought, such as "the rebirth of art, the purification from falsely repeated historical forms, a return to modern life," etc., seemingly represent some sort of break in history towards a new, unprecedented direction. If we consider these established principles of the new architecture, its ideological affiliation will emerge more clearly and undoubtedly. Its broadest principle: the return to contemporary life (analogous to the return to nature) signifies - one cannot deny this - mere positivity and earthly quality, even if temporarily recognized as beautiful; the cleansing from old historical stylistic forms and traditions that the new architecture has resolved to undertake and has rigorously executed, while alongside its healthiness and effectiveness against the savage pseudo-historical architecture, also carries a characteristic that cannot be overlooked: a fundamental aversion to every super-material, spiritual form; also the word about the necessary functionality and materiality of architecture, which the new architecture has adopted as a corrective in its path ("what is not functional cannot be beautiful"), is a very safe but materialistic advice. Conversely, alongside these recommended bonds with earthly life, with the necessity to serve its material needs and with the recognition of matter, the new architecture has engaged little, almost nothing, in how and what it wants to artistically further abstract from these worldly assumptions. All these markings indicate the class to which the spirit of modern architecture belongs.

Works of new architecture realized in this spirit signify a certain return to realistic construction, to natural usage of materials and building materials; they have, after a certain logical development, rediscovered and recognized natural structural units in a bare system of prisms, and all building elements, pillars, slabs, have been returned to the material substances from which they were equipped, i.e., to the prisms of stones, beams, etc. For everything that deviates from the prismatic skeleton in any way, it can be said that through this purifying negative artistic activity, sensitivity and meaning have been lost; alongside these natural building forms, architecture has returned to a primal system of building materials stacked upon each other according to a simple technical and natural law of load-bearing support; externally, this architecture is characterized by a division into elements purely horizontal and vertical, occasionally planar, yet consistently with the exclusion of any other (such as slanted) shape possibilities: should there still be a need for plastic gradation anywhere, it is again achieved through prismatic gradation of the material.*

One can say that under the given assumptions, this current architecture has achieved a certain easy system of expression, which no longer has unresolved questions for itself. However, our feeling, which always precedes future artistic acts, inadvertently attaches attributes and sayings to the characterization of this system, which already prove the difference of our internal emotional perspective and suggest that if we notice certain negative properties in it, we feel the need for architecture to be affirmative precisely at those points. Therefore, if we consider contemporary architecture - as it has now matured - to be materialistic, less genuinely poetic, and materially flat, it signifies that there are the same internal values that have already been positively developed in the time, that they are advocating expression, and that we are missing them in architecture. This change of feeling can also be observed in the subjects that our love has chosen in the history of architecture: if in accordance with prismatic architecture, sympathetic to it until recently were historically sympathetic architectures of kindred periods, such as Greece, primitive Italianism, the Renaissance, we are beginning to engage with Gothic and Baroque, which previously felt distant to us; we see them now in the true sense, while before it seemed as if they did not exist for us. They capture our attention with the liveliness of spirit with which matter is permeated in them, and then the dramatic character of the expressive means with which their shapes are created; both, what astonishes us here, has evidently by now become a new substantial component for which our feeling has been expanded: at the same time, we find that the prismatic system and its means are no longer sufficient for full expression and appear poor to us: it seems that these judgments on the materialistic system again advocate - spirit and the will to abstraction, for which we have always had so much foundation and meaning in the north.

In this reflection, where the artistic form of matter and artistic creation is considered affirmative, we must be interested in and must reveal its opposite: the natural building form of matter and natural creation, if it exists or can be thought of as constructed.

One can say that the primary property and force corresponding to matter in the lifeless realm of nature, assuming it is itself beyond all movements of the universe, atmosphere, and earth's surface, is weight. Weight is the force tending to equalize all matter - if it were not for friction - into a great calming horizontal surface, and in further progress then into horizontal layers placed upon one another as time would bring: the purest form of performance of weight is the surface of water, sediments compressed into layers; these horizontal layered forms possess a vertical direction of weight (the path of freely falling bodies) and together create an essential shape pair of natural matter; nature expends itself in them as long as there are no other mixing properties and forces of matter and life here. If another weight (for example, the weight of upper layers) were to act upon the matter so arranged according to the law of weight, and if the matter did not resist with its cohesion, etc., a layer of matter would break off at the fracture surface perpendicular to its surface; such pure breaks indeed occur in nature under satisfactorily simplified circumstances, and the result can be regarded as naturally formed matter - matter delineated in vertical and horizontal surfaces.

All other shapes that occur in lifeless nature, which are geometrically more complex, arise through the cooperation of a third force: the slanted fall of rain is caused by the incoming component of wind; likewise, snowdrifts, furrows, cliffs, caves, cavities, and volcanoes are all forms positively or negatively shaped from lifeless matter by another force penetrating into it, which deforms the matter and deviates it from the natural shape in which it was deposited. The most beautiful case is crystallization: here the mixing force (the crystallization force) is so immensely stronger compared to weight that - one can almost say - weight has no effect on crystallization at all; the crystallization force appears to be a weight of matter concentrated inside the matter so vehemently that it realizes itself under any circumstances in a concentrated world for itself. All these shapes have as their main characteristic, in contrast to natural primal forms (constantly limited by the system of perpendicular double surfaces), the characteristic of slanted surfaces, inclined towards the basic natural surfaces: inclination is then an equilibrium shape, arising and remaining from an imbalance by the breaking of equilibrium. Therefore, if the vertical and horizontal double surface is the shape of calm and solitary equilibrium of matter, dramatic processes and more complex bundles of forces preceded the slantingly shaped forms.

A view of the plane surface, the surface of the sea, or the vertical walls of rocks evokes - artistically - ideas of zero, dead calm and permanence, whereas slanted formations in nature, cliffs, ruins, abysses, volcanoes evoke feelings dramatic, directionally moved, sharpened and pointed; the natures of both groups of feelings are actually only proportional and coordinate to the processes that preceded them and created them. By this relationship between the natural primal shape of calm and the dramatized shape, the means by which matter is artistically conquered are given; for artistic intentions, although concerning more complex psychological compositions, fundamentally are the same as the force mixing into natural matter and its natural formation. This ultimately leads to this conclusion about the means of artistic creation: if dead matter is to be artistically transcended, i.e., enlivened, so that something may happen in it, it occurs through the system of the third surface, which approaches the natural double surface.

Here is a beautiful parallel between the means of human action and the means of artistic creation: wedges, arrows, stakes, knives, levers that physically overcome matter are all slanted surfaces.

The cause of the first human constructions and shelters was the intention of man to resist certain natural forces, rain, snow, the sun, generally incoming from above; this activity directed vertically upwards from the earth’s surface is therefore opposite to the action of weight, and it is truly the only task of this initial building system to solve the question of weight in matter and to overcome it; so that matter is not brought into a fall by weight, it is necessary to set against it a bearing surface, a material support - thus a form that again exhibits a disciplined natural system of perpendicular double surfaces. Building material most practically fits this machine-like assumption - if it is formed according to the principle of perpendicular double surfaces - into building prisms; it often presents itself in nature already in these useful shapes (bearer cubic stone, slabs of stone) or is adjusted through carving, molding (bricks). Through the natural addition and arrangement of these prismatic building units in walls, pillars, ceilings arises necessarily the entirety of the construction, unless there are other than practical intentions, again as a form created according to the prismatic system: certain resolutions of mutual relationships may be applied here, certain spatial and layout ideas; in general, however, enclosing matter in prisms is receiving its materiality.* The geometric shape of the prism for matter then arose from usefulness, from technique, not from conceptual, artistic, and philosophical conclusions.

As soon as the contemplation of the essence of matter is added to this purely technical material and construction, concerning whether it is necessary, how and where it is perceived emotionally to bear forces and pressures, it signifies that the materiality of matter is no longer acknowledged so exclusively, that there are doubts and emotional opinions about matter, which once they become active change into a force penetrating beneath the prismatic surface of matter or altering it everywhere it seems unsatisfactory. The contemplating and feeling spirit mostly longs for the revitalization or clarification of matter according to its ideas, colliding with the dead materiality of matter as an invading force and reconciling with it by sculpting corners, edges, penetrating into the depth of matter wherever it does not acknowledge and does not feel with it; these changes, which artistic feeling attaches to it, are of unnatural origin, thus not derived from the double-surface system (then they would merely be corrections in the dimensions of the building prism reducing its length, width, etc.), but rather repair and change matter in the sense of dramatization primarily with the help of a third element, slanted surface. The body that can be formed from these dramatically arranged slanted surfaces is a pyramid, which is the supreme form of spiritually abstracted matter, derived from the mother natural prism. For if we think of a lying prism unburdened by anything and inscribed within it a pyramid above its base, the pyramid is a philosophical substitute for the tetrahedron: it reaches the same height with the same base, has all three of its main dimensions, but is less material because it has no unnecessary mass, and is more concentrated in the sense of height.

Architecture, as opposed to natural building, is a higher activity; it combines in itself - in general - two activities: fulfilling human purpose and artistic expression, i.e., the abstraction of matter. Therefore, its entirety unites in itself both systems of creation: technical prismatic double-surface building and abstract transformation of matter through three-surface systems, whether slanted or curvilinear. Depending on which of the two stimuli of architecture predominates, its overall character is also formed.

Primary building, regardless of which and from which time, has almost no slanted elements and is very closely related in shape - despite geographical, temporal, and national distances. From natural building arises the entire southern group of European architecture: Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, Egypt, island cultures, Greece, etc. which created the fundamental shaping language for all their later renaissances; because in this stylistic group abstract endeavors already apply, and especially the very composition of matter in relation to each other is a primary activity refined or even idealized, it can be described as the naturalism of beautiful seeing of nature.

In the peak type - in Greek architecture - there is already a series of building elements abstractly transformed: bases and capitals of columns, the step profile of the architrave, cornices, consoles, etc., are all already bent away from the vertical foundation of walls and columns, so the bounding tangential surfaces of their profiles form slanted angles with the faces of the construction; a column changes from its original pillar shape and cylindrical form into a more abstract, felt shape conical (in the Doric style).

* The materiality of the south is manifested not only in shape, but also in its other values. Greatness, for example, was realized and represented by the physical grandeur of artistic forms: colossi, etc., in Egypt, a preference for building with stones of the largest dimensions, the enlargement of the scale of the temple, when it involved a more significant temple, etc. even double-conical (entasis). Overall, however, here the abstraction was mostly limited only to transitional joint members inserted everywhere the main mechanical prismatic masses came into contact and rested upon each other: the general contour composition of construction remains within the limits of calm prismatic systems.

The old Romans, as is known, adopted the stylistic language of Greece and Asia Minor, without changing much about the relationship of both systems; late imperial Rome, however, especially exhibits a dramatic expression of basic masses in the architecture of imperial villas (folding, even bending of facades), thus rightly called Roman Baroque.

Baroque post-Renaissance Italian and especially northern signifies in the group of southern architecture another deviation from the natural to the abstract. The acquired foundation of ancient forms and systems, their calm materiality and immobility are not concordant with the spiritual life of the Baroque centuries, and the way they were transformed well illuminates the path to abstraction. Baroque, as is well known, added and imposed, heightened the expression of all forms by further addition and piling up of material: the bases and capitals of columns, beams and cornices are more sharply profiled and more inclined both in individual elements and in the whole; slabs of architraves and cornices are slanted, and conically narrowing pilasters, consoles, and pillars also appear. Alongside this means of heightening the expression on the original shape, Baroque discovered another logically progressively increasing means to abstraction: the turning and moving of entire shapes from their original calm ancient position to slants and dramatic positions against the core of the construction: columns and pillars in portals and towers in the fronts of churches are placed slanted diagonally, as if the mass of the construction had come to life and flowed out or withdrawn, moving the formerly flat composition of architecture. It is fundamentally the most abstract idea and possibility, to allow a living, shaping force to once again remodel the entire façade by pushes and pressures outwards and inwards from the foundation of the construction.*

If Baroque abstraction lies in the intensification and enlivening of matter and in the movement of matter, the principle of the northern group of architecture is the opposite: it overcomes the calm and materiality of matter by delving into it, taking away matter in the direction of the third slanted surface.

The manner of this penetrating into matter is best noticeable in the development of the pillar in the nave of the cathedral system. This pillar at the beginning is wholly quadrangular, primary; gradually its edges become more and more beveled, its character grows increasingly in both directions linking onto it arches and ribs, until in the peak of Gothic it is a quadrangular pillar, standing diagonally, ideally and abstractly replacing the original unnecessarily massive four-sided pillar. All other originally prismatic building elements undergo the same transformation: ribs, vaults, flying buttresses, etc. Portals with their slanted sides are, in the same principle, artistically deepened openings into the mass of the façade; if their sides were directly perpendicular according to the double-surface system into the depth of the wall, it would mean dismantling, cutting away all matter at this place, whereas slanted sides artistically preserve the mass of the wall. Gothic clearly recognized and mastered the artistic means of abstraction to the last consequences: the spires with which its buildings end in pinnacles, ridges of roofs, and tips of towers, are correct abstract limitations of the construction. There are beautiful explanations for this: if the tower ended in a prism, this could grow upwards indefinitely; however, if we replace it with an equally high spire, the ending is realized and undeniable; otherwise: the spire is a plastic elevation and solution of the upper surface of the prismatic tower, as if it had been lifted from it. The mass of the spire ends at a point, without the possibility of further continuation.

The East, starting already with Egypt, has had a region of gradually and unidirectionally grown cultures; the spiritual conditions long accumulated and counted thus arrived there to even more spiritually intricate abstractions of matter in architecture. Egypt in pyramids and temple constructions has, including in its walls and pylons etc., decidedly slanted abstract elements; India has architecture of abstractly tiered, repeated, and accumulated plasticity, beneath which its own building essence disappears, and architecture becomes a kind of sculpture. China and Siam on their buildings, which seem strange to us, often violate even the last natural double-surface form of their building structure; the pagodas of Siam are sort of stalactite groups of shapes, and the roofs of temples and palaces in China bend and lift at points on arched and wavy beams. It is architecture at the greatest distances from natural building and already becomes its second possibility: a plastic architectural expression.

Art Magazine I, 1911/12, pp. 162-170

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

krásný text o jižním materialismu

Vích

31.10.08 09:12

show all comments