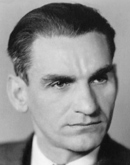

Josef Polášek

*27. 3. 1899 – Boršov u Kyjova, Czech Republic

†20. 12. 1946 – Brno, Czech Republic

Biography

After graduating from the Prague School of Applied Arts under Professor Pavel Janák, during which he published several designs mainly in the magazine Styl and participated in a competition for the extension of the Tyrš House in Prague, Polášek moved to Brno in 1924, where he found a job in the construction department of the municipal office. There he initially assisted (the ceremonial hall of the Brno municipal cemetery, 1925) and later collaborated with Bohuslav Fuchs.The first independent project by Polášek became the rarely used type of single-story family house No. 805 (1929-30) in Kyjov, in which the architect could apply the knowledge gained from a recent study trip to the Netherlands, financed in 1928 by a travel scholarship from the School of Applied Arts. The book Dutch Architecture (1931) later summarized his impressions.

When Polášek died prematurely in December 1946 from incurable tuberculosis, his work was essentially confined to a single decade dominated by functionalism in the thirties. A period that, compared to most of his collaborators and contemporaries in Brno, was incredibly short.

Kateřina Lopatová

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

Realizations and projects

Other Works

Family Houses, Kyjov and Břeclav, 1929School, Dobročkovice, 1930

Set of Rental Houses, Brno-Husovice, 1930–1931

School Expansion, Brno-Veveří, 1931

Masaryk Colony of Houses for Financial Officials, Košice, 1930–1932

Administrative Building of the First Czech Glassworks, Kyjov, 1930–1934

School, Brno-Obřany, 1931

Sokol Gym and Community Hall, Brno-Královo Pole (with K. Láník), 1932

Rental House, Brno-Černá Pole, 1932

Family Houses, Kyjov, Vyškov, Přerov, and Nový Smokovec, 1932

Rental House, Česká Třebová, 1932–1934

Family House, Kroměříž, 1934

Savings Bank, Velké Meziříčí, (with E. Žáček), 1934–1935

Renovations of the New Town Hall, Brno, 1935

Moravian Bank, Boskovice, 1935

Family House, Kyjov, 1935

Rental House, Brno-Masarykova Quarter, 1936–1937

Family House, Kyjov, 1937

Moravian Bank, Kolín, 1938

Rental Houses, Brno-Husovice and Brno-Staré Brno, 1938

Rental Houses for the Poor, Brno-Zábrdovice, (with V. Kuba), 1937–1938

Moravian Bank, Nymburk, 1938

Family House, Kyjov, 1938

Schools, Brno-Tuřany, Brno-Staré Brno, and Brno-Kohoutovice, 1938–1939

Rental House, Česká Třebová, 1939

Family Houses, Kyjov and Brno-Žabovřesky, 1939

Family Houses, Kyjov, Slavkov u Brna, Brno-Ivanovice, and Brno-Jundrov, 1939–1940

Rental House, Hranice, 1941

Renovation of the Town Hall and Museum, Velké Meziříčí, 1942

Interior Renovation of the Castle, Hranice (with O. Oplatek), 1943

Later realized schools, Kyjov, Mistřín, and Boršov, 1946

Rental Houses, Brno-Královo Pole (with J. Bureš, J. Kroh and V. Kuba), 1946–1948

SHORT SEARCH FOR A HARMONIOUS CENTER

The prerequisites for the strong position of interwar Brno architecture, as we undoubtedly perceive it in the context of that period today, were created both by the active role of city and regional building authorities and the frequency of talented architects who had the opportunity to design here. Or rather, the interdependence of both mentioned facts, and certainly not only them. In a stimulating environment, nourished by the distribution of contracts among a number of competitors and friends, Bohuslav Fuchs, Jindřich Kumpošt, Mojmír Kyselka, Jan Víšek, and Jaroslav Grunt worked side by side, each contributing to the rapid developments. Within the span of architectural production defined by contemporary styles, they represented perhaps the "most austere" position—both in terms of form and choice of tasks—realizing another of them. Unlike many colleagues, he did not focus on projects for corporate offices, hotels, or representative family villas, although he did not completely close himself off from such tasks, as we shall see, the essential part of his work became rental houses with small apartments, houses for the poor, and school buildings. This year marks 100 years since the birth of Josef Polášek, the architect of "social" buildings."Here we build expensive public buildings on one side, block colonies on the other, and we have found, except for a few exceptions, no harmonious center that would represent the cultural state of the nation," wrote Josef Polášek together with Bohuslav Fuchs in 1929 in an article reporting on the second international congress of modern architecture CIAM in Frankfurt am Main. Shortly before this time, Polášek began his independent design activity, partly heralded by the onset of the economic crisis and the need to respond to its consequences, and on the other hand defined by the onset of war, associated with restrictions on construction activities. When Polášek prematurely died in December 1946 from incurable tuberculosis, his work was effectively confined to a single decade dominated by functionalism. This period, in contrast to most of his Brno collaborators and contemporaries, was incredibly short.

BEGINNINGS

After graduating from the Prague School of Applied Arts under Professor Pavel Janák, during which he published several designs primarily in the magazine Styl and participated in the competition for the renovation of the Tyrš House in Prague, Polášek moved to Brno in 1924, where he found employment in the city hall's construction department. Here he initially assisted (the ceremonial hall of the Brno city cemetery, 1925) and later collaborated with Bohuslav Fuchs. He himself applied in 1926 for a project for the sick fund in Kyjov, and although the realization was ultimately not awarded to him, a public poll documented in the press indicates an extraordinarily favorable attitude towards Polášek's solution. Soon after—no later than September 1927—he obtained from the local congregation of the Czech Brethren Evangelical Church the construction of a new prayer house, which is to date his first known independent realization. The project is characterized by a simple geometric layout, composed of three cuboidal bodies. The purity of architectural expression, austerity, and the absence of layers piled on the basic starting shape certainly corresponded not only to Polášek's foundation but also aligned with the principles of Protestant theology. Unlike the prayer house, where he initially concealed his authorship under the monogram JPK and only revealed his anonymity upon completion, he displayed ten projects by the end of 1927 very officially. The significance of this inconspicuous act can only be speculated upon today. It is certain that starting from 1928, he began designing family houses for builders from Kyjov surprisingly often.

The first realized was an infrequently used type of single-story family house no. 805 (1929-30), where the architect could utilize knowledge from his recent study stay in the Netherlands, funded by a travel scholarship from the School of Applied Arts in 1928. The book "Dutch Architecture" (1931), which summarized his impressions somewhat later, brought—besides photographs of buildings by architects associated with the functionalist magazine Opbouw: Duiker, Oud, Brinkman, Vlucht, or Bijvoet, which undoubtedly attracted Polášek's attention the most—also insights into contemporary structural and typological achievements, as well as interesting observations that often extended to analyses of the historical development of the cities observed or sociological connections. Although the favorable response from clients in his native Kyjov certainly supported the beginnings of Polášek's independent design, it is undisputable that the fundamental significance for strengthening the architect's position lay in the realizations and activities in Brno. Here, he participated in the work of the international organization CIAM's section, got involved with the Left Front branch, and published not only in the magazine Index. Here he also designed school buildings for Masaryk Quarter (1928-29) and Vesna on Lípa Street (1929-31), reflecting enthusiasm for the reform trends in education recently encountered in the Netherlands.

CHEAP HOUSES

The impacts of the economic recession, which heightened the divide between the 1920s and 1930s, the then government sought to somewhat mitigate by adopting a 1930 amendment to the law that supported the construction of houses with cheap apartments. A significant problem was considered by a number of architects led by Karel Teige, so it is no wonder that its solution also occupied left-leaning Polášek. As R. Švácha pointed out, three functionalist housing estates in Brno at Vranovská (1930-31) and Skácelova streets (1931-32) as well as the colony of bank officials in Košice (1930-31) must be associated with the mentioned legislative measure. The buildings, assembled according to the functionalism-promoted row scheme (Skácelova) or more closed formations, were always kept in this period with a simple cuboidal volume, whose depth was revealed by either cut-through or, conversely, suspended balconies—again in clean rectangular shapes. The formally austere to ascetic approach, working with balanced proportions and perhaps also calculating with the play of shadows cast on white façades, never fell into a cold stereotypical impression. Such a perspective is akin to the ideal of Neue Sachlichkeit, the new objectivity, as seen by German functionalism. Similar ideas guided him in designing other school buildings in Brno-Obřany (1931-33) and Slatina (around 1932).

FAMILY HOUSES

However, to present Polášek only as an author of residential blocks and schools would be incorrect and oversimplifying. He also designed a number of family houses, in which the architect's restrained attitude toward form typically prevailed over the ostentatious presentation of luxury, as in the case of his own villa in Brno (1932), a house in Vyškov (1933-34), and the two in Přerov (1931, 1933). The same perspective guided most of the family houses in the aforementioned Kyjov, where he likely built at least ten—perhaps thanks also to the active role of the city council initiating private construction. A more comfortable version of Polášek's work is primarily represented by the intricately arranged villa no. 896 from 1933-1934, whose typological relationship to the Alfa boarding house in Nový Smokovec (1932) would be further strengthened by a tubular structure—similar to that of Alfa, albeit at a smaller scale—depicted in the Kyjov project.

GRADUAL ENRICHMENT OF BUILDING EXPRESSION

In the second half of the 1930s, this corresponded with the period's renewed consideration of human psychology. Many—including Polášek—criticized the mechanized functionalist approach. In 1934, the architect did not refuse the reconstruction of the Baroque so-called New Town Hall in Brno; numerous savings bank and bank projects (Velké Meziříčí 1935, Boskovice, Kyjov 1936) were gradually re-integrated into older historical developments. Similar retreats from the militant doctrines of functionalism can be observed in the design of small apartment buildings on Brno's Dačického, Zvěřinova, Ypsilantiho streets, or on the Svitavy embankment. Once exclusively smooth façades increasingly covered with bands of structured round glass brick windows, as in the case of Brno's apartment building on Údolní Street (1937) or on the angled wall of the school in Křídlovická (1938-39); the volumes often bore saddle roofs. The elaboration of tendencies that gradually asserted themselves in Polášek's work in the second half of the 1930s, as well as the decisive abandonment of the strict orthogonality of early work, represent a summer house in Brno-Bystrci from 1937. In front of the entire facade, an elegant curve of the terrace runs.

However, a fundamental work of this period undoubtedly became the complex of buildings of the Moravian Savings Bank on Brno's Jánská Street, whose project with a concavely curved risalit was developed by Polášek in 1936-1937 together with Jindřich Blum and Otakar Oplatek (completed in 1939). The monumental scale of this building also characterizes one of the last projects—the district school in Kyjov. Just like with other post-war tasks, he collaborated with Jaroslav Bureš this time as well. However, the realization was completed only in 1953 and thus far exceeded Polášek's own lifetime. It shifted his work into years when searching was replaced by a presented goal and the "center" was displaced.

0 comments

add comment