Karel Malich Art School

Art activities in passive standard

Holice can be found on the map of Slovakia near Dunajská Streda, in Haná near Olomouc, or also east of Pardubice, and it is in this six-thousand-strong East Bohemian town where the latest piece in the architectural mosaic of the Holice cultural district is located. While many municipalities heavily draw on subsidies from the European Union without thoroughly considering future use and ensuring operation, the project for the new art school in Holice was a long-term intention that all local residents wished for and saved for since the Velvet Revolution. The fact that this was a shared goal is demonstrated by the fact that they saved for the school for over twenty years, regardless of who led the town hall. Holice has shown that it is possible to get by without subsidies. Continuity and shared goals will pay off in a quality environment.

It is no coincidence that Holice chose a proven architect for the selection, as buildings from renowned creators have been established here even before the founding of Czechoslovakia. In the northern suburbs stands a Sokol hall (1912-13) designed by Otakar Novotný, who drew inspiration for his design from his journey among Dutch modernists. Half a century later, on the opposite side of Holubova street, a cultural house (1956-61) and a museum (1965) by Slovak architect Štefan Imrich were built. Both of these buildings transcended the shadow of socialist realism from the 1950s and lean more towards a classicizing form, whose timeless monumental expression still finds its supporters today, including architect David Vávra, who approached the design of the museum Emila Holuba's interior reconstruction (2012) in his own way, but fully respected the original expression. With the start of the new school year (one hundred years since the completion of the local Sokol hall), the six-thousand-strong Holice welcomed another quality building in the sports-cultural complex lining Holubova street, where in addition to the previously mentioned Sokol hall, cultural house, and museum, there is also a primary school, kindergarten, children and youth house, sports hall, tennis courts, and football stadium. The wide range of activities reflects the long-term policy of the town, offering a full social life in a small town.

The birth of the new school project is lengthy but clear and logical, as happens when all parties pull together. On the other hand, the actual implementation had to be completed in a tight deadline of seventeen months.

The art school had long been housed in unsuitable conditions on Husova street, where the original building underwent necessary modifications, but the teaching was inadequate here. The town was lacking not only a suitable art school but also a community hall. Both situations were attempted to be addressed with a single project for which a building permit was issued in 2011, but after recalculating all the costs, the town recognized that it would not have enough funds for its operation and commissioned an optimization of the design. Thus, three proposals gathered at the city council for decision-making: a sprawling two-story proposal with energy consumption categorized as C from Milan Košař of the Pardubice-based studio Archiko and a compact passive standard proposal from Dalibor Borák of the Brno studio Dobrý dům, which came to the same amount. The third and most economical variant considered the reconstruction of the local jail, where future users would have to deal with a number of limitations again. Ultimately, the economic and sustainable operation was more acceptable to the council members. The decision was issued in the autumn of 2012, and construction began in March 2013. However, construction firms were not rushing to participate in the tender with precisely set specifications and a tight budget.

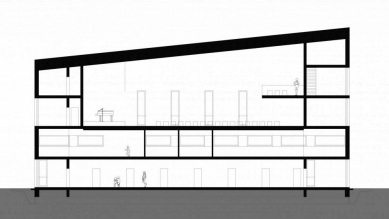

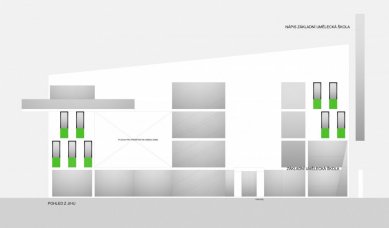

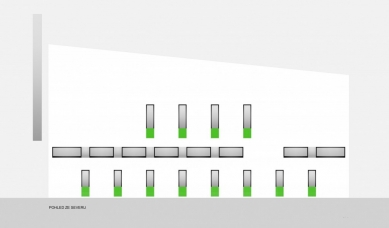

The new school is, from an urban perspective, part of the revitalization of public spaces and the completion of the northern side of the cultural space. To achieve the greatest energy savings, the building had to be as compact as possible. For the greatest sustainability of the building, materials with the lowest possible proportion of primary energy for production and transport were used. Due to the low budget, the facade surfaces remained smooth with the use of standard window openings. The internal spatial concept is dominated by a four-story foyer occupying the entire southern third of the building. Its orientation also serves as a heat-collecting collector. The generously designed spaces, through which every visitor to the school must pass, are also exhibition halls named after significant local artists, where exhibitions of works by students, teachers, and occasional other artists can take place. In addition to the communication qualities of the foyer, it serves as a space for social gatherings, dispersal areas before the halls, a café, and a lookout on the top floor.

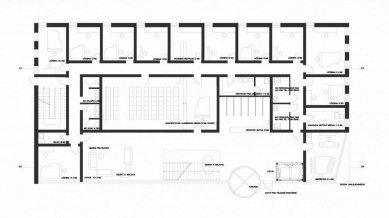

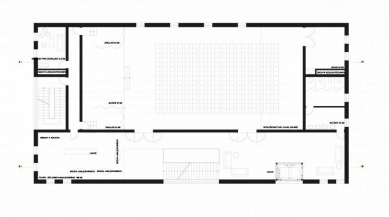

As it rises, the building "thins out." The walls decrease and the size of the rooms increases. While the ground floor consists of a series of small rehearsal rooms separated by massive walls to prevent musicians from disturbing each other, the first upper floor contains a large mirrored dance hall and studios for art and ceramics circles. On the second floor lies the largest room in the entire building—a two-story multipurpose hall,

which can host various conferences and educational programs in addition to traditional social events. On the top floor is a café with a lookout, access to the gallery, and technological support.

The slanted cut and large-scale glazing of the building's southeast corner is one of the few elements that deviate from the economical design approach. The reasoning is the fact that it showcases the most valuable asset the school has—the teaching staff. Teachers had to get used to this novelty for a while, but after a month, they no longer find it unusual to be observed by passersby as they prepare for lessons.

Although the architects had to adhere to the principles of energy-efficient construction and utilize local resources and technologies available from local companies, they had enough courage to embark on a path of experimentation. For example, the roofing of the main social hall is created from cold-bent steel beams using Borabela technology, which was applied in such an extensive scale in the Czech Republic for the very first time. By employing new methods, they managed not only to reduce already minimized costs but also the overall burden and additionally accelerated the construction process. Furthermore, the authors sought to optimize internal operations and to achieve the most natural functioning without the need for electronic involvement.

Construction methods and utilized technologies are one aspect, but since this is a public institution with a cultural focus, the artistic aspect must not be overlooked. The art school carries not only the name of artist Karel Malich but also two of his sculptures designed this year for specific locations in the building—with a black wall sculpture No. 69 above the entrance on the southern facade and a white hanging sculpture No. 64 in the interior above the staircase on the top floor. Karel Malich, who reaches a significant 90th birthday in October, personally attended the festive opening of the school. In addition to these two Malich artifacts, the information system was taken care of by the graphic studio of Aleš Najbrt.

The school currently serves six hundred students from Holice and nearby villages. Music, art, dance, and drama courses are conducted here. The school director humorously compares moving into the new building to moving up from the district league to the Champions League. That the school is the cultural center of the city is already evidenced by its hopelessly full schedule and courses taking place on weekends. We will be able to ascertain the success of the passive concept only after the first winter.

This article for the ARCH magazine 2014/11 could have emerged thanks to the willingness and insights of the client (Vítězslav Vondrouš, Deputy Mayor of Holice), user (František Machač, director of the elementary art school), and author (Dalibor Borák, Dobrý dům studio), with whom the author of the article personally met on Friday, October 10, 2014.

Holice can be found on the map of Slovakia near Dunajská Streda, in Haná near Olomouc, or also east of Pardubice, and it is in this six-thousand-strong East Bohemian town where the latest piece in the architectural mosaic of the Holice cultural district is located. While many municipalities heavily draw on subsidies from the European Union without thoroughly considering future use and ensuring operation, the project for the new art school in Holice was a long-term intention that all local residents wished for and saved for since the Velvet Revolution. The fact that this was a shared goal is demonstrated by the fact that they saved for the school for over twenty years, regardless of who led the town hall. Holice has shown that it is possible to get by without subsidies. Continuity and shared goals will pay off in a quality environment.

It is no coincidence that Holice chose a proven architect for the selection, as buildings from renowned creators have been established here even before the founding of Czechoslovakia. In the northern suburbs stands a Sokol hall (1912-13) designed by Otakar Novotný, who drew inspiration for his design from his journey among Dutch modernists. Half a century later, on the opposite side of Holubova street, a cultural house (1956-61) and a museum (1965) by Slovak architect Štefan Imrich were built. Both of these buildings transcended the shadow of socialist realism from the 1950s and lean more towards a classicizing form, whose timeless monumental expression still finds its supporters today, including architect David Vávra, who approached the design of the museum Emila Holuba's interior reconstruction (2012) in his own way, but fully respected the original expression. With the start of the new school year (one hundred years since the completion of the local Sokol hall), the six-thousand-strong Holice welcomed another quality building in the sports-cultural complex lining Holubova street, where in addition to the previously mentioned Sokol hall, cultural house, and museum, there is also a primary school, kindergarten, children and youth house, sports hall, tennis courts, and football stadium. The wide range of activities reflects the long-term policy of the town, offering a full social life in a small town.

The birth of the new school project is lengthy but clear and logical, as happens when all parties pull together. On the other hand, the actual implementation had to be completed in a tight deadline of seventeen months.

The art school had long been housed in unsuitable conditions on Husova street, where the original building underwent necessary modifications, but the teaching was inadequate here. The town was lacking not only a suitable art school but also a community hall. Both situations were attempted to be addressed with a single project for which a building permit was issued in 2011, but after recalculating all the costs, the town recognized that it would not have enough funds for its operation and commissioned an optimization of the design. Thus, three proposals gathered at the city council for decision-making: a sprawling two-story proposal with energy consumption categorized as C from Milan Košař of the Pardubice-based studio Archiko and a compact passive standard proposal from Dalibor Borák of the Brno studio Dobrý dům, which came to the same amount. The third and most economical variant considered the reconstruction of the local jail, where future users would have to deal with a number of limitations again. Ultimately, the economic and sustainable operation was more acceptable to the council members. The decision was issued in the autumn of 2012, and construction began in March 2013. However, construction firms were not rushing to participate in the tender with precisely set specifications and a tight budget.

The new school is, from an urban perspective, part of the revitalization of public spaces and the completion of the northern side of the cultural space. To achieve the greatest energy savings, the building had to be as compact as possible. For the greatest sustainability of the building, materials with the lowest possible proportion of primary energy for production and transport were used. Due to the low budget, the facade surfaces remained smooth with the use of standard window openings. The internal spatial concept is dominated by a four-story foyer occupying the entire southern third of the building. Its orientation also serves as a heat-collecting collector. The generously designed spaces, through which every visitor to the school must pass, are also exhibition halls named after significant local artists, where exhibitions of works by students, teachers, and occasional other artists can take place. In addition to the communication qualities of the foyer, it serves as a space for social gatherings, dispersal areas before the halls, a café, and a lookout on the top floor.

As it rises, the building "thins out." The walls decrease and the size of the rooms increases. While the ground floor consists of a series of small rehearsal rooms separated by massive walls to prevent musicians from disturbing each other, the first upper floor contains a large mirrored dance hall and studios for art and ceramics circles. On the second floor lies the largest room in the entire building—a two-story multipurpose hall,

which can host various conferences and educational programs in addition to traditional social events. On the top floor is a café with a lookout, access to the gallery, and technological support.

The slanted cut and large-scale glazing of the building's southeast corner is one of the few elements that deviate from the economical design approach. The reasoning is the fact that it showcases the most valuable asset the school has—the teaching staff. Teachers had to get used to this novelty for a while, but after a month, they no longer find it unusual to be observed by passersby as they prepare for lessons.

Although the architects had to adhere to the principles of energy-efficient construction and utilize local resources and technologies available from local companies, they had enough courage to embark on a path of experimentation. For example, the roofing of the main social hall is created from cold-bent steel beams using Borabela technology, which was applied in such an extensive scale in the Czech Republic for the very first time. By employing new methods, they managed not only to reduce already minimized costs but also the overall burden and additionally accelerated the construction process. Furthermore, the authors sought to optimize internal operations and to achieve the most natural functioning without the need for electronic involvement.

Construction methods and utilized technologies are one aspect, but since this is a public institution with a cultural focus, the artistic aspect must not be overlooked. The art school carries not only the name of artist Karel Malich but also two of his sculptures designed this year for specific locations in the building—with a black wall sculpture No. 69 above the entrance on the southern facade and a white hanging sculpture No. 64 in the interior above the staircase on the top floor. Karel Malich, who reaches a significant 90th birthday in October, personally attended the festive opening of the school. In addition to these two Malich artifacts, the information system was taken care of by the graphic studio of Aleš Najbrt.

The school currently serves six hundred students from Holice and nearby villages. Music, art, dance, and drama courses are conducted here. The school director humorously compares moving into the new building to moving up from the district league to the Champions League. That the school is the cultural center of the city is already evidenced by its hopelessly full schedule and courses taking place on weekends. We will be able to ascertain the success of the passive concept only after the first winter.

This article for the ARCH magazine 2014/11 could have emerged thanks to the willingness and insights of the client (Vítězslav Vondrouš, Deputy Mayor of Holice), user (František Machač, director of the elementary art school), and author (Dalibor Borák, Dobrý dům studio), with whom the author of the article personally met on Friday, October 10, 2014.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment