Family house of architect Růžena Žertová

The construction of one's own house is usually a cornerstone of an architect's or architect's work. Růžena Žertová, who, according to her own words, had no interest in family homes until then, was led to the design and subsequent realization of a family house by existential problems that she encountered with her husband Igor Svoboda in 1978 after being evicted from their attic apartment on Dvořákova street in the center of Brno. At that time, the architect learned about a vacant plot of land in the Brno district of Žabovřesky. The neglected plot of 450 m² at the end of Zákoutí street had served builders of nearby row houses, designed by Zdeněk Řihák and built shortly before, for the disposal of construction waste; however, it offered the couple a real opportunity to solve the pressing issue of their own housing. The Office of the Chief Architect of the City of Brno was then faced with the necessity to clear the land, and thus, shortly afterwards, approved Žertová's and Svoboda's application for the sale of the plot.

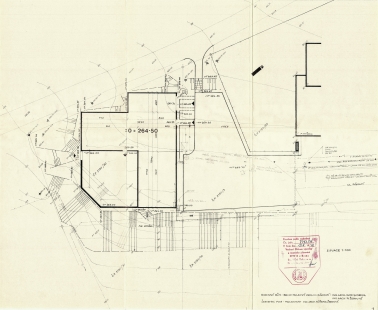

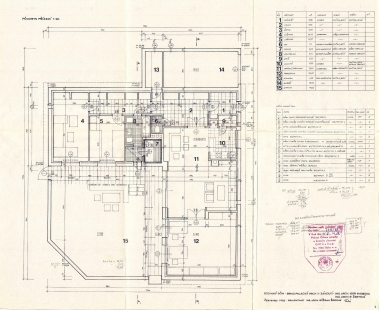

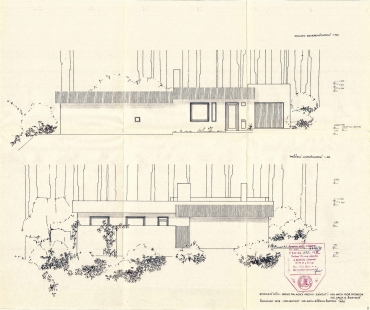

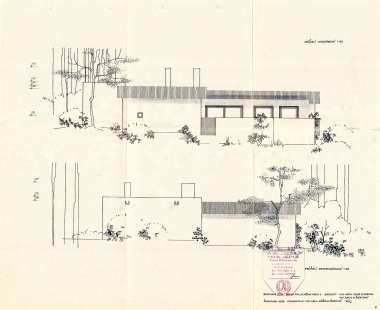

The determining premises for the design of the house, which visually concludes the development of the northwest front of the street, became the limited size of the plot, unstable subsoil, and also the assumption that the building would serve only two people. From these considerations, the concept of a single-story house based on reinforced concrete drilled piles and with an L-shaped floor plan emerged. The somewhat small plot, defined by the two wings of the house, was conceived by Žertová as an atrium. The overall layout was enclosed by a brick wall in the form of an incomplete square measuring 15 x 15 m. From the compact mass of the living areas, only the volume of the garage was allowed to protrude. In placing the house on the plot, the architect respected the orientation of the cardinal directions - the grassy atrium measuring 9 x 9 m faces south and offers views of the city, while the garage is situated on the northwest side of the plot towards the forest. Through this configuration, Žertová achieved sufficiently sunlit private spaces while simultaneously defining the building against the wooded slope.

The atrium played a key role in the spatial arrangement and layout of the house. Žertová oriented all living rooms and the bathroom towards it. The clear layout arises from the division of the house into two operating parts. In the arm facing the street bay in front of the house, Žertová placed the living area with a fireplace, kitchen, dining nook, and a study for herself and her husband. The architect reserved the second arm for the quiet part of the house - leading from the entrance hall, which is directly connected to both the garage and the adjoining storage room, is a closet with entrances to the bathroom with sauna, guest room, and bedroom.

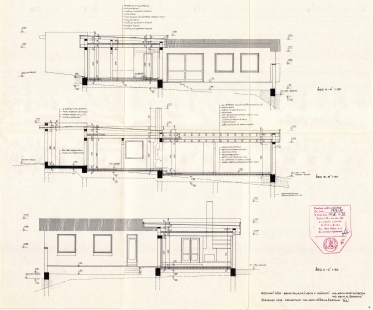

Růžena Žertová achieved balanced spatial relationships within the building primarily through the proportions of the rooms in the communal part of the house, which has a width of 5.6 m. She positioned the floor level of the living space and study - while maintaining the same clear height of 2.5 m - 30 cm lower than the other rooms of the building (in contrast, she raised the level of the garage by 20 cm). The qualities of the flowing space of this wing, whose natural counterpart is the disciplined layout of the quiet part of the house, are further enhanced by the changing light conditions throughout the day. While the kitchen area, oriented towards the street, brings in northeast light, the living space opens with a glazed wall featuring fixed frameless glazing and an opening door wing to the southwest. With light, Růžena Žertová worked sensitively in other parts of the house as well. She illuminated the entrance hall with a frameless glazed window at the height of the entire floor next to the entrance door. Twice - in the living area and in the bedroom - she utilized a window reminiscent of a loophole, serving as a jewel of firmly glazed panels, which included both clear and cast structured glass. These small openings, in both cases, bring diffused daylight into the corner of the room (the window in the bedroom also emphasizes one of the two main axes of the house and allows it to be seen completely up to the glazing at the entrance door). The author also supported the luminosity of the space with glazed doors in all living rooms. In contrast, she left the northwest facade of the house adjacent to the forest path completely without windows.

Knowing that she would realize the house by herself, Žertová thoroughly considered not only the spatial and layout arrangement but also the structural solutions of the building. She succeeded in advancing beyond the usual frameworks of socialist construction - due to better thermal insulation properties, she designed the load-bearing walls as a sandwich of aerated concrete blocks, air gaps, and solid bricks. For the same reason, she modified the standard tilt windows measuring 1.5 m x 1.5 m, which were subsequently fitted to the outer face of the walls, for double glazing, and implemented underfloor heating in part of the interior. Žertová designed the ceiling structure from ceramic inserts placed into steel beams, the flat roof, which extends 45 cm beyond the building's footprint, as a double-shell. The "face" of the roof was equipped with vertically layered dark brown wooden cladding. With the same paint - a very popular Luxol at the time - she color-coordinated the fillings of openings and the wooden grid of the narrow strip of terrace bordering the bedroom wing of the house. In part of the atrium along the residential wing, as well as on the access sidewalk and in the windbreak on the other side of the house, she laid marble tiles imported from the then Yugoslavia. She directed rainwater to a drain that flows into the pool in the atrium (the original small recessed cooling pool by the sauna was later enlarged to approximately 3 x 5 m). She incorporated a wooden trellis into the lowered sloped part of the brick wall as a support for grapevines planted outside the wall. The building-technical quality of the house has been sufficiently verified by nearly four decades since its realization between 1979-1982. Růžena Žertová inhabited the house in its unchanged form until shortly before her death in October 2019.

With a limited selection of materials, the architect also had to grapple with the design of the interior. Despite this, she achieved a timeless solution - cork floors, a ceiling of pine wood, and cream-colored wool carpets complemented by white lime plaster, ceramic tiles with gentle facets, and bathroom tiles. She also designed and created the furniture and decorative elements, including light fixtures herself. A large pine table, complemented by a corner bench and chairs, dominates the dining room; the kitchen cabinets, which Žertová conceived quite atypically, also have wooden doors. From wood painted with Luxol, she assembled a wardrobe wall in the entrance hall and a built-in furniture block in the bathroom; she treated the cladding of the sauna walls and doors with alder wood. In addition to wood with Luxol paint, she also used another outdoor element in the hall – marble tiles. She applied marble on window sills and threshold strips of the glazed walls.

All small furniture was done in white: coffee and side tables, bookshelves, work tables, and built-in closets in the main living room and study. She covered the built-in corner sofa with white wool technical fabric, along with two armchairs. Storage spaces in the closet and larger bedroom were placed in niches; the white doors thus blend with the walls into a single whole. For handles, Žertová used brass sheet rings with white-painted wooden circular centers. The material for the furniture was acquired from the discarded production of the Rousínov factories. These systems based on the use of a 60 cm module were supplemented by original pieces of furniture from the apartment on Dvořákova street. From there come the low cabinets in deep blue, dining chairs from TON, a leather armchair from a common retail chain, as well as a prototype chair made according to the architect's design or a historical chair. The grand piano in the study refers to the musical tradition of the Žertová family. The author emphasized the unity of the interior with aluminum light fixtures made according to her own design. In addition to wall lights with white glass covers in spherical shape, they include illuminators that supplied to the Dílo store in the 1970s and 80s. A lamp with a large hemispherical shade above the coffee table was complemented by a smaller hanging lamp above the dining table.

Růžena Žertová concentrated her long-standing experience in designing department stores into the design and realization of her own house, but worked here with more subtle means of expression. The connection of the house with the surrounding natural environment (including the symbolic North American Jeffrey pine in the atrium), material and structural solutions of the building, proportions of the living space, and sauna as part of the interior reference, among other things, to modern Scandinavian architecture. Scandinavian residential buildings have been an inspiration for many domestic builders or architects who sought a new shape for the family house since the 1960s. The events in Finland, particularly the cities in the forest of Tapiola and Otaniemi, constructed between 1953 and 1964, garnered particular attention from the expert public. In the design of the residential complex of fourteen atrium houses in Tapiola from 1963 to 1965, authored by architect Pentti Ahola, there are clear parallels with the solution of Růžena Žertová's house: "[...] the houses have all spaces opened to the atrium, which creates a living garden. The open parts of the atrium are closed by an optical wall. The layout connects the bedroom and living wings with a space that contains the kitchen, dining area, and bathroom. In the opposite part, there is supplementary equipment, sauna, guest room, workshop." Thanks to the repetition of this spatial concept and the grouping of atrium buildings, Pentti Ahola was able to create a compact ensemble of family houses with their own gardens on a small area. Růžena Žertová utilized the advantages of this type of construction again in the post-November period in a half-dozen urban studies.

The text is an extended version of a study published in 2016 – see Petra Gajdová – Petr Klíma, Own Family House in Brno-Žabovřesky, in: Petr Klíma (ed.), Růžena Žertová. Architect of Houses and Things, Prague 2016, pp. 83-90.

Notes:

1 - Barbora Klímová, We Lived That Project: Interviews with Architects and Theorists, Prague 2011, p. 15.

2 - Archive of Růžena Žertová. Drawings for the house are dated to July 1978.

3 - In an interview with Barbora Klímová, Růžena Žertová clarified the reason for her eviction: "After a while, because it was a very old house, reconstruction was necessary. On that occasion, the state provided the house to Geodesy, so it could be repaired as its own residence. The inhabitants were evicted to apartments in panel buildings. For us, because we were politically unreliable, childless, and built the apartment ourselves, they did not even provide substitute accommodation." Klímová (note 1), p. 15.

4 - Růžena Žertová recalled that after inspecting the area, she stated that she would never want to build at that location. From the interview of Petra Gajdová and Petr Klíma with Růžena Žertová, June 23, 2010.

5 - According to Růžena Žertová, the role in this was played by the fact that the Office of the Chief Architect of the City of Brno, facing a number of "complaints and requests for the reclamation of the aforementioned plot", did not have the resources for the modification of the plot. Klímová (note 1), p. 15. Petra Gajdová, Architect Růžena Žertová (diploma thesis), Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University, Brno 2010, p. 66.

6 - "I knew that a family house on the given plot, due to its foundation on an unlevelled fill, and thus on piles, could not have more than one floor," claimed Žertová, and added: "It is a house for two people and for potential guests, so there had to be a bedroom for us, one for guests, a study, a living area, and a bathroom." Klímová (note 1), p. 16.

7 - Lukáš Kos - Alice Šimečková, Family House of Architect Růžena Žertová. Proposal for Declaration as a Cultural Monument, Brno 2018, n.p. Author's archive.

8 - The glass surfaces in combination with the orientation of the house can also positively affect the temperature inside. The architect stated that "large glazed areas have such heat reception that when it is sunny in winter, the heating does not even turn on." Klímová (note 1), p. 16. Similar glazing elements were also used in a later realization of the family house in Sokolnice.

9 - Ibidem.

10 - Kos - Šimečková (note 7).

11 - Ibidem.

12 - Ibidem.

13 - Ibidem.

14 - Klímová (note 1), p. 16.

15 - Probably the most significant domestic source of information about the architecture there was at that time the book by Vladislav Dlesk Contemporary Finnish Architecture, published in Prague in 1975. Architecture and design of Scandinavian countries were also the theme of occasional contributions in contemporary professional and popular-scientific periodicals (e.g., Ivan Horký, The Development of Modern Finnish Architecture, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIII, 1974, No. 1, pp. 37-40).

16 - Dlesk (note 11), pp. 42-43.

The determining premises for the design of the house, which visually concludes the development of the northwest front of the street, became the limited size of the plot, unstable subsoil, and also the assumption that the building would serve only two people. From these considerations, the concept of a single-story house based on reinforced concrete drilled piles and with an L-shaped floor plan emerged. The somewhat small plot, defined by the two wings of the house, was conceived by Žertová as an atrium. The overall layout was enclosed by a brick wall in the form of an incomplete square measuring 15 x 15 m. From the compact mass of the living areas, only the volume of the garage was allowed to protrude. In placing the house on the plot, the architect respected the orientation of the cardinal directions - the grassy atrium measuring 9 x 9 m faces south and offers views of the city, while the garage is situated on the northwest side of the plot towards the forest. Through this configuration, Žertová achieved sufficiently sunlit private spaces while simultaneously defining the building against the wooded slope.

The atrium played a key role in the spatial arrangement and layout of the house. Žertová oriented all living rooms and the bathroom towards it. The clear layout arises from the division of the house into two operating parts. In the arm facing the street bay in front of the house, Žertová placed the living area with a fireplace, kitchen, dining nook, and a study for herself and her husband. The architect reserved the second arm for the quiet part of the house - leading from the entrance hall, which is directly connected to both the garage and the adjoining storage room, is a closet with entrances to the bathroom with sauna, guest room, and bedroom.

Růžena Žertová achieved balanced spatial relationships within the building primarily through the proportions of the rooms in the communal part of the house, which has a width of 5.6 m. She positioned the floor level of the living space and study - while maintaining the same clear height of 2.5 m - 30 cm lower than the other rooms of the building (in contrast, she raised the level of the garage by 20 cm). The qualities of the flowing space of this wing, whose natural counterpart is the disciplined layout of the quiet part of the house, are further enhanced by the changing light conditions throughout the day. While the kitchen area, oriented towards the street, brings in northeast light, the living space opens with a glazed wall featuring fixed frameless glazing and an opening door wing to the southwest. With light, Růžena Žertová worked sensitively in other parts of the house as well. She illuminated the entrance hall with a frameless glazed window at the height of the entire floor next to the entrance door. Twice - in the living area and in the bedroom - she utilized a window reminiscent of a loophole, serving as a jewel of firmly glazed panels, which included both clear and cast structured glass. These small openings, in both cases, bring diffused daylight into the corner of the room (the window in the bedroom also emphasizes one of the two main axes of the house and allows it to be seen completely up to the glazing at the entrance door). The author also supported the luminosity of the space with glazed doors in all living rooms. In contrast, she left the northwest facade of the house adjacent to the forest path completely without windows.

Knowing that she would realize the house by herself, Žertová thoroughly considered not only the spatial and layout arrangement but also the structural solutions of the building. She succeeded in advancing beyond the usual frameworks of socialist construction - due to better thermal insulation properties, she designed the load-bearing walls as a sandwich of aerated concrete blocks, air gaps, and solid bricks. For the same reason, she modified the standard tilt windows measuring 1.5 m x 1.5 m, which were subsequently fitted to the outer face of the walls, for double glazing, and implemented underfloor heating in part of the interior. Žertová designed the ceiling structure from ceramic inserts placed into steel beams, the flat roof, which extends 45 cm beyond the building's footprint, as a double-shell. The "face" of the roof was equipped with vertically layered dark brown wooden cladding. With the same paint - a very popular Luxol at the time - she color-coordinated the fillings of openings and the wooden grid of the narrow strip of terrace bordering the bedroom wing of the house. In part of the atrium along the residential wing, as well as on the access sidewalk and in the windbreak on the other side of the house, she laid marble tiles imported from the then Yugoslavia. She directed rainwater to a drain that flows into the pool in the atrium (the original small recessed cooling pool by the sauna was later enlarged to approximately 3 x 5 m). She incorporated a wooden trellis into the lowered sloped part of the brick wall as a support for grapevines planted outside the wall. The building-technical quality of the house has been sufficiently verified by nearly four decades since its realization between 1979-1982. Růžena Žertová inhabited the house in its unchanged form until shortly before her death in October 2019.

With a limited selection of materials, the architect also had to grapple with the design of the interior. Despite this, she achieved a timeless solution - cork floors, a ceiling of pine wood, and cream-colored wool carpets complemented by white lime plaster, ceramic tiles with gentle facets, and bathroom tiles. She also designed and created the furniture and decorative elements, including light fixtures herself. A large pine table, complemented by a corner bench and chairs, dominates the dining room; the kitchen cabinets, which Žertová conceived quite atypically, also have wooden doors. From wood painted with Luxol, she assembled a wardrobe wall in the entrance hall and a built-in furniture block in the bathroom; she treated the cladding of the sauna walls and doors with alder wood. In addition to wood with Luxol paint, she also used another outdoor element in the hall – marble tiles. She applied marble on window sills and threshold strips of the glazed walls.

All small furniture was done in white: coffee and side tables, bookshelves, work tables, and built-in closets in the main living room and study. She covered the built-in corner sofa with white wool technical fabric, along with two armchairs. Storage spaces in the closet and larger bedroom were placed in niches; the white doors thus blend with the walls into a single whole. For handles, Žertová used brass sheet rings with white-painted wooden circular centers. The material for the furniture was acquired from the discarded production of the Rousínov factories. These systems based on the use of a 60 cm module were supplemented by original pieces of furniture from the apartment on Dvořákova street. From there come the low cabinets in deep blue, dining chairs from TON, a leather armchair from a common retail chain, as well as a prototype chair made according to the architect's design or a historical chair. The grand piano in the study refers to the musical tradition of the Žertová family. The author emphasized the unity of the interior with aluminum light fixtures made according to her own design. In addition to wall lights with white glass covers in spherical shape, they include illuminators that supplied to the Dílo store in the 1970s and 80s. A lamp with a large hemispherical shade above the coffee table was complemented by a smaller hanging lamp above the dining table.

Růžena Žertová concentrated her long-standing experience in designing department stores into the design and realization of her own house, but worked here with more subtle means of expression. The connection of the house with the surrounding natural environment (including the symbolic North American Jeffrey pine in the atrium), material and structural solutions of the building, proportions of the living space, and sauna as part of the interior reference, among other things, to modern Scandinavian architecture. Scandinavian residential buildings have been an inspiration for many domestic builders or architects who sought a new shape for the family house since the 1960s. The events in Finland, particularly the cities in the forest of Tapiola and Otaniemi, constructed between 1953 and 1964, garnered particular attention from the expert public. In the design of the residential complex of fourteen atrium houses in Tapiola from 1963 to 1965, authored by architect Pentti Ahola, there are clear parallels with the solution of Růžena Žertová's house: "[...] the houses have all spaces opened to the atrium, which creates a living garden. The open parts of the atrium are closed by an optical wall. The layout connects the bedroom and living wings with a space that contains the kitchen, dining area, and bathroom. In the opposite part, there is supplementary equipment, sauna, guest room, workshop." Thanks to the repetition of this spatial concept and the grouping of atrium buildings, Pentti Ahola was able to create a compact ensemble of family houses with their own gardens on a small area. Růžena Žertová utilized the advantages of this type of construction again in the post-November period in a half-dozen urban studies.

Petr Klíma

The text is an extended version of a study published in 2016 – see Petra Gajdová – Petr Klíma, Own Family House in Brno-Žabovřesky, in: Petr Klíma (ed.), Růžena Žertová. Architect of Houses and Things, Prague 2016, pp. 83-90.

Notes:

1 - Barbora Klímová, We Lived That Project: Interviews with Architects and Theorists, Prague 2011, p. 15.

2 - Archive of Růžena Žertová. Drawings for the house are dated to July 1978.

3 - In an interview with Barbora Klímová, Růžena Žertová clarified the reason for her eviction: "After a while, because it was a very old house, reconstruction was necessary. On that occasion, the state provided the house to Geodesy, so it could be repaired as its own residence. The inhabitants were evicted to apartments in panel buildings. For us, because we were politically unreliable, childless, and built the apartment ourselves, they did not even provide substitute accommodation." Klímová (note 1), p. 15.

4 - Růžena Žertová recalled that after inspecting the area, she stated that she would never want to build at that location. From the interview of Petra Gajdová and Petr Klíma with Růžena Žertová, June 23, 2010.

5 - According to Růžena Žertová, the role in this was played by the fact that the Office of the Chief Architect of the City of Brno, facing a number of "complaints and requests for the reclamation of the aforementioned plot", did not have the resources for the modification of the plot. Klímová (note 1), p. 15. Petra Gajdová, Architect Růžena Žertová (diploma thesis), Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University, Brno 2010, p. 66.

6 - "I knew that a family house on the given plot, due to its foundation on an unlevelled fill, and thus on piles, could not have more than one floor," claimed Žertová, and added: "It is a house for two people and for potential guests, so there had to be a bedroom for us, one for guests, a study, a living area, and a bathroom." Klímová (note 1), p. 16.

7 - Lukáš Kos - Alice Šimečková, Family House of Architect Růžena Žertová. Proposal for Declaration as a Cultural Monument, Brno 2018, n.p. Author's archive.

8 - The glass surfaces in combination with the orientation of the house can also positively affect the temperature inside. The architect stated that "large glazed areas have such heat reception that when it is sunny in winter, the heating does not even turn on." Klímová (note 1), p. 16. Similar glazing elements were also used in a later realization of the family house in Sokolnice.

9 - Ibidem.

10 - Kos - Šimečková (note 7).

11 - Ibidem.

12 - Ibidem.

13 - Ibidem.

14 - Klímová (note 1), p. 16.

15 - Probably the most significant domestic source of information about the architecture there was at that time the book by Vladislav Dlesk Contemporary Finnish Architecture, published in Prague in 1975. Architecture and design of Scandinavian countries were also the theme of occasional contributions in contemporary professional and popular-scientific periodicals (e.g., Ivan Horký, The Development of Modern Finnish Architecture, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIII, 1974, No. 1, pp. 37-40).

16 - Dlesk (note 11), pp. 42-43.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

4 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

oximorón

maxim

09.01.20 10:54

la poca bellezza

09.01.20 10:59

... (7:- D)...

šakal

10.01.20 09:39

celkom pekné retro

roman

14.01.20 12:07

show all comments