Family farm in Kostelec nad Černými lesy

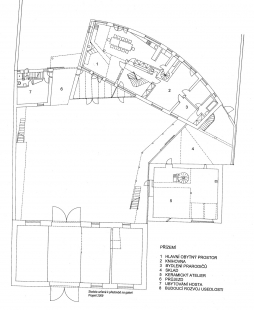

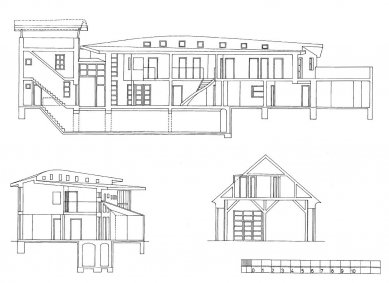

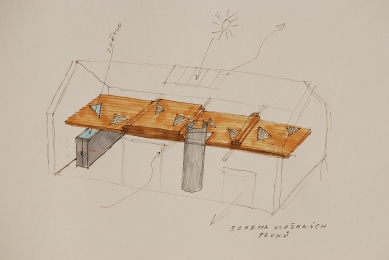

The client's requirement was to place family housing with a ceramics studio on a very nice plot on the edge of the central development of the city. I chose to add to the existing structure of the rear parcels of houses on Kostelecké Square, specifically in this location defined by barns with the new construction of the residential building itself, in a segmented structure complemented by a tower with an observation point, creating a closed unit. The tower and the mass of the main building are oriented against each other so that a covered passageway with a view into the garden is created between them, which parallels the passage in the barn. The interior spaces are designed to respect the relationship of the building to the sun and especially to the city (the castle, the church tower). Even the composition of the main building's mass, which has a segmented shape on the north side, is not arbitrary but opens views of the castle due to its retreat from the rear garden. The owners required some playful elements, which I welcomed – such as a secret underground passage from the house to the tower or the utilization of the stone wall in the main space of the house, which I ultimately resolved with a bridge and a gallery accessible to the maps collected by the owner. Moreover, the space is complemented by another element allowing connection between the upper floor and the ground floor. The gallery in front of the bedroom is a favorite place for the lady of the house.

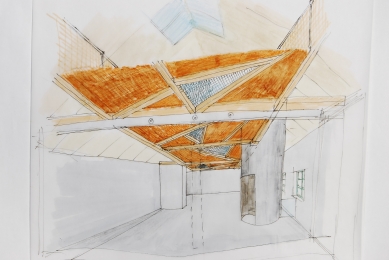

The front barn was originally intended for living, but after a change in the family structure, we are currently (2009) designing its modification into a ceramics gallery at the request of the client. Conversely, a small barn was purchased from the neighbor during the construction process when we discovered a woodworm issue and assumed that this problem would not be resolved by the neighbor. Here, we had to reproduce the original truss at the request of the heritage protectors. A ceramic studio function was then inserted into the newly reconstructed space. All buildings, except for the tower, are connected at the level of the first floor by a covered corridor, which includes a storage room for ceramics produced in the family company – the Czech Ceramic Manufactory. The new building is constructed from traditional materials – stone, wood, plaster. The roof of the new building is gray from pre-weathered titanium zinc, which corresponds in color to the gray of the concrete tiles on the entrance barn. The stone-sandstone used for the façade of the house and the garden's perimeter walls is sourced locally – from various devastated structures. I present the object after more than ten years, showing how the building has integrated into the terrain, including the inhabitation of the ceramics studio. The owners have become my friends, who still find the house inspiring even after years.

Nomination for the award of the Old Prague Club 2000.

NON-CUBIC ARCHITECTURE

The estate in Kostelec nad Černými Lesy is reviewed by Rostislav Švácha

The program of most Czech architects whose work I admire and often praise could perhaps be captured as the metaphysics of the box. In this theme, it is not difficult to trace the purist-functional roots, (1) some leading Czech architects of the last quarter-century, including younger and youngest ones, have managed to impart new meanings and find many new formal variations. Czech architects can create boxes, and they will showcase many beautiful and impressive examples.

However, the fondness for a simple rectangular frame conceals problems. When many people do something and do it for a long time, it may happen that the topic is completely exhausted and becomes a stereotype, banality, boredom. However, I do not yet blame the work of Czech architects for the fatigue from the box, nor do I consider it the main problem. What concerns me more is the fact that the almost obsessive squeezing of imagination into the box-like template of four walls and a flat roof diverts architects from what is happening behind those four walls, what is happening around their building. It seems to me - perhaps unjustly - as if the theme of the box lulls architects' interest in the environment, in the urban or natural landscape in which the box is to stand. It seems as if it deprives the architect of the desire to shape the context as well. I am not referring here to any excessive expansion of the architect's territorial competencies, as sought by the avant-garde utopists of the twenties or the regional planners of the forties. It would probably suffice for architects not to forget that alongside the box, other elements and fragments of the landscape and urban environment should also be spread out, with which the building can expand beyond its four walls. Perhaps it is me who is delivering a banality here, or conversely, dreaming of the impossible. However, I still cannot forget Frampton's lectures in Prague and Brno from December 1995, which continually returned to the lesson that the tasks of today's architecture should not only include the building itself. (2) That it is equally important to think about the garden and the landscape, as Barragán, Pikionis, Siza, Snozzi, or Ando have done, where you can often hardly tell whether they are garden architects or building architects. We could have taken a similar lesson from Stanislav Makarov's recent exhibition at the Fragner Gallery. And I am not sure whether the box, however magically and metaphysically conceived, is even suitable for such expansion beyond its precisely delineated volume.

The concept that Jan Línek chose for the completion of the estate in Kostelec nad Černými lesy during 1995-1998 probably does not solve the entire problem. However, it is certainly capable of showing one possible path.

The plot of the estate offers a typical - I would almost say "archetypical" – image of the edges of Czech towns and villages: a long garden, sealed closer to the center of the town by a transverse structure of a barn, and surrounded on the sides by stone walls. During the design phase, the clients also purchased a smaller barn at the northern edge of the plot and then inserted a ceramics workshop into it. To the barns, the architect added a complex set of new buildings: single-story and multi-story communication canopies made of wood, a large residential wing in an irregular polygon footprint, rounded towards the garden, covered with a cascade of metal roofs and equipped inside with a Raumplan living staircase hall, and finally, a stone tower with a segmented metal roof, a building so well constructed that we could easily mistake it for a remnant (never built) of medieval fortifications of Kostelec. (3)

The collage-like set of this fictional stronghold – a kind of modernized Roháček from Vláčil's film Markéta Lazarová – forms a closed circuit in its entirety. However, precisely by how thoroughly it avoids modern rectangular forms, this collection can better communicate with the surrounding development of the historic town and extend into the garden and the landscape. I would say that the main means of the landscape work of the architect here have become the stone walls surrounding the garden. The architect first had them disassembled in order to use their quality sandstone material for the construction of the tower and the opposite stone wall of the residential hall. However, he then rebuilt them. The walls allow the new construction to extend into the garden and towards the Black Forest on the horizon. On the contrary, the newly established pond in the enclosed courtyard has become a symbol of the backward expansion of nature or the garden into the space of the estate – which the architect's client rightly insisted upon. Wooden surfaces of the gates and communication canopies meet the stone masonry of the new construction, the wooden ceiling of the roof on the tower, and the wooden wrapping of the residential hall, which metaphorically dresses in another layer of plaster wrapping of the remaining residential rooms.

The effort to evade the "totalitarian" pressure of the rectangular axial grid – the pressure of the urban planning implications of the theme of the box – has accompanied Línek's work since the seventies, from the period of joint work with Vlad Milunič. In those times, the collage structures of the new L+M buildings were already associated with generous land art modifications of their environment. It seems to me that in their early architectural-urban collages and brikolážích, architects were not thinking so much about the formal experiments of the New York Five or the ancient Hadrian's Villa, which Colin Rowe then promoted as a model of non-totalitarian urbanism, (4) but rather about the irregular formations of Czech castles and fortresses with their defensive towers and ramparts. (5) Over time, this was joined by the study of Mencl's Folk Architecture in Czechoslovakia and the study of folkloric construction in the field. Vlad Milunič utilized this, for example, in the design of the cultural center in Sedlec from 1987-1989; Jan Línek was also inspired by it in his Kostelec estate. (6) Even in the seventies, Línek's (and Milunič's) unmistakable architectural style began to form, in its current form, perhaps with certain, though not essential, influences from early Frank Gehry. Línek would easily do without them. However, it seems worthwhile to him to manifest the brikoláž-like nature of his architectural method and his persistent polemic with the theme of the box, which Gehry has subjected to such thorough dismantling.

The box is a theme that guarantees a standard. Nothing significantly new can be invented with it, but nothing of substance can be spoiled either. Non-cubic architecture represents a much greater risk. Jan Línek belongs to the few Czech architects who have not only endured this risk but have also additionally utilized its expansive landscape-forming potential.

NOTES

1) The program of box architecture was most clearly defined around 1923 by Le Corbusier: "Simply a box that can be used as a house." And again, the same in the twenties: "The house is a box: the most important thing is the interior." – This seems to contradict the pioneer of organic architecture in the Czech Republic, Vít Obrtel, in 1930: "The transcendent cannot be enclosed in a matchbox."

2) Frampton develops this idea primarily in his reflections on the theme of critical regionalism. - See Kenneth Frampton, "Critical Regionalism: Modern Architecture and Cultural Identity". Architect XLIII, 1997, No. 7-8, pp. 54-56, and No. 9, pp. 32-34. The essay was translated from English by Petr Kratochvíl.

3) Jan Línek himself raises the question of whether he should have emphasized more that the tower is a new architectural work. However, achieving the impression or illusion that a new building that does not so overtly declare its "historicizing" character has been standing in its place since time immemorial is, in my view, an admirable achievement for a contemporary architect.

4) See Colin Rowe-Fred Koetter, "Collage City" (1975), in: Kate Nesbitt (ed.), Theorizing (...). An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965-1995. New York 1996, pp. 268-293. - Rowe and Koetter also introduced the term brikoláž into the language of architectural theory – the art of improvisation, dealing with a problem that exceeds our narrow specialization, while relying on the means and materials available at hand – which they borrowed from French philosopher and cultural anthropologist Lévi-Strauss. - See Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (1966). Prague 1996, p. 33. - In the eighties, the Ševčíks began using the term brikoláž in our country.

5) See e.g. New Encyclopedia of Czech Fine Arts, A-M, Prague 1995, p. 511.

6) The transformed model of the Kostelec estate became the granary house in Lažiště, or more precisely its floor plan. Jan Línek revealed this to me. - See Václav Mencl, Folk Architecture in Czechoslovakia. Prague 1980, p. 152.

The front barn was originally intended for living, but after a change in the family structure, we are currently (2009) designing its modification into a ceramics gallery at the request of the client. Conversely, a small barn was purchased from the neighbor during the construction process when we discovered a woodworm issue and assumed that this problem would not be resolved by the neighbor. Here, we had to reproduce the original truss at the request of the heritage protectors. A ceramic studio function was then inserted into the newly reconstructed space. All buildings, except for the tower, are connected at the level of the first floor by a covered corridor, which includes a storage room for ceramics produced in the family company – the Czech Ceramic Manufactory. The new building is constructed from traditional materials – stone, wood, plaster. The roof of the new building is gray from pre-weathered titanium zinc, which corresponds in color to the gray of the concrete tiles on the entrance barn. The stone-sandstone used for the façade of the house and the garden's perimeter walls is sourced locally – from various devastated structures. I present the object after more than ten years, showing how the building has integrated into the terrain, including the inhabitation of the ceramics studio. The owners have become my friends, who still find the house inspiring even after years.

Nomination for the award of the Old Prague Club 2000.

NON-CUBIC ARCHITECTURE

The estate in Kostelec nad Černými Lesy is reviewed by Rostislav Švácha

The program of most Czech architects whose work I admire and often praise could perhaps be captured as the metaphysics of the box. In this theme, it is not difficult to trace the purist-functional roots, (1) some leading Czech architects of the last quarter-century, including younger and youngest ones, have managed to impart new meanings and find many new formal variations. Czech architects can create boxes, and they will showcase many beautiful and impressive examples.

However, the fondness for a simple rectangular frame conceals problems. When many people do something and do it for a long time, it may happen that the topic is completely exhausted and becomes a stereotype, banality, boredom. However, I do not yet blame the work of Czech architects for the fatigue from the box, nor do I consider it the main problem. What concerns me more is the fact that the almost obsessive squeezing of imagination into the box-like template of four walls and a flat roof diverts architects from what is happening behind those four walls, what is happening around their building. It seems to me - perhaps unjustly - as if the theme of the box lulls architects' interest in the environment, in the urban or natural landscape in which the box is to stand. It seems as if it deprives the architect of the desire to shape the context as well. I am not referring here to any excessive expansion of the architect's territorial competencies, as sought by the avant-garde utopists of the twenties or the regional planners of the forties. It would probably suffice for architects not to forget that alongside the box, other elements and fragments of the landscape and urban environment should also be spread out, with which the building can expand beyond its four walls. Perhaps it is me who is delivering a banality here, or conversely, dreaming of the impossible. However, I still cannot forget Frampton's lectures in Prague and Brno from December 1995, which continually returned to the lesson that the tasks of today's architecture should not only include the building itself. (2) That it is equally important to think about the garden and the landscape, as Barragán, Pikionis, Siza, Snozzi, or Ando have done, where you can often hardly tell whether they are garden architects or building architects. We could have taken a similar lesson from Stanislav Makarov's recent exhibition at the Fragner Gallery. And I am not sure whether the box, however magically and metaphysically conceived, is even suitable for such expansion beyond its precisely delineated volume.

The concept that Jan Línek chose for the completion of the estate in Kostelec nad Černými lesy during 1995-1998 probably does not solve the entire problem. However, it is certainly capable of showing one possible path.

The plot of the estate offers a typical - I would almost say "archetypical" – image of the edges of Czech towns and villages: a long garden, sealed closer to the center of the town by a transverse structure of a barn, and surrounded on the sides by stone walls. During the design phase, the clients also purchased a smaller barn at the northern edge of the plot and then inserted a ceramics workshop into it. To the barns, the architect added a complex set of new buildings: single-story and multi-story communication canopies made of wood, a large residential wing in an irregular polygon footprint, rounded towards the garden, covered with a cascade of metal roofs and equipped inside with a Raumplan living staircase hall, and finally, a stone tower with a segmented metal roof, a building so well constructed that we could easily mistake it for a remnant (never built) of medieval fortifications of Kostelec. (3)

The collage-like set of this fictional stronghold – a kind of modernized Roháček from Vláčil's film Markéta Lazarová – forms a closed circuit in its entirety. However, precisely by how thoroughly it avoids modern rectangular forms, this collection can better communicate with the surrounding development of the historic town and extend into the garden and the landscape. I would say that the main means of the landscape work of the architect here have become the stone walls surrounding the garden. The architect first had them disassembled in order to use their quality sandstone material for the construction of the tower and the opposite stone wall of the residential hall. However, he then rebuilt them. The walls allow the new construction to extend into the garden and towards the Black Forest on the horizon. On the contrary, the newly established pond in the enclosed courtyard has become a symbol of the backward expansion of nature or the garden into the space of the estate – which the architect's client rightly insisted upon. Wooden surfaces of the gates and communication canopies meet the stone masonry of the new construction, the wooden ceiling of the roof on the tower, and the wooden wrapping of the residential hall, which metaphorically dresses in another layer of plaster wrapping of the remaining residential rooms.

The effort to evade the "totalitarian" pressure of the rectangular axial grid – the pressure of the urban planning implications of the theme of the box – has accompanied Línek's work since the seventies, from the period of joint work with Vlad Milunič. In those times, the collage structures of the new L+M buildings were already associated with generous land art modifications of their environment. It seems to me that in their early architectural-urban collages and brikolážích, architects were not thinking so much about the formal experiments of the New York Five or the ancient Hadrian's Villa, which Colin Rowe then promoted as a model of non-totalitarian urbanism, (4) but rather about the irregular formations of Czech castles and fortresses with their defensive towers and ramparts. (5) Over time, this was joined by the study of Mencl's Folk Architecture in Czechoslovakia and the study of folkloric construction in the field. Vlad Milunič utilized this, for example, in the design of the cultural center in Sedlec from 1987-1989; Jan Línek was also inspired by it in his Kostelec estate. (6) Even in the seventies, Línek's (and Milunič's) unmistakable architectural style began to form, in its current form, perhaps with certain, though not essential, influences from early Frank Gehry. Línek would easily do without them. However, it seems worthwhile to him to manifest the brikoláž-like nature of his architectural method and his persistent polemic with the theme of the box, which Gehry has subjected to such thorough dismantling.

The box is a theme that guarantees a standard. Nothing significantly new can be invented with it, but nothing of substance can be spoiled either. Non-cubic architecture represents a much greater risk. Jan Línek belongs to the few Czech architects who have not only endured this risk but have also additionally utilized its expansive landscape-forming potential.

NOTES

1) The program of box architecture was most clearly defined around 1923 by Le Corbusier: "Simply a box that can be used as a house." And again, the same in the twenties: "The house is a box: the most important thing is the interior." – This seems to contradict the pioneer of organic architecture in the Czech Republic, Vít Obrtel, in 1930: "The transcendent cannot be enclosed in a matchbox."

2) Frampton develops this idea primarily in his reflections on the theme of critical regionalism. - See Kenneth Frampton, "Critical Regionalism: Modern Architecture and Cultural Identity". Architect XLIII, 1997, No. 7-8, pp. 54-56, and No. 9, pp. 32-34. The essay was translated from English by Petr Kratochvíl.

3) Jan Línek himself raises the question of whether he should have emphasized more that the tower is a new architectural work. However, achieving the impression or illusion that a new building that does not so overtly declare its "historicizing" character has been standing in its place since time immemorial is, in my view, an admirable achievement for a contemporary architect.

4) See Colin Rowe-Fred Koetter, "Collage City" (1975), in: Kate Nesbitt (ed.), Theorizing (...). An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965-1995. New York 1996, pp. 268-293. - Rowe and Koetter also introduced the term brikoláž into the language of architectural theory – the art of improvisation, dealing with a problem that exceeds our narrow specialization, while relying on the means and materials available at hand – which they borrowed from French philosopher and cultural anthropologist Lévi-Strauss. - See Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (1966). Prague 1996, p. 33. - In the eighties, the Ševčíks began using the term brikoláž in our country.

5) See e.g. New Encyclopedia of Czech Fine Arts, A-M, Prague 1995, p. 511.

6) The transformed model of the Kostelec estate became the granary house in Lažiště, or more precisely its floor plan. Jan Línek revealed this to me. - See Václav Mencl, Folk Architecture in Czechoslovakia. Prague 1980, p. 152.

Rostislav Švácha

(Published in the magazine ARCHITEKT 24/98, p. 38)

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

23 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

první dojem

Lenka

19.02.09 09:28

romantismus zije:)

hetzer

19.02.09 09:17

Pěkné a známé,

Vích

19.02.09 09:42

libivost ?

abakus

20.02.09 10:35

Abakusovi

Jan Línek

20.02.09 08:12

show all comments