Colony New House

> Interwar exhibitions of contemporary housing

> Three-house by Bohuslav Fuchs

> Three-house by Jaroslav Grunt

> Villa by Jiří Kroha

> Duplex by Ernst Wiesner

> Duplex by Jan Víšek

> House by Jaroslav Syřiště

> Duplex by Miroslav Putna and Hugo Foltýn

> Duplex by Josef Štěpánek

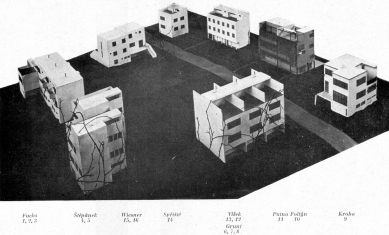

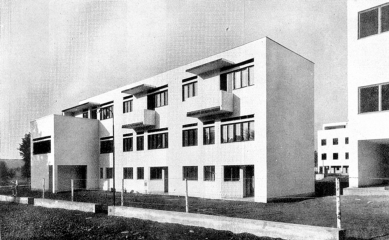

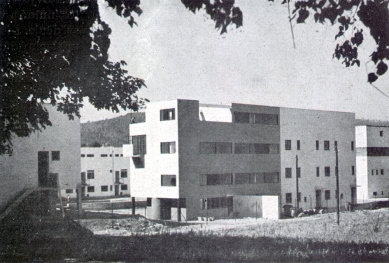

During the preparations for the Exhibition of Contemporary Culture at the Brno Exhibition Grounds, an exhibition of modern housing organized by Mies van der Rohe was opened at Weissenhof in Stuttgart. This exhibition quickly gained significant attention, prompting Brno builders František Uherka and Čeněk Ruller to suggest organizing a similar exhibition as part of the VSK. This idea was supported by the then Union of Czechoslovak Work. A plot of land was selected for the exhibition colony near the Brno exhibition ground at the foot of Wilson's forest. At the end of 1927, city architects Fuchs and Grunt carried out the parceling of the area. Nine mostly young Brno architects were invited. A total of 16 houses were built.

The authors here aimed to design functionalist houses with economical layouts, frequently using single-flight stairs and residential terraces. The main type is the economical row house. Most apartments are equipped with standardized built-in furniture by Jan Vaněk and his Housing Company Standart. A catalog was published for the exhibition (edited by Zdeněk Rossmann and Bedřich Václavek), including an extensive selection of theoretical articles by contemporary pioneers of functionalism, including Le Corbusier's Five Points. The exhibition was a significant experiment of its time and generated considerable interest.

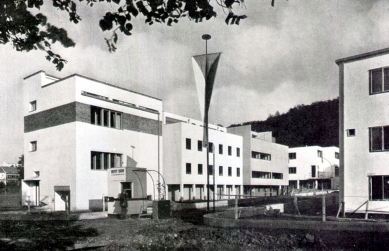

BOHUSLAV FUCHS designed a row house with a reinforced concrete skeleton structure utilizing prefabricated elements. Similar types of houses were proposed by JAROSLAV GRUNT and JAN VÍŠEK. ARNOŠT WIESNER, represented by a duplex, connected the apartment to the garden through an elevated terrace, which was characteristic for him at the time.

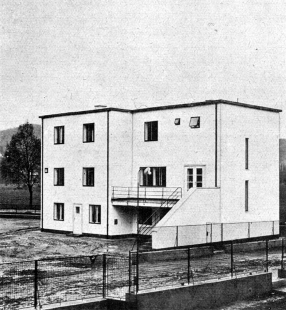

The oldest architect represented here, Prof. JAROSLAV SYŘIŠTĚ, presented an isolated and excellently designed house. He did not overlook his favorite motif - a formal brick band across the façade.

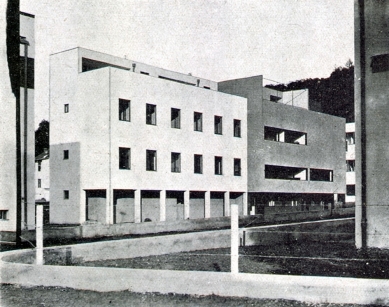

Very interesting and then quite shocking was the solution of two row houses by the youngest participants of the exhibition, HUGO FOLTÝN and MIROSLAV PUTNA. They were inspired by Le Corbusier in both exterior and interior. They employed continuous windows (Foltýn's façade was almost windowless), circular steel staircases, or roof terraces. Originally, their duplex was supposed to stand independently but was later connected to Víšek's house into one block.

A more demanding villa, which featured a large living room with a winter garden and terrace, was designed by JIŘÍ KROHA and the last exhibitor was Prague architect JOSEF ŠTĚPÁNEK.

As part of the housing exhibition at the VSK, one sample rental house was constructed directly at the exhibition (as an exhibit of the Union of Czechoslovak Work; architect Josef Havlíček), a pavilion for the School of Applied Arts in Prague with a shop and exhibition hall on the ground floor and an apartment with a residential terrace on the upper two floors (architect Pavel Janák), and a practically furnished caretaker's house of the exhibition ground by architect Oldřich Starý.

However, this venture was not successful for builders Uherka and Ruller - during the event, no house was sold.

Currently, the houses of Fuchs and Grunt are preserved almost in their original condition - these buildings, along with the aforementioned house of O. Starý, are heritage protected. Recently, one of architect Štěpánek's houses has been exemplary restored and now contrasts excellently with another house that has been completely devalued by extensions. Kroha's villa has also been altered to the extent that its original form is no longer discernible. The brick band of Prof. Syřiště has disappeared under red brick slip. Half of Víšek's house has been pushed towards the street, bringing it to the level of Putna's and Foltýn's houses. And this 'Le Corbusier' duplex is perhaps the most devalued. The band windows are replaced with ordinary ones (Foltýn's house does not lack romanticizing divisions of window panes into smaller sections with thin strips), and where chaotic roof extensions would perhaps have been kinder, a saddle roof would be more appropriate now.

COLONY “NEW HOUSE”

OLDŘICH STARÝ

A beautiful and characteristic feature of new architecture is the effort to approach life; to understand its needs and to create a new, more perfect environment for it. The problem of housing is one of the most pressing issues of today; for the development of architecture and for society, it is of great value that modern architects dedicate so much effort to overcoming all prejudices accumulated over the ages and to participating in the development of housing for modern people, moving away from cheap imitation of noble estates and superficial effects, and free of the pursuit of splendor and ostentatious appearances. The demands for light, sun, air, connecting the apartment with nature, striving for economy, simplicity, and order, a sense of simplification and regulation of all life, along with an insight into the human soul give architects the opportunities to create apartments that are simple, plain, functional, and beautiful, as beauty is not identical with splendor, as many people still mistakenly believe today. However, this creative effort would be in vain if it were not accompanied by the awareness and support of the residents, the entire society, which must urgently demand housing reform as a social and civilizing task; all the more so since there are so many who are homeless, such a hunger for apartments, and such a small percentage of newly created quarters meets today's needs and hygienic, functional, technical possibilities, not to mention the aesthetic, where conditions are the most lamentable. The most natural means to demonstrate and promote new housing efforts is an exhibition. The Brno exhibition of contemporary culture, which only had a few comprehensive attempts to solve this pressing modern issue, was therefore very suitably complemented by the establishment of the “New House” colony. Thanks to private entrepreneurs, builders Fr. Uherka and Č. Ruller from Brno, under the patronage of the Union of Czechoslovak Work, 16 detached and semi-detached family houses were built, designed by Brno architects Bohuslav Fuchs; Jaroslav Grunt. Jiří Kroha, Hugo Foltýn, Miroslav Putna, Jan Víšek, Jaroslav Syřiště, Arnošt Wiesner, and Prague's Josef Štěpánek.

The house, which can be inhabited immediately after the exhibition, is certainly the right economic and practical exhibition object. A model house, and that is what we are dealing with here, when the residents are not yet known, shows its great advantages only through repetition, in serial production. However, this can only be correctly achieved after testing; it is hardly possible to reach a type with a single attempt. Therefore, all attempts, if they are serious, responsible, and well thought out in internal operation, equipment, and construction to the last detail, have significance for development, not just for promotion but also for the factual and social aspects. Standing on concrete ground and not taking risks requires great courage in today's conditions, as already shown by the example of Stuttgart. It must also be realized that there are two crucial aspects of the housing issue, equally serious: reform-related and economic. Otherwise, all slogans about the social mission of architects will remain on paper. From this perspective, each similar venture must be viewed and appreciated for what it actually contributes to clarifying the problem. Beforehand, despite all contrary assertions, it must be stated that, except for isolated cases, the exhibition performed its task; it provided sufficient material for clarification; it is only to be regretted that the attendance from broader circles was relatively small due to the delayed opening of the exhibition.

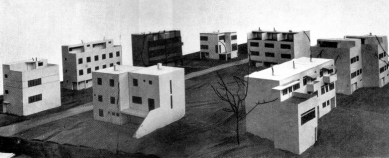

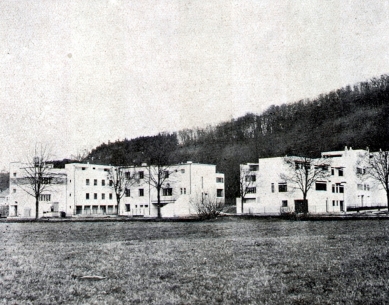

The location behind Pisárky at the foot of the hill with Wilson's forest in the background and a belt of meadows in front is very nice. The structure of the square, surrounded by family houses of a quiet architecture, was likely used for security reasons; it looks somewhat contrived and does not enhance the overall image. All objects raised one floor for groundwater, similar to Le Corbusier's house at the Stuttgart exhibition; this here then has a special justification, but also dispositional consequences, which were not completely taken into account everywhere (the possibility of only one access, terrace on the residential floor, etc.).

The program originally also determined the same price for the objects; later this was abandoned, which is to be regretted. Otherwise, most authors chose it quite similarly. On the ground floor, there are a laundry room, a cellar; somewhere also a room for a maid (some authors do not take this into account), a garage, a pantry, central heating (sometimes in the kitchen by the stove), a drying room. Some houses lack even that, which cannot be approved; perhaps it could be merged with the laundry room (located on the ground floor) for one family with good organization; central heating, laundry, and drying room in one room, as suggested by architect Putna, would likely not prove effective. On the first floor, there is a large living room with a dining area or a separable dining room, quite a small kitchen, W.C.; sometimes there is even a small study (architect Fuchs). On the second floor, there are bedrooms. The vertical system is therefore generally accepted as the only one acceptable today; likewise, the principle of separating sleeping from living as a hygienic principle (also as a non-residential kitchen); however, it does not need to be proclaimed as a canon; in larger families, bedrooms will be partially used for separate living (as in a hotel). It also does not seem correct that some architects designed only two bedrooms instead of three (parents, boys, girls; it is possible, of course, if it is forced, to count in this case that the father will sleep with the sons and the mother with the daughters; the separation of male and female bedrooms seems to imitate old noble customs). Only some authors have a dressing room or closets in the walls, surely a modern apartment necessity. It is also questionable whether it is practical to place a single closet in the house in the bathroom (especially considering a maid is expected); the bathroom will also be used as a morning washing area. It is surprising that some authors did not use flat roofs for the residential terrace (architects Fuchs, Wiesner, Kroha).

Situationally most houses meet requirements, especially the living rooms and bedrooms, although the task was not easy everywhere; direct faults exist in the houses of architect Putna and Foltýn (bedroom, dining room, study to the northwest). Roof terraces are poorly situated in some places (not protected from the north; sheltered corners).

Dispositional solutions do not follow a uniform line; there are different building styles, and different construction costs. Besides economical solutions for cheap houses, such as those built by architects Grunt, Víšek, Fuchs, and Syřiště, some solutions are considerably luxurious, even arbitrary. Relatively, the solutions for semi-detached houses approach most in scope and cost, although in principle and stair placement, they actually create three completely different cases. It is very correct to limit the space for stairs; however, if double-flight stairs are in the upper floor around the corridor (which is airier and nicer), no real savings are achieved against single-flight stairs. The steepness of the steps, especially if limited in width, has its limits; however, I would never advocate for slanted steps in a modern house. Double-flight staircases have the advantage of not separating the rooms and are airier than single-flight stairs placed between walls. Stairs in row houses generally lead out of the living room on the first floor, converting it into a hall. This has the disadvantage of losing heat through the staircase and a certain violation of intimacy in a single living room; architect Víšek tries to prevent this by enclosing the staircase after several steps; the stairway is then isolated, and direct connection to the room, which is essentially an English traditional reminiscence, loses its importance. Other issues with this stair placement include the time lost by going around the living room (e.g., from the bedroom to the kitchen or outside), lighting, etc. Single-flight stairs from the living room are justified only in cases where space is significantly gained, such as in row houses where no maid is expected. Ideally, to paralyze verticalism in a multi-story house, there should be a direct connection of stairs from the room to the room (from living room to bedroom), which, however, is unachievable for many reasons; all compromise solutions do not bring many advantages; here the situation is further complicated by the placement of the living room in the first floor. Access from the ground floor to the kitchen must not lead through the living room, and it must then be enclosed; this is a necessary requirement for sensible solutions to the task. If the household help is absent, a completely different floor plan follows; especially in row houses, where all facilities could be improved (central heating in the kitchen, cooking with gas, waste, etc.). The bedroom floor is mostly economically arranged and connected; direct access from the bedroom to the bathroom is almost everywhere missing, as is the connection of children's bedrooms to the parents' bedroom. Dispositional solutions diverge in H. Foltýn’s house; modeled on Le Corbusier's Stuttgart house, it connects the living space, extending through two floors, with bedrooms on a gallery lit only by small windows from the lower floor; to get to the second bedroom, one must exit to the gallery and descend a few steps; in addition, the architectural solution has unpleasant proportions, so the intended effect fails; a whole range of other criticisms could be raised (a column in front of the doors, spiral staircase, bed in a niche, etc.)

Constructively the houses are mostly made from Isostone blocks (Calofrig) with reinforced concrete columns around the cavities of the blocks and a central column. Lightweight partitions. The only house by J. Syřiště has normal brick walls. Windows of various kinds; inside-opening without a transom with double glazing, simple and practical, designed by J. Víšek. Elsewhere, standard double windows without transoms. A. Wiesner uses old windows that open outwards and inwards, perhaps for architectural reasons; this is not practical. Iron box sliding windows in M. Putna and H. Foltýn's house are poorly conceived. They are closed boxes, quite heavy to operate, non-opening (how would one clean the glass?), and mainly poorly sealing. Standard doors, plywood; the standardization of windows is still very far off in both dimensions and construction. Jan Víšek felt this when he advocated for standardized double-leaf windows of the same format as a deliberate sacrifice in appearance. However, the selected window is too narrow for today’s lighting and sunlight requirements. In our case, the necessity for double windows is surely a difficulty; sympathetic sliding windows, both horizontal and vertical, never open the entire opening and are still too massive; much more initiative work will be needed. Insulation of the new windows should not worsen today’s conditions (walls expand much more). Stairs are mostly of reinforced concrete, then wooden. Heating is primarily central, sometimes using the Kamino system in combination with the stove. The advantage lies in the simplicity of operation, while the disadvantages include dirt and heat in the kitchen; it would likely be necessary to enlarge the kitchen again, as J. Grunt does. Stoves are gas or combination. Waste mostly leads through the center of the building. Not enough attention was paid to simplifying the drainage (one waste pipe would suffice).

The appearance of the colony suffered from the sample arrangement of the blocks of space; with equal heights, flat roofs, and terraces, it still gives, despite the large variety among the authors and significantly different solutions, a fairly uniform impression. It was inappropriate to connect J. Víšek's houses with adjacent ones and sometimes the distances between objects are too small.

The three row houses by J. Grunt feature a very simple layout with a transversely placed staircase in the central tract with very steep steps, but sufficiently lit, and only two bedrooms. The bathroom, as in most objects, is not accessible from any bedroom, and the visibility from the kitchen to the living room is rather difficult. The layout is very economical and clear, the roof terrace is well arranged for both hot and colder days. Simple, expressive, and logical appearance. They have a large terrace on the ground floor, although a bit distant from the residential floors. A thoughtful and responsible attempt that is not too far from a true type. The same tendency is seen in two of Jan Víšek's row houses with a mentioned single-flight staircase along the long side of the building. The advantage of single-flight stairs virtually disappears in the corridor on the second floor. The layout is also economical, well organized. The roof terrace is correctly conceived, detailed design is reasonable. The appearance is predetermined by deliberately standardized double-leaf windows, giving it a certain austerity, which is modest and correct in proportions; in the living room, a continuous window would probably be more advantageous, altering the character of the building; however, the solution commendably arises from a constructive principle and from a unified economic effort. The appearance of the houses has certainly suffered from their close adjacency to neighboring ones.

The three semi-detached houses by Bohuslav Fuchs have single-flight stairs perpendicular to the front, which is fundamentally a single-tract system. The connection between the dining room and kitchen is similar to Grunt's, thus not too advantageous, and there are only two bedrooms, but they are conveniently interconnected. The system is also economical and the layout is clear, although the author does not propose a roof terrace but replaces it with balconies; the appearance is especially striking from the southern side. The decision among these three semi-detached house systems, determined by the location of the staircase, is not easy; Grunt's system seems the most economical (even counting the exit to the terrace). However, Víšek’s has the advantage of continuity of rooms and entrances at the cost of somewhat less economy. The row house of Miroslav Putna has some rooms poorly oriented, which is its main flaw, especially the dining room, the parents' bedroom, and two unnecessary rooms in the attic. The layout has double-flight stairs in the middle, and it is also simple, clear, and economical on both floors. The odd division of the bedroom likely prevents an elongated feeling in the room, and the upper lighting of the bathroom is unwarranted. The design of the roof with a covered corner is good, the appearance is light and pleasant. The neighboring row house by H. Foltýn has already been dismissed previously; one can doubt whether omitting a window in the first floor with such consequences for the interior was so necessary and advantageous for the appearance; the neighboring house does not support this. The layout has already been discussed in detail; for a cheap house in such a limited space, it is inappropriate even if all the mentioned flaws are avoided. The effect of the interior space through a one-story hall, a gallery, concrete consoles, and a spiral staircase (or perhaps just because of that?) ultimately failed; the exterior appeared tasteful and light, like Putna's neighboring house. The duplex by Josef Štěpánek created a unified irregular living space on the ground floor with an inserted staircase, visually interesting, that could surely be beautifully furnished and inhabited. It is a drawback that the stairs from the ground floor are not enclosed, making the semicircular landing of the comfortable double-flight stairs create unpleasant corners, that on the upper floor there are only two bedrooms and the terrace opens to the north. Its appearance is also interesting and prominent; the attempt is not yet fully developed; it has more aesthetic value. The duplex by Arnošt Wiesner with symmetric, somewhat distorted layouts has an entrance hall accessible from the terrace, which is reached by uncovered stairs, or from the basement through two entrances; this is certainly an advantage of the layout. The stairs are double-flight, semicircular; the layout of the upper floor consists of three bedrooms. The roof terrace is replaced with a large ground-floor terrace with stairs, and double-leaf windows (except for one), standardized, give the aesthetic an almost historical, dry character. Among the free houses, J. Syřiště's is far more economical with logical layouts. The drawback is that it has only two bedrooms, a toilet fitted into the bedroom, and the necessity for several waste pipes, which should not be the case. The roof terrace is good, the appearance marred by an incomprehensible strip of raw bricks. It was the only one furnished, and tastefully done. J. Kroha's house is considerably more luxurious. With a great deal of space, the stairs are unnecessarily cramped when only a hallway is next to them. On the ground floor, it has two large rooms that perform well; likewise, the large greenhouse window performs well both outside and inside. However, one must climb up and then down to the maid's room. The upper floor is unnecessarily complicated. Between three bedrooms, there is a hallway intended as a breakfast room, a relatively large dressing room and closet, and a bathroom with a very peculiar layout. The stairs in this noble comfort are cramped. The terrace faces north. The flat roof lacks a terrace. The appearance is moderate and tasteful.

The entire venture deserved greater attention from the professional public. It provides a very instructive attempt. And it is one of the few impulses in our environment to think through all the complex problems associated with housing construction: technical and constructive, operational, socio-economic, and aesthetic. It should find more frequent repetition in a more refined manner. And above all, it should educate the decisive circles on how difficult and responsible it is to build standard housing, how much work and serious scientific attempts from the best people must precede it, and that venturing into large projects without due preparation through such actions constitutes a risk to the national economy and social well-being, which still willfully ignore the most serious problems of the time and their appropriate solutions. And architects should be encouraged to work harder in all areas of residential construction, especially on constructive details, lest the new architecture find itself at the crossroads of romantic aestheticism, and the social task of architecture, which architects themselves proclaim, remains an empty proclamation.

> Three-house by Jaroslav Grunt

> Villa by Jiří Kroha

> Duplex by Ernst Wiesner

> Duplex by Jan Víšek

> House by Jaroslav Syřiště

> Duplex by Miroslav Putna and Hugo Foltýn

> Duplex by Josef Štěpánek

During the preparations for the Exhibition of Contemporary Culture at the Brno Exhibition Grounds, an exhibition of modern housing organized by Mies van der Rohe was opened at Weissenhof in Stuttgart. This exhibition quickly gained significant attention, prompting Brno builders František Uherka and Čeněk Ruller to suggest organizing a similar exhibition as part of the VSK. This idea was supported by the then Union of Czechoslovak Work. A plot of land was selected for the exhibition colony near the Brno exhibition ground at the foot of Wilson's forest. At the end of 1927, city architects Fuchs and Grunt carried out the parceling of the area. Nine mostly young Brno architects were invited. A total of 16 houses were built.

The authors here aimed to design functionalist houses with economical layouts, frequently using single-flight stairs and residential terraces. The main type is the economical row house. Most apartments are equipped with standardized built-in furniture by Jan Vaněk and his Housing Company Standart. A catalog was published for the exhibition (edited by Zdeněk Rossmann and Bedřich Václavek), including an extensive selection of theoretical articles by contemporary pioneers of functionalism, including Le Corbusier's Five Points. The exhibition was a significant experiment of its time and generated considerable interest.

BOHUSLAV FUCHS designed a row house with a reinforced concrete skeleton structure utilizing prefabricated elements. Similar types of houses were proposed by JAROSLAV GRUNT and JAN VÍŠEK. ARNOŠT WIESNER, represented by a duplex, connected the apartment to the garden through an elevated terrace, which was characteristic for him at the time.

The oldest architect represented here, Prof. JAROSLAV SYŘIŠTĚ, presented an isolated and excellently designed house. He did not overlook his favorite motif - a formal brick band across the façade.

Very interesting and then quite shocking was the solution of two row houses by the youngest participants of the exhibition, HUGO FOLTÝN and MIROSLAV PUTNA. They were inspired by Le Corbusier in both exterior and interior. They employed continuous windows (Foltýn's façade was almost windowless), circular steel staircases, or roof terraces. Originally, their duplex was supposed to stand independently but was later connected to Víšek's house into one block.

A more demanding villa, which featured a large living room with a winter garden and terrace, was designed by JIŘÍ KROHA and the last exhibitor was Prague architect JOSEF ŠTĚPÁNEK.

As part of the housing exhibition at the VSK, one sample rental house was constructed directly at the exhibition (as an exhibit of the Union of Czechoslovak Work; architect Josef Havlíček), a pavilion for the School of Applied Arts in Prague with a shop and exhibition hall on the ground floor and an apartment with a residential terrace on the upper two floors (architect Pavel Janák), and a practically furnished caretaker's house of the exhibition ground by architect Oldřich Starý.

However, this venture was not successful for builders Uherka and Ruller - during the event, no house was sold.

Currently, the houses of Fuchs and Grunt are preserved almost in their original condition - these buildings, along with the aforementioned house of O. Starý, are heritage protected. Recently, one of architect Štěpánek's houses has been exemplary restored and now contrasts excellently with another house that has been completely devalued by extensions. Kroha's villa has also been altered to the extent that its original form is no longer discernible. The brick band of Prof. Syřiště has disappeared under red brick slip. Half of Víšek's house has been pushed towards the street, bringing it to the level of Putna's and Foltýn's houses. And this 'Le Corbusier' duplex is perhaps the most devalued. The band windows are replaced with ordinary ones (Foltýn's house does not lack romanticizing divisions of window panes into smaller sections with thin strips), and where chaotic roof extensions would perhaps have been kinder, a saddle roof would be more appropriate now.

COLONY “NEW HOUSE”

OLDŘICH STARÝ

A beautiful and characteristic feature of new architecture is the effort to approach life; to understand its needs and to create a new, more perfect environment for it. The problem of housing is one of the most pressing issues of today; for the development of architecture and for society, it is of great value that modern architects dedicate so much effort to overcoming all prejudices accumulated over the ages and to participating in the development of housing for modern people, moving away from cheap imitation of noble estates and superficial effects, and free of the pursuit of splendor and ostentatious appearances. The demands for light, sun, air, connecting the apartment with nature, striving for economy, simplicity, and order, a sense of simplification and regulation of all life, along with an insight into the human soul give architects the opportunities to create apartments that are simple, plain, functional, and beautiful, as beauty is not identical with splendor, as many people still mistakenly believe today. However, this creative effort would be in vain if it were not accompanied by the awareness and support of the residents, the entire society, which must urgently demand housing reform as a social and civilizing task; all the more so since there are so many who are homeless, such a hunger for apartments, and such a small percentage of newly created quarters meets today's needs and hygienic, functional, technical possibilities, not to mention the aesthetic, where conditions are the most lamentable. The most natural means to demonstrate and promote new housing efforts is an exhibition. The Brno exhibition of contemporary culture, which only had a few comprehensive attempts to solve this pressing modern issue, was therefore very suitably complemented by the establishment of the “New House” colony. Thanks to private entrepreneurs, builders Fr. Uherka and Č. Ruller from Brno, under the patronage of the Union of Czechoslovak Work, 16 detached and semi-detached family houses were built, designed by Brno architects Bohuslav Fuchs; Jaroslav Grunt. Jiří Kroha, Hugo Foltýn, Miroslav Putna, Jan Víšek, Jaroslav Syřiště, Arnošt Wiesner, and Prague's Josef Štěpánek.

The house, which can be inhabited immediately after the exhibition, is certainly the right economic and practical exhibition object. A model house, and that is what we are dealing with here, when the residents are not yet known, shows its great advantages only through repetition, in serial production. However, this can only be correctly achieved after testing; it is hardly possible to reach a type with a single attempt. Therefore, all attempts, if they are serious, responsible, and well thought out in internal operation, equipment, and construction to the last detail, have significance for development, not just for promotion but also for the factual and social aspects. Standing on concrete ground and not taking risks requires great courage in today's conditions, as already shown by the example of Stuttgart. It must also be realized that there are two crucial aspects of the housing issue, equally serious: reform-related and economic. Otherwise, all slogans about the social mission of architects will remain on paper. From this perspective, each similar venture must be viewed and appreciated for what it actually contributes to clarifying the problem. Beforehand, despite all contrary assertions, it must be stated that, except for isolated cases, the exhibition performed its task; it provided sufficient material for clarification; it is only to be regretted that the attendance from broader circles was relatively small due to the delayed opening of the exhibition.

The location behind Pisárky at the foot of the hill with Wilson's forest in the background and a belt of meadows in front is very nice. The structure of the square, surrounded by family houses of a quiet architecture, was likely used for security reasons; it looks somewhat contrived and does not enhance the overall image. All objects raised one floor for groundwater, similar to Le Corbusier's house at the Stuttgart exhibition; this here then has a special justification, but also dispositional consequences, which were not completely taken into account everywhere (the possibility of only one access, terrace on the residential floor, etc.).

The program originally also determined the same price for the objects; later this was abandoned, which is to be regretted. Otherwise, most authors chose it quite similarly. On the ground floor, there are a laundry room, a cellar; somewhere also a room for a maid (some authors do not take this into account), a garage, a pantry, central heating (sometimes in the kitchen by the stove), a drying room. Some houses lack even that, which cannot be approved; perhaps it could be merged with the laundry room (located on the ground floor) for one family with good organization; central heating, laundry, and drying room in one room, as suggested by architect Putna, would likely not prove effective. On the first floor, there is a large living room with a dining area or a separable dining room, quite a small kitchen, W.C.; sometimes there is even a small study (architect Fuchs). On the second floor, there are bedrooms. The vertical system is therefore generally accepted as the only one acceptable today; likewise, the principle of separating sleeping from living as a hygienic principle (also as a non-residential kitchen); however, it does not need to be proclaimed as a canon; in larger families, bedrooms will be partially used for separate living (as in a hotel). It also does not seem correct that some architects designed only two bedrooms instead of three (parents, boys, girls; it is possible, of course, if it is forced, to count in this case that the father will sleep with the sons and the mother with the daughters; the separation of male and female bedrooms seems to imitate old noble customs). Only some authors have a dressing room or closets in the walls, surely a modern apartment necessity. It is also questionable whether it is practical to place a single closet in the house in the bathroom (especially considering a maid is expected); the bathroom will also be used as a morning washing area. It is surprising that some authors did not use flat roofs for the residential terrace (architects Fuchs, Wiesner, Kroha).

Situationally most houses meet requirements, especially the living rooms and bedrooms, although the task was not easy everywhere; direct faults exist in the houses of architect Putna and Foltýn (bedroom, dining room, study to the northwest). Roof terraces are poorly situated in some places (not protected from the north; sheltered corners).

Dispositional solutions do not follow a uniform line; there are different building styles, and different construction costs. Besides economical solutions for cheap houses, such as those built by architects Grunt, Víšek, Fuchs, and Syřiště, some solutions are considerably luxurious, even arbitrary. Relatively, the solutions for semi-detached houses approach most in scope and cost, although in principle and stair placement, they actually create three completely different cases. It is very correct to limit the space for stairs; however, if double-flight stairs are in the upper floor around the corridor (which is airier and nicer), no real savings are achieved against single-flight stairs. The steepness of the steps, especially if limited in width, has its limits; however, I would never advocate for slanted steps in a modern house. Double-flight staircases have the advantage of not separating the rooms and are airier than single-flight stairs placed between walls. Stairs in row houses generally lead out of the living room on the first floor, converting it into a hall. This has the disadvantage of losing heat through the staircase and a certain violation of intimacy in a single living room; architect Víšek tries to prevent this by enclosing the staircase after several steps; the stairway is then isolated, and direct connection to the room, which is essentially an English traditional reminiscence, loses its importance. Other issues with this stair placement include the time lost by going around the living room (e.g., from the bedroom to the kitchen or outside), lighting, etc. Single-flight stairs from the living room are justified only in cases where space is significantly gained, such as in row houses where no maid is expected. Ideally, to paralyze verticalism in a multi-story house, there should be a direct connection of stairs from the room to the room (from living room to bedroom), which, however, is unachievable for many reasons; all compromise solutions do not bring many advantages; here the situation is further complicated by the placement of the living room in the first floor. Access from the ground floor to the kitchen must not lead through the living room, and it must then be enclosed; this is a necessary requirement for sensible solutions to the task. If the household help is absent, a completely different floor plan follows; especially in row houses, where all facilities could be improved (central heating in the kitchen, cooking with gas, waste, etc.). The bedroom floor is mostly economically arranged and connected; direct access from the bedroom to the bathroom is almost everywhere missing, as is the connection of children's bedrooms to the parents' bedroom. Dispositional solutions diverge in H. Foltýn’s house; modeled on Le Corbusier's Stuttgart house, it connects the living space, extending through two floors, with bedrooms on a gallery lit only by small windows from the lower floor; to get to the second bedroom, one must exit to the gallery and descend a few steps; in addition, the architectural solution has unpleasant proportions, so the intended effect fails; a whole range of other criticisms could be raised (a column in front of the doors, spiral staircase, bed in a niche, etc.)

Constructively the houses are mostly made from Isostone blocks (Calofrig) with reinforced concrete columns around the cavities of the blocks and a central column. Lightweight partitions. The only house by J. Syřiště has normal brick walls. Windows of various kinds; inside-opening without a transom with double glazing, simple and practical, designed by J. Víšek. Elsewhere, standard double windows without transoms. A. Wiesner uses old windows that open outwards and inwards, perhaps for architectural reasons; this is not practical. Iron box sliding windows in M. Putna and H. Foltýn's house are poorly conceived. They are closed boxes, quite heavy to operate, non-opening (how would one clean the glass?), and mainly poorly sealing. Standard doors, plywood; the standardization of windows is still very far off in both dimensions and construction. Jan Víšek felt this when he advocated for standardized double-leaf windows of the same format as a deliberate sacrifice in appearance. However, the selected window is too narrow for today’s lighting and sunlight requirements. In our case, the necessity for double windows is surely a difficulty; sympathetic sliding windows, both horizontal and vertical, never open the entire opening and are still too massive; much more initiative work will be needed. Insulation of the new windows should not worsen today’s conditions (walls expand much more). Stairs are mostly of reinforced concrete, then wooden. Heating is primarily central, sometimes using the Kamino system in combination with the stove. The advantage lies in the simplicity of operation, while the disadvantages include dirt and heat in the kitchen; it would likely be necessary to enlarge the kitchen again, as J. Grunt does. Stoves are gas or combination. Waste mostly leads through the center of the building. Not enough attention was paid to simplifying the drainage (one waste pipe would suffice).

The appearance of the colony suffered from the sample arrangement of the blocks of space; with equal heights, flat roofs, and terraces, it still gives, despite the large variety among the authors and significantly different solutions, a fairly uniform impression. It was inappropriate to connect J. Víšek's houses with adjacent ones and sometimes the distances between objects are too small.

The three row houses by J. Grunt feature a very simple layout with a transversely placed staircase in the central tract with very steep steps, but sufficiently lit, and only two bedrooms. The bathroom, as in most objects, is not accessible from any bedroom, and the visibility from the kitchen to the living room is rather difficult. The layout is very economical and clear, the roof terrace is well arranged for both hot and colder days. Simple, expressive, and logical appearance. They have a large terrace on the ground floor, although a bit distant from the residential floors. A thoughtful and responsible attempt that is not too far from a true type. The same tendency is seen in two of Jan Víšek's row houses with a mentioned single-flight staircase along the long side of the building. The advantage of single-flight stairs virtually disappears in the corridor on the second floor. The layout is also economical, well organized. The roof terrace is correctly conceived, detailed design is reasonable. The appearance is predetermined by deliberately standardized double-leaf windows, giving it a certain austerity, which is modest and correct in proportions; in the living room, a continuous window would probably be more advantageous, altering the character of the building; however, the solution commendably arises from a constructive principle and from a unified economic effort. The appearance of the houses has certainly suffered from their close adjacency to neighboring ones.

The three semi-detached houses by Bohuslav Fuchs have single-flight stairs perpendicular to the front, which is fundamentally a single-tract system. The connection between the dining room and kitchen is similar to Grunt's, thus not too advantageous, and there are only two bedrooms, but they are conveniently interconnected. The system is also economical and the layout is clear, although the author does not propose a roof terrace but replaces it with balconies; the appearance is especially striking from the southern side. The decision among these three semi-detached house systems, determined by the location of the staircase, is not easy; Grunt's system seems the most economical (even counting the exit to the terrace). However, Víšek’s has the advantage of continuity of rooms and entrances at the cost of somewhat less economy. The row house of Miroslav Putna has some rooms poorly oriented, which is its main flaw, especially the dining room, the parents' bedroom, and two unnecessary rooms in the attic. The layout has double-flight stairs in the middle, and it is also simple, clear, and economical on both floors. The odd division of the bedroom likely prevents an elongated feeling in the room, and the upper lighting of the bathroom is unwarranted. The design of the roof with a covered corner is good, the appearance is light and pleasant. The neighboring row house by H. Foltýn has already been dismissed previously; one can doubt whether omitting a window in the first floor with such consequences for the interior was so necessary and advantageous for the appearance; the neighboring house does not support this. The layout has already been discussed in detail; for a cheap house in such a limited space, it is inappropriate even if all the mentioned flaws are avoided. The effect of the interior space through a one-story hall, a gallery, concrete consoles, and a spiral staircase (or perhaps just because of that?) ultimately failed; the exterior appeared tasteful and light, like Putna's neighboring house. The duplex by Josef Štěpánek created a unified irregular living space on the ground floor with an inserted staircase, visually interesting, that could surely be beautifully furnished and inhabited. It is a drawback that the stairs from the ground floor are not enclosed, making the semicircular landing of the comfortable double-flight stairs create unpleasant corners, that on the upper floor there are only two bedrooms and the terrace opens to the north. Its appearance is also interesting and prominent; the attempt is not yet fully developed; it has more aesthetic value. The duplex by Arnošt Wiesner with symmetric, somewhat distorted layouts has an entrance hall accessible from the terrace, which is reached by uncovered stairs, or from the basement through two entrances; this is certainly an advantage of the layout. The stairs are double-flight, semicircular; the layout of the upper floor consists of three bedrooms. The roof terrace is replaced with a large ground-floor terrace with stairs, and double-leaf windows (except for one), standardized, give the aesthetic an almost historical, dry character. Among the free houses, J. Syřiště's is far more economical with logical layouts. The drawback is that it has only two bedrooms, a toilet fitted into the bedroom, and the necessity for several waste pipes, which should not be the case. The roof terrace is good, the appearance marred by an incomprehensible strip of raw bricks. It was the only one furnished, and tastefully done. J. Kroha's house is considerably more luxurious. With a great deal of space, the stairs are unnecessarily cramped when only a hallway is next to them. On the ground floor, it has two large rooms that perform well; likewise, the large greenhouse window performs well both outside and inside. However, one must climb up and then down to the maid's room. The upper floor is unnecessarily complicated. Between three bedrooms, there is a hallway intended as a breakfast room, a relatively large dressing room and closet, and a bathroom with a very peculiar layout. The stairs in this noble comfort are cramped. The terrace faces north. The flat roof lacks a terrace. The appearance is moderate and tasteful.

The entire venture deserved greater attention from the professional public. It provides a very instructive attempt. And it is one of the few impulses in our environment to think through all the complex problems associated with housing construction: technical and constructive, operational, socio-economic, and aesthetic. It should find more frequent repetition in a more refined manner. And above all, it should educate the decisive circles on how difficult and responsible it is to build standard housing, how much work and serious scientific attempts from the best people must precede it, and that venturing into large projects without due preparation through such actions constitutes a risk to the national economy and social well-being, which still willfully ignore the most serious problems of the time and their appropriate solutions. And architects should be encouraged to work harder in all areas of residential construction, especially on constructive details, lest the new architecture find itself at the crossroads of romantic aestheticism, and the social task of architecture, which architects themselves proclaim, remains an empty proclamation.

Stavba VII, 1928-1929, s. 97-103

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

11 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

FOTODOKUMENTACE

Marek Kundrata

03.05.06 12:03

destrukce

kundrata

03.05.06 12:56

RE: destrukce

Tina28

24.01.07 07:52

Fuchsův trojdům

Martin Ryšavý

12.09.07 06:43

Fuchsův vlastní dům

Petr Šmídek

12.09.07 07:58

show all comments