Gateway Arch

The idea for the memorial to the settlement of the American West was conceived in 1933 in the mind of Dr. Luther Ely Smith, a lawyer and public figure from St. Louis. He often said: “If someone disagrees with you, it is because you have not explained your idea sufficiently.” In any case, it took another 14 years before an architectural competition was announced for this monument.

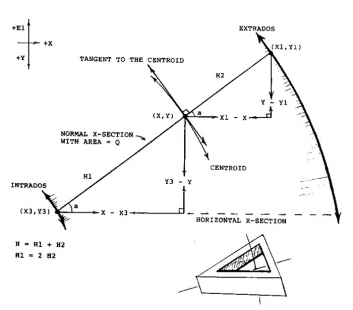

The competition proposal by the then 37-year-old architect Eero Saarinen defeated 171 other competitors, including his own father, and the jury called his work “a work of genius.” However, the chairman of the National Commission of Arts declared that Mussolini was considering building a similar arch at the Fascist Exhibition in Rome in 1942. “That is ridiculous,” Saarinen objected, “to assume that the basic form, which derives from the shapes of nature, has any ideological ties. The Egyptian obelisk was built by slaves, and the same shape is found in the Washington Monument.” The uproar surrounding the proposal slowly faded, but the project was delayed by other circumstances for another 14 years. The Korean War was draining the U.S. treasury. Saarinen and his team spent another eight years working on the design of the structure and developing the final shape. Saarinen felt that the curve of the arch was still not quite right. The final form, designed along with Hannskarl Mandel, a structural engineer from Saarinen's design team, was based on the theoretical shape of a catenary curve linking various weights as anticipated by the narrowing shape of the arch. It was a minor detail that was difficult to calculate, but it added a visual lightness to the final shape blended with the energy of nature.

Finally, on June 27, 1962, nearly a year after Saarinen's death, construction of the foundation structures began, approximately 15 feet below ground level.

A Pittsburgh factory began producing triangular steel components and transported them by rail to the construction site in St. Louis. According to engineering calculations, the top of the arch would sway 45 centimeters due to the wind. The construction was executed in such a way that both legs of the arch were built simultaneously. Instead of cranes, rails were used, laid on the outer side of the arch's structure that rose upward along with the structure itself. The concern that the two parts would not meet at the top persisted until the end. The work of laborers inside the arch's structure proved to be very difficult, and the construction company ultimately had to install air conditioning due to the unbearable heat. There was also a problem with feelings of claustrophobia while working inside the triangular ribs. In 1964, civil rights activists protested due to the lack of any Black workers on the construction site. In any case, there were no serious tragedies during the entire construction period. The biggest injury was a broken leg. Kenneth Kolkmeier, the project manager, said: “During the entire time, we did not have an unsolvable situation.”

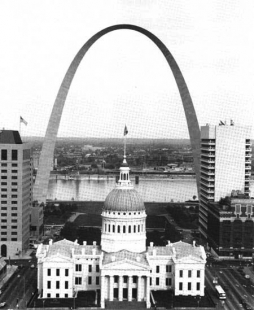

The construction was completed on October 28, 1965, exactly 32 years after the idea for the monument was conceived, 18 years after Saarinen's design won the competition, and 4 years after the author's death. The final version is 12 meters taller and wider than the competition design, which was modified continuously over the span of 15 years. The Gateway Arch can be seen from a great distance. Just as the Eiffel Tower is for Paris, so is the Gateway Arch for St. Louis.

The structure stands 192 meters tall and is 192 meters wide at its widest point; it is the tallest object in the city. Its cross-section is in the shape of a triangle, with sides measuring 16.5 meters at the base and 5.2 meters at the top of the arch. Each wall is a reinforced concrete shell (up to 91 meters high) and a carbon steel structure clad in stainless steel plates. The interior of the cross-section is hollow with an original transport system installed to carry visitors to the observation deck at the top.

Inside the arch there are also emergency exit staircases for the emergency use of the building.

At the base of the Arch, there is a visitor center, accessible by a long ramp from the park area. Here is the Museum of Westward Expansion, an exhibition on the history of the St. Louis waterfront, as well as boarding and disembarking areas for the cabins that transport visitors to the top of the arch. The Tucker Theatre, completed in 1968 and renovated 30 years later, has a capacity of 285 seats and shows the documentary "Monument to the Dream" about the construction of the Arch. The Odyssey Theatre was completed in 1993 and has 255 seats. Here, films are screened in an alternating cycle.

At the time of completion, the only access to the top was by climbing over a thousand stairs. Since 1968, the Arch has had a unique cabin transport system. Individual cabins are for five people. They are connected in trains of eight cabins. The journey upwards takes 4 minutes; the return trip takes one minute less.

The observation area at the top of the arch has small windows that are almost invisible from the ground. Visitors can look out into the vast distance across the Mississippi River to the west and the east. In the past, St. Louis was the last outpost of settled civilization before entering the Wild West.

The competition proposal by the then 37-year-old architect Eero Saarinen defeated 171 other competitors, including his own father, and the jury called his work “a work of genius.” However, the chairman of the National Commission of Arts declared that Mussolini was considering building a similar arch at the Fascist Exhibition in Rome in 1942. “That is ridiculous,” Saarinen objected, “to assume that the basic form, which derives from the shapes of nature, has any ideological ties. The Egyptian obelisk was built by slaves, and the same shape is found in the Washington Monument.” The uproar surrounding the proposal slowly faded, but the project was delayed by other circumstances for another 14 years. The Korean War was draining the U.S. treasury. Saarinen and his team spent another eight years working on the design of the structure and developing the final shape. Saarinen felt that the curve of the arch was still not quite right. The final form, designed along with Hannskarl Mandel, a structural engineer from Saarinen's design team, was based on the theoretical shape of a catenary curve linking various weights as anticipated by the narrowing shape of the arch. It was a minor detail that was difficult to calculate, but it added a visual lightness to the final shape blended with the energy of nature.

Finally, on June 27, 1962, nearly a year after Saarinen's death, construction of the foundation structures began, approximately 15 feet below ground level.

A Pittsburgh factory began producing triangular steel components and transported them by rail to the construction site in St. Louis. According to engineering calculations, the top of the arch would sway 45 centimeters due to the wind. The construction was executed in such a way that both legs of the arch were built simultaneously. Instead of cranes, rails were used, laid on the outer side of the arch's structure that rose upward along with the structure itself. The concern that the two parts would not meet at the top persisted until the end. The work of laborers inside the arch's structure proved to be very difficult, and the construction company ultimately had to install air conditioning due to the unbearable heat. There was also a problem with feelings of claustrophobia while working inside the triangular ribs. In 1964, civil rights activists protested due to the lack of any Black workers on the construction site. In any case, there were no serious tragedies during the entire construction period. The biggest injury was a broken leg. Kenneth Kolkmeier, the project manager, said: “During the entire time, we did not have an unsolvable situation.”

The construction was completed on October 28, 1965, exactly 32 years after the idea for the monument was conceived, 18 years after Saarinen's design won the competition, and 4 years after the author's death. The final version is 12 meters taller and wider than the competition design, which was modified continuously over the span of 15 years. The Gateway Arch can be seen from a great distance. Just as the Eiffel Tower is for Paris, so is the Gateway Arch for St. Louis.

The structure stands 192 meters tall and is 192 meters wide at its widest point; it is the tallest object in the city. Its cross-section is in the shape of a triangle, with sides measuring 16.5 meters at the base and 5.2 meters at the top of the arch. Each wall is a reinforced concrete shell (up to 91 meters high) and a carbon steel structure clad in stainless steel plates. The interior of the cross-section is hollow with an original transport system installed to carry visitors to the observation deck at the top.

Inside the arch there are also emergency exit staircases for the emergency use of the building.

At the base of the Arch, there is a visitor center, accessible by a long ramp from the park area. Here is the Museum of Westward Expansion, an exhibition on the history of the St. Louis waterfront, as well as boarding and disembarking areas for the cabins that transport visitors to the top of the arch. The Tucker Theatre, completed in 1968 and renovated 30 years later, has a capacity of 285 seats and shows the documentary "Monument to the Dream" about the construction of the Arch. The Odyssey Theatre was completed in 1993 and has 255 seats. Here, films are screened in an alternating cycle.

At the time of completion, the only access to the top was by climbing over a thousand stairs. Since 1968, the Arch has had a unique cabin transport system. Individual cabins are for five people. They are connected in trains of eight cabins. The journey upwards takes 4 minutes; the return trip takes one minute less.

The observation area at the top of the arch has small windows that are almost invisible from the ground. Visitors can look out into the vast distance across the Mississippi River to the west and the east. In the past, St. Louis was the last outpost of settled civilization before entering the Wild West.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

3 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

??

Petr Hill -- www.PetrHill.webz.cz

22.04.06 11:05

karbonová ocel

Petr Šmídek

22.04.06 03:42

dekuji

Petr Hill -- www.PetrHill.webz.cz

23.04.06 08:51

show all comments