Parish Church St. Fronleichnam

Corpus Christi Church

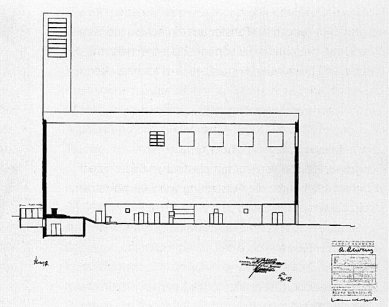

The Aachen Corpus Christi Church is the most famous and simultaneously the most extensively and thoroughly documented work of Rudolf Schwarz from the era of the School of Arts and Crafts. The existence of numerous conceptual sketches, design variations, floor plans, and perspectives allows a glimpse into the design work of a community of craftspeople, whose systematization has been notably addressed by recent research. In all planning, the basic principle remains the polarity of an elongated, cuboid structure and a towering campanile. Initially variable is also the connection of a low side nave (parallel or angular) and the issue of light guidance. Preliminary stages included a separation row of support columns, as well as side, end, or facade walls with long-drawn light slats.

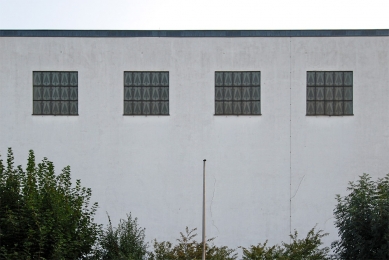

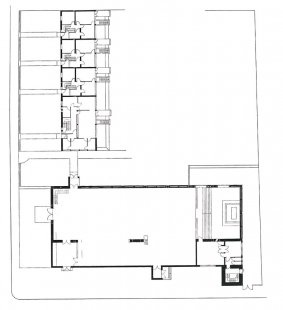

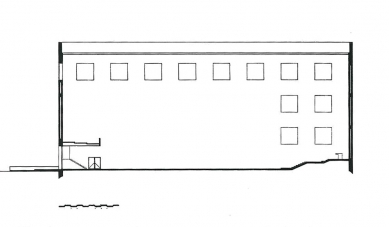

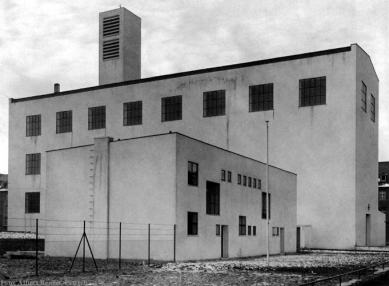

Finally, the execution chooses the strictest of forms, a horizontal rectangular cuboid (length 47 meters, width 13 meters, height 21 meters) with slightly gable-shaped narrow sides, with the interior area featuring a completely free altar wall, as well as an upper band of light composed of square windows that are only led down in two rows to the floor in the altar area of the northeastern long wall. The low side chapel (as a confessional and Stations of the Cross chapel) is separated from the main room only by a four-meter-wide pillar that carries the pulpit. The square bell tower, 40 meters high, is placed next to the side nave extended to the sacristy. The narrow iron bridge connecting the tower and the main ship in airy height acts as an ironic reminiscence to the pilgrims' bridge of the Aachen Cathedral. The low parish house extends on the other side of the church. The weekday entrance is located at the lower part of the side nave formed into a forecourt (baptistry); from there, one enters a low zone into the high, bright main room.

The appreciation of the church as a spiritual-religious building was initially conducted less by Schwarz himself than by his interpreters such as Romano Guardini or Hans Karlinger. Terms such as poverty and asceticism, emptiness as divine fullness, silent presence of God, or space for working Christians are already more advanced, strongly interpretative interpretations; Schwarz expressed himself in 1930 still rather formally describing: he wanted to "set a dominant in the disorder," and initially react to the loss of the old architectural iconography with the new forms of the time. The "artistic theme of this church (is) indeed the 'box';" the growing sequence of spaces corresponds to the growth of the idea.

St. Corpus Christi also gained great significance due to its unified furnishings, through which it could be elevated to the rank of a new total work of art. Its basis would again be the common design impulse of the Aachen "building lodge," yet Schwarz appears here as the spiritual leading force that gathers the individual masters around a common concept. As he increasingly refined his designs, some works by employees had to be set aside. Ultimately, Schwarz completely dispensed with monumental painting and the polychromy of the space, limiting himself to the contrast of black marble and light, white plaster (for what is "earth" or "yearns from it"). The liveliness of the marble with its fine white veins is particularly evident on the pillar of the side nave, where Schwarz has offset the different line structures of the slabs against each other. The free wall behind the tiered altar has always been one of the particularly eagerly discussed places in the church: Already in 1930, Wendung had sketched a strict, monumental figure of Christ for the wall; in the early 1940s, a painted decoration was finally to be implemented, yet to this day this wall—surrounded by interpretations and anecdotes—has been able to maintain its monumental character. Surely Schwarz had this construction in mind when he spoke in 1930 of the new ornamentation of the human body in the empty spaces ("these spaces hope for beautiful people") or confessed in 1936/37: "God is above. The empty space between the table and zenith is his throne."

Only in retrospect does Schwarz engage more closely with the central theme of the "Body of the Lord" ("Corpus Christi") - the corporeal unity of the people and the Lord realized in the church - whereby he represses or brings to a close the obvious thought of a procession or pathway church, seeing it "calm at the achieved goal." Without having explicitly referred to it, he likely connects these thoughts back to his writing "On the Construction of the Church" (1938), especially referencing the "Holy Path of the Fourth Plan." The church, which was rejected by the mayor and church authorities, positively acknowledged by the city's art council but ultimately built without episcopal approval, is still the most coherent structure of the Aachen school despite some inventory losses and additions. This is also due to the communal furnishings: the altar, pulpit, consecration crosses, baptismal font, and the hanging soffits all trace back to Schwarz. Schwippert designed the furniture, later also the organ prospect (1940); altar candelabra, everlasting light, and Easter candleholder come from Fritz Schwerdt, a collaborator of Anton Schickeis, as does the first chalice with the rock crystal nodus; Anton Schickel himself designed the square rock crystal monstrance, his student Hubert Dohmen the thurible and a ciborium (the latter according to designs by Schwarz); the processional cross was crafted by Wilhelm Giesbert, the liturgical vestments by Wilhelm Rupprecht, the church banners by Anton Wendung. Wilhelm Rupprecht also created a large-scale embroidered Stations of the Cross for the side nave (as well as a Marian image) from 1930 to 1936. The small enameled standing cross on the altar, which had originally still been a pure metal box, was covered by Schwerdt only in the 1950s; the ivory corpus was created by Minkenberg pupil Walter Ditsch. The altar cross was entirely sufficient for Rudolf Schwarz as a "designation of the space."

One of the major, unexecuted projects remained Wendung's lightly colored, geometric stained glass window designs, which developed a serial grid ornament from horizontal rectangular shapes. However, in the end, Schwarz opted for windows made of simple industrial glass. Even regarding the photographs by Albert Renger-Patzsch, which he highly valued and recognized as particularly important for the presentation of his architecture, Schwarz did not refrain from conveying his specific wishes and corrections regarding motif and viewpoint to his master colleague.

The fundamental renouncement of plastic ornamentation was already abandoned in 1931 with the establishment of two wooden, colorfully framed saint figures. Their stylized pathos asserts itself no more in the strictness of the space than the inevitably decorative ingredients of the most recent time, among which the new celebrant altar erected after the demolition of the old communion rail stands out particularly. As a monument in the working-class suburb Rothe Erde, the building remained groundbreaking for all modern architects. Even in 1957, Hermann Bauer confessed: "In last nakedness, architecture stood here, the shell of a space, composed with perfect measure, serving the primal element of light guidance to the cult and the sense of God's house."

Notes:

42 - Cf. Pehnt/Strohl, pp. 70ff., WVZ No. 12; Britta Giebeler, Sacred Total Works of Art, Weimar 1996, pp. 159ff.

43 - This results in a height increase from the parish house over the church to the tower. In 1936, Hanns Schwippert extended the parish house wing but transformed the original, lined window band into a block-like window arrangement. The small entrance door with a windbreak on the southwest side of the side nave has now disappeared.

44 - Cf. R.S., Corpus Christi Church, in: Die Schildgenossen, 11, 1931, No. 3, pp. 284f. An aerial photo already shows the shift towards an urban regularity in the settlement "Im Panne-schopp," which emerged shortly after St. Corpus Christi. 45 H. Schwippert strongly opposed a planned altar painting by H. Krahforst (May 26, 1941, Bishop's Diocesan Archive Aachen, file St. Corpus Christi, 21). See also A. Brecher (op. cit., Note 52), pp. 90 f. and the illustration of an interim tapestry (loc. cit., p. 84). 46 On the question of a possible theme for a painting on the altar wall, Schwarz ironically responded with a motif from Genesis: "In the beginning, the earth was void and empty." (according to Prof. Steinbach, in: M. Sundermann, op. cit., 1981, p. 119) 47 - Cf. R.S., On the Constitution of a Workshop School, 1930, p. 18.

48 - Quoted R.S., Altar, in: Die Schildgenossen, 16, 1936/37,5. 137.

49 - R.S., Church Building, pp. 16, 20.

50 - Cf. also his schematic drawings from the fourth plan (the Holy Path), p. 78 as well as the juxtaposition of drawing and church in: R.S., Thinking and Building, Heidelberg 1963, pp. 44/45.

51 - See August Brecher, St. Corpus Christi, Aachen 1997, pp. 15-29. The (perhaps precautionary) advice to forgo submitting a building committee proposal was formally justified by the art council with the church's location in a "not protected area by local statute" (STA, OB Reg. 181). See also Brecher's extensive collection of positive and negative voices on the new building (pp. 30-50). A pamphlet also appeared in the "Westdeutschen Grenzblatt" (predecessor of the "Westdeutschen Beobachters"), No. 58, 1930. Despite the involvement of the structural engineer Prof. Pirlet, the new construction method sometimes led to technical problems: In the first ringing of St. Corpus Christi, the "bridge" collapsed, and during a storm, the roof of the Social Women's School flew away. (Communication M. Getz) 52 - R. Schwarz wanted to use "light not as a lamp, but as brightness, as a luminous space" (Die Schildgenossen, 1931, p. 286).

53 - The chalice "created in agreement with Rudolf Schwarz" (Yearbook for Christian Art, 1957/58, p. 11) was recreated for exhibition purposes after the war (Suermondt-Ludwig Museum, Aachen). A variant of the chalice with an enameled nodus came a few years later (1940).

54 - Illustrations in: Werkklassenheft A. Wendung, 1930. The cornerstone depicted on the cover of A. Brecher (op. cit.) was likely created by Anton Wendung.

55 - Letters to Renger-Patzsch from December 10, 1930; January 22, 1931; March 13, 1931.

56 - St. Jude Thaddeus and St. Joseph by P. Orchal - the latter paradoxically carries a model of St. Corpus Christi in his arm. Regarding the "renewals," cf. Brecher, op. cit., pp. 63 ff., pp. 169 ff., as well as Karl Wimmenauer, A New Altar for Corpus Christi Church?, in: Art and Church, 1981, No. 2, pp. 100. Even in the Schwarz estate, several trial sketches with external figure decoration can be found (Pehnt/Strahl, ill. p. 74). It is possible that a Christ child by Maria Eulenbruch was temporarily used as a nativity figure in St. Corpus Christi. 57 - Cat. ars sacra, Löwen 1958.

Finally, the execution chooses the strictest of forms, a horizontal rectangular cuboid (length 47 meters, width 13 meters, height 21 meters) with slightly gable-shaped narrow sides, with the interior area featuring a completely free altar wall, as well as an upper band of light composed of square windows that are only led down in two rows to the floor in the altar area of the northeastern long wall. The low side chapel (as a confessional and Stations of the Cross chapel) is separated from the main room only by a four-meter-wide pillar that carries the pulpit. The square bell tower, 40 meters high, is placed next to the side nave extended to the sacristy. The narrow iron bridge connecting the tower and the main ship in airy height acts as an ironic reminiscence to the pilgrims' bridge of the Aachen Cathedral. The low parish house extends on the other side of the church. The weekday entrance is located at the lower part of the side nave formed into a forecourt (baptistry); from there, one enters a low zone into the high, bright main room.

The appreciation of the church as a spiritual-religious building was initially conducted less by Schwarz himself than by his interpreters such as Romano Guardini or Hans Karlinger. Terms such as poverty and asceticism, emptiness as divine fullness, silent presence of God, or space for working Christians are already more advanced, strongly interpretative interpretations; Schwarz expressed himself in 1930 still rather formally describing: he wanted to "set a dominant in the disorder," and initially react to the loss of the old architectural iconography with the new forms of the time. The "artistic theme of this church (is) indeed the 'box';" the growing sequence of spaces corresponds to the growth of the idea.

St. Corpus Christi also gained great significance due to its unified furnishings, through which it could be elevated to the rank of a new total work of art. Its basis would again be the common design impulse of the Aachen "building lodge," yet Schwarz appears here as the spiritual leading force that gathers the individual masters around a common concept. As he increasingly refined his designs, some works by employees had to be set aside. Ultimately, Schwarz completely dispensed with monumental painting and the polychromy of the space, limiting himself to the contrast of black marble and light, white plaster (for what is "earth" or "yearns from it"). The liveliness of the marble with its fine white veins is particularly evident on the pillar of the side nave, where Schwarz has offset the different line structures of the slabs against each other. The free wall behind the tiered altar has always been one of the particularly eagerly discussed places in the church: Already in 1930, Wendung had sketched a strict, monumental figure of Christ for the wall; in the early 1940s, a painted decoration was finally to be implemented, yet to this day this wall—surrounded by interpretations and anecdotes—has been able to maintain its monumental character. Surely Schwarz had this construction in mind when he spoke in 1930 of the new ornamentation of the human body in the empty spaces ("these spaces hope for beautiful people") or confessed in 1936/37: "God is above. The empty space between the table and zenith is his throne."

Only in retrospect does Schwarz engage more closely with the central theme of the "Body of the Lord" ("Corpus Christi") - the corporeal unity of the people and the Lord realized in the church - whereby he represses or brings to a close the obvious thought of a procession or pathway church, seeing it "calm at the achieved goal." Without having explicitly referred to it, he likely connects these thoughts back to his writing "On the Construction of the Church" (1938), especially referencing the "Holy Path of the Fourth Plan." The church, which was rejected by the mayor and church authorities, positively acknowledged by the city's art council but ultimately built without episcopal approval, is still the most coherent structure of the Aachen school despite some inventory losses and additions. This is also due to the communal furnishings: the altar, pulpit, consecration crosses, baptismal font, and the hanging soffits all trace back to Schwarz. Schwippert designed the furniture, later also the organ prospect (1940); altar candelabra, everlasting light, and Easter candleholder come from Fritz Schwerdt, a collaborator of Anton Schickeis, as does the first chalice with the rock crystal nodus; Anton Schickel himself designed the square rock crystal monstrance, his student Hubert Dohmen the thurible and a ciborium (the latter according to designs by Schwarz); the processional cross was crafted by Wilhelm Giesbert, the liturgical vestments by Wilhelm Rupprecht, the church banners by Anton Wendung. Wilhelm Rupprecht also created a large-scale embroidered Stations of the Cross for the side nave (as well as a Marian image) from 1930 to 1936. The small enameled standing cross on the altar, which had originally still been a pure metal box, was covered by Schwerdt only in the 1950s; the ivory corpus was created by Minkenberg pupil Walter Ditsch. The altar cross was entirely sufficient for Rudolf Schwarz as a "designation of the space."

One of the major, unexecuted projects remained Wendung's lightly colored, geometric stained glass window designs, which developed a serial grid ornament from horizontal rectangular shapes. However, in the end, Schwarz opted for windows made of simple industrial glass. Even regarding the photographs by Albert Renger-Patzsch, which he highly valued and recognized as particularly important for the presentation of his architecture, Schwarz did not refrain from conveying his specific wishes and corrections regarding motif and viewpoint to his master colleague.

The fundamental renouncement of plastic ornamentation was already abandoned in 1931 with the establishment of two wooden, colorfully framed saint figures. Their stylized pathos asserts itself no more in the strictness of the space than the inevitably decorative ingredients of the most recent time, among which the new celebrant altar erected after the demolition of the old communion rail stands out particularly. As a monument in the working-class suburb Rothe Erde, the building remained groundbreaking for all modern architects. Even in 1957, Hermann Bauer confessed: "In last nakedness, architecture stood here, the shell of a space, composed with perfect measure, serving the primal element of light guidance to the cult and the sense of God's house."

Notes:

42 - Cf. Pehnt/Strohl, pp. 70ff., WVZ No. 12; Britta Giebeler, Sacred Total Works of Art, Weimar 1996, pp. 159ff.

43 - This results in a height increase from the parish house over the church to the tower. In 1936, Hanns Schwippert extended the parish house wing but transformed the original, lined window band into a block-like window arrangement. The small entrance door with a windbreak on the southwest side of the side nave has now disappeared.

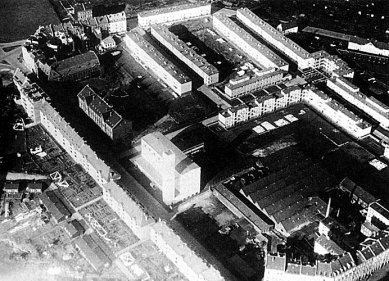

44 - Cf. R.S., Corpus Christi Church, in: Die Schildgenossen, 11, 1931, No. 3, pp. 284f. An aerial photo already shows the shift towards an urban regularity in the settlement "Im Panne-schopp," which emerged shortly after St. Corpus Christi. 45 H. Schwippert strongly opposed a planned altar painting by H. Krahforst (May 26, 1941, Bishop's Diocesan Archive Aachen, file St. Corpus Christi, 21). See also A. Brecher (op. cit., Note 52), pp. 90 f. and the illustration of an interim tapestry (loc. cit., p. 84). 46 On the question of a possible theme for a painting on the altar wall, Schwarz ironically responded with a motif from Genesis: "In the beginning, the earth was void and empty." (according to Prof. Steinbach, in: M. Sundermann, op. cit., 1981, p. 119) 47 - Cf. R.S., On the Constitution of a Workshop School, 1930, p. 18.

48 - Quoted R.S., Altar, in: Die Schildgenossen, 16, 1936/37,5. 137.

49 - R.S., Church Building, pp. 16, 20.

50 - Cf. also his schematic drawings from the fourth plan (the Holy Path), p. 78 as well as the juxtaposition of drawing and church in: R.S., Thinking and Building, Heidelberg 1963, pp. 44/45.

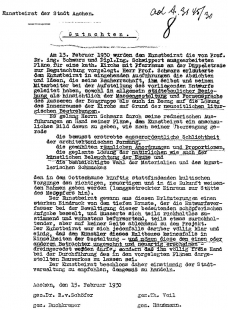

51 - See August Brecher, St. Corpus Christi, Aachen 1997, pp. 15-29. The (perhaps precautionary) advice to forgo submitting a building committee proposal was formally justified by the art council with the church's location in a "not protected area by local statute" (STA, OB Reg. 181). See also Brecher's extensive collection of positive and negative voices on the new building (pp. 30-50). A pamphlet also appeared in the "Westdeutschen Grenzblatt" (predecessor of the "Westdeutschen Beobachters"), No. 58, 1930. Despite the involvement of the structural engineer Prof. Pirlet, the new construction method sometimes led to technical problems: In the first ringing of St. Corpus Christi, the "bridge" collapsed, and during a storm, the roof of the Social Women's School flew away. (Communication M. Getz) 52 - R. Schwarz wanted to use "light not as a lamp, but as brightness, as a luminous space" (Die Schildgenossen, 1931, p. 286).

53 - The chalice "created in agreement with Rudolf Schwarz" (Yearbook for Christian Art, 1957/58, p. 11) was recreated for exhibition purposes after the war (Suermondt-Ludwig Museum, Aachen). A variant of the chalice with an enameled nodus came a few years later (1940).

54 - Illustrations in: Werkklassenheft A. Wendung, 1930. The cornerstone depicted on the cover of A. Brecher (op. cit.) was likely created by Anton Wendung.

55 - Letters to Renger-Patzsch from December 10, 1930; January 22, 1931; March 13, 1931.

56 - St. Jude Thaddeus and St. Joseph by P. Orchal - the latter paradoxically carries a model of St. Corpus Christi in his arm. Regarding the "renewals," cf. Brecher, op. cit., pp. 63 ff., pp. 169 ff., as well as Karl Wimmenauer, A New Altar for Corpus Christi Church?, in: Art and Church, 1981, No. 2, pp. 100. Even in the Schwarz estate, several trial sketches with external figure decoration can be found (Pehnt/Strahl, ill. p. 74). It is possible that a Christ child by Maria Eulenbruch was temporarily used as a nativity figure in St. Corpus Christi. 57 - Cat. ars sacra, Löwen 1958.

Rudolf Schwarz and the History of the Aachen School of Arts and Crafts, Adam C. Oellers (1997)

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment