K+N Residence

|

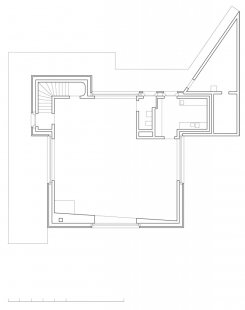

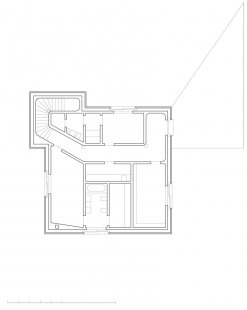

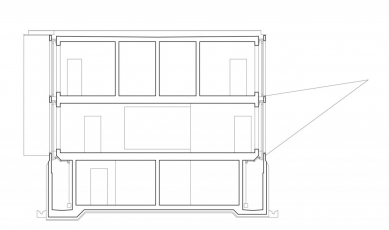

But the living room does not consist solely of walls with large window openings. One corner of the square is occupied by an opaque volume, and the rectangular flight of steps is wrapped around another. Thus the walls do not make a fragile impression like surfaces folded into right angles; rather, the room seems to be part of an organism that constitutes the whole. It is this dimension that gives the building ist strength, its almost excessive impact, and it is from this that everything else ensues. The building is not put together, it is a spatial shell.

Each room, no matter how small, is complete in itself. All the reinforced concrete interior walls are of equal thickness. Furthermore, constructed of the same light-coloured, exposed concrete that gives the building its monochrome unity. The house definitely does not belong to the world of vertebrates, but to the realm of the crustaceans.

The volume and compactness of the building is impressive, as are the atmospheric contrast and lighting effects and the different characters of the main rooms. But the contrasts, far from leading to a fragmentation of the whole, reinforce it and give it the character of a real organism.

0 comments

add comment