Villa JUDr. Eduard Lisky in Silesian Ostrava - Bazaly

Sure! Please provide the text you'd like me to translate.

From July 14 to September 10, 2010, an exhibition titled KAVÁRNA OSTRAVA, showcasing the past and future of the northern Moravian metropolis, took place at the Mánes in Prague as part of the Ostrava in Prague showcase to support Ostrava's candidacy for the European Capital of Culture. The exhibit also presented the villa of JUDr. Eduard Liska, partially compensating for a ten-year-old injustice caused by the removal of the original functional stove brand Brown-Boveri from the Ostrava villa to the then-reconstructed Müller villa in Prague. Following the Tugendhat villa in Brno and the Müller villa in Prague, Liska's villa became only the third national cultural monument representing modern interwar architecture. The villa, embodying the principles of organic functionalism, was built between 1935-36 on the western slope of Slezská Ostrava according to the design of the Šlapeta brothers, Lubomír and Čestmír, and still serves as a residence today. Thanks to the current owners, who bought it in 1970 from the deceased family of Dr. Liska, it has been preserved almost intact, including its interior furnishings. However, the house would benefit from renovation, similar to what has been done at the Loos villa in Prague and is currently underway at Mies' Tugendhat villa in Brno.

I discussed Liska's villa with the person most qualified, Lubomír Šlapeta's son. Professor Vladimír Šlapeta specializes in the history of modern architecture, having taught at several universities (he was the dean at the FA ČVUT in Prague and FA VUT in Brno, and also lectured at TU Berlin, TU Wien, and at universities in Ljubljana and Porto Alegre, Brazil) and is the author of many publications, particularly focused on Czechoslovak interwar functionalism. Vienna professor Jan Tabor characterizes him in his fragment of a glossary on Austrian architecture (see ERA 21 6/09) as: “A long-time star of the Vienna architectural scene, valued as a storyteller of the most beautiful architectural tales from the Eastern Bloc.”

INTERVIEW WITH VLADIMÍR ŠLAPETA

How would you categorize the house in the context of the works of the Šlapeta brothers?

My father always regarded Liska's villa as the most significant building in the area of housing.

How is it possible that JUDr. Liska's villa is only coming into broader public awareness 75 years after its inception?

The concept of aerodynamic and organic architecture represented by this villa was certainly not the main trend in Czech architecture of the 1930s; such an approach was also embraced by Vladimír Grégr in Prague and Bohuslav Fuchs in Brno. Leading architectural magazines avoided publishing villas of this kind, presumably finding them too "bourgeois." Even an architect with the highest social ties, like Vladimír Grégr, managed to publish Dr. Čelakovský's villa in the French review L'architecture d´aujourd'hui, but never in a Czech architectural magazine! Liska's villa was only published in Podešva's review Salon and in the Austrian corporate advertising magazine Heraklith-Rundschau in 1939 and in the publications of art associations in Ostrava and Olomouc. During the German occupation, publicity for such modern architecture was understandably unthinkable. After the February coup in 1948, another problem arose. Because my ancestors opposed the abolition of private design offices as well as the doctrine of socialist realism, they were labeled enemies of the regime. My uncle resisted the then very powerful comrades Vladimír Meduna and Zdeněk Alex in their pressure to modify the design of the Hotel Imperial in Ostrava in the spirit of socialist realism—columns on the façade have no load-bearing function, it is just camouflage!!! My father was dismissed from Palacký University at the beginning of 1949 for his critical stance and was expelled from the Union of Architects in 1958, which practically meant exclusion from the professional community and a ban on practicing until his death; he was even prohibited from working through the Architectural Service of the Fund for Fine Arts. The name Šlapeta or any of their buildings were not allowed to appear in architectural magazines at all. This erasure of the name was passed on to the next generation; even my name was erased from Czech architectural magazines until the late 1970s, and my teachers advised me to change my name. Therefore, Liska's villa remained unknown for a long time. Only in the fall of 1978 did the editorial office of the magazine Umění a řemesla have the courage to publish this building for the first time after almost 40 years. I published the villa in Finland in 1981 in the yearbook of the Museum of Finnish Architecture Abacus 2/1980 in an article about organic architecture in Central Europe, and in 1988 in the magazine Werk, Bauen und Wohnen in Switzerland. However, it was not published in a Czech architectural magazine until 2003!

An evident inspiration for Liska's villa is Scharoun's Baensch villa; does the house stand up to a European, if not a global scale?

I think so. Besides the experience with the project of the villa of Felix Baensche (Lubomír Šlapeta was involved in its execution project - note by the editor), I might also mention the inspiration from the building of Tyrolean architect Loise Welzenbacher. He built a villa for the Heyrovský family on the slope in Thumersbach near Zell am See in 1932, featuring a spiral floor plan. My father and uncle knew this villa from the book Ferienhäuser, published shortly thereafter, which they had in their professional library. Liska's villa is an example of organic functionalism. The initiator of this movement was Hugo Häring, who from the early 1920s attempted to develop a functionalism that would express individual functions through shape and dimensions. For example, hallways in his designs expanded and narrowed according to the density of traffic; individual spaces were understood and conceived as organs of a larger organism, which the building constituted. This concept was presented in his proposal for an organically conceived villa at a time when he shared a studio with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who was simultaneously designing his brick villa in 1923, so two entirely opposing concepts of modern architecture were actually emerging in one room. In the spirit of this concept, Häring soon managed to build a dairy barn in Garkau near Lübeck. These ideas were taken over and later further developed by Hans Scharoun, and organic functionalism peaked in his post-war buildings, including the girls' gymnasium in Lünen, the Berlin Philharmonic, the State Library, and the theater in Wolfsburg.

Could you specify the concept of Liska's villa further?

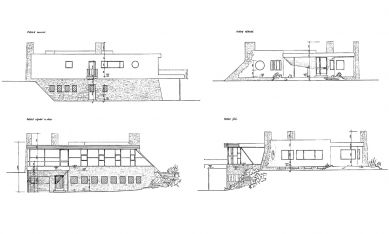

Liska's villa certainly derives from these inspirational sources, but it also does not deny its "Šlapeta-like" character. The stone base part embedded in the slope is anchored in the terrain by three pillars—two on the northern side and one on the southern side. Above this base with the main entrance and garage entrance is organized the residential floor. The layout of the residential floor spreads symbolically from the northern wall like a river delta. Towards the east is the private area with bedrooms and a covered terrace facing the garden. In the middle of the house is the hall with a single-armed staircase from the main entrance in the base with sliding walls allowing for separation or connection of the private and social parts of the house as needed. The western part of the layout consists of a spacious area with a dining nook oriented towards an open terrace above the entrance and a social space with a lowered level and a sofa, which is open via a rounded glass wall to the view of the panorama of the industrial city. The glass wall is topped with a sloped winter garden, whose slope follows the shape of the southern stone pillar anchoring the house into the sloped terrain. Around this pillar winds an alpina, as part of the ornamental garden designed by the well-known garden architect Josef Vaněk from Chrudim. The villa had several interesting technical details. It was equipped with hot-air heating, adjustable for individual rooms. The kitchen had a serving window into the living space. Rainwater collected from the flat roof, which was cared for by Mrs. Lisková for irrigating the tended garden, was directed to a reservoir with a capacity of about 7 m³ located at the bottom of the garden, from which it was pumped to two hydrants in the lower and upper parts of the property.

Considering the extensive western glazing and unique, albeit outdated hot-air heating, is the house—especially the social part—habitable even in winter?

The generous glazing of the gently rounded wall of the living space is, of course, the main idea of the architectural design, therefore it must be preserved, even if it will be technically complicated and future solutions for new heating technology will need to be found. By the way, hot-air heating required 60-70 q of quality coke per season.

Could you tell more about the circumstances surrounding the creation of the house and any other events associated with it?

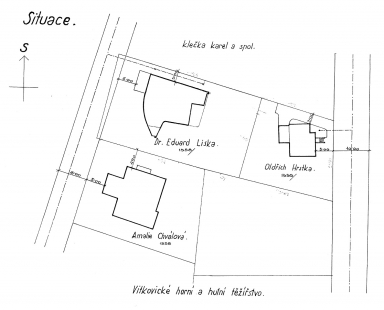

As early as 1932, my father drafted a sketch for the family house of Mrs. Chvalová in Slezská Ostrava. This proposal first included the conical projection of the winter garden, which was later realized in the villa of Karel Urbánek on Bukovanského Street. Mrs. Chvalová ultimately did not accept the proposal and built according to more or less a builder's project, coincidentally in the vicinity of the parcel that Mr. JUDr. Liska purchased. When Mr. JUDr. Liska approached the office of the Šlapeta brothers, they were already well aware of the situation of his plot. Mr. JUDr. Eduard Liska came from the Brno region and moved to Moravian Ostrava after being appointed notary in 1934. He was familiar with the work of the Šlapeta brothers from exhibitions of the Moravian-Silesian Group of Visual Artists at the House of Art. Soon, he acquired a beautiful plot in Slezská Ostrava, and the execution project was dated March 15, 1935. This was relatively shortly after Lubomír Šlapeta's return from his internship with Hans Scharoun in Berlin, from which he returned in mid-October 1934. However, JUDr. Liska still sought to purchase another part of the plot towards the north, to today’s stadium at Bazaly, as the purchased plot was relatively narrow due to the proximity of Mrs. Chvalová's house. However, the purchase of the additional land failed due to its exorbitant price. This circumstance likely delayed construction. Simultaneously, a house for Oldřich Hrstka was also built nearby, designed by the same architects in January 1936. Hrstka's house was a variant of a standard smaller family house that the Šlapeta architects often used since the early 1930s—such as the double house of Konečný-Sieglová in Místek in 1931, the family house of Krystýnek in Rožnov in 1931-32, the family house of Chumchal in Valašské Meziříčí in 1934, and the villa of JUDr. Klimeš in Opava in 1936, the family house of Holý in Řevnice near Prague in 1938, and the family house of Kadlecová in Slezská Ostrava—all share the same or very similar floor plan. Both houses, Liska's villa and Hrstka's house, were built by contractor Ladislav Hendrych, who was a classmate of the Šlapeta architects from the Brno State Industrial School. The rough construction was completed on August 21, 1936, and the entire building was finished in the fall. The price was around 270,000 crowns—the official salary at that time was 1,200 crowns per month. Liska's villa experienced another fateful moment. On the morning of August 29, 1944, an air raid alarm was declared over Ostrava. As recalled by the builder's son, a strong western wind likely shifted the sign by which planes were supposed to orient themselves for bombing, from the east to the west, causing bombs to fall on residential houses. This was presumably noticed by the commander of the allied air fleet intervention, who ordered the last bombs to be dropped on the unbuilt land of Bazaly. One bomb, however, exploded just 8 meters from the left front pillar of the garden. The powerful explosion shattered all the windows of the main façade and many doors, including in the kitchen, some were blown out with their frames. During the war, the façade was provisionally boarded up with planks and cardboard, and was newly glazed and repaired only in 1946. However, the heating was not interrupted.

The villa in Slezská is often compared to the Müller villa in Prague and the Tugendhat villa in Brno, which are now museums. How do you perceive the fact that the house is still inhabited?

It is better for a house to be lived in than to be empty; in such cases, houses quickly deteriorate. The fact that the owner opened the house to the public for guided tours in the summer (tours with expert commentary by architectural historian Martin Strakoš and architecture professor Vladimír Šlapeta took place on Saturday, August 21 and 28, 2010 - note by the editor) is commendable; it surely helped promote this building and modern architecture in general.

Will the stove that was relocated to the kitchen of the Loos villa ever return to Liska's villa, possibly in connection with a future renovation?

That is somewhat of a "pious lie." I am actually one of the youngest of those who visited Mrs. Milada Müller in the 1960s, and I recall that the stove in the villa was of much older type and a more conservative design. The one in Liska's villa was at least 6 years younger and significantly more modern. This is also a property rights issue. The Brown-Boveri stove was purchased from the owners of Liska's villa during the renovation of Müller’s villa in 2000 by the investor of the renovation, which means the city of Prague.

Thank you for the interview.

The editorial team thanks the Association for Ostrava Culture - SPOK for their organizational assistance in creating this contribution, and also thanks Antonín Dvořák (SPOK) and Boris Renner (Ostravaci.cz) for providing photographs, and Professor Vladimír Šlapeta for providing materials from his private archive.

I discussed Liska's villa with the person most qualified, Lubomír Šlapeta's son. Professor Vladimír Šlapeta specializes in the history of modern architecture, having taught at several universities (he was the dean at the FA ČVUT in Prague and FA VUT in Brno, and also lectured at TU Berlin, TU Wien, and at universities in Ljubljana and Porto Alegre, Brazil) and is the author of many publications, particularly focused on Czechoslovak interwar functionalism. Vienna professor Jan Tabor characterizes him in his fragment of a glossary on Austrian architecture (see ERA 21 6/09) as: “A long-time star of the Vienna architectural scene, valued as a storyteller of the most beautiful architectural tales from the Eastern Bloc.”

INTERVIEW WITH VLADIMÍR ŠLAPETA

How would you categorize the house in the context of the works of the Šlapeta brothers?

My father always regarded Liska's villa as the most significant building in the area of housing.

How is it possible that JUDr. Liska's villa is only coming into broader public awareness 75 years after its inception?

The concept of aerodynamic and organic architecture represented by this villa was certainly not the main trend in Czech architecture of the 1930s; such an approach was also embraced by Vladimír Grégr in Prague and Bohuslav Fuchs in Brno. Leading architectural magazines avoided publishing villas of this kind, presumably finding them too "bourgeois." Even an architect with the highest social ties, like Vladimír Grégr, managed to publish Dr. Čelakovský's villa in the French review L'architecture d´aujourd'hui, but never in a Czech architectural magazine! Liska's villa was only published in Podešva's review Salon and in the Austrian corporate advertising magazine Heraklith-Rundschau in 1939 and in the publications of art associations in Ostrava and Olomouc. During the German occupation, publicity for such modern architecture was understandably unthinkable. After the February coup in 1948, another problem arose. Because my ancestors opposed the abolition of private design offices as well as the doctrine of socialist realism, they were labeled enemies of the regime. My uncle resisted the then very powerful comrades Vladimír Meduna and Zdeněk Alex in their pressure to modify the design of the Hotel Imperial in Ostrava in the spirit of socialist realism—columns on the façade have no load-bearing function, it is just camouflage!!! My father was dismissed from Palacký University at the beginning of 1949 for his critical stance and was expelled from the Union of Architects in 1958, which practically meant exclusion from the professional community and a ban on practicing until his death; he was even prohibited from working through the Architectural Service of the Fund for Fine Arts. The name Šlapeta or any of their buildings were not allowed to appear in architectural magazines at all. This erasure of the name was passed on to the next generation; even my name was erased from Czech architectural magazines until the late 1970s, and my teachers advised me to change my name. Therefore, Liska's villa remained unknown for a long time. Only in the fall of 1978 did the editorial office of the magazine Umění a řemesla have the courage to publish this building for the first time after almost 40 years. I published the villa in Finland in 1981 in the yearbook of the Museum of Finnish Architecture Abacus 2/1980 in an article about organic architecture in Central Europe, and in 1988 in the magazine Werk, Bauen und Wohnen in Switzerland. However, it was not published in a Czech architectural magazine until 2003!

An evident inspiration for Liska's villa is Scharoun's Baensch villa; does the house stand up to a European, if not a global scale?

I think so. Besides the experience with the project of the villa of Felix Baensche (Lubomír Šlapeta was involved in its execution project - note by the editor), I might also mention the inspiration from the building of Tyrolean architect Loise Welzenbacher. He built a villa for the Heyrovský family on the slope in Thumersbach near Zell am See in 1932, featuring a spiral floor plan. My father and uncle knew this villa from the book Ferienhäuser, published shortly thereafter, which they had in their professional library. Liska's villa is an example of organic functionalism. The initiator of this movement was Hugo Häring, who from the early 1920s attempted to develop a functionalism that would express individual functions through shape and dimensions. For example, hallways in his designs expanded and narrowed according to the density of traffic; individual spaces were understood and conceived as organs of a larger organism, which the building constituted. This concept was presented in his proposal for an organically conceived villa at a time when he shared a studio with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who was simultaneously designing his brick villa in 1923, so two entirely opposing concepts of modern architecture were actually emerging in one room. In the spirit of this concept, Häring soon managed to build a dairy barn in Garkau near Lübeck. These ideas were taken over and later further developed by Hans Scharoun, and organic functionalism peaked in his post-war buildings, including the girls' gymnasium in Lünen, the Berlin Philharmonic, the State Library, and the theater in Wolfsburg.

Could you specify the concept of Liska's villa further?

Liska's villa certainly derives from these inspirational sources, but it also does not deny its "Šlapeta-like" character. The stone base part embedded in the slope is anchored in the terrain by three pillars—two on the northern side and one on the southern side. Above this base with the main entrance and garage entrance is organized the residential floor. The layout of the residential floor spreads symbolically from the northern wall like a river delta. Towards the east is the private area with bedrooms and a covered terrace facing the garden. In the middle of the house is the hall with a single-armed staircase from the main entrance in the base with sliding walls allowing for separation or connection of the private and social parts of the house as needed. The western part of the layout consists of a spacious area with a dining nook oriented towards an open terrace above the entrance and a social space with a lowered level and a sofa, which is open via a rounded glass wall to the view of the panorama of the industrial city. The glass wall is topped with a sloped winter garden, whose slope follows the shape of the southern stone pillar anchoring the house into the sloped terrain. Around this pillar winds an alpina, as part of the ornamental garden designed by the well-known garden architect Josef Vaněk from Chrudim. The villa had several interesting technical details. It was equipped with hot-air heating, adjustable for individual rooms. The kitchen had a serving window into the living space. Rainwater collected from the flat roof, which was cared for by Mrs. Lisková for irrigating the tended garden, was directed to a reservoir with a capacity of about 7 m³ located at the bottom of the garden, from which it was pumped to two hydrants in the lower and upper parts of the property.

Considering the extensive western glazing and unique, albeit outdated hot-air heating, is the house—especially the social part—habitable even in winter?

The generous glazing of the gently rounded wall of the living space is, of course, the main idea of the architectural design, therefore it must be preserved, even if it will be technically complicated and future solutions for new heating technology will need to be found. By the way, hot-air heating required 60-70 q of quality coke per season.

Could you tell more about the circumstances surrounding the creation of the house and any other events associated with it?

As early as 1932, my father drafted a sketch for the family house of Mrs. Chvalová in Slezská Ostrava. This proposal first included the conical projection of the winter garden, which was later realized in the villa of Karel Urbánek on Bukovanského Street. Mrs. Chvalová ultimately did not accept the proposal and built according to more or less a builder's project, coincidentally in the vicinity of the parcel that Mr. JUDr. Liska purchased. When Mr. JUDr. Liska approached the office of the Šlapeta brothers, they were already well aware of the situation of his plot. Mr. JUDr. Eduard Liska came from the Brno region and moved to Moravian Ostrava after being appointed notary in 1934. He was familiar with the work of the Šlapeta brothers from exhibitions of the Moravian-Silesian Group of Visual Artists at the House of Art. Soon, he acquired a beautiful plot in Slezská Ostrava, and the execution project was dated March 15, 1935. This was relatively shortly after Lubomír Šlapeta's return from his internship with Hans Scharoun in Berlin, from which he returned in mid-October 1934. However, JUDr. Liska still sought to purchase another part of the plot towards the north, to today’s stadium at Bazaly, as the purchased plot was relatively narrow due to the proximity of Mrs. Chvalová's house. However, the purchase of the additional land failed due to its exorbitant price. This circumstance likely delayed construction. Simultaneously, a house for Oldřich Hrstka was also built nearby, designed by the same architects in January 1936. Hrstka's house was a variant of a standard smaller family house that the Šlapeta architects often used since the early 1930s—such as the double house of Konečný-Sieglová in Místek in 1931, the family house of Krystýnek in Rožnov in 1931-32, the family house of Chumchal in Valašské Meziříčí in 1934, and the villa of JUDr. Klimeš in Opava in 1936, the family house of Holý in Řevnice near Prague in 1938, and the family house of Kadlecová in Slezská Ostrava—all share the same or very similar floor plan. Both houses, Liska's villa and Hrstka's house, were built by contractor Ladislav Hendrych, who was a classmate of the Šlapeta architects from the Brno State Industrial School. The rough construction was completed on August 21, 1936, and the entire building was finished in the fall. The price was around 270,000 crowns—the official salary at that time was 1,200 crowns per month. Liska's villa experienced another fateful moment. On the morning of August 29, 1944, an air raid alarm was declared over Ostrava. As recalled by the builder's son, a strong western wind likely shifted the sign by which planes were supposed to orient themselves for bombing, from the east to the west, causing bombs to fall on residential houses. This was presumably noticed by the commander of the allied air fleet intervention, who ordered the last bombs to be dropped on the unbuilt land of Bazaly. One bomb, however, exploded just 8 meters from the left front pillar of the garden. The powerful explosion shattered all the windows of the main façade and many doors, including in the kitchen, some were blown out with their frames. During the war, the façade was provisionally boarded up with planks and cardboard, and was newly glazed and repaired only in 1946. However, the heating was not interrupted.

The villa in Slezská is often compared to the Müller villa in Prague and the Tugendhat villa in Brno, which are now museums. How do you perceive the fact that the house is still inhabited?

It is better for a house to be lived in than to be empty; in such cases, houses quickly deteriorate. The fact that the owner opened the house to the public for guided tours in the summer (tours with expert commentary by architectural historian Martin Strakoš and architecture professor Vladimír Šlapeta took place on Saturday, August 21 and 28, 2010 - note by the editor) is commendable; it surely helped promote this building and modern architecture in general.

Will the stove that was relocated to the kitchen of the Loos villa ever return to Liska's villa, possibly in connection with a future renovation?

That is somewhat of a "pious lie." I am actually one of the youngest of those who visited Mrs. Milada Müller in the 1960s, and I recall that the stove in the villa was of much older type and a more conservative design. The one in Liska's villa was at least 6 years younger and significantly more modern. This is also a property rights issue. The Brown-Boveri stove was purchased from the owners of Liska's villa during the renovation of Müller’s villa in 2000 by the investor of the renovation, which means the city of Prague.

Thank you for the interview.

The editorial team thanks the Association for Ostrava Culture - SPOK for their organizational assistance in creating this contribution, and also thanks Antonín Dvořák (SPOK) and Boris Renner (Ostravaci.cz) for providing photographs, and Professor Vladimír Šlapeta for providing materials from his private archive.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment