Interwar Exhibitions of Contemporary Housing

Causes of emergence and contemporary response

|

The Deutscher Werkbund brought together, since its establishment in 1907, the best representatives from the fields of art, industry, crafts, and commerce with the aim of finding the best modern solutions. It could also be characterized as a departure from the arts & crafts movement. In 1918, it sponsored the Neues Bauen movement, whose architectural theory it gradually adopted during the 1920s and presented at several regular exhibitions, including the successful Die Form in the summer of 1924 and primarily Die Wohnung in the Weissenhof colony in 1927.

Weissenhof

The Die Wohnung exhibition was basically a response to the housing crisis that accompanied the post-war economic crisis. As early as February 1920, a wing of the Werkbund was created called the Württembergische Arbeitsgemeinschaft (which published in 1924 and 1926 the memoranda Die Wohnung der Neuzeit, dealing with economically efficient housing); however, discussions about actual Werkbund assistance in solving the housing crisis began in 1925 when, based on a promise of financial support from the Stuttgart fund for public housing, it was decided that an exhibition on the theme of Housing would be held in Stuttgart. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter C. Behrendt immediately began working on the preparation of the site plan for the exhibition colony with 100 apartments. The exhibition was to take place in 1926, but later the date was postponed by a year, and the program was refined, which said that there would only be 60 apartments in the Weissenhof colony. Mies's construction plan was presented to the public in 1926, approved by the Werkbund and ultimately by the Stuttgart city hall, and Mies was charged with managing the entire project. There was a debate about the architects who should participate in the design of individual houses, which ultimately resulted in a list of 17 names. These were mostly then still little-known architects who were members of the Deutsche Werkbund, Zehnerring, or Novembergruppe. Most of the specific proposals were presented on the occasion of the official opening of the Bauhaus in Dessau.

Ultimately, 33 houses were created in the colony with 63 apartments. The buildings were characterized by an effort to utilize new building materials to enhance the efficiency of potential mass production of similar objects. Nevertheless, they retained great diversity. Individual authors designed houses according to the conditions set by Mies (who mostly determined the construction program, developed the description of the "typical" client, and set costs), although some authors (e.g., J. J. P. Oud and M. Stam) managed to implement quite significant changes.

|

|

Construction of individual houses began on March 1, 1927, and in April, interior architects began working on the individual apartments. The exhibition opened on July 23, 1927. Visitors could view the furnishings and technical equipment of modern buildings, models of realized European and American buildings (more than 60 architects were represented, including El Lissitzky, Wright, Mendelsohn, etc.), while the houses themselves were partly unfinished, thus showcasing contemporary construction techniques, and, of course, the finished houses were the highlights. Work on the unfinished buildings continued until September 1, and the exhibition ultimately ended on October 31, 1927. However, the first tenants could only move into the houses after February 17, 1928.

The attendance was very successful in terms of visitor numbers – 500,000 people. However, the responses were not particularly flattering. The Public Exhibition Council itself stated in its assessment on October 29, 1927, that the main goal of providing financially accessible housing was not achieved. Mies was criticized for giving “his” architects too much freedom; thus, the architects paid little attention to standardization, which could also have been caused by the unsatisfactory sloping plot.

Most tenants refused to move into apartments furnished with the original furniture and complained after a year about humidity, lack of storage space, etc.

The two main representatives of the then-recognized "Stuttgart School," Paul Bonatz and Paul Schmitthenner, who drew more from the principles of traditionalism, subjected the Werkbund exhibition to significant criticism. They attacked Mies for his proposal for the site plan, which supposedly stemmed more from artistic than technical needs. Schmitthenner came up with an alternative proposal for the Kochenhofsiedlung colony as early as 1927, which was realized in 1933. Local architects here designed traditional wooden constructions with a strong nationalist undertone, ultimately, the project's significance did not exceed the regional boundaries.

|

The objects remained in a state of disrepair long after the war. Their designation as monuments in 1956 did not help; partial repairs occurred only in 1968 on the occasion of the Bauhaus exhibition opening, in 1977 celebrations for the 50th anniversary of the Weissenhof took place, and the Freunde der Weissenhofsiedlung e.V. foundation was established, and finally from 1981 to 1987, all 11 remaining houses were carefully restored. In 1987, a major exhibition was held to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the colony's construction. In 2002, the museum was relocated from the ground floor of Mies's row house to Le Corbusier's duplex.

Brno Colony New House

|

It was a private initiative by builders František Uherka and Čeňek Ruller, however, it was also supported by the then Union of Czech Works (thus it is mentioned as one of the Werkbund exhibitions). The colony under Wilson's Forest in Žabovřesky was opened to the public in September 1928, during the time when a large Exhibition of Contemporary Culture was taking place at a nearby exhibition ground.

Unlike the Stuttgart colony, local architects exclusively presented their concepts of individual family houses here (only Josef Štěpánek was an architect from Prague). The authors were not overly limited by initial conditions - they derived solely from the parcel layout, which had been previously developed by Bohuslav Fuchs and Jaroslav Grunt, the prescribed building height, and the requirement for an economical layout.

Ultimately, only B. Fuchs, J. Grunt, and Jan Víšek adhered to the last requirement. These three authors came up with concepts of economical row houses, where Fuchs's proposal could also foresee future serial construction. Víšek's puristic design stood out with a uniquely solved layout, however, it was already structurally more expensive due to the solution of the last recessed floor.

The other authors - Hugo Foltýn and Miroslav Putna (who designed a duplex that looked almost Le Corbusier-esque with ribbon windows), Jiří Kroha, Ernst Wiesner, Jaroslav Syřiště, and Josef Štěpánek - mostly designed detached family houses, however, they focused primarily on showcasing new construction and material possibilities.

The departure of most authors from the requirement for an economical layout meant that the exhibition, similar to Weissenhof, did not fulfill one of its main objectives, yet it was primarily a significant manifestation of functionalism. No houses from the exhibition were sold.

Most houses were later reconstructed during the communist era, often very insensitively.

Other Exhibitions of Contemporary Housing in Europe

|

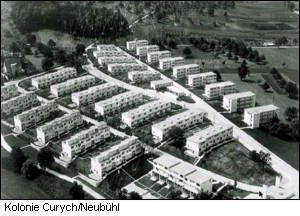

After exhibitions in Linz (1929), Stockholm (1930), and Eglisee in Basel (1930), another large Werkbund exhibition, Neubühl, was held in Zurich. It is the most extensive Werkbund housing estate - 105 family houses with three to six rooms and 90 apartments (35-118 m2). The estate was planned collectively (architects M. E. Haefeli, Hubacher & Steiger, W. M. Moser, F. Roth, and Artaria & Schmidt), thus maintaining a uniform architectural character.

|

In 1933, this period concluded with an exhibition colony in Milan. However, the last significant exhibition colony is generally considered to be the one that opened a month after the end of the Vienna exhibition in 1932 - the Baba colony in Prague.

Baba Colony in Prague

|

In 1920, the Union of Czechoslovak Works was established, which participated in the exhibition in Monza and Paris, where it presented a Czech response to the international style. Its activities at that time were associated with publishing the magazines Výtvarná práce and Výtvarné snahy. In 1928, the Union supported the New House colony and exhibited the house of Josef Havlíček at the Exhibition of Contemporary Culture.

Already at the end of 1928, when the New House exhibition ended, a decision was made to build a settlement of the Union of Czechoslovak Works in Prague.

By that time, there was already one plan for a similar colony of typified modern family houses in Prague - Jaroslav Frágner designed it in 1927 for the builder Václav Havel. In Barrandov, a Czech Hollywood was to be created - a quarter for filmmakers. However, Havel rejected Frágner's concept of three typified functionalist villas, and in 1929 handed the commission to architects M. Urban and V. Grégro, but ultimately only two villas were built.

|

The entire project begins during the peak of the global economic crisis, which certainly manifested itself in Czechoslovakia as well. After the 1920s, when modern architecture increasingly succeeded to the displeasure of the then leftist leader Karel Teige, to the extent that it was criticized by Teige as "bourgeois state modernity," attention began to shift increasingly towards social housing, which could help solve the housing crisis. In this context, there was consideration for individually detached and row minimal houses in the planned Baba colony.

Until this point, a parallel can be traced between the Baba and Weissenhof colonies. While in Stuttgart (and similarly in Brno), the houses are not designed for specific builders, and the departure from the original theme of the exhibition - affordable housing - can perhaps genuinely be attributed to Mies, who gave the architects too much freedom; in Prague, the houses are designed for specific builders - all members of the Union of Czechoslovak Works. And those, in the case of Baba, are primarily from among artists, entrepreneurs, professors, i.e., wealthier classes, who understandably do not yearn for minimal typified houses. Thus, although a competition for the minimal house was announced in December 1929, no minimal house appears in the model of the settlement from January 1930. Builders and proposals changed continuously until 1931, when the final designs were bought by the Union of Czechoslovak Works, a month later the regulatory plan was approved, and from April 25 to September 7, 1932, 20 houses were built. In 1933-1940, a whole series of additional villas were also built.

On September 7, 1932, the exhibition was opened. The interest was enormous, 12,000 people attended the ceremonial opening. The autumn exhibition had to be extended by a month.

Similar to Weissenhof, many young architects had the opportunity to realize their designs here. All the architects were local - with one exception, Dutchman Mart Stam, who also had his realization in Stuttgart and here created a very subtle constructivist Palička Villa.

|

All villas open their living parts to the south - towards the Vltava River - and are functionalist, but we can find functionalism in different forms here.

On the one hand, there is the classic functionalism of Gočár (4 villas). The author of the site plan, Pavel Janák, designed his own villa with a studio, in which we can find traces of Loos's raumplan or the division of spaces according to Le Corbusier, similarly as in one of the five houses of František Kerhart. Oldřich Starý designed two studio houses, one for the famous graphic artist and designer Ladislav Sutnar. Evžen Linhart at the house of editor Lisý departs from the classic two-wing layout, similarly as the authors of several other houses built after 1932 (e.g., Kerhart's house Bělehrádek).

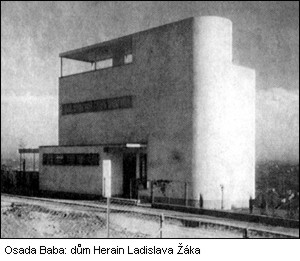

However, the most famous houses in the colony are strictly two-winged, built according to the designs of the young and then nascent architect Ladislav Žák. This originally a painting student infused dynamic elements into rectangular functionalism. He often worked with contrasting sharp and rounded shapes. In designing, he uses maritime forms - prominent horizontality, rounded shapes, superstructures, etc. (for which he is later criticized by architect Losenický, who called it formal fetishism). He also drew inspiration from ship cabins in his layouts - while the ground floor of his house always contains a generously designed living space with direct access to the terrace, the upper floor features a narrow hallway and several very small bedrooms - cabins - serving only for sleeping or as a refuge for someone who wants to be alone. It is essentially a kind of smaller collective houses, where residents spend most of the day together and only move to their privacy at night; by the way, Žák dealt with the theme of the collective house throughout his life, although he ultimately did not manage to realize any. The Zaorálek house features a terrace on the upper floor, accessible only from the bathroom. A cylinder of stairs protrudes from the rectangular volume of the Herain house, which adds to the terrace roof. Similarly, we find a covered roof terrace at the Čeněk house.

|

The Union of Czechoslovak Works concluded its activity with the construction of an exhibition house on Národní třída in Prague in 1936. In the decade between Munich and the infamous year 1948, it again used the name Union of Czech Works, after which it was incorporated into the Central Office of Folk and Artistic Creation.

The era was not kind to the colony itself. Several residents had to leave the settlement even before the war, after February 1948, the houses were converted into multi-generational homes, and several residents emigrated even after 1968. Many houses were more or less remodeled, with some being insensitively appended with garages; however, to this day, the colony has been preserved in quite good condition. There are even houses that have survived without significant alterations.

We can only evaluate the fundamental significance of these exhibitions in retrospect after several decades. Today it sounds almost unbelievable that a set of extraordinarily high-quality and diverse buildings was created within a short time, often designed by emerging architects. This primarily testifies to the standing of the Werkbund at that time. It is interesting to observe how, particularly in the case of Stuttgart's Weissenhof, architects did not respond to current problems and assignments, but utilized this opportunity to verify their own theories (the clearest case probably being Le Corbusier and Stam). Therefore, it is no surprise that almost all colonies, despite achieving great visitor acclaim, sparked considerable criticism in professional circles, which we now view more as a discussion between two ideological currents, supported by interesting theoretical and practical arguments.

Today, three-quarters of a century after their emergence, we can still view these often already distorted sets of buildings as absolutely unique examples of the best of their time, and many ideas implemented here remain inspiring for the current generation of architects.

It raises the question of what a professional union that a city administration would grant relatively free rein and financial resources, as was the case with Weissenhof, might look like today? What might the realized works look like, and would young architects, who might not prove sufficient experience, but on the contrary, unconventional thinking, also stand a chance?

|

Stephan Templ

Regular price 380 CZK, our price 350 CZK

A publication about the Prague settlement Baba, which was built between 1928 and 1932 in Dejvice. It presents individual houses and their owners - personalities of the cultural and social life of the 1st Republic. The book includes an introductory study, a catalog of 34 houses, biographies of architects, data about builders, a bibliography, and indices.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment