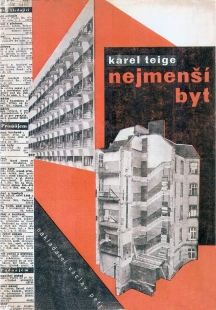

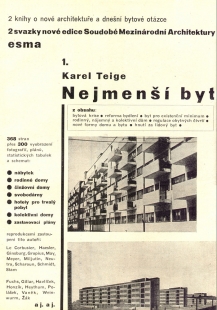

Karel Teige: Apartment for Existential Minimum

Cheap popular apartments are currently at the forefront of modern architecture's interest. Yet, statistics on uncovered housing needs, enumerating how many families and individuals live without adequate, health-safe apartments, how many people reside in overcrowded flats or in buildings marked for demolition, unable to afford a decent place given their incomes, show that the issue of popular housing remains unresolved on a wide social scale. International congresses on modern architecture have repeatedly emphasized that the question of housing for the impoverished classes, for the so-called existential minimum, is more or less deficit in all civilized countries, and that housing scarcity is indeed a shadow over our civilization. This issue is unresolved in terms of material, technical, organizational, financial, as well as programmatic and architectural aspects. Just as a century ago for hundreds of thousands of workers immigrating from the countryside, which the burgeoning large-scale industry concentrated in cities and industrial areas, today for the vast majority of the population living at the level of existential minimum, there are hardly any apartments in our cities. These classes are relegated to unhealthy and barely sufficient accommodations, to rented rooms, to inadequate lodging, and often live in spaces that are hard to call an apartment. If they manage to obtain a reasonably decent apartment in a newer building, the rent constitutes an disproportionately high percentage of their income. The demand for elementary housing culture: to provide every person with a separate, albeit small, living space, thus a private room, whose minimum area according to sanitary norms is 8 m² and 20 m³, is today an unattainable dream of housing welfare when reality, expressed by statistics, teaches us that in an enormous number of cases more people live in apartments than there are beds.

Our new buildings and construction methods are too expensive. The gap is widening between the price of a house (and subsequently the demanded rent) on one side and the wages and incomes of the existential minimum classes on the other. If rent is not to exceed 15-20% of the tenants' income, today the layers of existential minimum can hardly aspire to housing in new buildings. They cannot afford higher rents, as the remainder of their monthly income would then not be enough for food, clothing, and basic cultural needs. The housing market is saturated today. There are quite a few vacant apartments, yet the layers of existential minimum suffer from a housing crisis. The lack of apartments is relative. It is not a shortage of apartments, but of those accessible to broad popular layers. This lack could be remedied not by creating new apartments, but only by organizing housing allocations and continually improving accommodations and their furnishings in older buildings.

Contemporary architecture initially addressed the issue of popular housing with the construction of family houses, which were scaled-down and simplified versions of villas. The spaces were so small that they were hardly livable, and the houses stood on tiny lots, so in such garden colonies, there was greater spatial crampedness than in small apartment buildings with multiple stories. It has become evident that the architectural form of smaller living units must be sought not in the form of houses, but in large multi-story apartment complexes. Old apartment buildings in enclosed street blocks with internal courtyards and courtyard wings, with apartments oriented regardless of sunlight, are indeed repulsive storages for people, a product of unbridled land and rental speculation that sought to exploit every square meter of space at the expense of the most basic housing hygiene requirements. Against such unacceptable and outdated construction methods, which still dominate today, the new architecture advocates for so-called row construction, namely the removal of encroached blocks and the construction of houses in parallel rows, where the distance between the rows of houses is greater than the height of the houses, ensuring that apartments receive sufficient sunlight, and the open space between the house rows can be transformed into public gardens. Each house has enough air and light. Only then can the living area be reduced without health detriments, so that the volume and consequently the construction costs of the rent lower when large windows opening into light, airy space eliminate the feeling of interior crampedness. Row construction corresponds best to houses of the so-called arcade type. The floor plan of an arcade house or a house with a side corridor resembles the floor plan of a rapid train carriage. Just as there are compartments accessible from a side corridor, so here one enters from such an arcade or corridor into the apartments, whereby the hallway and amenities have windows overlooking the arcade or into a well-lit and ventilated corridor, and the living rooms have windows on the opposite facade. Cross ventilation is thus ensured.

If such an apartment is to be affordable, we must drastically simplify and reduce the amenities. The kitchen is limited to the smallest area, possibly to a single piece of furniture that combines a sideboard with a work surface, sink, and gas stove, or a small stove is alongside. A bathroom is still an unattainable luxury for affordable apartments. It must be replaced by a shower and a washbasin next to the toilet, with water drainage in the floor. Living spaces, however small, should have large windows (and, if possible, a balcony) accessible to air and sunlight. To ensure they are bright, they will also be painted in light colors. If the apartment consists of a single space, it is advisable to divide it with drapery or furniture arrangement into a day area and a sleeping area. A more correct arrangement that better corresponds to the living style of working intelligence is one where the living space is divided into two as separate rooms as much as possible, such as living quarters for men and women. Census and housing statistics show that the number of individuals living outside of families and households is increasing. We must think of a new type of apartment for single individuals. Either we need single-person housing units, or we need to reserve entire floors in buildings for tenants who do not have a household. Their apartments would resemble small hotel rooms lined up next to each other, just like compartments in a rapid train carriage. A bed, a table, two chairs, a bookshelf, and a washbasin would be all the furnishings of such cabins. A supplement to an apartment without a kitchen are public dining rooms.

The furnishing of a popular apartment is as simple as possible. As few pieces of furniture as possible. Only those that are absolutely necessary. Every unnecessary piece of furniture robs space, which is already limited, and restricts movement within the apartment. The dimensions of the furniture must correspond to the dimensions of the small apartment, and thus also be as small as possible. Space-saving requires the use of folding and collapsible furniture. Folding or collapsible beds, instead of a table, folding surfaces; a library with a folding surface replaces a writing desk, and a sofa bed provides two pieces of furniture in one. Soft furniture in good carpenter and lacquer workmanship is just as suitable as furniture made of hardwood and is cheaper.

Even the most economically executed new constructions do not have apartments cheap enough to be accessible to the least wealthy, and so the layers of existential minimum are forced to live in old houses and furnish their apartments with inherited furniture. In old houses, there are no ideal and safe small apartments. Nevertheless, such apartments can be made more livable by certain adaptations and reasonable arrangements of furniture. Even old furniture can serve well. Bourgeois furniture from the turn of the century is unnecessary for a small apartment. It is too cumbersome and large. But furniture from our grandmothers' era has dimensions that correspond to human scale and does not take up much space. Common, unpretentious furniture, the product of generalized Biedermeier styles, can still be useful today; it can be modernized with a small touch-up and repairs: with a saw and plane, which remove unnecessary decorations that collect dust, and a brush that gives the furniture a cheerful, bright color.

The main condition in an apartment furnished with new or old furniture is: to exclude all practically unnecessary pieces of furniture, to remove foolish ornaments, to give the apartment bright colors, and not to obscure the windows with heavy curtains. As much free space as possible; wall surfaces in a single color, undivided ornaments, textiles made of washable materials, and also without ornaments.

Such an arrangement of an apartment and its furniture is an aid. It is an improvement we can implement if we have at least a decent apartment and furniture. It is medicine that, however, does not cure the disease of housing insufficiency nor does it make old houses flawless and universally suitable residences.

Our new buildings and construction methods are too expensive. The gap is widening between the price of a house (and subsequently the demanded rent) on one side and the wages and incomes of the existential minimum classes on the other. If rent is not to exceed 15-20% of the tenants' income, today the layers of existential minimum can hardly aspire to housing in new buildings. They cannot afford higher rents, as the remainder of their monthly income would then not be enough for food, clothing, and basic cultural needs. The housing market is saturated today. There are quite a few vacant apartments, yet the layers of existential minimum suffer from a housing crisis. The lack of apartments is relative. It is not a shortage of apartments, but of those accessible to broad popular layers. This lack could be remedied not by creating new apartments, but only by organizing housing allocations and continually improving accommodations and their furnishings in older buildings.

Contemporary architecture initially addressed the issue of popular housing with the construction of family houses, which were scaled-down and simplified versions of villas. The spaces were so small that they were hardly livable, and the houses stood on tiny lots, so in such garden colonies, there was greater spatial crampedness than in small apartment buildings with multiple stories. It has become evident that the architectural form of smaller living units must be sought not in the form of houses, but in large multi-story apartment complexes. Old apartment buildings in enclosed street blocks with internal courtyards and courtyard wings, with apartments oriented regardless of sunlight, are indeed repulsive storages for people, a product of unbridled land and rental speculation that sought to exploit every square meter of space at the expense of the most basic housing hygiene requirements. Against such unacceptable and outdated construction methods, which still dominate today, the new architecture advocates for so-called row construction, namely the removal of encroached blocks and the construction of houses in parallel rows, where the distance between the rows of houses is greater than the height of the houses, ensuring that apartments receive sufficient sunlight, and the open space between the house rows can be transformed into public gardens. Each house has enough air and light. Only then can the living area be reduced without health detriments, so that the volume and consequently the construction costs of the rent lower when large windows opening into light, airy space eliminate the feeling of interior crampedness. Row construction corresponds best to houses of the so-called arcade type. The floor plan of an arcade house or a house with a side corridor resembles the floor plan of a rapid train carriage. Just as there are compartments accessible from a side corridor, so here one enters from such an arcade or corridor into the apartments, whereby the hallway and amenities have windows overlooking the arcade or into a well-lit and ventilated corridor, and the living rooms have windows on the opposite facade. Cross ventilation is thus ensured.

If such an apartment is to be affordable, we must drastically simplify and reduce the amenities. The kitchen is limited to the smallest area, possibly to a single piece of furniture that combines a sideboard with a work surface, sink, and gas stove, or a small stove is alongside. A bathroom is still an unattainable luxury for affordable apartments. It must be replaced by a shower and a washbasin next to the toilet, with water drainage in the floor. Living spaces, however small, should have large windows (and, if possible, a balcony) accessible to air and sunlight. To ensure they are bright, they will also be painted in light colors. If the apartment consists of a single space, it is advisable to divide it with drapery or furniture arrangement into a day area and a sleeping area. A more correct arrangement that better corresponds to the living style of working intelligence is one where the living space is divided into two as separate rooms as much as possible, such as living quarters for men and women. Census and housing statistics show that the number of individuals living outside of families and households is increasing. We must think of a new type of apartment for single individuals. Either we need single-person housing units, or we need to reserve entire floors in buildings for tenants who do not have a household. Their apartments would resemble small hotel rooms lined up next to each other, just like compartments in a rapid train carriage. A bed, a table, two chairs, a bookshelf, and a washbasin would be all the furnishings of such cabins. A supplement to an apartment without a kitchen are public dining rooms.

The furnishing of a popular apartment is as simple as possible. As few pieces of furniture as possible. Only those that are absolutely necessary. Every unnecessary piece of furniture robs space, which is already limited, and restricts movement within the apartment. The dimensions of the furniture must correspond to the dimensions of the small apartment, and thus also be as small as possible. Space-saving requires the use of folding and collapsible furniture. Folding or collapsible beds, instead of a table, folding surfaces; a library with a folding surface replaces a writing desk, and a sofa bed provides two pieces of furniture in one. Soft furniture in good carpenter and lacquer workmanship is just as suitable as furniture made of hardwood and is cheaper.

Even the most economically executed new constructions do not have apartments cheap enough to be accessible to the least wealthy, and so the layers of existential minimum are forced to live in old houses and furnish their apartments with inherited furniture. In old houses, there are no ideal and safe small apartments. Nevertheless, such apartments can be made more livable by certain adaptations and reasonable arrangements of furniture. Even old furniture can serve well. Bourgeois furniture from the turn of the century is unnecessary for a small apartment. It is too cumbersome and large. But furniture from our grandmothers' era has dimensions that correspond to human scale and does not take up much space. Common, unpretentious furniture, the product of generalized Biedermeier styles, can still be useful today; it can be modernized with a small touch-up and repairs: with a saw and plane, which remove unnecessary decorations that collect dust, and a brush that gives the furniture a cheerful, bright color.

The main condition in an apartment furnished with new or old furniture is: to exclude all practically unnecessary pieces of furniture, to remove foolish ornaments, to give the apartment bright colors, and not to obscure the windows with heavy curtains. As much free space as possible; wall surfaces in a single color, undivided ornaments, textiles made of washable materials, and also without ornaments.

Such an arrangement of an apartment and its furniture is an aid. It is an improvement we can implement if we have at least a decent apartment and furniture. It is medicine that, however, does not cure the disease of housing insufficiency nor does it make old houses flawless and universally suitable residences.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

3 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

rok?

Ondřej Bartůšek

24.03.07 02:19

přimlouvám se

Jiří Bláha

24.03.07 11:38

Still in progress

Jan Kratochvíl

24.03.07 01:28

show all comments