The office M1 Architekti, whose distinctive style is defined primarily by three partners Jakub Havlas, Jan Hájek, and Pavel Joba, was established in 2000. Although they are more of a small design office, where in addition to them, there are usually three to five other architects working as needed, it turns out that even with this relatively small number they are capable of “leading and executing two to three fairly large projects and thus managing contracts with an investment value around one billion”. The office M1 Architekti, whose distinctive style is defined primarily by three partners Jakub Havlas, Jan Hájek, and Pavel Joba, was established in 2000. Although they are more of a small design office, where in addition to them, there are usually three to five other architects working as needed, it turns out that even with this relatively small number they are capable of “leading and executing two to three fairly large projects and thus managing contracts with an investment value around one billion”.In this interview, we have decided to overlook the recent significant experience of reconstructing the Czech National House on Manhattan in New York (2004 – 2008) and focus primarily on questions that revive the often neglected truth that architecture is not design and must respect broader urban relationships. Against the backdrop of the city, we thus addressed the new building of the Faculty of Science in Olomouc (2004 – 2009) as well as the yet-to-be-realized project of the Janáček Cultural Center in Brno (1st place in the competition, 2003 – 2004).

The new building of the Faculty of Science in Olomouc has been operational for a year now, having opened on October 1st, at the beginning of this academic year. Have you received any feedback on its operation yet?

Jan Hájek: Not yet. There are still steps being resolved that were not completed on time; for example, the furnishings were not tendered. However, we do not have any references regarding its operation yet. One could also say: no news is good news. But we do have feedback on technical execution, where various technical problems have arisen: for instance, there is leakage in the roof or the fume hoods in the laboratories are not functioning...

Can you indicate how you work in a team during the design process? For example, who had the inspiration for the building at the very beginning? Pavel Joba: The project began with an architectural competition in 2002 - 2003. We all work together on competitions; everyone tries sketching solutions and then we agree on the best one. It can't be said that one person invented the building from the beginning. It's a team effort. After construction began, we of course delegated one person, in this case, Honza Hájek, to avoid sending five architects unnecessarily to Olomouc. He then handled all the coordination aspects. However, we created the design as a team. J. H.: The question of who designs what arises sometimes. But I can never clearly answer it personally. Perhaps it is this unclear definability that shows the team aspect. P. J.: The best answer is probably the fact that even after work, we go out for fun together. We are not partners joined by random success. On the contrary, we are friends who have known each other from school for a long time, spent a lot of time together, and conversely had no work. In the beginning, we only knew that neither of us wanted to work in a big project management firm. And that we wanted to make it on our own.

Both of you laugh... P. J.: We got a task right after school to design a loft addition for the film producer Tomáš Krejčí in Malá Strana. We met a great person then, but nothing was actually realized – not even the loft. But we had a lot of fun. He partly didn't even pay us, but the experience brought us closer together (laughs). And shortly after that, right after school, in the summer of 2000, we participated in a competition for a funeral hall in Opava, in which we completely failed. A total fiasco. And aside from the failures, what was your first joint realization? J. H.: I have a bad memory... P. J.: I don't know either... It’s interesting how you remember the details of your first unassigned works, while the completed ones did not stick in your mind so sharply... J. H.: Probably the Havlíčkovy sady... Oh no! That's just my old man's forgetfulness. Our first realization was the reconstruction of the embassy in Algiers. By a stroke of luck, we won the contract at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It was a job, both in size and location, that no one else seemed to be very interested in. Originally, they were supposed to tear down two partitions and shift another two. Moreover, Algiers at that time represented a highly dangerous area on the brink of civil war. Only on site did we find out the actual condition of the building; the work was postponed and the assignment expanded. Algiers was our first presentable realization. The first commission on which we operated systematically as an office.

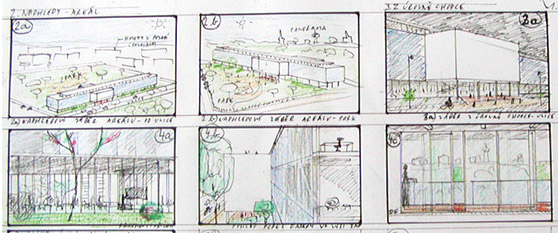

When we return to Olomouc, can the concept of the building be captured in words? For example, in the context of broader relationships... J. H.: As one gradually refines the theme, it seems to me that building cities becomes increasingly important. To not harm – with what we are working on today – for example, the work of Camillo Sitte, who created the concept of city expansion. He founded the new Olomouc exceedingly well with a visionary approach and defended the old one against demolition. In my opinion, architecture should not be some cherry on top or an exhibition. I would be satisfied if the house were perceived as ordinary architectural production, yet designed by someone who knows how a city should look. That is exactly what contemporary architecture and urban building lack: either there are star architects or there are ruthless planners of vast areas. Those who work without any humanitarian education, without an effort to discover anything about the history of the area. The building itself is thus part of Sitte's green ring that partially surrounds the historic core of Olomouc. Here Sitte placed solitaires, and only after this zone did he deploy the street skeleton of the new city. And everything else follows from that. The building is designed to stand out from the plastered gray block structures as well as from the surrounding panel housing, and above all, to read as a solitaire in accordance with Sitte's opinion. Interestingly, we only realized afterwards that Sitte himself designed what he called the Olomouc block for these areas – a prism that is 200 meters long and about 18 meters wide.

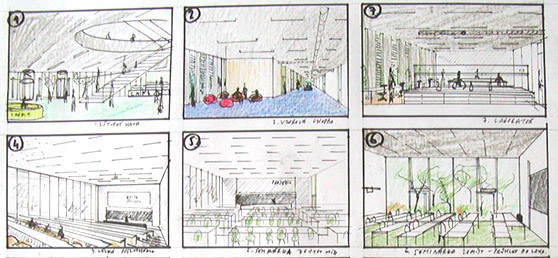

J. H.: 209 x 18. Naturally (laughs). So we worked within the realm of Sitte's view... And you really came to this realization afterwards? And can we return to the term Olomouc block? J. H.: Later on. The term is mentioned, I believe, in the preface to Sitte's book City Building According to Artistic Principles. Here, among other things, the form that Sitte defined in the regulatory plan for the newly proposed area is described. It was to be a block of houses devoid of – perhaps for better hygiene – courtyards. In our instance, he arrived at the noted dimension of 200 x 18 meters. I don't know if he further divided this volume into individual apartment buildings, but the essential aspect is the dimension of the mass. Thus, this discovery undoubtedly meant confirmation of your concept. J. H.: One always feels uncertainty. If one honestly thinks about things, one's thoughts really emerge from that uncertainty. This discovery undoubtedly confirmed for us that the given dimension is correct for the site. The assignment was already questioned; many said it was oversized for the location. We felt that way too, and therefore we tried to minimize the building's volume. If you look at the results of the architectural competition, among the forty proposals, you will find volumes from 150 to 200 thousand cubic meters. Our design ended up at 90 thousand. Did the fields located within the building influence its form? P. J.: The building is relatively neutral. It does not appear too playful like a school. It shaped itself in a way as an institution. However, scientific fields like physics, chemistry, or mathematics are somehow palpable in it. Perhaps precisely due to a certain impersonal nature. J. H.: I believe that the fields do not directly appear in the concept. But they assert themselves technically, in the laboratory equipment and so forth. Rather than thinking of it like a school, we conceived the building as an institution significant to the city. Moreover, this is also why we happily entered the competition – in urbanism, this institution is a good fit in this location. It transcends the significance of a school. It is a modern type of university where education is not separated from research and development. And simultaneously a building crucial for the city – the Palacký University serves about a third of the population in Olomouc and has around thirty thousand students today. The internal spaces are formed like a school. For instance, the central corridor, which we designed, perhaps subconsciously, to be over-dimensioned – five meters wide. With some columns, a faint reference to Greek stoas. It is these spaces, unlike an ordinary administrative building that wouldn’t need them, that allow for gathering and the social life of students.

Although the Olomouc faculty is a linear structure with a spine in the form of a central communication axis, we tried to make the corridor feel more like a hall. J. H.: As for the expression of the school, I actually don't know what it should look like. We might know classical schools or Gillar's functionalist school with large glass surfaces... But at the same time, we are familiar with the description of a school from Renaissance literature – in the section on decoration of buildings, it is stated that the pride of the school is books and instruments. The treatise further states that the school must stand in a remote place, preferably in a park, to provide silence and peace for thinking and that its inner riches and decoration should be precisely the books. There is nothing in the text about decorating facades or about form. P. J.: Nevertheless, there are examples that one, if not ignorant, must respect. For example, the construction of Austro-Hungarian school buildings reached a certain level of perfection. The buildings have beautifully legible entrances, or rather at that time they usually had two entrances: one for boys and one for girls. We, of course, made one clearly legible entrance. However, Austro-Hungarian examples still hold validity. Schools from that time function remarkably well in terms of sustainable development. They have high ceilings, well-managed proportions between windows and wall sections, so that they do not need air conditioning in the summer nor excessive heating in the winter. Even though they are often double flats, which is quite a luxurious space, they still function well to this day. To ensure that the building, due to its linearity of two hundred meters, was not so uneconomical, we had to choose a three-flat layout for energy efficiency in Olomouc. But we learned from the well-lit corridors of Austro-Hungarian schools and tried to bring in light indirectly through the rooms. J. H.: We certainly perceive values such as spatial and light generosity, which we abstracted from Austro-Hungarian examples. P. J.: And ultimately the desire for moral and, after all, physical long-term durability... The building is stripped of ambitions to shock but has in it the desire to age gracefully.

In the case of Olomouc, there is sometimes a lament about the lack of quality modern architecture. Did you realize this deficit in, for example, the expert debate that you must have gone through in the city? J. H.: I don’t think so. I don't know if it’s still Sitte’s influence, but only in hindsight did we realize how well the urban development department had processed the urban plan. This was actually the reason for holding the architectural competition. Problems arose when we learned how complicated the investor, Palacký University, is. However, the quality of the urban plan’s processing is absolutely crucial: I can imagine cities that would, in the same location, build a car showroom... P. J.: From the city's side, we felt no obstacles. The fact that one person acts as the guarantor for the investor, who may or may not have taste, is a different matter. We encountered more of a human factor where material solutions were dictated to us – and not from the institution but one nominated representative from the school. Could one individual truly change your project? P. J.: Not conceptually, but materially... For example, certainly in the interior. J. H.: But I’d rather focus on the overall city context. We were surprised by how easily this building was negotiated in the administrative procedures. Perhaps it was also because the house was so large that it exceeded the vision of those involved in the process. At the moment an individual looks at things through a narrow perspective, they can perceive buildings only as individual entities. And if they look at such a large building without distance, they have no opinion at that moment. I definitely advocate the placement of this program at the given location as well as the volume of the building. As Švácha writes, if the house were smaller, it would not be able to stabilize the area or oppose the surrounding communist urbanism.

P. J.: At this point, we are in the phase of zoning proceedings, and an application for the issuance of a zoning permit has been submitted. The most important thing, of course, is for the city to secure funding. Currently, increasingly detailed materials are being prepared. The process will become irreversible once the state contributes a subsidy. Otherwise, the project will probably not materialize. However, I believe the state should contribute; this is not a project of regional scope. There is practically no quality concert hall in the country. Neither the Rudolfinum nor the Smetana Hall suffice. The process is now so complex that it is getting difficult to navigate it. You are gradually making certain changes to the design... P. J.: The project was submitted to the architectural competition for a gap that was smaller than the originally requested volume, which could reasonably fit into the given location. We welcomed the fact that after the competition, calculations were made in 2004, and it clearly showed that the amount of 1.8 billion could not be accounted for. The city declares 190 million... Thus, the small hall, which we considered an error from the beginning, was removed from the program. Next door is the Besední dům, where you will find a hall for 500 people. This reduction was also related to the fact that an expert acoustic firm was invited to the competition, which advocates the use of so-called acoustic chambers. However, these would expand the building by eight to ten meters. We accepted all program reductions with relief. J. H.: What was taken from the volume of the Philharmonic was added to public space. The work is not just about the new construction of the Philharmonic itself, but about a space that unites the Pražák Palace, the Besední dům, the International Hotel, and the hotel annex. It is thus a kind of equivalent to New York’s Lincoln Center with a free space uniting several institutions.

P. J.: Most recently at Gogol Bordello... Otherwise, an important figure from our scene for me is the poet and radical Xavier Baumaxa. And of course Horkýže slíže – no need to comment on that. J. H.: The last time I was actually at a party on the houseboat Bukanýr, which we organized with colleagues from Projektil, Michal Fišer and Petr Uhlík ... where Juraj Sonlajtner played, and our third partner Kuba Havlas was on drums. We play football and hockey together in a similar setup. Does your mentioned architectural band have a name? J. H.: Zero. No, actually ZORE! Sorry. (laughs) And your relationship with music? J. H.: I like Saint Etienne and Culture Club, for example. When we participated in the reconstruction of the Czech House in New York, I had the chance to see The Marriage of Figaro at the Metropolitan Opera, where Magdalena Kožená made her New York premiere in the role of Cherubino. And I admit it was one of my strongest experiences of singing in my life... A complete success. I was surprised by how little was written about this event in our country. When Helena Vondráčková or Karel Gott sing for compatriots in America, everyone knows about it. But that someone is truly representing us at the highest level... P. J.: From this area, my strongest experience recently was the new production of Rusalka at the National Theatre. In the direction of Jiří Heřman, it was a modern performance on a world level. I believe that identification with music is extremely important today. A hundred years ago, practically no reproduced music was listened to. Today, this identification perhaps holds more weight than the older one: Tell me what you read... J. H.: I would like to counter that. I have no musical ear, so I am often much more influenced by books. I even catch myself behaving or even speaking and using certain expressions based on what I am currently reading. Recently, I read a lot of books by Haruki Murakami, and at the moment I perceive reality as a collage of parallel worlds.

P. J.: We always try to approach from the whole to the detail. We try to compress the building so that it does not occupy more space on the ground than necessary. Almost always, in the overall relationships, we try to balance the building with some outdoor forecourt. So that next to the filled area, built volume, there is also an empty one. The relationship between fullness and emptiness is extremely important to us. This theme ultimately emerges in every task. As we move further, to the building itself, it may happen that our buildings seem too ordinary to someone. The more we discuss architecture, we clarify that we do not want to build like world stars. Our goal is to create buildings that will stay here and may not even be noticed at first glance. First and foremost, they should not harm. The buildings we aim for can also serve as workers. Apartment buildings. Personally, I think a lot about a residential building in Vinohrady. In my opinion, it still represents an unsurpassed type of structure. The houses did not need HVAC or air conditioning; their proportions between windows and solid wall sections were perfectly solved. J. H.: And they were built in such a way that all of them together made sense. They formed streets, squares, courtyards, and yards... For us, it is essential to know what purpose the house serves within the overall organism of the city. We consider it a victory when we can place a house – which may look inconspicuous – into a location in such a way as to co-create a new comprehensible space. We do not want to deceive ourselves that we are creating something super new in terms of design. That we are stars. On the contrary, I think we are just connecting to something that has already been here and was lost in some historical epoch: awareness of what a city should look like. The term “star architecture” – including the relevant criticism of this phenomenon so characteristic of today’s times – was introduced, or at least made visible, by Kenneth Frampton. Recently, I heard a metaphor by which contemporary cities behave as if they were collecting modern architecture. They want to have their Herzog and de Meuron, they would like Zaha Hadid, and they still lack Calatrava... The method of collecting, however, is usually far from thoughtfully building a city as an aesthetically and functionally managed whole. Excluding examples from the Netherlands, where self-governance is capable of organizing a well-staffed competition for a master plan and then, still based on its blueprint, to divide individual houses amongst excellent architects through another competition, this tactic speaks more of management aimed at enhancing the image in tourism... J. H.: Luigi Snozzi aptly named the issue, who held a lecture in Prague. He spoke about how each historical era had a method of directing ordinary construction production, which constitutes 99 percent of cities. Each era knew it. It is visible in the projects of all historical world architects: although they did not have the chance to build an entire city, their work also included notions of how a city should look. Alberti built only a few churches or palaces, but nevertheless, in his work, you can find ideas about the city as a whole. However, today architects have retreated a lot – into interiors, into design... And we are trying to do the opposite – to address the issue from a much greater distance. It is nothing new; it speaks to values that were established at the beginning of our culture by Greek and Roman architecture, through the architecturization of open space. Alberti defines things by stating that it is what is right and not what we are capable of. Thank you for the interview. Kateřina Lopatová

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

2 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Pěkně jste to řekli.

Petr Lešek

07.03.10 04:05

opravdu hnusné

Jana K.

07.03.10 09:32

show all comments

|

1.jpg)