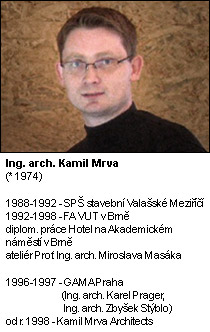

Interview with Kamil Mrva

|

In addition to working on his own projects, Kamil Mrva is involved in the operation of the Ostrava Center for New Architecture and dedicates time to architecture or industrial design students, having participated in organizing several student workshops.

THE PATH TO ARCHITECTURE

Since I was a child, I enjoyed drawing and was fascinated by various buildings, not just houses but also bridges and structures. I grew up in Kopřivnice, where there is a technical high school, but coincidentally, when I was preparing to enter high school, my parents told me that I could draw well and suggested I try a construction school instead. They also believed it would be better for me to go to construction school in Valašské Meziříčí than to the mechanical engineering school in Kopřivnice, because we have family in America, which could have posed a political problem and might have prevented me from attending school.

I became interested in construction at the technical secondary school. I liked the craft itself and even considered becoming a bricklayer. We had a great teacher for fine arts, Mr. Ing. Palát, and architecture was taught by Mr. Architect Žert, who, along with Architect Kalivoda, was highly respected in the region. Later, I tried to apply to architecture school, and I succeeded. I was extremely fortunate that this happened after 1989; otherwise, I probably wouldn’t have been able to attend university due to political reasons.

You got admitted to the faculty of architecture in Brno. During your studies, you traveled a lot. How did this traveling and what you saw influence you afterwards?

It was after 1989 when architecture was just beginning to be reshaped in our country. Suddenly architects had the opportunity to design and travel again. Traveling is very important for our profession; it's necessary to see what is new and how it works.

As I mentioned, we have family in Canada and the USA, which allowed me to visit during my studies. I was quite disappointed that in our contemporary architecture classes, we only discussed architects like Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe, while Frank Lloyd Wright was only mentioned in one lecture. At that time, my studio instructor was Mr. Architect Kyselka, and when he found out I was planning to spend three months in America, he told me I must see Fallingwater House and other buildings by Wright. So, I planned a month-long trip to see his works, which proved very beneficial. Above all, I realized how Wright managed to work with materials in nature.

Further travels awaited me with Professor Masák. It was quite serendipitous. I completed a year-long internship at the GAMA studio in Prague, after which I began studying at the Prague school. Unfortunately, they wouldn’t recognize some subjects I had completed at the Brno school and sent me back to the third year. At the last moment, I transferred back to Brno and enrolled with Professor Masák, who, fortunately for me, still had an open spot. At that time, the diploma took three semesters, and in the second semester, we took a study trip to the Netherlands. There were eight of us in the studio, and each of us was responsible for planning the program for one day of the trip. I was tasked with introducing others to the works of Wiel Arets. Interestingly, when we arrived at his own house, Arets was mowing the lawn. During the trip, Professor Masák guided us on what to focus on for our diploma project. For us, the Netherlands was a new experience, and I am still amazed at how things can function so smoothly there.

At the same time, you worked as a sculpture restorer during your studies. How did you get into that?

I studied for three semesters under Professor Kyselka, and one summer he called me to see if I wanted a summer job with sculptor Vavruša. It was still uncommon back then for students to have summer jobs, so I was glad. Initially, we worked on the balustrade around the baroque fountain Parnas in the Zelné trhu in Brno. I later assisted him during the school weekends, and a beautiful friendship developed.

Restoration work is, of course, something very different from architecture. We used to travel to restore sculptures across southern Moravia. Mr. Vavruša has a license for the restoration of cultural monuments, which always made me marvel at how these sculptures could survive for 300 or 400 years and their role in complementing the overall object. For instance, in Rešice near Dukovany, there is a small chapel with a path lined with sculptures. One realizes that even in such a small village, there may have been commendable people, whether it was the mayor or the priest, who could gather money for something so beautiful.

Practical experience is very important for an architecture student and beginning architect, but I was intrigued that you did not go through many architectural studios. Did you only work in the GAMA studio with architect Karel Prager?

Yes, I only worked in the GAMA studio among larger studios. However, I occasionally helped local designers. After school, I wanted to return to Kopřivnice and sought employment. Unfortunately, I didn't get any interest from studios in the area. So, I decided to try working on my own right after graduating.

So, the fact that you started working independently right after school was more determined by the local situation, or was that your intention?

I really returned from school with the intention of reaching out to someone here and working for them. When that didn’t pan out, I traveled to Canada for a few months again and came back with the mindset that I had nothing to lose and tried to start on my own.

RETURNS TO SCHOOL

Until recently, I taught externally in Brno. I started teaching primarily because of my house and studio in Kopřivnice, which Karel Doležel came to visit and write an article about. He reached out to me with the offer to consider returning to the school. At that time, I thought of three topics that would be suitable for a student's semester project.

I view teaching as a form of gratitude for being able to study architecture in Brno. At the same time, I just wanted to give it a try. I taught industrial design at the local technical school, and it was a benefit for me since I could turn off my mobile phone, thus allowing me a little break from work. When I'm around young people, I can observe how architecture evolves, as students always watch the latest happenings. In practice, there’s less time to follow architectural developments.

Of course, I enjoy teaching. It's not a matter of finances; the travel to and from Brno costs me much more than I earn from teaching.

How do you teach?

In my first year of teaching, I traveled to the school as an external consultant. In the second year, I started leading several students as their project supervisor. I then also supervised diploma and bachelor's students. Together with Karel Doležel, I also lectured on architecture in our region and American architecture.

We organize workshops for the students. For instance, when I prepared several topics related to Kopřivnice, we organized a multi-day workshop, which included several professionals besides our students. Workshops are very important because we know that during the week, students have many other school and extracurricular commitments and activities. During the workshop, however, a student can dedicate two or three days solely to studio work. Usually, we hold it three weeks into the course, and the student comes with their first vision. At the end, they must present what they devised during the workshop. This allows most students to greatly advance in their work, providing them with inspiration for future projects.

What is the role of the school in educating architects? What do you think of the opinions that practical experience is the most important thing for architects?

I believe the school is very important. It is possible to practice architecture without formal education, but there are very few people who can do this well. It may happen that in a year with, say, 60 students, there are 5 students who truly understand what architecture is. For instance, perhaps their parents are architects. However, most students expect the school to teach them.

But practical experience is also important. I completed four years of study, one year of practical experience, and three semesters of my diploma project, which worked very well for me. I have concerns regarding the cancellation of the year-long practical experience at the Brno faculty.

PLACE AND SERVICE

Do you have your own definition of architecture?It is hard to say what architecture is. When I create architecture for someone, the place and listening to the investor is vital for me. The place determines the story, and our work is a service. Of course, an architect must not be forced by anyone into anything. The initial idea must come from the architect, and only then comes the consultation with the investor.

Where do you find inspiration?

In the location, the given environment, and in the first contact with the client.

How do you work?

After the first meeting with the investor, we suggest basic sketches and ideas. Upon their approval, we develop a study and possibly a model, followed by documentation and approvals from authorities. We handle the implementation documentation for smaller projects and some services ourselves; for larger projects, we collaborate with other designers. We perform author supervision. Thus, we work from the beginning all the way to the building approval.

|

Teamwork in our studio is very important. I am responsible for initiating the project. Then my colleagues work on it, and I consult with them, present it to the client, and discuss it with colleagues on site. For larger projects, we assign certain tasks among ourselves, but one person manages the project while I am always involved as well.

How many collaborators do you have?

Currently, we are three architects and two civil engineers. We meet with external collaborators from various professions for discussions.

From what is known about you, it appears that your career has been significantly influenced by your own house. Is that true?

It was very important for me. I wanted to build something myself first and experience the construction process firsthand, in overalls. I was on the construction site daily and drew in the evenings.

At the start, I worked in my parents' apartment and considered renting some space. Perhaps because of my trips to Canada, I held the belief that clients couldn't come to me on the fourth floor of an apartment building. Then my grandfather gifted me a garden, where I could attempt to build something that I could work further in and where clients could come visit me to see what wood, frosted glass, poured floors, and so on looked like.

Interestingly, when a client comes here and sits at the table in the meeting room, they no longer pull out their dream catalog project from their pocket. If they had come to me in the panel apartment, they would have likely shown me what they liked and how they wanted it drawn. This was especially important five years ago; now, clients mostly come to us because they found us through published works, they like what we do, follow us, and eventually contact us.

|

When I designed my house, I also designed two or three other buildings, but they were houses for acquaintances of my acquaintances. However, it was thanks to this house, and especially its subsequent publication, that I reached beyond my circle of friends.

You have designed several family houses that carry a discernible signature. It is evident that you prefer wood as a structural expressive material. What do you base your designs on when creating family houses?

Each house is different. Designing a house is a long-term process, and each house is always tied to a specific environment and the time in which it is created.

We continue to strive for simple shapes, which may also be influenced by the economic situation in this region. People here often come with a specified budget from the outset, and while we consider this a challenge, it helps us in the design process.

Wood is the traditional material here. I have tested it on my house and know what to expect from it. Now I also recommend it to my colleagues. Wood softens the atmosphere. I also like that it is a natural material. However, we are also designing houses without wood now. We like to combine materials; each has its advantages and disadvantages.

What do you think about standard houses? Have you ever tried to design a standard house?

It's certainly one of the possible paths for the future, but I believe that each house should be based on the specific place. It is not possible to create a completely identical house for Brno and Kopřivnice, and that doesn’t even touch on the placement on the lot or orientation to the cardinal directions.

As a student, I tried to design about ten standard homes and thought it could work. However, I ultimately chose an individual path. Assuming a house meets the needs of more clients and locations, it can indeed appear in various places and may be commercially advantageous for the studio.

Coincidentally, we are currently implementing a location with eight family houses in Horní Bečva. Initially, we thought each house would be different. In the end, we were compelled by authorities, as it is a protected landscape area, to have the same roofs, resulting in only two mirror-image house types.

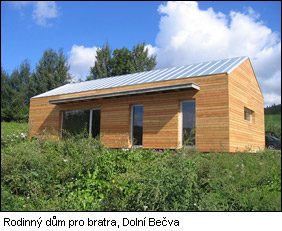

|

It is fundamentally different. Designing a house for my brother was similar to when I was designing my own studio. Of course, the house is based on what works for my brother and his wife. Given that there was a very limited budget, I was also responsible for construction coordination, so similar to my own house, I helped on-site in overalls there as well. If I were designing that house for an outside client, I would only provide author supervision, and the project would be much more expensive.

My family has supported me in my profession from the beginning and allows me relative freedom and trust in my designs. Besides my brother's house, I also designed an optometry office for my mother.

ARCHITECTURE ON THE PERIPHERY

You operate in the Ostrava region, still somewhat on the outskirts of major architectural happenings. Recently, the quality of buildings in this region has risen significantly. How do architects work here?It stems from the situation in all of northern Moravia. When I worked in Prague, I complained to a friend who is an economist about how dire the situation was here. He told me that in ten years, investors would come to Ostrava and the economic situation would improve. And now it's happening. There has been a significant construction boom, which might not be ideal for architecture since there are numerous architects and designers who design somewhat recklessly; however, many quality houses are being built here.

|

They do not avoid it. We currently have one project in Ostrava, where we are working on a proposal for 33 row houses.

What is demand like for contracts in this region?

Demand is currently high. All of my colleagues here are very busy, especially those who work on contracts from start to finish.

In Ostrava, you are involved with the Center for New Architecture. What motivated its establishment?

The Center for New Architecture (CNA) was established as a non-profit association, with founding members Radim Václavík, David Floryk, and myself. Radim and I had long been considering working together, and ultimately we were brought together by CNA. We wanted to give others a chance to discuss architecture and develop educational activities. We strive to somewhat emulate centers like the Architecture Gallery in Brno or Jaroslav Fragner Gallery in Prague, although we do this in our free time.

Is this a project that unites local architects, or is its goal to spread architecture among the public?

We certainly aimed more at promoting architecture in northern Moravia further afield. Which so far has been successful. For instance, we recently held the exhibit Other Houses 007, which is somewhat akin to the exhibition of Austrian architects from the Vorarlberg region, thereby promoting awareness of regional architecture.

Some of your houses are located in the CHKO Beskydy. How is designing in the Beskydy Mountains and particularly dealing with the authorities?

Currently, if an architect designs in the CHKO Beskydy, their project must be positively approved by the Agency for Nature Conservation and Landscape Protection in Rožnov pod Radhoštěm. No building authority will proceed without the agency's approval. Recently, however, acquiring this positive approval has become problematic for us.

What contributes to that? What do they usually find objectionable in your projects?

It is obviously about the people who make decisions. They are not architects or specialists, but follow certain set rules. They would prefer to see log houses with small wooden windows with grids in the CHKO. Clients come to us wanting a low-energy or passive house with glazed surfaces integrated with nature, which is a problem. You can't build a Socratic house in the CHKO; it has to have small windows facing south.

Unfortunately, not everyone is held to the same standards. An architect submits a project to the CHKO, and they begin to draw modifications contrary to copyright. On the other hand, they approve catalog houses with towers, which doesn’t seem to bother them.

Interestingly, sometimes someone writes about us being associated with the CHKO and that we get approvals that others do not. This is not true; it's rather the opposite.

Kopřivnice, where you live and work, has a rich industrial history and also numerous urban and architectural issues stemming from that industrial heritage. Several topics you've worked on with students have involved Kopřivnice. What is the future potential here?

I have always compared Kopřivnice with Zlín. It’s a certain type of zonal city among hills with a central zone, a residential belt, and areas for production and sports. Currently, there are some investments taking place here that Kopřivnice might not need, and the city center is still underdeveloped. However, if I didn’t believe in the potential for the future here, I wouldn’t be here.

THE PRESENT

|

We have a lot of work at the moment. Everything we are working on consists of interesting projects, and we enjoy working on them quite a bit.

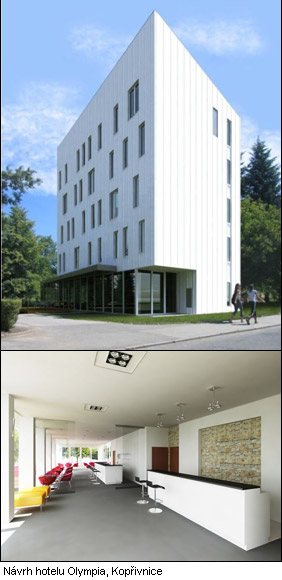

We are designing row houses for Ostrava, and we are realizing a hotel in Kopřivnice. In Rožnov pod Radhoštěm, we are beginning work on the reconstruction of a shopping center, which took three years for us to get approved. There are three family houses under construction, and eight more projects await on the table. Projects are already scattered throughout the republic, and we are also working on the design for a car dealership in Split.

And what about the future?

At this point, we don’t have much time to forecast the future. However, I never say that Kopřivnice is the best place for me.

Thank you for the interview.

Martin Rosa

|

| Kamil Mrva Architects picture |

2007

Our price: 300 CZK (dispatch time: up to 7 days)

|

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

58 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Sídlo na Horní Bečvě

jan Hrstka

23.11.07 08:48

prosím o vysvětlení

Martin Franěk

23.11.07 10:37

prosim

karel kriz

24.11.07 12:41

Ráz krajiny

Pepa Malina

24.11.07 12:24

Odpověď pro pana Kříže

jan Hrstka

24.11.07 01:38

show all comments

Related articles

0

14.11.2024 | Man Who Bet on Houses - Film Premiere

0

24.04.2020 | Silesian Ostrava will modify the area near the Hermanice church according to Kamil Mrva's design

0

23.05.2017 | habilitation lecture of Kamil Mrva at the Faculty of Architecture VUT

0

04.01.2016 | The work of Kamila Mrva at the exhibition in Valašské Meziříčí