|

| M4 in the garden of their studio (from left Milan Jirovec, Miroslav Holubec, Matyáš Sedlák) Miroslav Holubec *1974 Prague; FA ČVUT 1998 Milan Jirovec *1962 Prague; Fsv ČVUT, field of civil engineering, 1985 Matyáš Sedlák *1974 Prague; FA ČVUT 1999 The office m4 architects was established in 2003 by Miroslav Holubec and Matyáš Sedlák, in 2007 they joined forces with Milan Jirovec. |

In the debate with M4, we also deepen the current discussion about the Czech housing estates, which has not escaped the black-and-white optics even twenty years after November. However, this conversation does not only touch on the houses themselves, but also on the social contents. The impacts of the economic crisis have temporarily slowed the outflow of the multilayered structure of the local population; however, the recovery of the economy and construction production will also bring the threat of ghettoization of the housing estate.

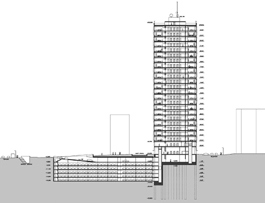

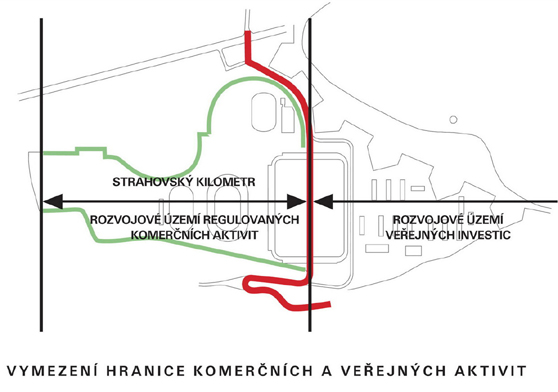

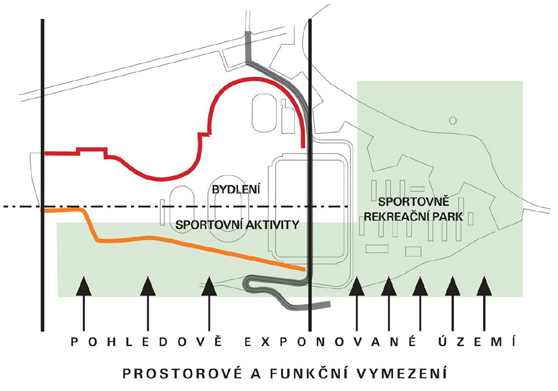

The third discussion topic is the architectural "monument": modern architecture, the purpose of which is to bridge the past, present, and future. Will we demolish the Strahov?