Studio pha led today by Jan Šesták and Marek Deyl is primarily associated by readers of Archiweb with a series of family houses – in Prague's Kyje, Klokočná, Lety near Dobřichovice, Všeradice, Řitka, Černošice or recently in Děčín – but also with several striking interiors: the pilot showroom of Scott, interiors of the ground floor and basement of the Dancing House, the presidential bathroom at Prague Castle, the Senate of the Czech Republic meeting room, the internal staircase of the Institute of Molecular Genetics of the Czech Academy of Sciences or exhibition stands for the firm Lasvit. Studio pha led today by Jan Šesták and Marek Deyl is primarily associated by readers of Archiweb with a series of family houses – in Prague's Kyje, Klokočná, Lety near Dobřichovice, Všeradice, Řitka, Černošice or recently in Děčín – but also with several striking interiors: the pilot showroom of Scott, interiors of the ground floor and basement of the Dancing House, the presidential bathroom at Prague Castle, the Senate of the Czech Republic meeting room, the internal staircase of the Institute of Molecular Genetics of the Czech Academy of Sciences or exhibition stands for the firm Lasvit.However, the scale of projects has recently grown to include apartment buildings. Alongside this interview, we present one of them – a recently completed, distinctly volumetric house on a challenging sloped site along Radlická Street. What defined its form, how many people work in an ideal office, why has the studio practically stopped entering competitions and how to change the public awareness of public space, architecture, or design? You will find out in the following interview. Moreover, with the end of the summer, we will reveal where and why architects go to relax... Both of you studied at UMPRUM, though at different times. Jan Šesták studied architecture, Marek Deyl design, and later during an internship in Berlin, interior design. Are your roles divided similarly in the office? Marek Deyl: We started in Libeň on Gabčíková Street, in a building where two companies were located. After a while, we decided that we needed to separate more and moved here to Prague 1. As for specialization, we function in quite a rare symbiosis. However, Jan has always been the one who has been in the field of architecture longer. For me, who came from school, he was a source of everyday experience. Jan Šesták: The essence is the creation. I find it ideal when two people are involved in it. Three seem too many, and one too few. It's alchemy. We met fifteen years ago when we both independently went to Milan – to the Salone de Mobile fair. I took Marek – who was still a student at the time – into my car. Since then, we have basically not parted ways. Within the office, we really work on everything together, but each has their own project – either in relation to their client or a personal connection to the project. M. D.: We look over each other's shoulders, not because we are spying, but out of love for the topic. We enjoy going to work. We tend to lean towards a family-type office.

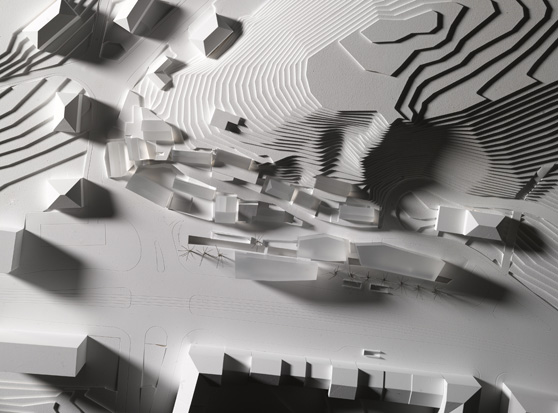

M. D.: The team is changing, but approximately eight. Everyone has their role. Two years ago, for example, we added colleague Honza Škoda, through whom we offer investors supervision services for small villas and houses. We have not yet found a Czech term; it's about "project management – cost management," which has proven to be very effective for us. He is able to organize a tender, close a contract, oversee the construction, organize control days, write reports... Do you offer this service for external buildings as well? M. D.: Exclusively for our own houses. It goes beyond the powers of ordinary construction supervision, for instance, by monitoring prices. As a result, it helps not only the client but also us. PROJECTS What are you currently working on in the office? What do you consider your most significant task at the moment? J. Š.: We are finalizing the documentation for a building permit for the Holečkova apartment building, which was a very complicated plot with many limitations. Not just construction limitations, but also neighborhood ones, and so forth. So we are pleased that the project is being correctly administratively pushed through. Because the phase of designing the house and its architecture is long behind us... Personally, I am also happy that it will actually go ahead. We have completed, for the umpteenth time including the mentioned supervision, an interesting villa in Prague, which unfortunately we cannot present. Finally, the Radlická 142 apartment building for RT Reality has also been completed and inhabited, which is, albeit a standard investor's house, but we managed to maintain several key elements that were in the project from the beginning. It is a very challenging plot: an extreme slope above a retaining wall, which cuts into the noisy Radlická street; the land also rises up the slope and should ideally be fully utilized…

How did you find an architectural solution for such a complicated plot? J. Š.: The resulting mass of the house reflects all the mentioned limitations. We decided to divide the building into three parts: with the existing retaining wall, we decided to retreat into the slope – thus essentially dedicating a piece of the investor's plot to public space, because at this point Radlická Street was practically choked. We decided that in this part, we would treat the house as a retaining wall that continues from ČSOB to the existing school. The first three floors of the building are part of the structure that is the retaining wall. Above it, two floors of offices are placed – in the front part we thus created a mass of four to five floors, which is common in this street, and at the same time a mass that shields the apartments placed higher up the slope. The building also slightly opens towards Radlická, thus the apartments are at least partially deflected from noise and also oriented to the east and west – that is, away from the traffic. The apartments facing south, towards Radlická, are, on the other hand, protected by the office structure and also by relatively deep loggias. The house also includes an atrium where you have no idea about the street noise. It hides a surprisingly intimate space. The broken house, perhaps an aggressive shape, is not our whim. The house is sculpted from the limits of the lot.

M. D.: We have quite a diverse mix of projects in the office. We have been working long-term, for example, for the Lasvit company as well. It turns out that even small projects can have significant importance in the future. When we did our first pilot interior for the Scott representation in 2004, it was not a major project in terms of volume, but nonetheless, on a small footprint, we managed to create something quite striking, which then went through global architectural servers and magazines, and was taught about in schools. We are pleased when our work has an impact in broader spheres. Similarly, a recently realized presentation for the aforementioned Lasvit company in Milan, in the historic Serbelloni Palace. J. Š.: We still nurture the desire to do things well, even to experiment a little. Unfortunately, our country is not large enough in terms of designing large buildings to afford to experiment. Budgets tend to be tight. That is why we favor these small projects, because there experimentation is often still feasible. It is possible to create something striking, unusual, to try something new on it. To captivate a wider public. M. D.: The Czech society is also very conservative in relation to architecture. Can you give an example? M.D.: Whenever a more prominent world architecture could be born here... for example, Kaplický's library. J. Š.: A highly discussed issue. M. D.: But it is an example that symbolizes a feeling that persists here to this day, in my opinion. I grew up with it. Jan actually did too – he interned in France, I interned in Berlin. Contact with the world has always been immensely important to me. It is constantly reaffirmed that the intellectual potential of Czech architects is absolutely comparable to the world; the difference is only in opportunities. Perhaps that's why we invest energy into smaller projects – which includes, apart from the already mentioned works, is currently also the broadcasting studio of Radio Wave. J. Š.: A similar space is offered by the mentioned villa – a private investor tends to be more accommodating. However, there are relatively few state projects in the Czech Republic. Moreover, large architecture faces a small willingness and courage from society and investors to venture into something that is riskier. In the end, it really comes down to money. When you look at the Middle East, to countries subsidized by gushing natural resources and cheap labor, where architects from all over the world gather for large experiments. Which I personally often consider excessive. But that is actually not possible here at all.

And where do you see the reasons for the indicated state? J. Š.: The economy is small. If a multinational company comes here, it will not consider the local branch to be representative enough to be worthy of an experiment. It will set up in Frankfurt or London. The Czech Republic is not a market or location where foreign investors want to be bold. Similarly, neither do Czech investors. M. D.: There are more factors; it is also a historical problem. Social demand, the education of society in the field... After all, we have lagged behind in art by twenty years compared to what was happening in Europe throughout the entire twentieth century. Since 1989, it has been a relatively short time for a radical change to come. It requires development, confrontation with the world. However, the First Republic lasted twenty years, so that’s not such a short period... M. D.: The problem is broader – the entire fluid of society would need to change. Specifically in Prague, the entire debate has revolved for twenty years around the fact that a certain group wants to fossilize the city and the other part, which desires to disrupt this rigidity, comes up with various topics like the panorama of Prague. For example, the issue of whether the Žižkov Tower disrupts the panorama resonates in society to this day. On these topics, I see that public opinion has practically not moved anywhere. J. Š.: Czech society is cautious. For example, in France, people know what will happen in the metropolis; the media inform them quite conscientiously about it, and ordinary people discuss in cafés what will be built, is being built, or has just been built. Here it is a very marginal matter, and only later does someone shout that it is big, ugly, and so forth. So do you feel that the situation is also due to the level of awareness? J. Š.: Definitely. Society has a debt to itself. Some time ago, I stopped looking for culprits. If we have to assign blame, then it’s everyone’s fault. At least my own and everyone else’s. It is true that society is a dynamic organism that cannot be controlled. Everyone of us should contribute to the discussion about public space. I personally try to contribute at home – and I’m not very successful at it. (laughs) My wife – although she’s intelligent – constantly sees that something is being halted somewhere again... And I often struggle to explain that the city is growing, that it is densifying, that it is an organism. She, however, sees shortcomings in the municipality. We can build a house, quite a reasonably sized one – after all, the participants in the proceedings agreed on it, but it needs to be connected to the infrastructure, kindergartens, and other facilities – which the city does not have anymore. Society is lagging behind in maintaining and complementing municipal infrastructure. And one cannot expect this from private investors. This is where I see a deficit: we should inform ourselves more and above all, request relevant information. All of us should push our representatives to improve the situation.

And do you do that? J. Š.: I always tell myself: I should. But like many architects, I have my hands full. There’s no time for it. One should make time for it, though. Architects should enter politics. But we are trying. For example, we did a very publicly monitored project on Buďánka. A project that was doomed to fail from the start. Under mayor Jančík, it was acquired by the Geosan company. We did it diligently, with construction-historical surveys, models; we tried to accommodate citizens' initiatives – and we were attacked in various ways, we explained at town hall meetings... I remember preparing at home constantly for what and how I would clarify the project to people during defense. But explaining is definitely important... J. Š.: Absolutely; you can't just take offense. First, we should try to understand the opinions of people who live in the given environment… And what was the main point of contention at Buďánka? J. Š.: We needed to ensure that besides restoring the original houses, new buildings would also be constructed. So a financial model would arise that would allow the project to be realized at all. However, most people felt that the new buildings were too big. They believed they would create disproportionate profits… The extent to which Buďánka needs to be reconstructed was continually sought. Moreover, during a period of slight hysteria, with a feeling that they were slowly collapsing and will vanish… We reconstructed them to their original state, according to period photographs – we called it the original image of the area. As if you were repainting a painting. Which is a philosophical question: to repaint or not. We repainted the image. And we built new, contemporary buildings in the places where the houses used to stand along Plzeňská Street. However, objections still revolved around the fact that the new buildings were too large; locals wanted something smaller, ideally co-housing, workshops, and so on. But if you imagine that the original Buďánka were mostly built by workers from leftover stone they found in the former quarry and from other second-rate materials, and have been decaying ever since – it is basically a slope that, along with the remaining buildings, is sliding down... The investor cannot just slightly restore the buildings, although that might be possible for the three lower ones. Buďánka is a typical task for the city. It’s a social challenge. You mentioned that it is difficult to realize quality larger buildings in the Czech Republic. Does your office participate in competitions? Do you believe in this form of gaining, for example, larger contracts? J. Š.: It is true that we have not competed in the last two years. For a competition to be done honestly, it costs something – it’s expensive. Working on it costs eighty to ninety thousand. In the past, we won a competition for the interior of the Senate meeting hall, a competition for the interior of the presidential bathroom at the castle – and then nothing. We came to the conclusion that we are not ideal "competition" architects. We do not have the right nose for public competition… M. D.: Moreover, there is a certain historical personal experience. You invest energy into a competition, give quality to the design, spend time on it... and then you see how the competition turns out. Enthusiasm decreases... However, I’m not saying that this is the case across the entire country.

Are you talking about a specific competition? M. D.: I would prefer not to provide examples. J. Š.: You have touched on a topic that troubles us... When we look at the ongoing competitions, there are public spaces between schools in Kostelec, revitalization of a street in Kolín, revitalization of the town center, a multifunctional building in Janské Lázně – it is true that it is some kind of building... And then there is Prague 5: it concerns a place where Geosan originally planned the construction of apartment buildings, which the city stopped. Now the city has taken it upon itself and in cooperation with citizens, prepares a project for park improvements. But if you ask the people what they want, the answer can be surprising, misleading, influenced by the momentary mood. Similarly, as when people were asked about Brexit in England. People have chosen democratic institutions, and they should rule over them. Not everything can be a subject of a referendum. However, people should be proactive in supervising what is going on. M. D.: When you drive through the Benelux or Switzerland, look at how the villages there look. And definitely, it is not just the intelligentsia living in them. When you go to an electrician's house, you might find exclusive pieces of furniture there. They want quality…

What do you think causes the low demand of Czech society for quality architecture and design? M. D.: Absence of tradition. Break of ties. In the First Republic, there was social demand. J. Š.: My grandfather was a leather craftsman, upholstering bus bodies with leather, but at home, he had quality tubular furniture. I read somewhere that as long as social norms decay, they must be repaired for just as long. So we are still facing another twenty years. M. D.: But to not be just pessimistic: there are several legitimate steps in the form of architectural servers and magazines – but again, they turn back to the community. However, that community is informed. The problem remains society as a whole. It is true that in non-professional media – including public television and radio – an architect's name is mentioned only exceptionally. Unlike the investor or politician who cuts the ribbon... M. D.: Once again, I would refer to the break of ties. The society's perception of the architect as some bourgeois, something that only the elite could afford, persists. This is of course not true. In public space, we see that the need for an architect is the same as the need for a doctor. The visual environment needs to be healed. J. Š.: I have personally adopted the term micro-social engineering for this topic – a term that I borrowed from Cyril Höschl. If I do not publicly engage, I must consistently perform micro acts – if I meet someone expressing misleading opinions on architecture and city creation, I don’t let it be and try to engage them in a discussion and explain the topic to them. Furthermore, our office strives not to let even the smallest project lack high quality. This too is a form of micro-social engineering – to add a quality endeavor to the space.

J. Š.: We are daily addressing the disorder between the invalid building regulations in Prague and the postponed validity of the new ones... How does this situation specifically affect your work? J. Š.: Incredibly. With one or two projects, we get into a vacuum. We are exposed to nationwide regulations that are not suitable for Prague. Prague is a specific case, which is why it has always had its own. Some buildings are simply unfeasible in the intent we had before the expiration of the Prague regulations. Many projects are stalled and waiting. Can you provide a specific example for lay readers? J. Š.: For example, the size of the building is now governed by the ability to drain – infiltrate rainwater on the own plot. If you don't have a storm sewer or a combined sewer, which is far from being everywhere, you have to deal with it on your own land. However, Prague is predominantly situated on clays and decomposed shales and infiltrates poorly... So for example, you end up in a situation where the size of the infiltration bodies is larger than the land itself, without anything even standing on it. What then to do? So you are already looking forward to August when the new building regulations come into effect. (the interview was conducted at the beginning of July 2016 – editor's note.) RETURNS Allow me to conclude with a holiday topic: You returned from a joint vacation. Why did you decide for the third time to go to the same place? M. D.: Although we have a number of friends in the south of France, in Spain or Italy, or in other interesting destinations, the combination of all factors and the feeling that we take away from the holiday is so unique that I have never encountered anything similar. The situation also changes with more children; I myself am the father of two. One has to adapt the concept of vacation to this reality. Thanks to our friends who are sailors, we stumbled upon a place that is perhaps unknown, a somewhat forgotten world within Croatia... I admit that I originally had an aversion to this country due to the massive influx of our compatriots...

M. D.: On Dugi Otok Island – a long island that is 40 kilometers long, with several villages and one larger port. A very intimate atmosphere, you descend from the mountains down a rocky path, around fishermen's houses, to your private beach... And will you reveal the name of the place? M. D.: It has none. It is nameless. In the bay stood a stone house where locals used to go fishing. Over time, it became a kind of cottage, which they began to call a "víkendica" (weekend house). As a source of livelihood, they added one or two apartments, but the environment remains authentic. J. Š.: The owners are eighty-year-old folks, we fear that with their passing, this place will also vanish. That their son will not maintain it, or modernize it. There is no running water there today. They only have water that collects during the winter. It also serves as a kind of natural air conditioning: the tanks are largely placed under the house. Is this water drinkable too? M. D.: Yes, it doesn't spoil. Can you define what is the most unique aspect of your holiday? M. D.: The indescribable and intransferable. Open sea, a small bay. There is no electricity, no mobile phone signal, no internet connection. You have to go fetch water. You read a book by candlelight. A return to the roots – a paradox of today: you now have to pay for the absence of luxury. Thank you for the interview. Kateřina Lopatová The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

:-)

Pavel Vrága

26.08.16 11:36

show all comments

|