At one time, Jiří Knesl and Jakub Kynčl were among the most prominent figures at the Brno Faculty of Architecture. Choosing them as the leaders of studio work meant for the student to come to terms with a challenge that was not entirely common for this school at that time. They were preceded by a reputation for being demanding yet dedicated teachers – and this was evident in the works they led. The same was true during their long-term involvement in the academic senate or directly in the faculty's management. "When we do something, we want to do it wholeheartedly. We are willing to take on responsibility, but we also want to have the authority," recalls Jiří Knesl. At one time, Jiří Knesl and Jakub Kynčl were among the most prominent figures at the Brno Faculty of Architecture. Choosing them as the leaders of studio work meant for the student to come to terms with a challenge that was not entirely common for this school at that time. They were preceded by a reputation for being demanding yet dedicated teachers – and this was evident in the works they led. The same was true during their long-term involvement in the academic senate or directly in the faculty's management. "When we do something, we want to do it wholeheartedly. We are willing to take on responsibility, but we also want to have the authority," recalls Jiří Knesl. It is almost incomprehensible that alongside their work in the academic sphere, they were also fully dedicated to the operation of their own architectural office. It was only a few years ago that they began to focus exclusively on practice. Even here, each of their projects shows that they have high expectations for themselves, their colleagues, and undoubtedly also for their clients. Over the fifteen years of collaboration, the number of their projects is slowly approaching four hundred. Their thematic range extends from urban plans, through residential complexes, proposals for public spaces, to individual family houses, small buildings, interiors, and even graphics. Until early March, it is possible to visit their exhibition Between the City and the House at the Jaroslav Fragner Gallery, which stands out from other similarly focused exhibitions. Jakub Kynčl says: "We didn’t want a traditional architectural exhibition with posters, and at the same time, we are not visual artists to create some installation." Therefore, they preferred to select eight designs to showcase their way of thinking. The most suitable are competition projects, in which "the original idea is displayed in a crystalline form, not yet clouded by discussions, optimizations, the method of realization, etc." Compared to other exhibitions, visitors may also be surprised by the amount of text in which each proposal is placed in broader contexts. Other works of the knesl + kynčl architects studio are presented through several photographs in the foyer, an online presentation on two computers, and also in a newly published booklet-catalog. A pleasant highlight is the amusing illustrated commentaries by Jiří Knesl. The day after the opening, we met with Jiří Knesl and Jakub Kynčl for an interview in their Brno studio. It stretched into the evening hours; however, even after our farewell, both headed to their colleagues to complete their ongoing work.

Jakub Kynčl (KY): The revolution was a crucial life experience for both of us. Jiří was in his fourth year, I was in my first year. The school reflects what is happening in society with all its pluses and minuses. These are the same things, just rewritten into an academic environment. So the school was very fun between 1990 and 1992. It was a time of freedom. Just like the newly breathed society, it was all very emotional, filled with positive ideals, and that was exactly what was happening at the faculty. Many inspiring people came from outside with something to say. But they stayed for two years, then they understood it probably wasn’t the right environment for them, and they packed up and walked away. Then it gradually started to decline, it was beginning to normalize, and it fell into established routines, and it continued this way step by step. We left the school four years ago because the office had grown, we had small children at home, three-shift operations were no longer manageable, and maybe after twelve years it was time for a change. Recently, I visited former colleagues and heard how things had changed in those four years, that they were only dealing with administration and hardly teaching anymore. Jiří Knesl (KN): I am glad about that time, but thank you, that was enough. Why did you decide to stay at the school and teach? KY: We simply enjoyed it. For example, consulting on ten completely different projects in one afternoon, where a person has to switch their perception with every student and try to tune into how they see things, understand why they did it that way, and not just look at it through their own perspective. That was great training, and we enjoyed it. When we finished and looked back, we realized that we had worked with more than 300 students, which is something incredible. When did you realize that your collaboration was functioning? KY: We knew each other from school because it wasn't very large back then. About two hundred fifty people, all of whom knew each other at least by sight. But at that time, we did not yet have the ambition or plans to work together. Only when we met years later, one word led to another, and it started. I was a little surprised when I heard somewhere how often with other pairs of colleagues each of them works independently. It's not like that for us. We truly operate as a pair, meaning we design together. Each of us is a bit different, but we easily agree on basic things. Discussion is extremely important for every project. So both of you work on the same projects, do you both keep track of every project? Today, it cannot be said that this is the case for all projects. As long as there were fewer than ten of us in the studio, we more or less knew everything about all projects. Perhaps one of us had a project a bit more under control, but the other person could always jump in, and we found that this interchangeability or substitutability was quite important. Now we don't have the same level of oversight over all projects. In the beginnings, we discussed everything together, and then it was such that one of us leads either the project or its part. KN: It works excellently. When did you decide to set up your own studio? KY: The first decision was made back in 1999, but we fully committed to it only in 2001. Until then, we had already done something together or regularly discussed various things. KN: Among other things, we participated in competitions, at that time still with Milan Stehlík.

In a relatively short time, you have grown quite significantly. Did you notice any need to change your work organization? KY: That's a question we constantly deal with. We still try to be an authors' office. We are involved in everything, we try to maintain control over everything from start to finish so that it truly remains an authors' affair. On the other hand, we struggle with delegating authority. When there were about eight or ten of us, it was pleasant; we could sit in the studio, draw something, and it was enjoyable work. But suddenly we realized that we were no longer capable of handling some larger projects in that composition. So we are constantly balancing between two positions: being able to offer the professional performance of a larger office while still maintaining some control over everything. KN: In the beginning, we had nothing but those two names. That has carried through with us; it’s no longer just those names, but rather it’s a brand. When someone orders us, they want to speak directly with both of us. We cannot send someone else in our place. The maximum number of people in the studio is around twenty-four, because after that, you start getting additional departments that do not produce but consume. With this number, we can manage some things very quickly; in smaller numbers, it wouldn’t work. How do you design? Do you use working models, sketch? KY: We usually design in the last fifteen minutes before leaving home, after eight in the evening. We put a piece of paper in between, one person scribbles on it, gestures with their hands, and the other scribbles from the other side. KN: One of us usually carries the idea in their head for some time and - which is important - is prepared for the discussion. The other one somehow opposes it. KY: We don't talk much. Because we don't have to. After all these years, a few lines are enough for the other one to understand. Then we also work a lot with models. We have a separate model workshop where both working models and those with which we then present to clients are made. We found that many people do not understand images, not even visualizations. The image is too abstract to understand the specific view from where it is led. Models for presentations work one hundred percent. Between the City and the House

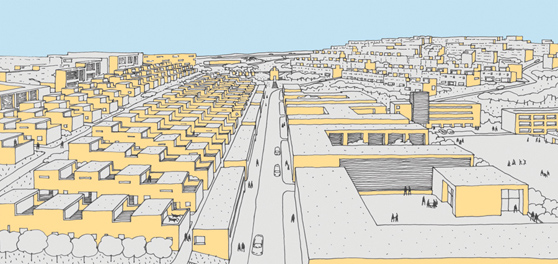

KY: Both of us graduated from the Institute of Urbanism and then had experience in urban studios. Urbanism was basically a dirty word in the 80s and 90s. Spatial planning and architecture were totally torn apart. It is no longer the case today. KN: Architects were then the artists, and the rest were the planners. For Urban Interventions in 2011, you created the project for the so-called South Center in Brno, which was supposedly connected with your professional beginnings. When did you first start dealing with this area? KY: We both did the South Center in Brno as school projects. Then in 1992, a competition took place. It is a large area, a challenge that lasts. KN: I was working in the UAD studio at that time and during the competition, I received completely free rein. It was the first big thing where I started with a blank sheet of paper. It was a lot of fun. In the texts for your exhibition, you often refer to the ideas of Spanish architect and urbanist Oriol Bohigas. What attracted you to him? KY: I discovered him around the mid-90s. Post-war architecture was not much taught here, and probably still isn’t, so we caught up on it only after school. What we are talking about is the principle of urban projects. We are very interested in the moment when the city meets the house itself. The public intertwines with the private.

Recently, questions concerning the degree of regulation in spatial planning have been increasingly raised... KY: That is an eternal debate. We try to adhere to one principle: we try to regulate more what is public, less what is private. That means not to interfere too much in private areas, to provide a basic framework mainly in relation to the public, and leave the rest to the owners. Unlike the public part of the city, where we believe that regulation should be quite strict, although an over-regulated plan is a bad plan. KN: When architects do urbanism or spatial planning, they try to regulate according to the houses they themselves would design there. Which is, of course, nonsense. On the other hand, if we leave space for the architects who will come after us, we also give them responsibility for that place. But then you can debate for a long time about the quality of our profession and the people who ultimately draw those houses... To what extent do your works on projects of various scales influence each other? KY: The fact that we work on individual houses and urban plans is important, and it helps both positions. In each of them, we are aware of the other. So when we are working on some urban solution, we are always thinking about how specific houses can be built there, how they will function. Conversely, at the moment when we design a house, we consider its functioning within the city and the environment, whether it won't become just a beautiful sculpture about nothing. KN: When in the land use plan we use red for residential areas, we have to know that there will be apartments in the houses that are for example illuminated. Many other "land planners" do not realize this and areas are designed in such a way that a residential building cannot be placed there at all. KY: It is interesting when we receive a project for a house or a complex of houses in a city where we are doing the land use plan. We know the connections perfectly and can focus on the detail itself. That’s very pleasant. In the process of spatial planning, the communication between its author and processor with the public is very important. While working on the land use plan for Kuřim, you used the comic form to explain its principles. How was that received? KY: For a certain age group of Kuřim residents, it elicited positive feedback. Comics is a form of communication that is close to us. Jiří constantly comments on life in the office with some images and caricatures. Although I do not know whether the comic form is the completely right or most appropriate form of promoting a land use plan, what matters is that it can engage people. KN: When a decree is posted somewhere which meets the required criteria, no one understands it. But when a person summarizes it into three sentences and adds a funny picture, it may interest someone enough to attend a public meeting. The scheme of that discussion process worked excellently. We use it practically all the time. However, turning it into a story was complicated. The characters, casting, and adding something more than just the dull descriptive text. A certain counterpoint to designing land use plans is a whole range of family houses in your portfolio. At first glance, the huge influence of Brno's interwar functionalism is evident in them. To what extent do you feel you are following in the footsteps of your Brno predecessors? KY: In Brno, one cannot avoid that in any case. But we do not have any syndrome in that respect. The interwar period had the ethos of great positive development, and remarkable quality things were created. So that is definitely inspiring. But we are also influenced by many other things, and even though we quite like whites and squares, we certainly do not only design them. KN: It can also be simplified a bit. It is not so much functionalism as geometric abstraction. It’s simple. When a person dives into it, they always find a solution. KY: It’s also a generally understandable principle. KN: For me, that ends figurative art. A white square on a white background is the end. There is nothing behind it. Then it’s just some hodgepodge or some big joke. Until the end of my life, I can probably manage with that. We used school for that – as a laboratory. When a student wanted to go somewhere, we supported them and found out if there was something worth developing. And we realized that a right angle is a right angle. All construction systems are adapted to it; everything else is expensive – and thus bad. We try to enliven it, responding to the situation of a specific place. KY: For example, in Oslavany. The bend of the river – it was clear that an arc had to be there, and there was no discussion about it. Or in one family house in Svinošice, the arc connects a place of entry, which was clearly defined, and a place of view over three horizons. And it was the arc, the path that led us there. KN: What was interesting there is that a person does not open a door and it hits them in the face – they must go down a hallway, the element of surprise works.

KY: The perception of architecture by society was quite different ten years ago. Back then, there were long hours of showing various pictures, convincing that a modern house does not have to be cold and uninhabitable. Today, clients come with relatively clear expectations based on what they have seen. We no longer have to convince them as much. The explanations are now shifting to details. KN: However, what is important is that in the first phase, we do not draw, but we talk with people about what they want. KY: The language is very tricky, and architecture uses the same expressions as common Czech language. We picture something different under those words than clients do. That is why it is important to have long discussions at the beginning to find out what truly stands behind the words. For this reason, we propose in variants at the beginning. And we design very different variants for the simple reason that there should be no doubt that the right path has been chosen. If you do not convince the client, do you terminate the collaboration? KN: Yes, it happens. Otherwise, it would be a struggle for everyone. KY: If it doesn’t work from the beginning, it cannot end well. But how do you design residential complexes, for which you don’t have specific clients for each of the houses? KY: For an anonymous client, a type of space must be created that is, to a certain extent, universal. It cannot be occupied in just one way. It is livable by various people, whether by age categories or lifestyles. In this regard, it is more complicated because the individual client will tell us what they want, while here we must think about it for all future residents. You are the authors of the ecological center in Javorník. What is your view on the trend of low-energy or even passive construction? KY: The passive standard is a bubble. But environmentally friendly and low-energy construction is certainly not a bubble, although we can perhaps call it something different. Such as smart construction with informed tradition. Whether this house has more or less insulation is not important. The fundamental structure and orientation of the house are significant, and that is where the smartness or foolishness of the house lies. KN: We are interested in simple things. Complicated ones do not work. Complicated ecological solutions are useless. KY: And what does "ecological" even mean? I don’t know... KN: I see it more like needing to do things simply in construction. That means not to have silly details, unnecessarily cooled surfaces. That’s why we also focus on construction to have it under control. The details are invented by architects.

About CompetitionsYou often participate in architectural competitions. What attracts you to them?

KN: Freedom. KY: It’s nice to gain a project from a competition, but that’s not the most important thing. What matters is the experimentation. In concentrated time, a person has the chance to reach for something they would never otherwise experience in their professional life, such as the National Library in Prague. KN: One usually does not get to try out a building worth three billion. It is also important for team bonding. When working overnight on competitions, the group operates differently than on regular projects.

How do you choose the competitions you participate in? KY: In the Czech Republic, we are interested in the jury. Otherwise, it’s always the topic. KN: We did a competition for Mexico. There are few competitions where everything is done from individual houses to urbanism. We do not often get to do that otherwise. Of course, within the work on land use plans, we draw structures to ensure we can fit roads and sewers in. But these are merely indicative sketches. It’s at such a competition that there is a chance to think the city through to the end, how it works.

KY: That was coincidental. They all came together in one year. KN: The competition in Havlíčkův Brod was beautiful, a difficult place. We had to do the National Library even though many people advised us against it. And we both love Asplund’s library in Stockholm; it is one of the strongest buildings we know, so it was a challenge. Shortly after that, you managed to win the competition for the city hall and hall in Jeseník. However, the joy of victory probably did not last long as the city eventually decided not to implement the project, favoring investment in an aquapark instead. How do you recall this competition? KY: Such is life. We are sorry because we liked that project a lot. KN: It went well with the jury and the “voice of the people.” We were happy about that. KY: We were initially worried about that “vox populi” voting. We expected that the public and the expert jury would not agree, and here agreement was achieved. So it was a good constellation, and we were looking forward to the continuation – and there is no continuation...

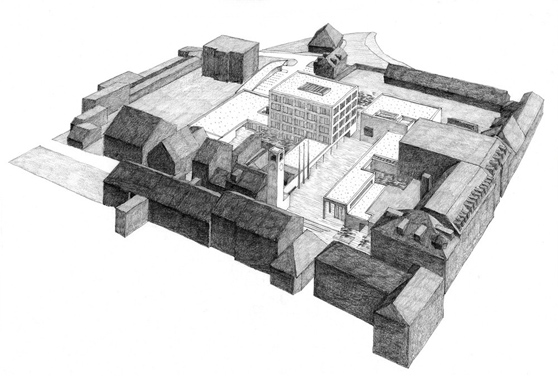

You have also had the opportunity to serve as organizers of competitions several times. For the Brno University of Technology, you prepared a competition for the campus of the Faculty of Architecture and Fine Arts, organized two competitions in Kuřim, and two years ago, a competition for Římské náměstí in Brno. How did you get into the role of organizer? What is better about organizing a competition than participating in one? KY: A few times we said that it is better to help create something meaningful from the other side than to have to necessarily participate. For example, in Kuřim, we are doing the land use plan, so we helped the city to organize the competitions. At VUT, we once pushed for a competition for the area of Údolní 53 – and then it was logical that we should help with its organization. It is good to master all three positions in competitions – competitor, juror, and organizer. Only when we know all three positions are we able to set the competition well because we perceive how competitors and jurors will view it. How do you perceive the quality of domestic competitions from this perspective of three different sides? KN: It depends on the jury. KY: It greatly depends on the organizer, whether they engage with someone who has experience with competitions. Organizers are usually cities that often appoint some official to manage the competition. Even when there is a good jury present, the competition may not go well because it is poorly organized. Moreover, Czech jurors often have the bad habit of not reading the competition conditions beforehand, not making comments, and starting the judging only when the proposals are already on the table, and then it is discovered what is wrong. KN: When jurors designated by the chamber are involved, a certain group meets where each juror assesses the house based on how they themselves would draw it. Which is the worst thing that can happen. A juror must be selected in such a way that they humanly get along, that they are prepared for judging, that they do not preempt solutions but try to select not only the most creative proposal but also the one that best meets the criteria and will be “manageable” in the future by the city or other organizers.

The Ideal Project is a City Building

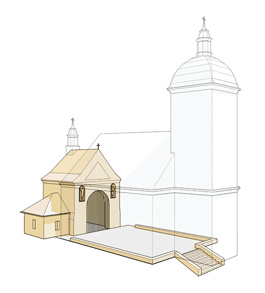

KY: We don’t plan much. The ideal project for us is something like the office proposal for Jeseník. A city building. We were really looking forward to that, it was a pleasant scale, a nicely sized building, but not unnecessarily large, in a great environment, with an amazing program, intertwining everything possible. But everything arrives gradually somehow. We like all the things we have done in their own way. We wouldn’t even think that we would be doing some chapel of Saint Roch above Uherské Hradiště. We were originally only tasked to repair the façade, and suddenly it became something different, and that made it even more fun. KN: That chapel seems like an ideal project to me. When it starts as some kind of unwanted child, and suddenly something happens. What was somewhere in the sixth entry in twentieth place, that the façade should be repaired, suddenly makes the front page of the local press, people like it, politicians, officials, and users start to love it. The construction company starts doing it with love. Suddenly you think it seems like complete nonsense, but it is beautiful. This profession is not pointless. I keep drawing things at night and wonder: does it make sense? And suddenly, with such “nonsense,” something happens, and I say: “yes!”. And it is better to do a small thing well than a big thing poorly. KY: An unexpected thing can be much more interesting than something planned. But we try to be prepared. We continuously observe something, study, read, but at the same time, we are open to the fact that something unexpected may happen. KN: You need to have the tubes warmed up. The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

2 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

výborně!

ondrej.vyslouzil

03.03.13 02:56

Tak nevím,

Marpen

04.03.13 12:20

show all comments

Related articles |