|

| Kuba Snopek (photo © Zarina Kodzaeva, 2016) |

|

| Kuba Snopek (photo © Zarina Kodzaeva, 2016) |

|

| Church of the Mother of God Queen of Poland [Matki Bożej Królowej Polski] in Kraków (photo © Maciej Lulko, 2015) |

|

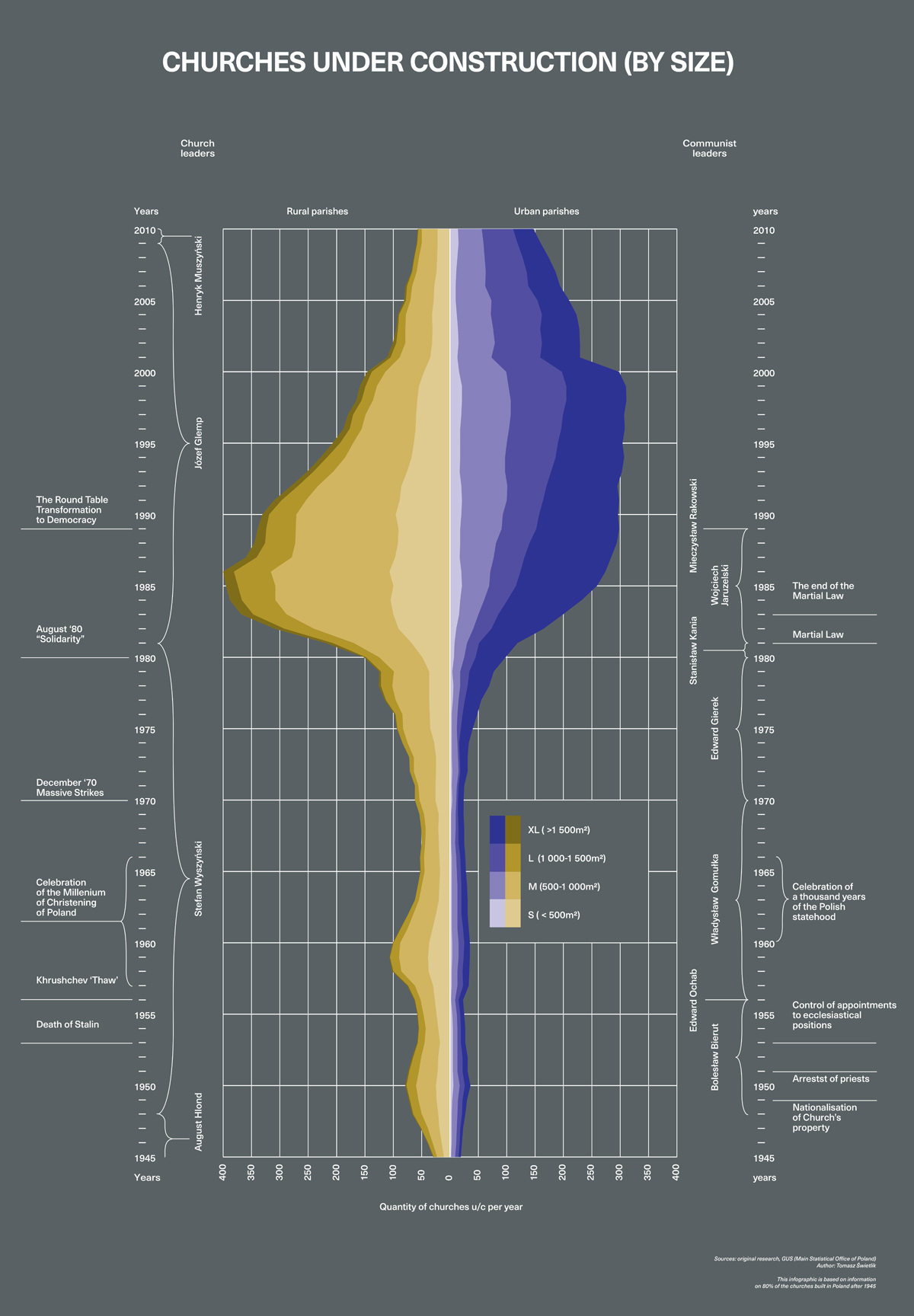

| Amount of churches built (by size) between 1945 and 2015 (© Tomasz Swietlik) |

|

| Interior of the Church of the Mother of God Queen of Poland [Matki Bożej Królowej Polski] in Kraków (photo © Maciej Lulko, 2015) |

|

| Church of Divine Mercy [Miłosierdzia Bożego], called “White Batman,” in Kalisz (photo © Igor Snopek, 2015) |

|

| Church of St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe [Świętego Maksymiliana Marii Kolbego] in Kraków, view from a 45° angle (photo © Igor Snopek, 2015) |

|

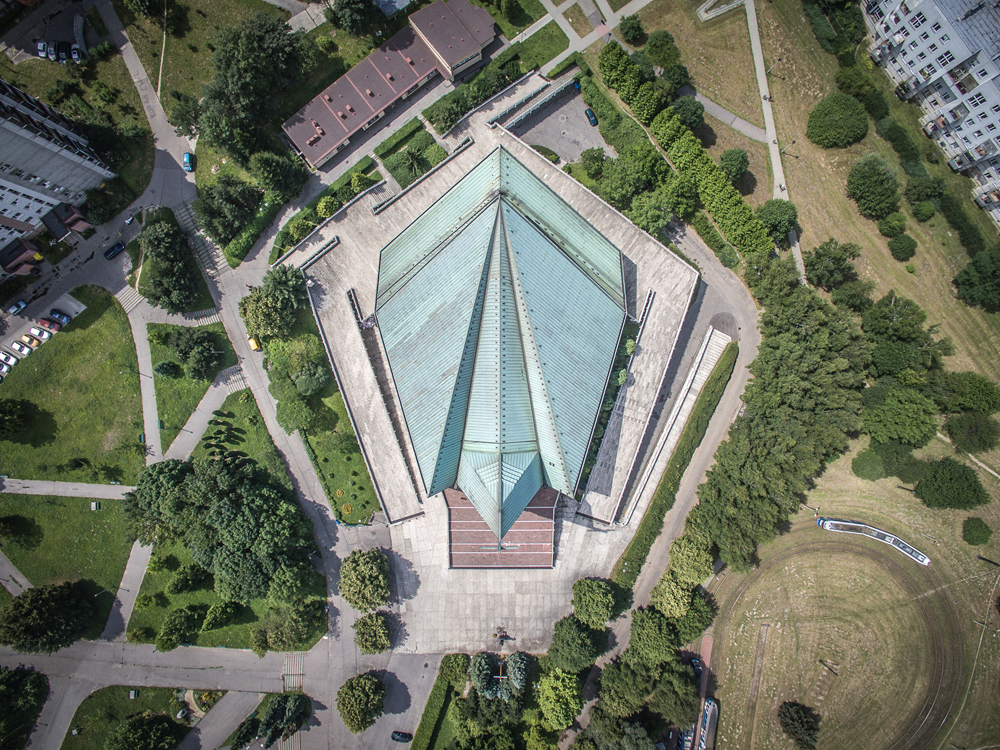

| Church of St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe [Świętego Maksymiliana Marii Kolbego] in Kraków, view from a height of 120 m (photo © Igor Snopek, 2015) |