Culture 24/7 presented by the Vltava Philharmonic – a foolish dream, or a near reality?

The new philharmonic in Prague has been debated for as long as the new train station in Brno. It is now even claimed that the architectural competition for the design of the building and the land is currently the most discussed in Central Europe. The ambitions are high, with expectations for top-notch acoustics, the creation of a center for cultural and social life in the area, and a new architectural icon for Prague.

In October of last year, 15 teams out of 115 registered architectural teams were selected, supplemented by 5 directly invited firms (Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Snohetta, Ateliers Jean Nouvel, David Chipperfield Architects, SANAA), and they will compete in the design competition for the Vltava Philharmonic building. The results of the competition will be announced in April of this year, and it can be assumed that the announcement of the winner will provoke lively reactions, just as had occurred with the announcement of the construction site's location. What does the competition brief look like and what are the expectations?

Looking into history, no concert hall for symphonic music has been built in Prague for more than a hundred years. Roman Bělor, the director of the Prague Spring Festival, claims that excellent music from the 19th century is performed in the existing venues (Rudolfinum from 1885 and the Municipal House from 1914), but newer works present challenges. According to Daniel Sobotka, director of FOK, the new philharmonic aims to present the productions of Czech orchestras to citizens in a way that they have only been able to hear on their foreign tours until now.

Concert halls are also being constructed in Brno and Ostrava – specifically the Janáček Cultural Centre, emerging from a design by Atelier M1 architekti s.r.o., and the Concert Hall Ostrava by Steven Holl Architects + Architecture Acts. This raises the question of whether there is indeed enough demand for musical programs in our country to sustain these three (extremely financially demanding) buildings. According to Martin Gross, a member of the Vltava Philharmonic project team, a greater number of halls could attract numerous foreign ensembles, for whom it is more lucrative to perform multiple shows in one country during world tours. According to Deputy Petr Hlaváček, this is about the Czech Republic returning to the global music map, and he sees classical music as a means of combating the digital destruction of the world.

The tram line will also be shifted. However, the area will continue to be burdened by traffic (cars, trains, trams, metro) and related noise pollution; according to Petr Hlaváček, the combination of various types of transport in the area is unique and very advantageous despite requiring greater costs for sound insulation in the concert halls.

The construction of the philharmonic also aims to accelerate the development of the adjacent Bubny-Zátory brownfield, where a new multifunctional district should be created between 2025 and 2040 with 60% residential building. However, as admitted by the mayor of Prague 7, Jan Čižinský, the apartments here will be very expensive, as the land does not belong to the city, making it impossible to moderate rising costs other than acquiring city apartments, which is a lengthy process. It is said that the newly approved Methodology for the Co-participation of Investors in the Development of the City of Prague's Area should help in this.

High expectations also exist among independent architects. David Kudla (dkarchitekti s.r.o.) claims that philharmonic buildings are modern cathedrals and hold the highest prestige today. According to him, the Vltava Philharmonic should become “a modern icon of Prague, demonstrating that this beautiful historical city is also a modern metropolis.” Jakub Heidler from Studio Reaktor s.r.o. expects “a European (maybe global), exceptional architectural achievement that will attract many visitors not just for the culture but also for the building itself.”

What, however, provoked mixed reactions was the decision to hold the competition as a single round – according to Jan Aulík from AFARCH, this is a correct approach as it allows for a strong, subjective concept to emerge. The biggest risk of the project, he sees, is that the urban quality in the immediate vicinity of the philharmonic still needs to be established, and the current state is more an investment burden than an appropriate context. Tomáš Horalík (Horalík Atelier) on the other hand, would have expected a two-round competition due to the significance and complexity of the building – he perceives the chosen solution as an attempt to simplify and expedite the entire process. Radim Horák (KAMKAB!NET) points out that this choice means losing the opportunity to clarify and further develop things in the next round. He states that, for example, with the competition proposals for the new main train station in Brno, it became clear during further development that not all solutions are as good as they seemed in the first round.

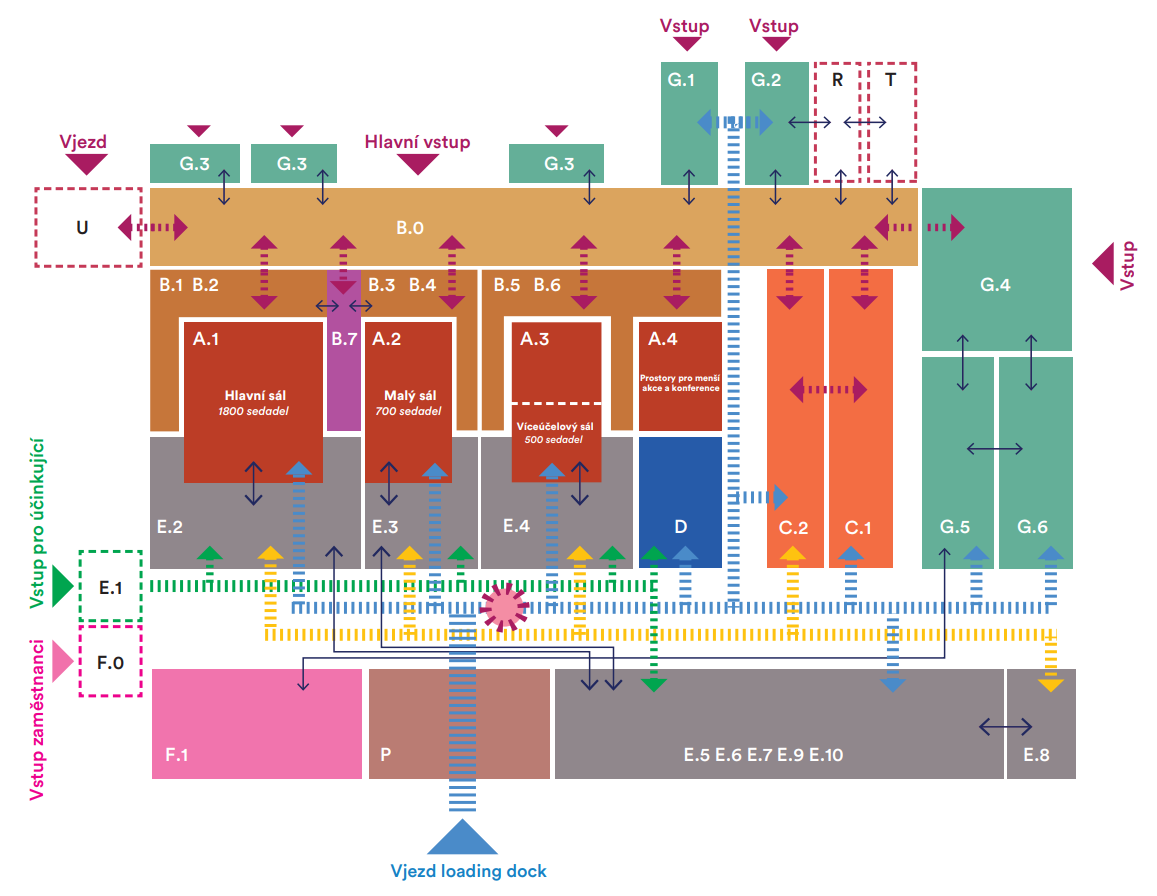

The actual competition brief spans more than 80 pages and focuses on presenting the context of the planned building. Within the section of the construction program, the users of the building and resident organizations are characterized, and individual sections that the building must include (along with their net and gross floor areas) are listed – halls, foyer, creative hub, facilities for artists and production, building management, operations, and gastronomy. The sections consolidate individual rooms, clearly defining their function, capacity, and floor area. An operational plan is also provided, describing the relationships between individual spaces and the routes for visitor, performer, and supply movement. The proposal must also present a solution for the land, including the cultivation of the embankment (approximately 4,500 m² of public space).

Additionally, the project may be thwarted by the long-discussed debt brake – the Ministry of Finance's plans last year counted on reaching this limit in 2024. That is, a year before the approval of financing for the 3rd phase of the project (approximately 5.3 billion CZK). At that time, the willingness of private investors, who should provide one-third of the funds for construction (the second third should be provided by the city and the last by the state), will also manifest. However, Petr Hlaváček emphasizes that 50% of the intellectual and financial costs have already been utilized for preparing the land in the 1st phase of the project (analysis), zoning plan changes, and transport route adjustments. This groundwork could also be used for the construction of another cultural building.

With adjustments to the transport arteries in the area around Hlávkův Bridge, there are also underpasses that the city, along with Prague 7, had modified last year for approximately 2.5 million crowns according to a design by Bajkazyl and architects from U/U studio. Originally dark and unattractive underpasses have been newly adjusted to be barrier-free and transformed into sports facilities intended for skateboarding, bouldering, and basketball. However, the question remains how many underpasses in the area will remain.

|

In October of last year, 15 teams out of 115 registered architectural teams were selected, supplemented by 5 directly invited firms (Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Snohetta, Ateliers Jean Nouvel, David Chipperfield Architects, SANAA), and they will compete in the design competition for the Vltava Philharmonic building. The results of the competition will be announced in April of this year, and it can be assumed that the announcement of the winner will provoke lively reactions, just as had occurred with the announcement of the construction site's location. What does the competition brief look like and what are the expectations?

Looking into history, no concert hall for symphonic music has been built in Prague for more than a hundred years. Roman Bělor, the director of the Prague Spring Festival, claims that excellent music from the 19th century is performed in the existing venues (Rudolfinum from 1885 and the Municipal House from 1914), but newer works present challenges. According to Daniel Sobotka, director of FOK, the new philharmonic aims to present the productions of Czech orchestras to citizens in a way that they have only been able to hear on their foreign tours until now.

Concert halls are also being constructed in Brno and Ostrava – specifically the Janáček Cultural Centre, emerging from a design by Atelier M1 architekti s.r.o., and the Concert Hall Ostrava by Steven Holl Architects + Architecture Acts. This raises the question of whether there is indeed enough demand for musical programs in our country to sustain these three (extremely financially demanding) buildings. According to Martin Gross, a member of the Vltava Philharmonic project team, a greater number of halls could attract numerous foreign ensembles, for whom it is more lucrative to perform multiple shows in one country during world tours. According to Deputy Petr Hlaváček, this is about the Czech Republic returning to the global music map, and he sees classical music as a means of combating the digital destruction of the world.

The construction of the philharmonic as an impetus for regional development

The plot of land for the future philharmonic is currently crossed by a tram line and an exit from the north-south expressway, making it poorly accessible (for example, pedestrians must go under the expressway) and not inviting for longer stays. To relieve the land from traffic burdens, an adjustment of the intersection including the cancellation of the northeastern return ramp – the exit from Hlávkův Bridge to the Kapitána Jaroše embankment – is proposed within the transport adjustments around the base of the bridge, which will be replaced in the future by an adjusted northwestern ramp. |

The construction of the philharmonic also aims to accelerate the development of the adjacent Bubny-Zátory brownfield, where a new multifunctional district should be created between 2025 and 2040 with 60% residential building. However, as admitted by the mayor of Prague 7, Jan Čižinský, the apartments here will be very expensive, as the land does not belong to the city, making it impossible to moderate rising costs other than acquiring city apartments, which is a lengthy process. It is said that the newly approved Methodology for the Co-participation of Investors in the Development of the City of Prague's Area should help in this.

What is the competition brief and what can be expected?

The project for the Vltava Philharmonic aims to be (at least according to the competition brief) a perfect instrument, a focal point connecting Lower and Upper Holešovice, a driver for changes in the area, and last but not least, a modern alternative to the historical center. In the discussion, the building was even referred to as a lively and continually open center of cultural and social life in Prague 7. However, Jan Čižinský believes that the building will become more of a center for leisure activities than a cultural and social center for the area.High expectations also exist among independent architects. David Kudla (dkarchitekti s.r.o.) claims that philharmonic buildings are modern cathedrals and hold the highest prestige today. According to him, the Vltava Philharmonic should become “a modern icon of Prague, demonstrating that this beautiful historical city is also a modern metropolis.” Jakub Heidler from Studio Reaktor s.r.o. expects “a European (maybe global), exceptional architectural achievement that will attract many visitors not just for the culture but also for the building itself.”

What, however, provoked mixed reactions was the decision to hold the competition as a single round – according to Jan Aulík from AFARCH, this is a correct approach as it allows for a strong, subjective concept to emerge. The biggest risk of the project, he sees, is that the urban quality in the immediate vicinity of the philharmonic still needs to be established, and the current state is more an investment burden than an appropriate context. Tomáš Horalík (Horalík Atelier) on the other hand, would have expected a two-round competition due to the significance and complexity of the building – he perceives the chosen solution as an attempt to simplify and expedite the entire process. Radim Horák (KAMKAB!NET) points out that this choice means losing the opportunity to clarify and further develop things in the next round. He states that, for example, with the competition proposals for the new main train station in Brno, it became clear during further development that not all solutions are as good as they seemed in the first round.

|

The actual competition brief spans more than 80 pages and focuses on presenting the context of the planned building. Within the section of the construction program, the users of the building and resident organizations are characterized, and individual sections that the building must include (along with their net and gross floor areas) are listed – halls, foyer, creative hub, facilities for artists and production, building management, operations, and gastronomy. The sections consolidate individual rooms, clearly defining their function, capacity, and floor area. An operational plan is also provided, describing the relationships between individual spaces and the routes for visitor, performer, and supply movement. The proposal must also present a solution for the land, including the cultivation of the embankment (approximately 4,500 m² of public space).

|

Snags, obstacles, hiccups – what are the construction problems?

However, not everything is as rosy as it may seem at first glance. According to the results of a sociological survey (p. 41), only 16% of respondents are concerned about rising rents in the area, but a impact analysis directly counts on this, as the philharmonic will increase the attractiveness of the entire locality. It also anticipates that rents will rise as early as this year due to the approval of plans to revitalize the area and the announcement of the architectural-urban competition. However, according to Jan Čižinský, mayor of Prague 7, it is impossible to moderate this price increase leading to gentrification – there are only very few city apartments in the area. Discussions are currently underway about further construction of city apartments in the Vltava and Bubny-Zátory areas. It is fair to say that any cultivation of the area or significant construction increases rental housing costs, but it is not possible to claim that this is not a problem.Additionally, the project may be thwarted by the long-discussed debt brake – the Ministry of Finance's plans last year counted on reaching this limit in 2024. That is, a year before the approval of financing for the 3rd phase of the project (approximately 5.3 billion CZK). At that time, the willingness of private investors, who should provide one-third of the funds for construction (the second third should be provided by the city and the last by the state), will also manifest. However, Petr Hlaváček emphasizes that 50% of the intellectual and financial costs have already been utilized for preparing the land in the 1st phase of the project (analysis), zoning plan changes, and transport route adjustments. This groundwork could also be used for the construction of another cultural building.

With adjustments to the transport arteries in the area around Hlávkův Bridge, there are also underpasses that the city, along with Prague 7, had modified last year for approximately 2.5 million crowns according to a design by Bajkazyl and architects from U/U studio. Originally dark and unattractive underpasses have been newly adjusted to be barrier-free and transformed into sports facilities intended for skateboarding, bouldering, and basketball. However, the question remains how many underpasses in the area will remain.

|

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment

Related articles

0

17.05.2023 | The detailed design of the philharmonic for the Prague Vltava will be completed in the autumn

0

28.03.2023 | Prague is preparing a model for the operation of the planned Philharmonic on the Vltava

0

11.10.2022 | Representatives of Prague signed a contract with the designers of the Philharmonic at Vltavská

15

19.09.2022 | The Philharmonic project on Vltavská will cost Prague more than a billion crowns

0

17.06.2022 | Praha will assign the winners of the competition to prepare the project of the philharmonic on Vltavská

0

14.06.2022 | The Philharmonic on the Prague Vltava will be more expensive, the new estimate speaks of 9.4 billion CZK

0

06.06.2022 | The council of Prague approved the funding for the preparation of the new Philharmonic project

23

17.05.2022 | The competition for the building of the Philharmonic in Prague was won by the Bjarke Ingels Group studio

1

17.05.2022 | In Prague today, the results of the competition for the design of the concert hall will be announced

0

11.04.2022 | The preparation of the new Prague Philharmonic will be taken over by the Prague Development Company

0

08.11.2021 | The designs for the new Prague Philharmonic will be prepared by 20 teams, with the Czech ones being in the minority

21

23.08.2021 | Prague with IPR today announced an international architectural competition for the design of the Vltava Philharmonic

0

12.11.2020 | Prague will change the zoning plan to allow the construction of a hall at Vltavská