Ladislav Žák: Garden, orchard, landscape as living space

When we talk about living space, we usually mean an enclosed building space of rooms, apartments, houses, and buildings. However, the primary living space of all living beings, including humans, has been free nature, which has maintained its residential character and significance throughout time. This has increased in our days with a new perspective on human health—and it will likely continue to grow through unforeseen development. After surprising technical victories of humanity over matter, which have, as has been rightly said, changed the face of the earth's surface more in the last hundred or hundred and fifty years than in all previous millennia. After all the great future achievements of human work that can be expected, humanity will always remain human, an organic being that is a part of nature, composed of the same atoms as the rest of the world and subjected to the same laws of mortal matter. The more advanced material and spiritual culture becomes, the more and more often humanity will need to draw strength from the earth, and the more intimately nature will become the home and dwelling of humankind.

It is hardly necessary to prove the self-evident fact that free space near our homes and houses, in our villages, cities, and in the open countryside should be living space, that our gardens, orchards, and nature are intended for human habitation, in a broader sense. From this basic understanding arises a series of consequences and requirements. First and foremost, we recognize that the living space of our gardens, orchards, and landscapes is part of a unified living space, the entire environment, whose organization, planning, and shaping is the task of architecture. — Truly contemporary architecture theoretically and practically strives to care for the entire human environment, starting with small items of life and housing needs, various tools, dishes, cutlery, housing components, and accessories (industrial and so-called decorative arts projects) through interior furnishings, furniture, installation items (interior architecture) to building projects of all kinds and sizes (building architecture)—and from there to large construction complexes, municipalities, and their parts (urban development)—and finally to the entire territory, landscaping, and planning (regionalism).

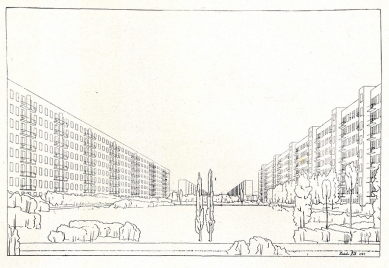

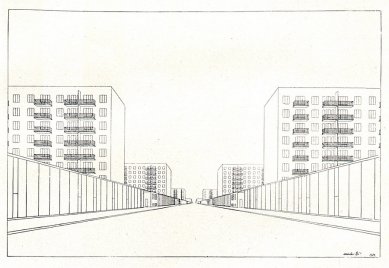

All these areas, of small items, interiors, cities, and landscapes relate to green architecture, called garden or orchard architecture. It begins with a flowerpot on a window or a vase with flowers on a table, continues through gardens and orchards to the entire landscape and larger territorial complexes. In the new architecture of the interior, house, city, and landscape, greenery takes on an unprecedented importance: the greenery of the garden has penetrated into the interiors and all semi-open and open spaces of the contemporary house, whose garden is a continuation of the living rooms; the greenery of the orchards permeates the entire territory of the future city, whose houses and buildings are freely situated in open rows or alone in the midst of orchards; and the greenery of the rural landscape infiltrates new open municipalities, desuburban settlements of the future. An open interior, open building, and open desuburban municipality cannot be imagined without greenery, which becomes an omnipresent element in new architecture, surrounding, permeating, and penetrating everything, a universal substrate upon which all buildings and communication structures and facilities grow.

But greenery is a fundamental element not only for this hypothetical, laboratory architecture of the future. Even the quite concrete modest daily task of improving the current state of our environment can most easily be accomplished by the substantial involvement of vegetation greenery. — If we recognize that reasonable reconstruction and arrangement of apartments, houses, municipalities, and landscapes is the most accessible and entirely real goal of our housing culture in a broad sense, then surely the greenery of plants, complemented by water, is the cheapest and most effective element of such an adjustment.

The greenery of vegetation is an element and material as important as construction materials, as the substance of buildings and other objects and facilities of the environment. It is nothing other than and nothing more or less. The matter of plant greenery is the same and equal matter as the materials of concrete, bricks, plasters, cladding, stone, metals, glass, wood, etc., from which architecture constructs and creates our environment. The difference lies only in the organic nature of the vegetative material, its less precise and certain shape, its higher degree of variability, and the temporal moment of growth and decay. These circumstances must be taken into account. These properties, which at first glance are quite different from those of other solid construction materials, likely support and maintain a widespread misconception, as if garden and orchard architecture were something other than architecture in general and even something that typically trained and educated architects could hardly understand. — Of course, that is not the case and never has been. Just as there is one unified environment, so there is only one architecture that creates, constructs, and plans this entire environment—regardless of what materials and in what temporally variable way: space, volumes, shapes, materials, life functions, and processes—the substantial form and human content of an architectural work are unified throughout architecture.

There is thus no special garden or orchard architecture. Therefore, there cannot be special "garden architects," no matter how seemingly well or poorly specially trained or untrained they may be. The scholarly study of garden, orchard, and landscape architecture should be the same general architectural study that all architects usually complete. At architecture schools, the same, equal, and commensurate information should be provided about plant materials and their use, with the same knowledge and expertise imparted as with all other construction materials and constructions: dendrology, applied botany, scientific horticulture, and even the theory of agricultural plant production for field, meadow, and forestry— from our perspective, are auxiliary sciences of architecture, serving the realization of its projects, just as the sciences of construction materials and constructions serve the same purpose. Dendrological, horticultural, and agricultural experimentation corresponds to similar experimentation in the field of construction materials and constructions, components, and structures. The architect is interested in these sciences and knowledge; he must follow and know the results of relevant experiments and research, but he cannot engage in such a completely different and specialized activity himself; his task is different—wider, general—he is the organizer of all the elements from which the environment arises, the conductor of a multi-member orchestra in which he cannot personally control and play all the instruments and even delve into their production. — After completing a proper architectural school, an architect can engage, for example, in gardens, orchards, and landscape greenery as he might for interiors, residential houses, schools, health, administrative, commercial, industrial, or other buildings, or for urban construction and landscape planning. However, the condition for the level of his work is always a prior proper knowledge of general architecture in all its extent and reach.

This training, along with a just and useful legislative regulation of activities—as in other areas of architecture—is a prerequisite for increased overall architectural quality, even in the realm of private and public green spaces. From the pitiful amateurishness of owners, from the uncultured whims of gardeners and so-called garden architects, from the often helpless so-called artistic care and creation of municipal gardeners and orchard officials in public parks, from the complete lack of protection and care for vegetation in the landscape, it is necessary to reach a high international level of true architecture. — This is the first task, we could say our home Czech task—to raise the level from amateurism, craft, and office to true cultural creation. — The second task would be European and global: to attempt to create a new independent architecture of greenery that is equal in quality and utility to foreign as well as our advanced architecture in other fields—interior, construction, and urban architecture—and at the same time be comparable in significance to historical forms.

If we explore contemporary international architecture, we see that the field and element of vegetation greenery have not yet been understood and architecturally processed anywhere in the world to the extent that is new and harmonious with contemporary and future life of society and individuals and with other areas and fields of new architecture to speak of real new garden, orchard, and landscape architecture, distinct, original, and different from all historical architectures of gardens and orchards, just as the new architecture of cities, buildings, and their interiors differs from historical architectural styles. — The initiators and creators of new architecture abroad and in our country have so far been too occupied with urgent considerations about the foundations and guidelines of new planning for houses and their fittings, cities, and landscapes. — Meanwhile, the free area and organic greenery have become an essential and irreplaceable element. However, this quantitative inclusion of an undeniable substantial amount of free space and greenery into our environment has not yet occurred in a qualitatively new way. The demanded and in many places obtained free and green spaces have not been architecturally shaped sufficiently new and appropriately for new life. American landscape architecture, German Landschaftsgestaltung, the gardens and orchards of new towns and houses, all the unfinished and completed proposals in this area of green architecture—all these works even by the most modern and advanced authors still rely predominantly on historical forms of orchards and gardens—and show only isolated and summary approaches to a new conception; American and German landscape solutions are directly dependent on the historical form of the English landscape; our new orchards, where they are even established, are either mere indistinct plantings of the terrain, architecturally insignificant, or depend forever on the English park with French decoration; meanwhile, both historical forms are banalized, misunderstood, and inorganically connected.

Our gardens, to the extent that they have any architectural value, are based on the patterns of the English park or English flower garden and are the last refuge of decorativism and formalism, rarely reaching a clear character and strict high level achieved in construction architecture, — The English landscape, the English park, and the English flower garden—these are still unsurpassed historical influences, to which is further added the Chinese and Japanese pattern. From these elements, the so-called modern concept of landscape, orchard, and garden architecture is composed. In this concept, abroad and far less so with us, a number of realizations of landscape adjustments, orchards, and gardens have been implemented, more or less quality depending on the personal abilities of the authors and the cultural level of the clients. In France, there are good initiatives of the original new conception, but not extensive, versatile, and systematic enough to give rise to an entire period of new great creation in this field. — If it were allowed to use the old word style in the new architecture in a new non-formalistic sense, one could say that the new style of garden, orchard, and landscape architecture has not yet formed.

One might ask what path this new style could take and what the new concept of green architecture would be. — A new architecture of natural spaces will arise from the needs of human life, just as all historical styles arose from them, which is useful to understand both from an architecturally formal and sociologically content perspective. — From these perspectives, the Italian and French gardens are a lasting architectural lesson on the logical relationship of buildings with terrain and vegetation, a lesson in the regular clear construction of space and forms. From the human content perspective, they are feudal and royal gardens, the noble representative salons of rulers and nobility. — The English park teaches about the free irregular composition of natural spaces and shapes; materially it is a creation and dwelling of the nobility, but of the English, Protestant, sober, and bourgeois modest nobility, thus it becomes a spiritual expression of the bourgeois life of the liberal nineteenth century. It provides individual personalities with solitude and freedom of private movement and residence. — The Chinese and Japanese gardens are formally a lesson in distinctly condensed composition of stylized nature, humanly exemplary in their general nationwide classless character. It is a manifestation of deep, quiet, tender, and intimate love of humanity for nature. — These are succinct general teachings that the historical architecture of gardens and orchards provides, whose architectural form cannot be understood without their human sociological content.

For the new architecture of gardens, orchards, and landscapes, the methodology by which the last great manifestation of vegetative architecture, the English park, arose will be instructive. In the famous English letters of our world-renowned writer, we read: "... I find that what I considered to be England is actually just a great English park: meadows and glades, beautiful trees, century-old alleys, and here and there sheep, just like in Hyde Park, apparently to enhance the impression...". The form of the English park arose from the architectonization of the English landscape, condensing and synthesizing its elements. — Then it is illogical, for example, in the Czech Republic, in the inland Central European landscape of entirely different geographical, ethnographic, and economic nature, that English parks are being established—when the image of foreign nature, grown under other conditions, is mechanically transferred and imitated. It is an uncritical imitation of a foreign pattern, while a critical reassessment is needed. It is not a direct appropriation of form but merely the appropriation of the developmental process from which this form emerged. The English park was formed materially from the English landscape and content-wise from the needs of bourgeois life. — This bourgeois human content was valid in the past century in the entire cultural world, where the bourgeois social class experienced its rise everywhere—therefore, with this generally valid human content, the architectural form of the English park was adopted in the world, since there was no other form.

A new architecture of natural spaces will emerge from a similar process arising from the similar needs of another social class, the working people, whose rise in life is precisely what our twentieth century is experiencing. From the human content perspective, the landscape becomes and will become the home, dwelling, and recreational environment for all social classes, primarily serving the largest population group, to whose civic life the new public orchard and private residential garden will also cater. — This necessity and need to accommodate all people from all social strata in nature is something unprecedented and new and gives a completely new and different sociological human content to the new architecture of greenery.

The architectural form of this new architecture of gardens, orchards, and landscapes will be created—if it arises here—rightfully and entirely logically from the elements of our Czech Central European landscape, from its local native nature and vegetation. Along the way, we will be aware that a whole range of plant elements that we might be inclined to consider typically local and ours come from the most diverse corners of the world, that our nature has changed over the ages and will continue to change, without the danger of losing its own character and identity arising from the soil and climate as well as the nature of the people. — Just as the English park arose from the English landscape, so the new public park could be born from the elements of our Czech landscape. — Keeping this simple foundational idea in mind, we will look anew at our rural environment, the fields, meadows, pastures, groves, forests, trees, rocks, rivers, paths, human dwellings, and gardens of our rural landscapes and municipalities—and we will suddenly see in this familiar, simple, and mundane environment an immense quantity of significant elements and striking forms that we previously did not see or at least did not see as a possible part of the formal and functional repertoire of the new architecture of greenery. The assembly of this surprising, rich, and beautiful material that the Czech landscape provides is the first step toward creating a new formal language, which, with the new form, simultaneously brings new prompts humanly content-wise, and which will emerge from this material through its arrangement, classification, integration into a system, architectural evaluation, variations, permutations, and combinations of elements, providing unlimited magnificent wealth of expression and unlimited possibilities for shaping a new natural living environment—just as several dozen musical notes and instruments offer infinite possibilities for musical creation.

By merging new human popular content and new architectural form derived from the elements of our landscape, a new distinctive architecture of natural spaces may emerge, which can exert its influence directly and indirectly abroad if it is built with quality and conviction and if it genuinely organically merges the universally valid popular element with a new form, also predominantly derived from the civil popular elements of the Czech landscape. Creating a Czech popular architecture of greenery is a task for a multitude of workers for many years and decades. An individual may provide initiative through literary formulating of a new concept and laboratory projects. This path of personal theoretical initiative has often supported and accelerated the emergence and development of historical forms of gardens and parks—Italian and French gardens as well as the English park and American landscapes.

It is necessary to concretely consider further the guidelines that should govern care for gardens, orchards, and landscapes, both to elevate them from the level of craft or office to architectural cultural creation, and to indicate and embark on paths to a new architectural concept in these fields.

For contemporary gardens as living spaces, the same principles of utility and functionality apply as for contemporary apartments. This utility has—like in all other architecture—a dual aspect, material and psychological. Material utility means meeting all physical needs of human dwelling, thus approximately what we simply refer to as a practical and useful solution. Spiritual, psychological utility is what is usually called beauty, pleasant appearance, aesthetic value, tasteful solution, or the pleasantness and kindness of the living space. This functionality and utility, which is simultaneously indivisible into material and spiritual, can also be termed habitability. We say that a living space is more or less habitable, and this residential value will be briefly investigated, analyzed, and it will be shown how and by what it appears in gardens, orchards, and landscapes, and what hinders it in all these natural living spaces.

A residential garden should truly be an extended dwelling, an integral part of the apartment. Let it serve all the needs of unpretentious, simple, and comfortable dwelling, bourgeois and popular: it allows free movement, short walks, comfortable seated and reclining rest on the ground on loungers and chairs, sunbathing, in shade and semi-shade, in wind and shelter, in view and concealment; bathing under the shower or in a water reservoir, sunbathing on the lawn or in a sandpit, good connection with the residential rooms of the house, which transitions into the garden through semi-open spaces of verandas, terraces, balconies, and glazed areas, which provide staying outdoors even in rain and in all seasons and weather conditions and also optically connect the space of the garden with the residential rooms. These amenities, which in their totality and maximum development are undoubtedly accessible only to affluent individuals in expensive private family villas and gardens, are gradually becoming in collective forms of public baths, swimming pools, recreational residences, and people’s parks of leisure the property of broad popular strata. In their simplest and most basic forms, these amenities of simple natural living are available in our times even to relatively less affluent individuals from all social strata. In these modest popular residential gardens, it is clear that the foundation of habitability is always the material reality and the living service: a shower, bathing tank, or at least a good connection of the garden with the bathroom in the house is, for example, incomparably more essential and significant than, say, the usual and seemingly indispensable flower and rose bed, since perfect health and comfort are both simultaneously a psychological and aesthetic value.

The service to the housing needs of man must always and everywhere, for both the poor and the rich, be fulfilled by a simple architectural form, which should be unified, as in every human and natural work, meaning that parts must be mutually linked and subordinated to the whole. This is the secret of every so-called composition both regular and free. Formal architectural logic arises from the precise fulfillment of life functions; the architectural form must be biological, just like in all other architecture. — The civic and popular residential garden—and only that is characteristic of our century—must be materially created from inexpensive and simple elements, its value should rather be of a spiritual nature, residing in good organization and perfect disposition of the living environment, certainly not in rare and expensive plants and materials. It is necessary and possible to achieve the highest necessary comfort and the greatest service to humanity by the least and cheapest means, merely by renouncing a series of usual prejudices. Even in garden architecture applies the well-known saying, translated by Victor Bourgeois, that "the lack of money is the salvation of architecture".

Creating the living space of a garden is the task of designers—it cannot, as in all other architecture, give instructions and prescriptions for how it is done. However, it is possible and necessary to say what a residential garden must not be:

A residential garden must not be a useless representative salon, filled with ornamental decorations of flowers and plants, an uncomfortable outdated space, as exists still today in public parks.

A residential garden cannot be a museum, a repository of plants. Garden enthusiasts tend to this chaotic overcrowding, which results in the garden ultimately lacking any living space. A residential garden cannot be a year-round permanent workplace either. One would hardly live well in an apartment where painting, rearranging furnishings, and cleaning were ongoing. A residential garden must be granted quiet and time for undisturbed free growth. One cannot constantly plow it, for it hardly requires care, as free nature does, which is often very habitable and yet not cared for by anyone.

A residential garden cannot be a vegetable garden or orchard, at least not for those who live there. The necessary amount of vegetables and fruits in any selection can be cheaply purchased at specialized businesses and shops at any time. Fruit trees and bushes tempt theft and destruction. In the garden of a small rural residence, a reasonable level of utility, even keeping small domestic animals, would be in place. However, this need not detract from the habitability and good appearance of such a garden; certainly, its own dwelling will be given proportionately small or smaller space.

The list of prejudices that hinder the emergence of good civic and popular garden architecture continues: even in relatively good gardens, we see many professional and amateur errors and shortcomings. — The lawn is constantly demanded to be perfectly green, fine, dense, and English. However, we should strive for a Czech lawn, a lawn of our mountain pastures, meadows, and fields. — Gardens are needlessly spoiled by so-called professional care of gardeners. Trees are pruned, shrubs are cultivated around their trunks, as if all plants were to grow as much as possible all the time. However, often, it suffices if they grow completely freely, as they wish, just like they grow in the nature of our regions. — Amateurs, gardeners, and so-called "garden architects" believe that something must bloom in the garden all year round. Our simple common shrubs, trees, and plants are still beautiful, even in times when they do not bloom. It is indeed necessary to understand and acknowledge the everyday, mundane, inconspicuous, and simple beauty, its profound, serious, and genuine colorfulness. — The horrible fashion of alpines or rock gardens, considered an indispensable necessity in the so-called modern garden today, is abhorrent. Terraces and stone walls are, however, only appropriate in very sloped terrain, which cannot be otherwise adjusted than with terraces to create a habitable area. In any case, these terraces and walls should be made from a single and local type of stone and should be naturally and unobtrusively overgrown with our completely ordinary plants, typical of the old Czech countryside, such as stonecrop and thyme. — In general, it must be said that a garden does not have and cannot be the so-called "expression of the personality" of its owner and his "taste." From practice we know that owners who talk the most about their personality and taste usually have neither and merely poorly imitate whatever abominable thing they have seen elsewhere or at a neighbor's place. In reality, such gardens often prove to be a manifestation of unculturedness, backwardness, and the owner's mental limitation, which has been painstakingly suppressed and removed from residential homes and apartments through long-term education and promotion, with the last refuge being the wretched garden, thought to withstand any unintelligent whims. In practice, the same applies to the garden project as to the house and apartment: entrust it to a good expert, a good architect, not a "garden" one, nor a gardener or plant trader, who has a single interest in making the best deal by selling the largest quantity of materials and work and imposing the most frequent so-called professional care.

Everything said about the garden fully applies also to the larger dimensions of public orchards of municipalities and cities. Their habitability is collective and personal, they should provide daily recovery for the entire population of all social strata, in large numbers and individuals seeking peace and solitude. The population of cities is rising, and the most populous popular strata have the same right to rest in orchards as other groups of the population. Therefore, sufficient orchard areas are primarily necessary. Popular orchards must be plentiful and large orchards, on whose extensive areas architectural elements borrowed from the landscape can be applied.

Small, overcrowded orchards can never provide good natural living for a large number of people. Insufficient area cannot be compensated for by ancient ornamental floral decorations, nor with establishing expensive and ugly alpines with basalt boulders, nor with cultivating roses and various rare specimens of exotic trees, shrubs, and plants, nor with unnecessary chaotic diversity of vegetation, as is generally done in the Prague orchards. Orchard areas must not be disturbed by communications of any kind—continuity, remoteness, tranquility, silence, and cleanliness of orchards must be protected from the movement, noise, and odors of vehicles. It would be a crime to want to destroy, for instance, even those relatively small continuous orchard areas that history has preserved for us in Prague. A horrific example of such an uncultured act was the projected road or railway into Petřín.

Just as it is a self-evident necessity to protect orchards and their surroundings from traffic chaos, even more so can the criminal bad habit—unnecessary noise of so-called "entertainment" and "popular" music, amplified loudspeakers, whose superhuman roar penetrates even the farthest corners and disrupts the human recovery for which all public orchards are primarily intended—not be allowed. It is foolish to plant expensive floral beds and alpines of dubious beauty and simultaneously allow the daily torture of all visitors and residents living near the orchards through unnecessary and abominable noise. The fulfillment of all human recovery needs in orchards can be achieved, just like in gardens, by simple architectural form and the simple cheap material of our ordinary trees, shrubs, and plants or grasses, used in a few species on large areas with plenty of water, intended for refreshing the eyes, cleaning, and moistening the air, as well as for bathing. — How exactly the new orchards will look is a matter of initiative theoretical projects and their realizations—however, it must be said that the appearance of the new orchards will be fundamentally and completely different from all historical forms, including the English park. From completely ordinary, simple, and everyday elements known from our landscapes, a surprising new whole will emerge, entirely unlike everything currently known in the field of orchard architecture, yet organically fused with our landscape, a whole that is both very old and familiar while also new and surprising.

The habitability of the landscape can mean either the fundamental suitability for human habitation, settlement, and work—deserts and mountain ranges are uninhabitable—or, as in our case, the suitability for residence in nature, natural habitability, which is almost identical with the recreational value of the landscape.

For whom should the landscape be a living space? — It once was for the nobility but only to a limited extent and sense; at the end of the last century, the bourgeoisie came into nature, and our century brings the task of accommodating all people from all social classes in nature. It is about accommodating one's own, both residential and natural, concerning sufficient natural residential areas for recovery, walking, paths, residency, sunbathing, and bathing. Both accommodations, residential and natural, are most easily possible and in an overcrowded country only realizable in a collective manner, which alone can tackle this enormous and new task in a qualitative way. It concerns popular pensions, hotels, sanatoria, health resorts, beaches, habitable banks of rivers and lakes, and artificial swimming pools, concerning mass public transportation that is popularly inexpensive and simple, yet hygienic and convenient. In addition to providing good mass accommodation, which typically suffices for bodily recuperation, it is also necessary to ensure the recovery of nerves and spiritual growth, solitude of the individual in nature, residency in remote, unspoiled, and pristine areas of natural quiet and silence, of which is being catastrophically diminished by the so-called "development." Accommodating immense masses of the populace while simultaneously ensuring untouched calm areas of uninhabited nature is a highly difficult and seemingly unsolvable task, yet all the more urgent and very interesting and compelling for landscape planning. — The only way is a planned economy with the natural and residential values of landscapes that must replace the previous natural growth as soon as possible and on the largest possible scale so that everything that can be saved from natural values can still be salvaged.

This negative aspect, the rescue of the existing values, is currently the most important and urgent task: nothing has happened if the landscape is undeveloped, neglected, as it is often termed "underrated," but clean and unspoiled by any "development" or human activity of any kind. — The residential and recreational value of landscapes can be threatened or destroyed by poor settlement, manufacturing, and transportation.

Settlement that is poorly located, of bad quality and character can be a real disaster. Like a natural disaster, a monstrous development and unrestrained construction frenzy of countless villas, houses, cottages, and shacks has descended upon our lands, through which fertile fields and meadows, beautiful pastures and forests, peaceful valleys and riverbanks are being ruthlessly destroyed with a vandal's thoughtlessness. The entire country is turning into fenced building lots, and the most wretched level of construction activity, like a terrible cancer, is consuming our lands, penetrating surrounding large cities, towns, and municipalities, reaching into the least accessible areas, and will spare not even the most beautiful remote corners of still unspoiled nature. However, it is impossible for the landscape to simultaneously be Stromovka and Hanspaulka, a park and a villa district, or a holiday resort. — However, if it is to be a public natural recreational park, it cannot be overcrowded with hotels, health resorts, and camps—it cannot be simultaneously Stromovka and Špindler’s Mill. — Even public economic mass accommodation has its limits—the residential capacity of landscapes must not be exceeded, unhealthy overcrowding and pollution of nature, the land, air, and water must not occur. The surface of the earth must not become a dump, waters must not become the waste channels and reservoirs of factories and toilets, air must not be destroyed by smoke, smells, and noise of transport, industry, and human settlements, poorly situated.

Another threat to habitability lies in agricultural and industrial production. Agricultural production, field, meadow, and forestry, destroys nature through incorrect rationalization, excessive exploitation, boundless extraction, and the greed of entrepreneurs. Unnecessary draining, water regulation, removes freshness from vegetation, ruins the climate of landscapes and the appearance of natural areas. Fishponds are turning into meadows; pastures, meadows, and forests are turning into fields—and fields, forests, meadows, and pastures are becoming parcels... Forests are being cleared, old alleys, tree rows, groups of trees, and solitary trees and bushes along roads, paths, junctions, dikes of ponds, riverbanks, in fields, meadows, pastures, and on the borders are being cut down. Everything that was better from earlier times is being destroyed, with little being established anew—and when so, it is generally done in a very commercial manner. Beautiful and also useful non-fruit trees will soon become an unknown rarity, if they do not completely perish. Moreover, industrial production damages the habitability of landscapes, especially through poor location and establishment of firms. However, the landscape cannot simultaneously be a recreational park and an industrial district. A deterring example is the old town of Týnec nad Sázavou, where the factory and its residential units destroyed a landscape of significant natural value for the recovery of the Prague population. A similar disaster awaits and has already largely befallen the town of Zruč on the upper Sázava with the construction of Baťa's factory. The construction of the highway, leading through southern Posázaví and the Bohemian-Moravian highlands, is expected to bring "revitalization" to these poor and beautiful regions with new industry and tourism. — In this hope lies a tragic mistake; industry—especially larger industrial firms—cannot be associated with recreational and tourist traffic, for industry will destroy the purity of nature, populate it with new inhabitants, and thereby strip it of values necessary for recreational and tourist landscapes. These examples illustrate the urgency of a landscape plan and legal protection of natural values.

Finally, even transport can degrade the habitability of the landscape if it is poorly managed and dimensioned. The planned routing of the railway through the Šárka Valley and on the slopes of Troja would be an example of such destruction of irreplaceable natural values by railway communications. Fortunately, it was not implemented. — The new road from the municipality of Týnec nad Sázavou to the municipality of Krusičany, leading south towards Konopiště, brutally destroyed the beautiful valley with forests, meadows, and a stream, a place of rare natural purity and peace not far from the capital. — By regulating the Elbe River, the so-called waterway has been established at the cost of the complete destruction of the irreplaceable beauty of the Polabí, which until recently was a magnificent, typically Czech natural park. — The rare strict beauty of the Povltaví, especially in the rocky highlands of Central Bohemia, has been destroyed by unnecessary canalization of the Vltava, from which there will never be, and cannot be, a proper transport route. It seems that there will be no end to this rampage until all Czech rivers, streams, and brooks are transformed into disgusting channels based on the model of the miserable brook Botič. The character of landscapes as well as their habitability are forever marred by these acts of senseless technique, thoughtless and unfeeling. Dozens of kilometers of beautiful habitable riverbanks suitable for swimming and recovery are lost. Czech waterways are transformed into desolate and uninhabitable channels with inhospitable stone embankments.

Unrestrained parceling, thoughtless agriculture, poorly located industry, poorly managed communications—all these human actions become an extremely serious danger to the natural, residential, and recreational value of our landscapes, their cleanliness, unspoiled character, and remoteness. A small country must take care, responsibly and cautiously manage the values of its nature, of which it has no gift more precious than the health of its inhabitants. It is time to establish a club for old Bohemia and Moravia, just as a club for old Prague was once founded. A fiery article should again be written titled "Bestia triumfans" this time, however, it concerns more—it concerns the very essence of our environment, the rescue of our land. The time has come when it is necessary to protect not just individual remarkable objects and areas, Babička's Valley, a thousand-year-old lime tree, and a thousand-year-old yew tree, old castles and mansions, and some natural or botanical reserves, by law. — The entire land, all its landscapes and beauties, especially those daily, mundane, unromantic, and inconspicuous, simple and civic, must be protected before they succumb to complete destruction. There is an immense danger that our landscape, instead of being a dwelling, home, and living and recreational space, will become an unordered, desolate, and filthy repository of people, houses, transport routes, and means—will not be a park of Europe, a garden and orchard, but a monumental dump, where one cannot live due to overcrowding, disorder, noise, and dirt. — A landscape plan is a necessity, care for the order and cleanliness of landscapes is the most urgent necessity—every day new and further damages arise that will one day be expensive and difficult to remedy, if ever they can be compensated for.

The accumulation of space caused by a large part of the population living cramped in large cities is further exacerbated by temporal accumulation: disaster strikes once a week in the form of Sunday. At the same time, the entire population must simultaneously be transported from cities to the countryside for a brief weekend stay. Transport and nature are thus unhealthily overloaded and overcrowded. Similar burdens and overcrowding are caused by holiday breaks and summer and winter vacations. — The economical use of landscapes as living and recreational spaces, as well as the use of all transport and accommodation infrastructures and services, cannot be imagined without a temporal solution to weekly and annual shifts. Every day of the week and every season of the year must be used for residency and recovery, always for a part of the population. This tendency for full utilization and year-round habitability, which is, after all, rising pressure from necessity even under the existing system of weeks and holidays, will lead to a change in vegetative structure—an increased quantity of evergreens, shrubs, and plants in our gardens, orchards, and landscapes, especially in lower altitudes, so that nature remains a consistently habitable space even in the least pleasant weather, not only for habitation but also for pedestrian and vehicular transport.

Landscape planning, systematic care for order and cleanliness in the landscape, and architectural care for landscape greenery could demonstrate that even with relatively significant population density, intensive agriculture, productive industry, and transport, it is possible to preserve and create a highly habitable environment. Denmark has been called a factory for butter. Nevertheless, it is a model natural park, just as our lands can be, if they are protected from bad "development" and cared for. — It has been said that a new park will arise from the elements of the landscape. It must be added that this park will, in turn, act on the character of the landscapes: the park will become a landscape, and the landscape will become a park. If we add that even a good living garden incorporates the local landscape, being an integral component of it, we arrive at a new perfect unity of the natural living environment, a unity that is the hallmark of true culture.

The basis for studying landscape adjustments is a collection of photographs (currently about 6000 images), which contain both negative examples and positive material from which a new system of architecture of gardens, orchards, and landscape greenery emerges. The collection of images was compiled by the author between 1936 and 1939 and later—The article—lecture from the series "For a New Architecture" is a brief and only partial outline of the book "Living Landscape", which is being prepared for publication by Borový Publishing House in Prague.

It is hardly necessary to prove the self-evident fact that free space near our homes and houses, in our villages, cities, and in the open countryside should be living space, that our gardens, orchards, and nature are intended for human habitation, in a broader sense. From this basic understanding arises a series of consequences and requirements. First and foremost, we recognize that the living space of our gardens, orchards, and landscapes is part of a unified living space, the entire environment, whose organization, planning, and shaping is the task of architecture. — Truly contemporary architecture theoretically and practically strives to care for the entire human environment, starting with small items of life and housing needs, various tools, dishes, cutlery, housing components, and accessories (industrial and so-called decorative arts projects) through interior furnishings, furniture, installation items (interior architecture) to building projects of all kinds and sizes (building architecture)—and from there to large construction complexes, municipalities, and their parts (urban development)—and finally to the entire territory, landscaping, and planning (regionalism).

All these areas, of small items, interiors, cities, and landscapes relate to green architecture, called garden or orchard architecture. It begins with a flowerpot on a window or a vase with flowers on a table, continues through gardens and orchards to the entire landscape and larger territorial complexes. In the new architecture of the interior, house, city, and landscape, greenery takes on an unprecedented importance: the greenery of the garden has penetrated into the interiors and all semi-open and open spaces of the contemporary house, whose garden is a continuation of the living rooms; the greenery of the orchards permeates the entire territory of the future city, whose houses and buildings are freely situated in open rows or alone in the midst of orchards; and the greenery of the rural landscape infiltrates new open municipalities, desuburban settlements of the future. An open interior, open building, and open desuburban municipality cannot be imagined without greenery, which becomes an omnipresent element in new architecture, surrounding, permeating, and penetrating everything, a universal substrate upon which all buildings and communication structures and facilities grow.

But greenery is a fundamental element not only for this hypothetical, laboratory architecture of the future. Even the quite concrete modest daily task of improving the current state of our environment can most easily be accomplished by the substantial involvement of vegetation greenery. — If we recognize that reasonable reconstruction and arrangement of apartments, houses, municipalities, and landscapes is the most accessible and entirely real goal of our housing culture in a broad sense, then surely the greenery of plants, complemented by water, is the cheapest and most effective element of such an adjustment.

The greenery of vegetation is an element and material as important as construction materials, as the substance of buildings and other objects and facilities of the environment. It is nothing other than and nothing more or less. The matter of plant greenery is the same and equal matter as the materials of concrete, bricks, plasters, cladding, stone, metals, glass, wood, etc., from which architecture constructs and creates our environment. The difference lies only in the organic nature of the vegetative material, its less precise and certain shape, its higher degree of variability, and the temporal moment of growth and decay. These circumstances must be taken into account. These properties, which at first glance are quite different from those of other solid construction materials, likely support and maintain a widespread misconception, as if garden and orchard architecture were something other than architecture in general and even something that typically trained and educated architects could hardly understand. — Of course, that is not the case and never has been. Just as there is one unified environment, so there is only one architecture that creates, constructs, and plans this entire environment—regardless of what materials and in what temporally variable way: space, volumes, shapes, materials, life functions, and processes—the substantial form and human content of an architectural work are unified throughout architecture.

There is thus no special garden or orchard architecture. Therefore, there cannot be special "garden architects," no matter how seemingly well or poorly specially trained or untrained they may be. The scholarly study of garden, orchard, and landscape architecture should be the same general architectural study that all architects usually complete. At architecture schools, the same, equal, and commensurate information should be provided about plant materials and their use, with the same knowledge and expertise imparted as with all other construction materials and constructions: dendrology, applied botany, scientific horticulture, and even the theory of agricultural plant production for field, meadow, and forestry— from our perspective, are auxiliary sciences of architecture, serving the realization of its projects, just as the sciences of construction materials and constructions serve the same purpose. Dendrological, horticultural, and agricultural experimentation corresponds to similar experimentation in the field of construction materials and constructions, components, and structures. The architect is interested in these sciences and knowledge; he must follow and know the results of relevant experiments and research, but he cannot engage in such a completely different and specialized activity himself; his task is different—wider, general—he is the organizer of all the elements from which the environment arises, the conductor of a multi-member orchestra in which he cannot personally control and play all the instruments and even delve into their production. — After completing a proper architectural school, an architect can engage, for example, in gardens, orchards, and landscape greenery as he might for interiors, residential houses, schools, health, administrative, commercial, industrial, or other buildings, or for urban construction and landscape planning. However, the condition for the level of his work is always a prior proper knowledge of general architecture in all its extent and reach.

This training, along with a just and useful legislative regulation of activities—as in other areas of architecture—is a prerequisite for increased overall architectural quality, even in the realm of private and public green spaces. From the pitiful amateurishness of owners, from the uncultured whims of gardeners and so-called garden architects, from the often helpless so-called artistic care and creation of municipal gardeners and orchard officials in public parks, from the complete lack of protection and care for vegetation in the landscape, it is necessary to reach a high international level of true architecture. — This is the first task, we could say our home Czech task—to raise the level from amateurism, craft, and office to true cultural creation. — The second task would be European and global: to attempt to create a new independent architecture of greenery that is equal in quality and utility to foreign as well as our advanced architecture in other fields—interior, construction, and urban architecture—and at the same time be comparable in significance to historical forms.

If we explore contemporary international architecture, we see that the field and element of vegetation greenery have not yet been understood and architecturally processed anywhere in the world to the extent that is new and harmonious with contemporary and future life of society and individuals and with other areas and fields of new architecture to speak of real new garden, orchard, and landscape architecture, distinct, original, and different from all historical architectures of gardens and orchards, just as the new architecture of cities, buildings, and their interiors differs from historical architectural styles. — The initiators and creators of new architecture abroad and in our country have so far been too occupied with urgent considerations about the foundations and guidelines of new planning for houses and their fittings, cities, and landscapes. — Meanwhile, the free area and organic greenery have become an essential and irreplaceable element. However, this quantitative inclusion of an undeniable substantial amount of free space and greenery into our environment has not yet occurred in a qualitatively new way. The demanded and in many places obtained free and green spaces have not been architecturally shaped sufficiently new and appropriately for new life. American landscape architecture, German Landschaftsgestaltung, the gardens and orchards of new towns and houses, all the unfinished and completed proposals in this area of green architecture—all these works even by the most modern and advanced authors still rely predominantly on historical forms of orchards and gardens—and show only isolated and summary approaches to a new conception; American and German landscape solutions are directly dependent on the historical form of the English landscape; our new orchards, where they are even established, are either mere indistinct plantings of the terrain, architecturally insignificant, or depend forever on the English park with French decoration; meanwhile, both historical forms are banalized, misunderstood, and inorganically connected.

Our gardens, to the extent that they have any architectural value, are based on the patterns of the English park or English flower garden and are the last refuge of decorativism and formalism, rarely reaching a clear character and strict high level achieved in construction architecture, — The English landscape, the English park, and the English flower garden—these are still unsurpassed historical influences, to which is further added the Chinese and Japanese pattern. From these elements, the so-called modern concept of landscape, orchard, and garden architecture is composed. In this concept, abroad and far less so with us, a number of realizations of landscape adjustments, orchards, and gardens have been implemented, more or less quality depending on the personal abilities of the authors and the cultural level of the clients. In France, there are good initiatives of the original new conception, but not extensive, versatile, and systematic enough to give rise to an entire period of new great creation in this field. — If it were allowed to use the old word style in the new architecture in a new non-formalistic sense, one could say that the new style of garden, orchard, and landscape architecture has not yet formed.

One might ask what path this new style could take and what the new concept of green architecture would be. — A new architecture of natural spaces will arise from the needs of human life, just as all historical styles arose from them, which is useful to understand both from an architecturally formal and sociologically content perspective. — From these perspectives, the Italian and French gardens are a lasting architectural lesson on the logical relationship of buildings with terrain and vegetation, a lesson in the regular clear construction of space and forms. From the human content perspective, they are feudal and royal gardens, the noble representative salons of rulers and nobility. — The English park teaches about the free irregular composition of natural spaces and shapes; materially it is a creation and dwelling of the nobility, but of the English, Protestant, sober, and bourgeois modest nobility, thus it becomes a spiritual expression of the bourgeois life of the liberal nineteenth century. It provides individual personalities with solitude and freedom of private movement and residence. — The Chinese and Japanese gardens are formally a lesson in distinctly condensed composition of stylized nature, humanly exemplary in their general nationwide classless character. It is a manifestation of deep, quiet, tender, and intimate love of humanity for nature. — These are succinct general teachings that the historical architecture of gardens and orchards provides, whose architectural form cannot be understood without their human sociological content.

For the new architecture of gardens, orchards, and landscapes, the methodology by which the last great manifestation of vegetative architecture, the English park, arose will be instructive. In the famous English letters of our world-renowned writer, we read: "... I find that what I considered to be England is actually just a great English park: meadows and glades, beautiful trees, century-old alleys, and here and there sheep, just like in Hyde Park, apparently to enhance the impression...". The form of the English park arose from the architectonization of the English landscape, condensing and synthesizing its elements. — Then it is illogical, for example, in the Czech Republic, in the inland Central European landscape of entirely different geographical, ethnographic, and economic nature, that English parks are being established—when the image of foreign nature, grown under other conditions, is mechanically transferred and imitated. It is an uncritical imitation of a foreign pattern, while a critical reassessment is needed. It is not a direct appropriation of form but merely the appropriation of the developmental process from which this form emerged. The English park was formed materially from the English landscape and content-wise from the needs of bourgeois life. — This bourgeois human content was valid in the past century in the entire cultural world, where the bourgeois social class experienced its rise everywhere—therefore, with this generally valid human content, the architectural form of the English park was adopted in the world, since there was no other form.

A new architecture of natural spaces will emerge from a similar process arising from the similar needs of another social class, the working people, whose rise in life is precisely what our twentieth century is experiencing. From the human content perspective, the landscape becomes and will become the home, dwelling, and recreational environment for all social classes, primarily serving the largest population group, to whose civic life the new public orchard and private residential garden will also cater. — This necessity and need to accommodate all people from all social strata in nature is something unprecedented and new and gives a completely new and different sociological human content to the new architecture of greenery.

The architectural form of this new architecture of gardens, orchards, and landscapes will be created—if it arises here—rightfully and entirely logically from the elements of our Czech Central European landscape, from its local native nature and vegetation. Along the way, we will be aware that a whole range of plant elements that we might be inclined to consider typically local and ours come from the most diverse corners of the world, that our nature has changed over the ages and will continue to change, without the danger of losing its own character and identity arising from the soil and climate as well as the nature of the people. — Just as the English park arose from the English landscape, so the new public park could be born from the elements of our Czech landscape. — Keeping this simple foundational idea in mind, we will look anew at our rural environment, the fields, meadows, pastures, groves, forests, trees, rocks, rivers, paths, human dwellings, and gardens of our rural landscapes and municipalities—and we will suddenly see in this familiar, simple, and mundane environment an immense quantity of significant elements and striking forms that we previously did not see or at least did not see as a possible part of the formal and functional repertoire of the new architecture of greenery. The assembly of this surprising, rich, and beautiful material that the Czech landscape provides is the first step toward creating a new formal language, which, with the new form, simultaneously brings new prompts humanly content-wise, and which will emerge from this material through its arrangement, classification, integration into a system, architectural evaluation, variations, permutations, and combinations of elements, providing unlimited magnificent wealth of expression and unlimited possibilities for shaping a new natural living environment—just as several dozen musical notes and instruments offer infinite possibilities for musical creation.

By merging new human popular content and new architectural form derived from the elements of our landscape, a new distinctive architecture of natural spaces may emerge, which can exert its influence directly and indirectly abroad if it is built with quality and conviction and if it genuinely organically merges the universally valid popular element with a new form, also predominantly derived from the civil popular elements of the Czech landscape. Creating a Czech popular architecture of greenery is a task for a multitude of workers for many years and decades. An individual may provide initiative through literary formulating of a new concept and laboratory projects. This path of personal theoretical initiative has often supported and accelerated the emergence and development of historical forms of gardens and parks—Italian and French gardens as well as the English park and American landscapes.

It is necessary to concretely consider further the guidelines that should govern care for gardens, orchards, and landscapes, both to elevate them from the level of craft or office to architectural cultural creation, and to indicate and embark on paths to a new architectural concept in these fields.

For contemporary gardens as living spaces, the same principles of utility and functionality apply as for contemporary apartments. This utility has—like in all other architecture—a dual aspect, material and psychological. Material utility means meeting all physical needs of human dwelling, thus approximately what we simply refer to as a practical and useful solution. Spiritual, psychological utility is what is usually called beauty, pleasant appearance, aesthetic value, tasteful solution, or the pleasantness and kindness of the living space. This functionality and utility, which is simultaneously indivisible into material and spiritual, can also be termed habitability. We say that a living space is more or less habitable, and this residential value will be briefly investigated, analyzed, and it will be shown how and by what it appears in gardens, orchards, and landscapes, and what hinders it in all these natural living spaces.

A residential garden should truly be an extended dwelling, an integral part of the apartment. Let it serve all the needs of unpretentious, simple, and comfortable dwelling, bourgeois and popular: it allows free movement, short walks, comfortable seated and reclining rest on the ground on loungers and chairs, sunbathing, in shade and semi-shade, in wind and shelter, in view and concealment; bathing under the shower or in a water reservoir, sunbathing on the lawn or in a sandpit, good connection with the residential rooms of the house, which transitions into the garden through semi-open spaces of verandas, terraces, balconies, and glazed areas, which provide staying outdoors even in rain and in all seasons and weather conditions and also optically connect the space of the garden with the residential rooms. These amenities, which in their totality and maximum development are undoubtedly accessible only to affluent individuals in expensive private family villas and gardens, are gradually becoming in collective forms of public baths, swimming pools, recreational residences, and people’s parks of leisure the property of broad popular strata. In their simplest and most basic forms, these amenities of simple natural living are available in our times even to relatively less affluent individuals from all social strata. In these modest popular residential gardens, it is clear that the foundation of habitability is always the material reality and the living service: a shower, bathing tank, or at least a good connection of the garden with the bathroom in the house is, for example, incomparably more essential and significant than, say, the usual and seemingly indispensable flower and rose bed, since perfect health and comfort are both simultaneously a psychological and aesthetic value.

The service to the housing needs of man must always and everywhere, for both the poor and the rich, be fulfilled by a simple architectural form, which should be unified, as in every human and natural work, meaning that parts must be mutually linked and subordinated to the whole. This is the secret of every so-called composition both regular and free. Formal architectural logic arises from the precise fulfillment of life functions; the architectural form must be biological, just like in all other architecture. — The civic and popular residential garden—and only that is characteristic of our century—must be materially created from inexpensive and simple elements, its value should rather be of a spiritual nature, residing in good organization and perfect disposition of the living environment, certainly not in rare and expensive plants and materials. It is necessary and possible to achieve the highest necessary comfort and the greatest service to humanity by the least and cheapest means, merely by renouncing a series of usual prejudices. Even in garden architecture applies the well-known saying, translated by Victor Bourgeois, that "the lack of money is the salvation of architecture".

Creating the living space of a garden is the task of designers—it cannot, as in all other architecture, give instructions and prescriptions for how it is done. However, it is possible and necessary to say what a residential garden must not be:

A residential garden must not be a useless representative salon, filled with ornamental decorations of flowers and plants, an uncomfortable outdated space, as exists still today in public parks.

A residential garden cannot be a museum, a repository of plants. Garden enthusiasts tend to this chaotic overcrowding, which results in the garden ultimately lacking any living space. A residential garden cannot be a year-round permanent workplace either. One would hardly live well in an apartment where painting, rearranging furnishings, and cleaning were ongoing. A residential garden must be granted quiet and time for undisturbed free growth. One cannot constantly plow it, for it hardly requires care, as free nature does, which is often very habitable and yet not cared for by anyone.

A residential garden cannot be a vegetable garden or orchard, at least not for those who live there. The necessary amount of vegetables and fruits in any selection can be cheaply purchased at specialized businesses and shops at any time. Fruit trees and bushes tempt theft and destruction. In the garden of a small rural residence, a reasonable level of utility, even keeping small domestic animals, would be in place. However, this need not detract from the habitability and good appearance of such a garden; certainly, its own dwelling will be given proportionately small or smaller space.

The list of prejudices that hinder the emergence of good civic and popular garden architecture continues: even in relatively good gardens, we see many professional and amateur errors and shortcomings. — The lawn is constantly demanded to be perfectly green, fine, dense, and English. However, we should strive for a Czech lawn, a lawn of our mountain pastures, meadows, and fields. — Gardens are needlessly spoiled by so-called professional care of gardeners. Trees are pruned, shrubs are cultivated around their trunks, as if all plants were to grow as much as possible all the time. However, often, it suffices if they grow completely freely, as they wish, just like they grow in the nature of our regions. — Amateurs, gardeners, and so-called "garden architects" believe that something must bloom in the garden all year round. Our simple common shrubs, trees, and plants are still beautiful, even in times when they do not bloom. It is indeed necessary to understand and acknowledge the everyday, mundane, inconspicuous, and simple beauty, its profound, serious, and genuine colorfulness. — The horrible fashion of alpines or rock gardens, considered an indispensable necessity in the so-called modern garden today, is abhorrent. Terraces and stone walls are, however, only appropriate in very sloped terrain, which cannot be otherwise adjusted than with terraces to create a habitable area. In any case, these terraces and walls should be made from a single and local type of stone and should be naturally and unobtrusively overgrown with our completely ordinary plants, typical of the old Czech countryside, such as stonecrop and thyme. — In general, it must be said that a garden does not have and cannot be the so-called "expression of the personality" of its owner and his "taste." From practice we know that owners who talk the most about their personality and taste usually have neither and merely poorly imitate whatever abominable thing they have seen elsewhere or at a neighbor's place. In reality, such gardens often prove to be a manifestation of unculturedness, backwardness, and the owner's mental limitation, which has been painstakingly suppressed and removed from residential homes and apartments through long-term education and promotion, with the last refuge being the wretched garden, thought to withstand any unintelligent whims. In practice, the same applies to the garden project as to the house and apartment: entrust it to a good expert, a good architect, not a "garden" one, nor a gardener or plant trader, who has a single interest in making the best deal by selling the largest quantity of materials and work and imposing the most frequent so-called professional care.

Everything said about the garden fully applies also to the larger dimensions of public orchards of municipalities and cities. Their habitability is collective and personal, they should provide daily recovery for the entire population of all social strata, in large numbers and individuals seeking peace and solitude. The population of cities is rising, and the most populous popular strata have the same right to rest in orchards as other groups of the population. Therefore, sufficient orchard areas are primarily necessary. Popular orchards must be plentiful and large orchards, on whose extensive areas architectural elements borrowed from the landscape can be applied.

Small, overcrowded orchards can never provide good natural living for a large number of people. Insufficient area cannot be compensated for by ancient ornamental floral decorations, nor with establishing expensive and ugly alpines with basalt boulders, nor with cultivating roses and various rare specimens of exotic trees, shrubs, and plants, nor with unnecessary chaotic diversity of vegetation, as is generally done in the Prague orchards. Orchard areas must not be disturbed by communications of any kind—continuity, remoteness, tranquility, silence, and cleanliness of orchards must be protected from the movement, noise, and odors of vehicles. It would be a crime to want to destroy, for instance, even those relatively small continuous orchard areas that history has preserved for us in Prague. A horrific example of such an uncultured act was the projected road or railway into Petřín.

Just as it is a self-evident necessity to protect orchards and their surroundings from traffic chaos, even more so can the criminal bad habit—unnecessary noise of so-called "entertainment" and "popular" music, amplified loudspeakers, whose superhuman roar penetrates even the farthest corners and disrupts the human recovery for which all public orchards are primarily intended—not be allowed. It is foolish to plant expensive floral beds and alpines of dubious beauty and simultaneously allow the daily torture of all visitors and residents living near the orchards through unnecessary and abominable noise. The fulfillment of all human recovery needs in orchards can be achieved, just like in gardens, by simple architectural form and the simple cheap material of our ordinary trees, shrubs, and plants or grasses, used in a few species on large areas with plenty of water, intended for refreshing the eyes, cleaning, and moistening the air, as well as for bathing. — How exactly the new orchards will look is a matter of initiative theoretical projects and their realizations—however, it must be said that the appearance of the new orchards will be fundamentally and completely different from all historical forms, including the English park. From completely ordinary, simple, and everyday elements known from our landscapes, a surprising new whole will emerge, entirely unlike everything currently known in the field of orchard architecture, yet organically fused with our landscape, a whole that is both very old and familiar while also new and surprising.

The habitability of the landscape can mean either the fundamental suitability for human habitation, settlement, and work—deserts and mountain ranges are uninhabitable—or, as in our case, the suitability for residence in nature, natural habitability, which is almost identical with the recreational value of the landscape.

For whom should the landscape be a living space? — It once was for the nobility but only to a limited extent and sense; at the end of the last century, the bourgeoisie came into nature, and our century brings the task of accommodating all people from all social classes in nature. It is about accommodating one's own, both residential and natural, concerning sufficient natural residential areas for recovery, walking, paths, residency, sunbathing, and bathing. Both accommodations, residential and natural, are most easily possible and in an overcrowded country only realizable in a collective manner, which alone can tackle this enormous and new task in a qualitative way. It concerns popular pensions, hotels, sanatoria, health resorts, beaches, habitable banks of rivers and lakes, and artificial swimming pools, concerning mass public transportation that is popularly inexpensive and simple, yet hygienic and convenient. In addition to providing good mass accommodation, which typically suffices for bodily recuperation, it is also necessary to ensure the recovery of nerves and spiritual growth, solitude of the individual in nature, residency in remote, unspoiled, and pristine areas of natural quiet and silence, of which is being catastrophically diminished by the so-called "development." Accommodating immense masses of the populace while simultaneously ensuring untouched calm areas of uninhabited nature is a highly difficult and seemingly unsolvable task, yet all the more urgent and very interesting and compelling for landscape planning. — The only way is a planned economy with the natural and residential values of landscapes that must replace the previous natural growth as soon as possible and on the largest possible scale so that everything that can be saved from natural values can still be salvaged.

This negative aspect, the rescue of the existing values, is currently the most important and urgent task: nothing has happened if the landscape is undeveloped, neglected, as it is often termed "underrated," but clean and unspoiled by any "development" or human activity of any kind. — The residential and recreational value of landscapes can be threatened or destroyed by poor settlement, manufacturing, and transportation.

Settlement that is poorly located, of bad quality and character can be a real disaster. Like a natural disaster, a monstrous development and unrestrained construction frenzy of countless villas, houses, cottages, and shacks has descended upon our lands, through which fertile fields and meadows, beautiful pastures and forests, peaceful valleys and riverbanks are being ruthlessly destroyed with a vandal's thoughtlessness. The entire country is turning into fenced building lots, and the most wretched level of construction activity, like a terrible cancer, is consuming our lands, penetrating surrounding large cities, towns, and municipalities, reaching into the least accessible areas, and will spare not even the most beautiful remote corners of still unspoiled nature. However, it is impossible for the landscape to simultaneously be Stromovka and Hanspaulka, a park and a villa district, or a holiday resort. — However, if it is to be a public natural recreational park, it cannot be overcrowded with hotels, health resorts, and camps—it cannot be simultaneously Stromovka and Špindler’s Mill. — Even public economic mass accommodation has its limits—the residential capacity of landscapes must not be exceeded, unhealthy overcrowding and pollution of nature, the land, air, and water must not occur. The surface of the earth must not become a dump, waters must not become the waste channels and reservoirs of factories and toilets, air must not be destroyed by smoke, smells, and noise of transport, industry, and human settlements, poorly situated.

Another threat to habitability lies in agricultural and industrial production. Agricultural production, field, meadow, and forestry, destroys nature through incorrect rationalization, excessive exploitation, boundless extraction, and the greed of entrepreneurs. Unnecessary draining, water regulation, removes freshness from vegetation, ruins the climate of landscapes and the appearance of natural areas. Fishponds are turning into meadows; pastures, meadows, and forests are turning into fields—and fields, forests, meadows, and pastures are becoming parcels... Forests are being cleared, old alleys, tree rows, groups of trees, and solitary trees and bushes along roads, paths, junctions, dikes of ponds, riverbanks, in fields, meadows, pastures, and on the borders are being cut down. Everything that was better from earlier times is being destroyed, with little being established anew—and when so, it is generally done in a very commercial manner. Beautiful and also useful non-fruit trees will soon become an unknown rarity, if they do not completely perish. Moreover, industrial production damages the habitability of landscapes, especially through poor location and establishment of firms. However, the landscape cannot simultaneously be a recreational park and an industrial district. A deterring example is the old town of Týnec nad Sázavou, where the factory and its residential units destroyed a landscape of significant natural value for the recovery of the Prague population. A similar disaster awaits and has already largely befallen the town of Zruč on the upper Sázava with the construction of Baťa's factory. The construction of the highway, leading through southern Posázaví and the Bohemian-Moravian highlands, is expected to bring "revitalization" to these poor and beautiful regions with new industry and tourism. — In this hope lies a tragic mistake; industry—especially larger industrial firms—cannot be associated with recreational and tourist traffic, for industry will destroy the purity of nature, populate it with new inhabitants, and thereby strip it of values necessary for recreational and tourist landscapes. These examples illustrate the urgency of a landscape plan and legal protection of natural values.