Whitney Museum of American Art

|

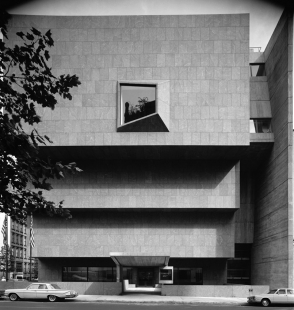

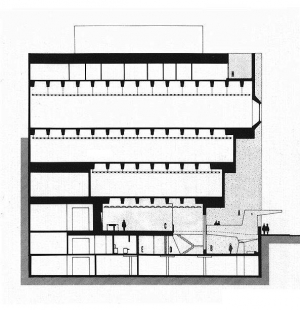

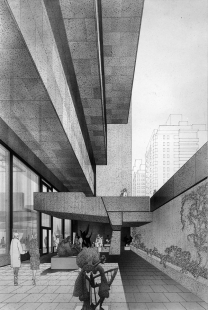

It is easier to say first what it should not look like. It should not look like a business or office building, nor should it look like a place of light entertainment. Its form and its material should have identity and weight in the neighborhood of 50-story skyscrapers, of mile long bridges, in the midst of the dynamic jungle of our colorful city. It should be an independent and self- relying unit, exposed to history, and at the same time it should transform the vitality of the street into the sincerity and profundity of art."

Marcel Breuer

The Whitney Museum's home stands defiantly apart from identifiable trends of twentieth-century New York architecture, and has accordingly not aged since its opening in the fall of 1966. At the time, the vertiginous International Style glass towers rising in midtown seemed in sync both with the futuristic optimism of the recent 1964 New York World's Fair, and with the sameness of "the organization man" pilloried by William Hollingsworth Whyte in his 1956 book of that title. The Whitney's blocky new building stood the status quo on its head, using the vernacular of Mesopotamian antiquity―the ziggurat― to question the received architectural wisdom of the contemporary era. It still does. Not out of spite or ridicule, but out of a questioning spirit―that quintessentially American trait that rejects conformity for its own sake.

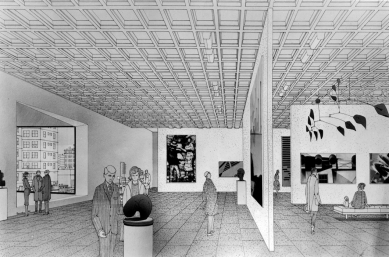

When it opened, the building had a formidable resonance for me, a young Manhattanite with a rebellious nature. Decades later, entering the Whitney I find the architectural experience as rewarding as it was on my first visit, because the Breuer building is brilliantly flexible in it galleries, elegant beyond compare in its spare granite, concrete, and slate palette, and oddly severe but playful in its visual metaphors. While other twentieth-century museum buildings in New York may stray toward the quirky or the generic, the Whitney winks through its polygonal windows at passersby, seduces them to enter, and rewards each visitor with its ageless simplicity. Those of us privileged enough to work in it endure its modest size but revel in its boldness and its integrity in the face of fleeting fashion.

Maxwell L. Anderson, former director, Whitney Museum of American Art

0 comments

add comment