Entrance hall and check-in building of the Main Train Station in Prague

The method of reconstructing the Prague railway hub, including the closure of the stations in Bubny, Těšnov, and Prague-center, and the concentration of passenger transport at the main station, was determined by government resolution no. 928 in 1960, based on the prospective study of the State Institute of Transport Planning (SÚDOP). Architect Josef Danda, however, had been dealing with the solution of the central Prague station, combined with a metro station and a bus station, at least since 1947, when he wrote a dissertation on it. During the 1960s, he created or participated in a number of studies, in which almost all operational and spatial solutions of the final concept gradually appeared, which can be dated to 1967.(1) The pre-war main north-south corridor (2) was then given a place between the tracks and Opletalova street, although as late as 1966 a large competition for the “central station” preferred its alignment over the tracks, along the viaduct.(3) The already commenced construction of the underground tramway was again and definitively changed to a metro along the same route. The sum of the existing capacities of the closing stations and the predicted increase in traffic determined that the main station must handle 210,000 passengers daily – or also 20,000 in peak hours.(4) What entered the planning as completely new at that time was the acknowledgment of the value of the existing terminal building, which was then referred to as the Fantova building.(5) The decision to preserve “the most remarkable of Prague's Art Nouveau architectures”(6) contributed to the choice of the concept of terminal hall developing by Danda,(7) which also meant a significant entry into Vrchlicky Gardens. Therefore, in 1970, the Ministry of Transport, in collaboration with the Union of Architects, announced a limited competition for its “architectural and artistic resolution”,(8) in which the proposal by Jan Bočan, Jan Šrámek, and Alena Šrámková won.(9) However, their intention to sink the hall as much as possible into the ground would have meant its clear height of only four meters (compared to the existing seven), and the ministry therefore requested the preservation of Josef Danda's solution, who thus, along with another architect from SÚDOP, Júlie Trnková, became part of the design team.(10)

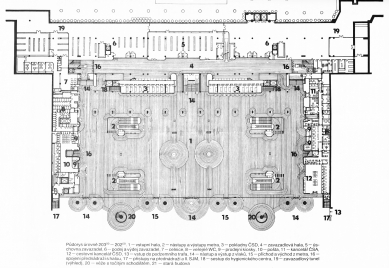

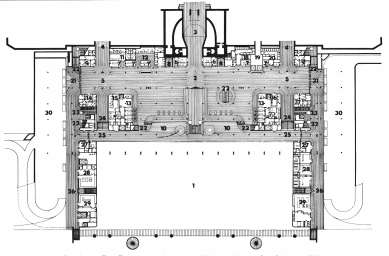

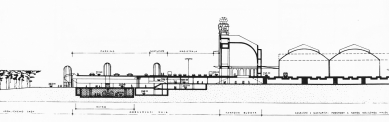

Danda conceived the station in three operational parts. The entrance hall (5,600 m²) was intended for pedestrian visitors and metro passengers (80%), utilizing shops and services along its sides. Since it could not load the metro tubes and at the same time bear the forecourt parking lot, it is composed of a steel bridge structure: 33 welded I-beams, which are only 60 cm high at a span of 45.5 meters and form a single dilatational unit measuring 145 × 45.5 meters, resting on pot neoprene bearings and weighing 2,063 tons.(11) The generous free space of the hall smoothly connected to the ground floor of the three-story terminal building (4,500 m²), and was organized by a transverse row of ticket counters, behind which was situated the area for receiving and storing luggage. The floor was designed for passengers who arrived at the station by their own vehicles, taxis, or buses (20%), for which the aforementioned parking on the roof of the entrance hall served, and along with other ticketing and services, it primarily formed a waiting room on the open gallery. The terminal building consists of a reinforced concrete skeleton in a nine-meter module; the steel columns of the last floor support its ceiling, bearing the roadway of the corridor. This too is designed as a smoothly supported unit without expansion joints – a reinforced concrete cassette slab with ribs every meter is 65 cm high at dimensions of 145 × 46.5 m.(12) Finally, the third operational part, including a restaurant, shops, and long-term waiting areas, was to consist of the original Fantova building, operationally connected and reconstructed according to a special project by Danda in cooperation with Zdeněk Vávra and František Flašar from the State Institute for the Reconstruction of Monumental Towns and Objects, which was later taken over by Jarmila Růzhová-Janáčková, but which had not been completed until recently. Just the fact that the roadway of the corridor ultimately ended up more than half a meter above the base of its façade contributed to the fact that the building then became a “monstrous fragment”.(13)

Architecturally managing such a primarily transport-related, extraordinarily extensive, and additionally underground construction was not an easy task. The team of Jan Šrámek, Alena Šrámková, and Jan Bočan, whose project was temporarily replaced by Zdeněk Rothbauer, managed to cultivate its straightforward, modernist spatial concept with inventive detail – creating an interior on a scale with the exterior.(14) At the level of the floor plan, they utilized a rigorous grouping of functional units into blocks with rounded corners, which, applied equally carefully in sections, create fabion transitions between the floor and the wall, and in more complex places of joints, distinctive sculptural formations. Rostislav Švácha considers this approach, from graphic to spatial, characteristic of the collaboration between Jan Šrámek on one side, and Jan Bočan with Zdeněk Rothbauer on the other, in works on exactly the opposite end of the typological spectrum, namely the representative interiors of diplomatic offices, whether designed by Karel Filsak, or by the authors themselves, as was the case with the embassy in London, for which they received the Royal Institute of British Architects Award in 1970.(16) Among the characteristic features of that historical period is that Šrámek’s “even over-cultivated harmonies of color and shape”(16) resonated in the station hall, which, completely in line with its transportation purpose, also utilized a glaring signal red. With it, the architects drew into their game its extraordinary constructions and technical installations: the cassette shape of the concrete ceiling slab is projected onto its cladding, the steel beam became the main motive of the only façade, while the beams fade into the shadows behind the luminaires, suspended at the level of their bottom flange, from which emerge again the red ducts of the air conditioning. Such “emphasis on the technical properties of construction components”(17) is closely related to the contemporaneously designed and completed Parisian icon of the technocratic style, later dubbed “high-tech.” Somewhere on the border of the artistic and industrial stands the streamlined patterns of the paving, which, according to her own words, “expanded upon” by Alena Šrámková, as well as the stainless steel frames of cashier booths and doors. The glazed stair towers in front of the façade and on the roof of the hall were originally to be casings for the colorfully glowing glass sculptures of Stanislav Libenský.

The realization of the work, “essentially identical with the intentions of the project”,(18) progressed rapidly for its time. Construction began in 1972 with the piloting of the foundations; the steel constructions of the entrance hall were manufactured and assembled by the Vítkovice Ironworks in 1973, the cassette ceiling of the terminal building was completed by Metrostav in 1974, and in September 1976, the first passengers began passing through the southern part of the entrance hall. After the ceremonial opening of the entire station on July 1, 1977(19), a least the glazing of the towers and the completion of the ramp leading to the forecourt followed in 1978, and in the following year, the park modifications, on which the Šrámek couple collaborated with Otakar Kuča in their first proposal in 1977.(20)

Notes:

1) Karel Hájek, Architect Josef Danda, Prague 2007, pp. 143–171.

2) Jiří Novotný, One Hundred Years of the Prague North-South Corridor, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXI, 1962, no. 5, pp. 292.

3) Milan Procházka, On the Competition for the Central Station in Prague, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXVI, 1967, no. 1, pp. 10–17.

4) Jaromír Seidl, A Station for 210,000 Passengers, Railroad Worker I (XVII), 1967, no. 26, p. [1].

5) In 1963, Emanuel Poche rehabilitated it in his popular guide, who also prepared the architectural part of the successful exhibition at Hluboká Castle in 1966. Emanuel Poche, Prague Step by Step: A Guide to the City, Prague 1963; Jiří Kotalík (ed.), Czech Art Nouveau: Art 1900. Exhibition Catalog: Alšova South Bohemian Gallery – National Gallery in Prague – Academy of Fine Arts 1966.

6) Oldřich Dostál – Věra Konečná, Prague Art Nouveau, in: Zdislav Buříval (ed.), Centennial Prague II, 1966, pp. 80–101, here p. 91.

7) Compare: Miloš Pistorius, Main Station (record sheet of cultural monument), 1973. (Available at https://iispp.npu.cz/mis_public/documentDetail.htm?id=1089564)

8) Jiří Štursa, Contemporary Architecture of Station Buildings, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXII, 1973, no. 10, pp. 502.

9) Rostislav Švácha, Jan Šrámek – Alena Šrámková, Art XXXIII, 1985, no. 1, pp. 1–26, here p. 18.

10) Hájek, note 1, p. 158.

11) Jan Urban, The Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Ground Construction XXV, 1977, no. 5, pp. 212–213.

12) Lubor Janda, Jaroslav Procházka, Ivo Válek, and Vladimír Míka, Structural Solutions of the Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Engineering Structures XXIV, 1976, no. 7, pp. 343–348.

13) Marie Benešová, The Historical Building of the Main Station in Prague in New Relationships, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIX, 1980, no. 4, pp. 177–178.

14) Josef Danda – Alena Šrámková, The Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIX, 1980, no. 4, pp. 146–149.

15) Rostislav Švácha, Jan Šrámek – Jan Bočan, Home XXVI, 1986, no. 5, pp. 3.

16) Rostislav Švácha, On Jan Šrámek, Visual Culture VIII, 1984, 8, no. 4, pp. 38–42.

17) Danda – Šrámková, note 14, p. 149.

18) Ibidem.

19) ~, The New Terminal Hall Is Already in Use, Railroad Worker XXVI, 1977, no. 17, pp. 260–261.

20) Švácha, note 9, p. 20.

Literature:

Jiří Novotný, One Hundred Years of the Prague North-South Corridor, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXI, 1962, no. 5, pp. 292.

Josef Fleissig, The Sword of the Third Five-Year Plan Cuts the Knot of Prague Transport, Defense of the People XIX, no. 245, (October 8, 1960), p. 2.

Jaromír Seidl, A Station for 210,000 Passengers, Railroad Worker I (XVII), 1967, no. 26, p. [1].

Milan Procházka, On the Competition for the Central Station in Prague, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXVI, 1967, no. 1, pp. 10–17.

Lubor Janda et al. Cassette Non-Headed Reinforced Concrete Ceiling Slab of the Main Station Hall in Prague, Acta Polytechnica Series 1 Civil Engineering, 1973, no. 5, pp. 79–84.

Ladislav Nováček, Steel Heads of Columns in the Ceiling of the Terminal Hall of Prague Main Station, Acta Polytechnica Series 1 Civil Engineering, 1973, no. 5, pp. 85–89.

Lubor Janda – Jaroslav Procházka – Ivo Válek – Vladimír Míka, Structural Solutions of the Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Engineering Structures XXIV, 1976, no. 7, pp. 343–348.

Jiří Štursa, Contemporary Architecture of Station Buildings, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXII, 1973, no. 10, pp. 502–509.

Jan Urban, The Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Ground Construction XXV, 1977, no. 5, pp. 212–213.

~, The New Terminal Hall Is Already in Use, Railroad Worker XXVI, 1977, no. 17, pp. 260–261.

jd [Josef Danda], The Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Czechoslovak Architect XXIV, 1978, no. 2, pp. 1 and 3.

Josef Danda – Jiří Štursa, Uniform Completed Style, Project XX, 1978, no. 2, pp. 35–37.

Jan Michl, Implementations and Projects in Contemporary Architecture, Prague 1978, pp. 70–71.

Josef Danda – Alena Šrámková, The Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIX, 1980, no. 4, pp. 146–149.

Jiří Hrůza, The Main Station in Prague, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIX, 1980, no. 4, pp. 150–151.

Marie Benešová, The Historical Building of the Main Station in Prague in New Relationships, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIX, 1980, no. 4, pp. 177–178.

Jiří Ševčík, Modernism, Postmodernism, Mannerism, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XL, 1981, pp. 135–139.

Rostislav Švácha, On Jan Šrámek, Visual Culture VIII, 1984, 8, no. 4, pp. 38–42.

Rostislav Švácha, Jan Šrámek – Alena Šrámková, Art XXXIII, 1985, no. 1, pp. 1–26.

Rostislav Švácha, Jan Šrámek – Jan Bočan, Home XXVI, 1986, no. 5, pp. 3.

Josef Danda, Our Railway Stations. Prague 1988.

Věra Konečná, Interview with Alena Šrámková, Architect LVII, 2006, no. 1–2, pp. 79.

Věra Konečná, Interview with Jan Bočan, Architect LVII, 2006, no. 1–2, pp. 80.

Karel Hájek, Architect Josef Danda, Prague 2007, pp. 143–171;

Oldřich Ševčík – Ondřej Beneš, Architecture of the 1960s. "Golden Sixties" in Czech Architecture of the 20th Century, Prague 2009, pp. 424–431;

Klára Pučerová, Jan Bočan, Zdeněk Rothbauer, in: Vladimír 518 (ed.), Architecture 58–89, Vol. 2, Prague 2022, pp. 375–380, here pp. 378–379.

Radomíra Sedláková, Jan Šrámek, in: Vladimír 518 (ed.), Architecture 58–89, Vol. 2, Prague 2022, pp. 88–89

Klára Brůhová, The New Terminal Hall of the Main Station, in: Petr Vorlík – Klára Brůhová (eds.), Concrete, Břasy, Boletice. Prague on the Wave of Brutalism, Prague 2019, pp. 212–215.

Kateřina Houšková, The New Terminal Building of the Main Station, in: Matyáš Kracík (ed.) – Anna Schránilová – Kateřina Houšková – Hedvika Křížová, Post-War Architecture as a Monument, Prague 2023, pp. 86–89.

Danda conceived the station in three operational parts. The entrance hall (5,600 m²) was intended for pedestrian visitors and metro passengers (80%), utilizing shops and services along its sides. Since it could not load the metro tubes and at the same time bear the forecourt parking lot, it is composed of a steel bridge structure: 33 welded I-beams, which are only 60 cm high at a span of 45.5 meters and form a single dilatational unit measuring 145 × 45.5 meters, resting on pot neoprene bearings and weighing 2,063 tons.(11) The generous free space of the hall smoothly connected to the ground floor of the three-story terminal building (4,500 m²), and was organized by a transverse row of ticket counters, behind which was situated the area for receiving and storing luggage. The floor was designed for passengers who arrived at the station by their own vehicles, taxis, or buses (20%), for which the aforementioned parking on the roof of the entrance hall served, and along with other ticketing and services, it primarily formed a waiting room on the open gallery. The terminal building consists of a reinforced concrete skeleton in a nine-meter module; the steel columns of the last floor support its ceiling, bearing the roadway of the corridor. This too is designed as a smoothly supported unit without expansion joints – a reinforced concrete cassette slab with ribs every meter is 65 cm high at dimensions of 145 × 46.5 m.(12) Finally, the third operational part, including a restaurant, shops, and long-term waiting areas, was to consist of the original Fantova building, operationally connected and reconstructed according to a special project by Danda in cooperation with Zdeněk Vávra and František Flašar from the State Institute for the Reconstruction of Monumental Towns and Objects, which was later taken over by Jarmila Růzhová-Janáčková, but which had not been completed until recently. Just the fact that the roadway of the corridor ultimately ended up more than half a meter above the base of its façade contributed to the fact that the building then became a “monstrous fragment”.(13)

Architecturally managing such a primarily transport-related, extraordinarily extensive, and additionally underground construction was not an easy task. The team of Jan Šrámek, Alena Šrámková, and Jan Bočan, whose project was temporarily replaced by Zdeněk Rothbauer, managed to cultivate its straightforward, modernist spatial concept with inventive detail – creating an interior on a scale with the exterior.(14) At the level of the floor plan, they utilized a rigorous grouping of functional units into blocks with rounded corners, which, applied equally carefully in sections, create fabion transitions between the floor and the wall, and in more complex places of joints, distinctive sculptural formations. Rostislav Švácha considers this approach, from graphic to spatial, characteristic of the collaboration between Jan Šrámek on one side, and Jan Bočan with Zdeněk Rothbauer on the other, in works on exactly the opposite end of the typological spectrum, namely the representative interiors of diplomatic offices, whether designed by Karel Filsak, or by the authors themselves, as was the case with the embassy in London, for which they received the Royal Institute of British Architects Award in 1970.(16) Among the characteristic features of that historical period is that Šrámek’s “even over-cultivated harmonies of color and shape”(16) resonated in the station hall, which, completely in line with its transportation purpose, also utilized a glaring signal red. With it, the architects drew into their game its extraordinary constructions and technical installations: the cassette shape of the concrete ceiling slab is projected onto its cladding, the steel beam became the main motive of the only façade, while the beams fade into the shadows behind the luminaires, suspended at the level of their bottom flange, from which emerge again the red ducts of the air conditioning. Such “emphasis on the technical properties of construction components”(17) is closely related to the contemporaneously designed and completed Parisian icon of the technocratic style, later dubbed “high-tech.” Somewhere on the border of the artistic and industrial stands the streamlined patterns of the paving, which, according to her own words, “expanded upon” by Alena Šrámková, as well as the stainless steel frames of cashier booths and doors. The glazed stair towers in front of the façade and on the roof of the hall were originally to be casings for the colorfully glowing glass sculptures of Stanislav Libenský.

The realization of the work, “essentially identical with the intentions of the project”,(18) progressed rapidly for its time. Construction began in 1972 with the piloting of the foundations; the steel constructions of the entrance hall were manufactured and assembled by the Vítkovice Ironworks in 1973, the cassette ceiling of the terminal building was completed by Metrostav in 1974, and in September 1976, the first passengers began passing through the southern part of the entrance hall. After the ceremonial opening of the entire station on July 1, 1977(19), a least the glazing of the towers and the completion of the ramp leading to the forecourt followed in 1978, and in the following year, the park modifications, on which the Šrámek couple collaborated with Otakar Kuča in their first proposal in 1977.(20)

Lukáš Beran

Notes:

1) Karel Hájek, Architect Josef Danda, Prague 2007, pp. 143–171.

2) Jiří Novotný, One Hundred Years of the Prague North-South Corridor, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXI, 1962, no. 5, pp. 292.

3) Milan Procházka, On the Competition for the Central Station in Prague, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXVI, 1967, no. 1, pp. 10–17.

4) Jaromír Seidl, A Station for 210,000 Passengers, Railroad Worker I (XVII), 1967, no. 26, p. [1].

5) In 1963, Emanuel Poche rehabilitated it in his popular guide, who also prepared the architectural part of the successful exhibition at Hluboká Castle in 1966. Emanuel Poche, Prague Step by Step: A Guide to the City, Prague 1963; Jiří Kotalík (ed.), Czech Art Nouveau: Art 1900. Exhibition Catalog: Alšova South Bohemian Gallery – National Gallery in Prague – Academy of Fine Arts 1966.

6) Oldřich Dostál – Věra Konečná, Prague Art Nouveau, in: Zdislav Buříval (ed.), Centennial Prague II, 1966, pp. 80–101, here p. 91.

7) Compare: Miloš Pistorius, Main Station (record sheet of cultural monument), 1973. (Available at https://iispp.npu.cz/mis_public/documentDetail.htm?id=1089564)

8) Jiří Štursa, Contemporary Architecture of Station Buildings, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXII, 1973, no. 10, pp. 502.

9) Rostislav Švácha, Jan Šrámek – Alena Šrámková, Art XXXIII, 1985, no. 1, pp. 1–26, here p. 18.

10) Hájek, note 1, p. 158.

11) Jan Urban, The Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Ground Construction XXV, 1977, no. 5, pp. 212–213.

12) Lubor Janda, Jaroslav Procházka, Ivo Válek, and Vladimír Míka, Structural Solutions of the Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Engineering Structures XXIV, 1976, no. 7, pp. 343–348.

13) Marie Benešová, The Historical Building of the Main Station in Prague in New Relationships, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIX, 1980, no. 4, pp. 177–178.

14) Josef Danda – Alena Šrámková, The Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIX, 1980, no. 4, pp. 146–149.

15) Rostislav Švácha, Jan Šrámek – Jan Bočan, Home XXVI, 1986, no. 5, pp. 3.

16) Rostislav Švácha, On Jan Šrámek, Visual Culture VIII, 1984, 8, no. 4, pp. 38–42.

17) Danda – Šrámková, note 14, p. 149.

18) Ibidem.

19) ~, The New Terminal Hall Is Already in Use, Railroad Worker XXVI, 1977, no. 17, pp. 260–261.

20) Švácha, note 9, p. 20.

Literature:

Jiří Novotný, One Hundred Years of the Prague North-South Corridor, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXI, 1962, no. 5, pp. 292.

Josef Fleissig, The Sword of the Third Five-Year Plan Cuts the Knot of Prague Transport, Defense of the People XIX, no. 245, (October 8, 1960), p. 2.

Jaromír Seidl, A Station for 210,000 Passengers, Railroad Worker I (XVII), 1967, no. 26, p. [1].

Milan Procházka, On the Competition for the Central Station in Prague, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXVI, 1967, no. 1, pp. 10–17.

Lubor Janda et al. Cassette Non-Headed Reinforced Concrete Ceiling Slab of the Main Station Hall in Prague, Acta Polytechnica Series 1 Civil Engineering, 1973, no. 5, pp. 79–84.

Ladislav Nováček, Steel Heads of Columns in the Ceiling of the Terminal Hall of Prague Main Station, Acta Polytechnica Series 1 Civil Engineering, 1973, no. 5, pp. 85–89.

Lubor Janda – Jaroslav Procházka – Ivo Válek – Vladimír Míka, Structural Solutions of the Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Engineering Structures XXIV, 1976, no. 7, pp. 343–348.

Jiří Štursa, Contemporary Architecture of Station Buildings, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXII, 1973, no. 10, pp. 502–509.

Jan Urban, The Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Ground Construction XXV, 1977, no. 5, pp. 212–213.

~, The New Terminal Hall Is Already in Use, Railroad Worker XXVI, 1977, no. 17, pp. 260–261.

jd [Josef Danda], The Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Czechoslovak Architect XXIV, 1978, no. 2, pp. 1 and 3.

Josef Danda – Jiří Štursa, Uniform Completed Style, Project XX, 1978, no. 2, pp. 35–37.

Jan Michl, Implementations and Projects in Contemporary Architecture, Prague 1978, pp. 70–71.

Josef Danda – Alena Šrámková, The Terminal Hall of the Main Station in Prague, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIX, 1980, no. 4, pp. 146–149.

Jiří Hrůza, The Main Station in Prague, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIX, 1980, no. 4, pp. 150–151.

Marie Benešová, The Historical Building of the Main Station in Prague in New Relationships, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XXXIX, 1980, no. 4, pp. 177–178.

Jiří Ševčík, Modernism, Postmodernism, Mannerism, Architecture of Czechoslovakia XL, 1981, pp. 135–139.

Rostislav Švácha, On Jan Šrámek, Visual Culture VIII, 1984, 8, no. 4, pp. 38–42.

Rostislav Švácha, Jan Šrámek – Alena Šrámková, Art XXXIII, 1985, no. 1, pp. 1–26.

Rostislav Švácha, Jan Šrámek – Jan Bočan, Home XXVI, 1986, no. 5, pp. 3.

Josef Danda, Our Railway Stations. Prague 1988.

Věra Konečná, Interview with Alena Šrámková, Architect LVII, 2006, no. 1–2, pp. 79.

Věra Konečná, Interview with Jan Bočan, Architect LVII, 2006, no. 1–2, pp. 80.

Karel Hájek, Architect Josef Danda, Prague 2007, pp. 143–171;

Oldřich Ševčík – Ondřej Beneš, Architecture of the 1960s. "Golden Sixties" in Czech Architecture of the 20th Century, Prague 2009, pp. 424–431;

Klára Pučerová, Jan Bočan, Zdeněk Rothbauer, in: Vladimír 518 (ed.), Architecture 58–89, Vol. 2, Prague 2022, pp. 375–380, here pp. 378–379.

Radomíra Sedláková, Jan Šrámek, in: Vladimír 518 (ed.), Architecture 58–89, Vol. 2, Prague 2022, pp. 88–89

Klára Brůhová, The New Terminal Hall of the Main Station, in: Petr Vorlík – Klára Brůhová (eds.), Concrete, Břasy, Boletice. Prague on the Wave of Brutalism, Prague 2019, pp. 212–215.

Kateřina Houšková, The New Terminal Building of the Main Station, in: Matyáš Kracík (ed.) – Anna Schránilová – Kateřina Houšková – Hedvika Křížová, Post-War Architecture as a Monument, Prague 2023, pp. 86–89.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

4 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Jako rodilý Pražan

Tereza

07.12.23 08:34

Teda,...

šakal

08.12.23 10:51

Co delat ? (Ptal se Lenin)

Dr. Luscuniol

11.12.23 09:23

Jo!...

šakal

12.12.23 11:28

show all comments