Villa at Barbořina

Svatopluk Sládeček and his Zlín studio New Work have it doubly hard. They walk against the tide not once, but twice. The focus of the studio's work lies in Zlín and its surroundings, in an area that has long since become alienated from its great tradition of progressive Baťa architecture, where there are few accommodating clients and building officials, and for many years has been lacking an atmosphere conducive to architectural quality. In this respect, Sládeček's New Work aligns with Kiszko's Havířov Arkis, the Cheb Atelier 69, the Náchod team of Rak-Rydl-Skalický, Ústí's Jan Jehlík, and several other similar enthusiastic loners who fight for good architecture far from the strong centers of contemporary Czech architectural creation. The burden of Sládeček's fate also lies in the decision that his projects and buildings will not look exactly like the typical products of our great architectural centers; that they simply will not conform to some "central" customs, be it in ideological concepts, style, or forms.

In almost all of Sládeček's houses, of which there are now quite a few, we would find peculiarities that are simply not in vogue right now in Prague or Brno. The architect and his New Work thus expose themselves to a double danger. The local clientele may see Sládeček and his team as mere eccentrics, modernists at any cost, who do not want to learn to design the right and humanly understandable architecture. Architects and critics from major centers may view the deviations of New Work from the "current" or "central" norm as a manifestation of peripherality and provinciality. However, so far, Sládeček's studio has fortunately not been swayed by these risks and bravely, and mostly successfully, weaves through them from one of its buildings to the next.

For the moment, I will set aside the fact that rather than boxiness, Sládeček's work is characterized by a joy in shaping. The Zlín architect has committed far worse things. When we in Prague finally agreed that contemporary Czech architecture should cut itself off from postmodernism because we found this trend to be outdated and populist, Sládeček built a family house in Štípa near Zlín that ostentatiously claims an affiliation with the legacy of postmodernism's founder, Robert Venturi. And when neofunctionalism fell out of favor in Prague, as it too began to seem like one of the postmodern varieties, Sládeček started drawing a villa for Kroměříž that again refuses to conform to Prague's manners, because it is ostentatiously and exuberantly neofunctionalist.

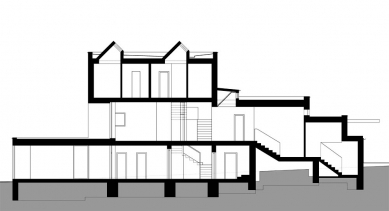

The architectural concept of this Kroměříž villa, however, does not lie solely in the fact that the architect made it white with flat roofs; nor in the way he incorporated windows into its façades just as functionalist Josef Kranz did at the Brno café ERA; nor in the way he shaped the main living area of the villa like a captain's bridge, touching upon the nautical background of the functionalist style; nor in the nice aerodynamic rounding of the corners of this main living area, following the example of Krejcar's Machnáč, the Paris pavilion from 1937, or Frič's villa by Ladislav Žák, if we limit our examples of late functionalism's penchant for rounding to Czech creators. All these features form merely an external shell for the organization of the interior, which should represent the basis of architectural solutions for all family houses. I believe that Sládeček's Kroměříž house also found its foundation in the understanding of the interior—and everything that connects to it—and I also believe that the distinctive neofunctionalist body of the Kroměříž villa was born as a consequence of fundamental decisions about the shape of the internal space and that it is connected to this space as one unit.

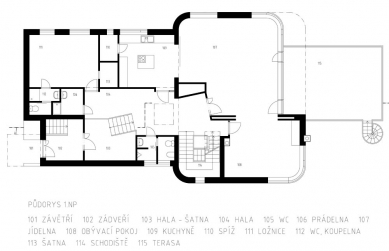

The house stands on an elevation providing a beautiful view of the panorama of historic Kroměříž with its castle, the Church of St. Moritz, and the two famous gardens. Therefore, the architect agreed with his clients to open the space of the villa to this view as much as possible—and this was best achieved by functionalist buildings in the twentieth century; that's probably where this model originated. The viewpoint is directed towards two sides of the main living space, logically connected by a Krejcar-style curved glass quarter-arc. However, the openness of the interior could conflict with the demands for privacy, meaning that it should prevent nosy neighbors and passersby from peeking inside. This problem the architect solved in agreement with the builders by raising the main living areas of the house and its terrace to a height where hardly anyone can see in, setting them on an elongated, narrower base.

The main living spaces connect to each other in several ways. Their composition expands in warm months with the terrace, partially covered by a protrusion from the second living floor above. The architect equipped these spaces with lighting and furniture, partly purchased and partly designed according to his own plans, as sometimes indicated by the elegant rounding similar to the shape of the upper floors of the villa. Lovers of architecture from the 1920s and 1930s, of which Sládeček's clients also know a thing or two, will appreciate the subtle references to the interior of Müller’s villa by Adolf Loos and to the interiors of the Tugendhat villa. However, the architect's spatial play begins already at the entrance to the house, in the entrance hall, from where the visitor ascends a short staircase to the main living level, and then suddenly their path curves slightly to the left, to a point where, after a few more steps, the most impressive view of the Kroměříž panorama opens up to them—towards the rounded, glazed corner of the large living hall.

The hood that conceals this strong spatial sequence features an equally strong, really unmistakable shape that can evoke various subconscious associations in us. When looking at it, we might think of a steamboat with a high captain's bridge or perhaps the Sphinx, which should rightly be looking straight ahead, but instead is glancing slightly down at the old city towers. Further debate about Sládeček's villa will probably revolve around the architect's choice of neofunctionalist style. However, one should not forget the essence of the architect's concept, which we should seek more in the interior than in the exterior of the Kroměříž house. And that the architect played masterfully with this interior, I believe, is a sentiment shared not only by me, but also by Sládeček's clients, who are highly satisfied with his work—just as it should always be with family houses. For when an architect walks against the tide, it doesn't necessarily mean they will never find clients tuned to the same wavelength.

In almost all of Sládeček's houses, of which there are now quite a few, we would find peculiarities that are simply not in vogue right now in Prague or Brno. The architect and his New Work thus expose themselves to a double danger. The local clientele may see Sládeček and his team as mere eccentrics, modernists at any cost, who do not want to learn to design the right and humanly understandable architecture. Architects and critics from major centers may view the deviations of New Work from the "current" or "central" norm as a manifestation of peripherality and provinciality. However, so far, Sládeček's studio has fortunately not been swayed by these risks and bravely, and mostly successfully, weaves through them from one of its buildings to the next.

For the moment, I will set aside the fact that rather than boxiness, Sládeček's work is characterized by a joy in shaping. The Zlín architect has committed far worse things. When we in Prague finally agreed that contemporary Czech architecture should cut itself off from postmodernism because we found this trend to be outdated and populist, Sládeček built a family house in Štípa near Zlín that ostentatiously claims an affiliation with the legacy of postmodernism's founder, Robert Venturi. And when neofunctionalism fell out of favor in Prague, as it too began to seem like one of the postmodern varieties, Sládeček started drawing a villa for Kroměříž that again refuses to conform to Prague's manners, because it is ostentatiously and exuberantly neofunctionalist.

The architectural concept of this Kroměříž villa, however, does not lie solely in the fact that the architect made it white with flat roofs; nor in the way he incorporated windows into its façades just as functionalist Josef Kranz did at the Brno café ERA; nor in the way he shaped the main living area of the villa like a captain's bridge, touching upon the nautical background of the functionalist style; nor in the nice aerodynamic rounding of the corners of this main living area, following the example of Krejcar's Machnáč, the Paris pavilion from 1937, or Frič's villa by Ladislav Žák, if we limit our examples of late functionalism's penchant for rounding to Czech creators. All these features form merely an external shell for the organization of the interior, which should represent the basis of architectural solutions for all family houses. I believe that Sládeček's Kroměříž house also found its foundation in the understanding of the interior—and everything that connects to it—and I also believe that the distinctive neofunctionalist body of the Kroměříž villa was born as a consequence of fundamental decisions about the shape of the internal space and that it is connected to this space as one unit.

The house stands on an elevation providing a beautiful view of the panorama of historic Kroměříž with its castle, the Church of St. Moritz, and the two famous gardens. Therefore, the architect agreed with his clients to open the space of the villa to this view as much as possible—and this was best achieved by functionalist buildings in the twentieth century; that's probably where this model originated. The viewpoint is directed towards two sides of the main living space, logically connected by a Krejcar-style curved glass quarter-arc. However, the openness of the interior could conflict with the demands for privacy, meaning that it should prevent nosy neighbors and passersby from peeking inside. This problem the architect solved in agreement with the builders by raising the main living areas of the house and its terrace to a height where hardly anyone can see in, setting them on an elongated, narrower base.

The main living spaces connect to each other in several ways. Their composition expands in warm months with the terrace, partially covered by a protrusion from the second living floor above. The architect equipped these spaces with lighting and furniture, partly purchased and partly designed according to his own plans, as sometimes indicated by the elegant rounding similar to the shape of the upper floors of the villa. Lovers of architecture from the 1920s and 1930s, of which Sládeček's clients also know a thing or two, will appreciate the subtle references to the interior of Müller’s villa by Adolf Loos and to the interiors of the Tugendhat villa. However, the architect's spatial play begins already at the entrance to the house, in the entrance hall, from where the visitor ascends a short staircase to the main living level, and then suddenly their path curves slightly to the left, to a point where, after a few more steps, the most impressive view of the Kroměříž panorama opens up to them—towards the rounded, glazed corner of the large living hall.

The hood that conceals this strong spatial sequence features an equally strong, really unmistakable shape that can evoke various subconscious associations in us. When looking at it, we might think of a steamboat with a high captain's bridge or perhaps the Sphinx, which should rightly be looking straight ahead, but instead is glancing slightly down at the old city towers. Further debate about Sládeček's villa will probably revolve around the architect's choice of neofunctionalist style. However, one should not forget the essence of the architect's concept, which we should seek more in the interior than in the exterior of the Kroměříž house. And that the architect played masterfully with this interior, I believe, is a sentiment shared not only by me, but also by Sládeček's clients, who are highly satisfied with his work—just as it should always be with family houses. For when an architect walks against the tide, it doesn't necessarily mean they will never find clients tuned to the same wavelength.

Rostislav Švácha (written for ERA 21 6/2002)

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

4 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Cena realizace?

alquist

29.12.06 09:14

figurky

stepet

17.06.07 01:50

Rozhovory

Jan Kratochvíl

17.06.07 01:05

cena?

Martina Šišková

16.01.10 10:13

show all comments