Refuge

Pavilion of the Holy See 2018

This year's exhibition was enriched by the first exhibition of the Vatican in the otherwise inaccessible gardens of San Giorgio Maggiore Island. Eleven leading studios from around the world were invited to participate, contributing ten chapels to this remarkable installation. Among them was the Portuguese architect and Pritzker Prize winner, Eduardo Souto de Moura, whose work at this year's biennale won the Golden Lion award.

The curator of the exhibition, Professor Francesco Dal Co, advised the architects to take inspiration from the Woodland Stockholm Chapel, which was located in a cemetery. Architect Erik Gunnar Asplund designed the chapel in 1920 with the intention of highlighting its humble expression – to evoke the impression of a cottage in the woods rather than that of a divine temple. A small exhibition is also dedicated to it within the Vatican chapels.

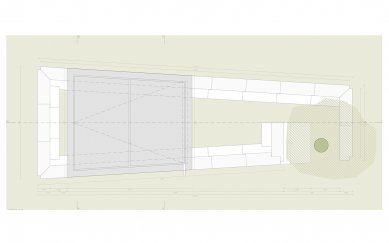

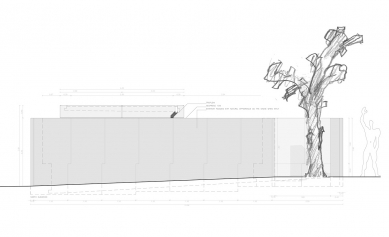

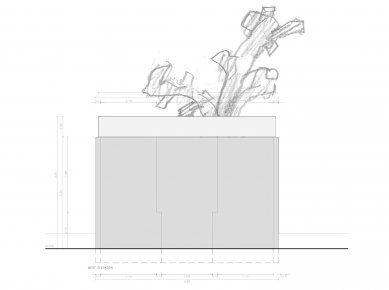

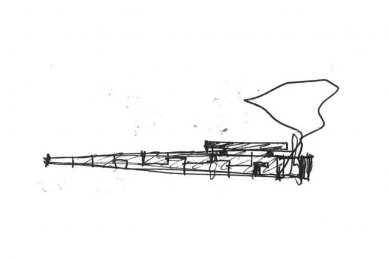

Even though the invited architects are among the internationally recognized creators, creating a place or space that has a sacred or metaphysical atmosphere is not easy at all. Eduardo Souto de Moura seized the opportunity fully, as is his custom. This is also reflected in visitors' comments: some said the chapel looks like a grave, while others assert it resembles a sanctuary from another era. The architect sowed confusion in his description: "It is not a chapel, it is not a sanctuary, and by no means a tomb; it is simply a place enclosed by four stone walls, while another stone in the center could be the altar. The entrance is shaded by a tree that we want to leave. The walls inside have a bench, on which we can sit and wait... waiting with our feet on the ground, our heads in our hands. Things themselves know when they should happen.” (David Mourão-Ferreira) For the chapel, he chose a single material: limestone from Verona. Massive blocks create walls, built in a way reminiscent of the key mechanism used by the Incas in Machu Picchu – ashlar masonry, based on stacking worked stones on top of each other without the use of mortar. The Incas were so skilled in this technique that in some walls, it is impossible to insert the tip of a knife between two stacked blocks. The mass of stone, the simplicity of joints, and the light. A kind of symbol of returning to the roots of architecture in the supposed representation of the Vatican – it also stands resiliently, unwavering in today's world, drawing strength from ancient times. The outer surface of the stone blocks is rough, almost raw – visible tool marks from the shaping process are proudly acknowledged. One could interpret the cracks and signs of time on the material as a metaphor for the storms that Venice has faced over the centuries. Inside, the walls are polished and smoothed, also hinting at a kind of comfort that the clergy has afforded itself in this world.

The curator of the exhibition, Professor Francesco Dal Co, advised the architects to take inspiration from the Woodland Stockholm Chapel, which was located in a cemetery. Architect Erik Gunnar Asplund designed the chapel in 1920 with the intention of highlighting its humble expression – to evoke the impression of a cottage in the woods rather than that of a divine temple. A small exhibition is also dedicated to it within the Vatican chapels.

Even though the invited architects are among the internationally recognized creators, creating a place or space that has a sacred or metaphysical atmosphere is not easy at all. Eduardo Souto de Moura seized the opportunity fully, as is his custom. This is also reflected in visitors' comments: some said the chapel looks like a grave, while others assert it resembles a sanctuary from another era. The architect sowed confusion in his description: "It is not a chapel, it is not a sanctuary, and by no means a tomb; it is simply a place enclosed by four stone walls, while another stone in the center could be the altar. The entrance is shaded by a tree that we want to leave. The walls inside have a bench, on which we can sit and wait... waiting with our feet on the ground, our heads in our hands. Things themselves know when they should happen.” (David Mourão-Ferreira) For the chapel, he chose a single material: limestone from Verona. Massive blocks create walls, built in a way reminiscent of the key mechanism used by the Incas in Machu Picchu – ashlar masonry, based on stacking worked stones on top of each other without the use of mortar. The Incas were so skilled in this technique that in some walls, it is impossible to insert the tip of a knife between two stacked blocks. The mass of stone, the simplicity of joints, and the light. A kind of symbol of returning to the roots of architecture in the supposed representation of the Vatican – it also stands resiliently, unwavering in today's world, drawing strength from ancient times. The outer surface of the stone blocks is rough, almost raw – visible tool marks from the shaping process are proudly acknowledged. One could interpret the cracks and signs of time on the material as a metaphor for the storms that Venice has faced over the centuries. Inside, the walls are polished and smoothed, also hinting at a kind of comfort that the clergy has afforded itself in this world.

Eva Macejková

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment