Unité d'habitation 'Typ Berlin'

|

Initially Le Corbusier's contribution to the postwar Berlin cityscape was meant to be part of the Interbau Building Exhibition of 1957 on the borders of the Tiergarten. But when he announced his intention to build a massive 17-story "residential factory" containing 557 living units, the city authorities decided that they had better find him a suitable location of his own.

An extraordinary situation really; usually the client specifies the location and the architect is expected to come up with a design appropriate to that site. One doesn't usually expect to see the client running around trying to find a patch of ground worthy of any old building that the commissioned architect has a notion to do next. But when the architect in question is the French guy with the funny glasses and a moniker like a magician's: the "master of modern architecture" himself, then allowances are understandable.

Even in 1957 the Berlin city planning committee was astute enough to realize that the opportunity to have a Le Corb building in the portfolio was not one to be passed up on. Even if it didn't fit into the Hansaviertel along with the humble contributions of other fairly distinguished architects such as Oscar Niemeyer, Alvar Aalto, Arne Jacobsen and Walter Gropius. Besides, Berlin had a postwar housing shortfall of some 100000 dwellings to deal with. So they offered the "master" the top of a hill in Charlottenburg with majestic views across the city and right next door to Werner March's imposing national socialist architecture of the 1934 Olympic Stadium to build his new Wohnmaschine for 2000 residents.

Le Corbusier's gift to Berlin was one of his limited edition, off-the-peg unités d'habitation. Number three from a total of five in this series of giant residential buildings following those of Marseille and Nantes. The design for the unités was the result of Corbusier's long-term considerations about modern urban living. He had tried several times, without success, to implement his ideas on a macro level with new plans for entire city centers (including Berlin). He proposed knocking down all the old stuff and replacing it with huge high-rise blocks-vertical villages as it were-containing all the relevant shops and leisure facilities and surrounded by parkland. Variations of these plans later spawned the anonymous housing estates and ghettos all over the world that we now all love to hate. But shortly after 1945, the prospect of clean, new dwellings with hot-and-cold running water, central heating and labor-saving facilities represented the epitome of modern life and progress in Europe.

Unfortunately Le Corb himself had no takers for his radical city projects so he condensed the idea into individual residential "factories." The first unité d'habitation in Marseille looked very promising: It had a kindergarten, theatre and sports facilities on the roof, and one floor of the block was given over to shops and offices. There were 23 types of living units from bachelor studios to apartments for families of 10. These units were based on Le Corb's "Modulor" system. Using the Fibonacci Series and "anthropometric" proportions which related to the size of a human being, he defined the ideal height, width and length of a living space for an individual and then grouped these shoebox-shaped units into a variety of maisonette apartments with balconies to suit different family sizes. The exterior appearance of the building clearly reflects this Lego brick-style construction principle, since the units have a structural as well as functional role. To emphasize the vertical village principle, the individual floors are called "streets" rather than stories.

It took years for Corbusier to work out this Modulor system and the unité designs. Therefore he saw no reason to make any particular changes when it came to "L'Unité d'habitation Berlin." Unfortunately he hadn't reckoned with the intransigence of German building regulations.

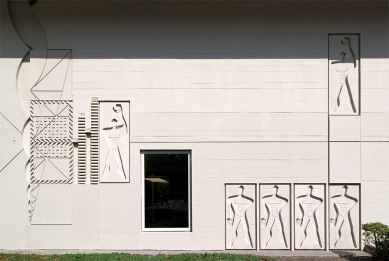

Although the building looks superficially much the same as those of Marseille and Nantes, Le Corb was forced to change the proportions of the individual units to conform to German law. This meant increasing the floor-to-floor height by almost a meter, which ended up destroying the whole balance of the building in his eyes. The seemingly abstract painted patterns on the facade in Corbusier's trademark palette of colors are the only remaining clue to the original Modulor dimensions-a defiant vestige of his original intentions.

Worse still, the integrated facilities so vital to Le Corbusier's vision of a modern social housing community such as the kindergarten on the roof and the shopping arcade on the seventh floor never even made it past the drawing board. A children's playground was later added in the grounds of the building, and a bank, post office, supermarket and launderette were squeezed into the reception area, but by then Le Corb had lost patience and washed his hands of the whole building-refusing to be further associated with it. Ironically as "Le Corbusier Haus" it, nevertheless, bears his name to this day.

That was nearly 50 years ago. It didn't take long for the Unité concept, for all its modern facilities, to be viewed as a fatally flawed idea. People just didn't use the buildings like they were expected to for some reason. Nevertheless, when the Berlin Unité was completed in 1958, there was huge demand for the new, low-rent apartments and many young families moved in. Long-term resident Ingeborg Krause talks fondly of a strong neighborhood spirit encouraged by the natural gregariousness of the children and says she has "only positive things to say" about her life in the building.

But now, 50 years later, the patter of tiny feet is a rare sound in the renovated corridors and the crumbling playground is deserted and overgrown. The building that was originally intended as low-rent accommodation was sold in 1978 to a private firm, Präzisa, who raised rents and began selling off individual apartments. Eighty per cent, they say, are now privately owned. Many of the owners-and the remaining renters-are original residents from 1958: growing old together with their home. The children have long-since grown up and moved on and a very different social structure is beginning to replace them. The new residents of Le Corbusier Haus are drawn there because of the reputation of the architect who disowned it: young architects, engineers and creative types are drawn by the prospect-and the kudos-of living in an architectural icon. They are stripping back their apartments to the basics, carefully decorating with Le Corbusier color schemes and furniture, and joining the resident's association to help ensure that the communal areas are kept as authentic as possible. The preoccupations of the older residents-that the supermarket has closed down and that they have to take a taxi to visit the doctor or the druggist, because there is no bus stop nearby-have less relevance to these youthful, mobile, salaried individuals. For them this is life in a museum-a monument-and perhaps the most that they have in common with their neighbors is the stunning view across the city.

Nevertheless-strange social mix aside-this building may be half a century old, but it seems to be still functioning. The public areas are clean, well kept and graffiti-free, and the residents are fiercely proud of their living-machine on the hill.

Sophie Lovell, Qvest-Magazin Berlin, Autumn 2003 - No. 10, p. 292-299

0 comments

add comment