Barceloneta Market

Mercado de la Barceloneta

|

| Adrià Goula |

The project meant a chance to go back to the neighborhood in an interested manner; it was no longer a trip for fun and discovery, but rather a survey of the place. The object was to identify what would enable us to reveal its qualities and to describe it accurately for the purposes of a project.

Ultimately, it was an attempt to explain a reality and to offer a new and fuller meaning to an architectural project, beyond resolving a programme or commission. As early as the competition stage we did a collage with some of César Manrique’s fantastic fish, drawings for children we hoped might embody and express the joy of these people: their liveliness, their energy, their enthusiasm in the face of frequent hardship.

The Market has always been an element of social cohesion in the neighborhood, a landmark, sometimes almost secret and visible only to its inhabitants. This condition of density that the market has in relation to the city should be a condition of the project, so that the building and its immediate surroundings actually become a clear point of reference in this corner of the city of Barcelona.

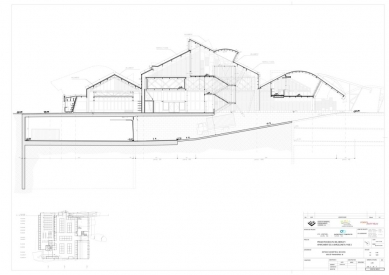

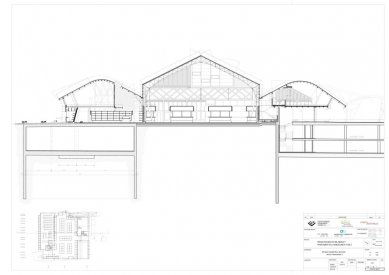

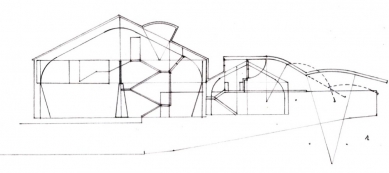

It is surprising to see now the photos we made of the market during construction, when the pieces, the bones, of this huge animal were being carried through the streets to their final place. This animal is now a prisoner in a military-imposed town plan, this neighborhood, with no chance of escape.

I think it’s nice to think of the memory of these very streets of each of these transported parts; each neighbor is witness alike to the construction, or at least some fragment of the market. It is surprising, even now, to recall that building process, which we shared with neighbors and with workers. The final construction was done in parts, little pieces of a greater reality. The assembly of these pieces is impressionable with these fragments, previously cut up in the factory to facilitate transport, and their passage through the narrow streets to the space allocated for the market.

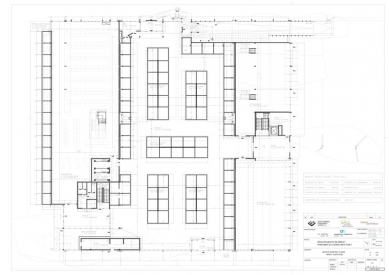

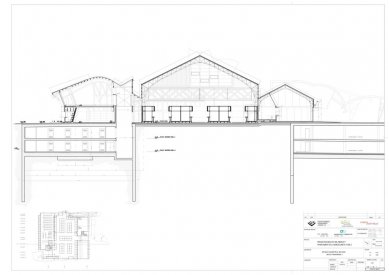

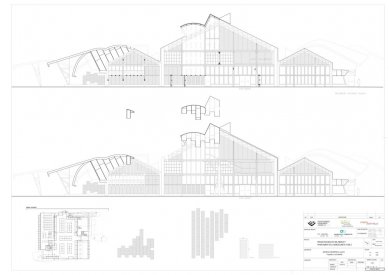

The market seeks to form part of the neighborhood, its urban fabric, and is redirected toward the squares front and rear – formerly no square existed, and the bays that made up the market crossed.

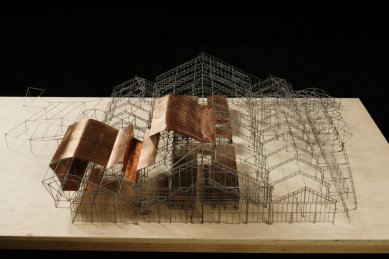

The new metal figures create new market spaces, not touching the ground, but suspended from the old structure, not a in real manner, since the two structures, the old and new, never really overlap structurally, rather they do so in a false equilibrium. The imprisoned, tamed building writhes within this space, a certain violence in its rebuilt form, acquiring a reality that lies between the memory of its former self and its new ambition. It uncurls, curls back up, and offers a succession of new spaces to discover.

0 comments

add comment