Trellick Tower

|

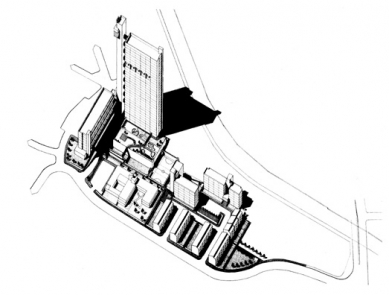

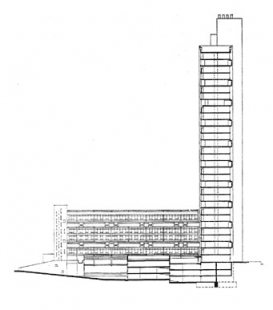

Standing at 31 stories and 322 feet tall, the Trellick Tower’s Brutalist architectural style dominates the immediate skyline. It is loosely based on Goldfinger’s earlier and smaller Balfron Tower of similar style and construction. Its completion in 1972 marked the end of an era of high-rise tower blocks, which were losing popularity due to the inherently negative social problems that plagued them. Incorporated into the design are two volumes of different but interconnected function. The main volume features the dwelling units, while a thin service tower connected at every third floor to the main tower houses the stairs, lifts, and mechanical plant.

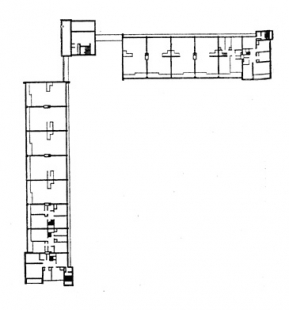

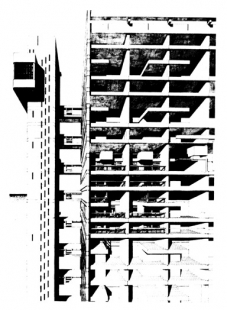

One of the most unique features besides the distinct separation of service from dwelling is the method for which the flats are accessed. Nine different types of two level flats are designed with the main entry lying on every third floor that connects to the service tower. Once inside the flat, an internal stairway directs occupants up or down into the next volume of the flat. By limiting the internal public corridors, the flat spaces above and below are able to feature spaces that stretch across the floor plate, exposing windows on both sides. This method of design offered up some of the largest flats by conventional tower block standards at the time. Known for his detailing, Goldfinger took care when designing the units. He called for dual pane glazing to help mitigate sound transmission, designed pivoting window systems for ease of cleaning, and specified individual fan coil units for each flat. Numerous space saving devices are incorporated into the design. One example is the entrance to the bathrooms where sliding doors are used in place of traditional swing doors, which would have consumed valuable floor space.

The service tower component contains the majority of the mechanical equipment in the uppermost regions. A large cantilevered plant room at the top houses an oil fired boiler along with water storage tanks. The two were grouped together in order to reduce the amount of piping and virtually eliminate the need for pumps, as water could then flow down to the flats through gravity. Interestingly, the oil powered equipment was short lived as the 1973 Oil Crisis rendered them too costly, and the flats were converted to electric heating. In staying true to his attention to detail, Goldfinger insulated the bridge elements from the main structures with neoprene gaskets in order to mitigate vibration.

Exposed concrete structure defines the aesthetics of the exterior through a simple geometric language playing with the horizontality and verticality of the various elements. The north façade features fully glazed gallery windows and continues the horizontal element of the bridges along the length of the access levels. Treatment of the south façade is articulated through the positioning of the two types of balconies, which along with the vertical supporting structure mimic the voids created by the bridging of the two vertical masses.

Although, the Trellick Tower suffered from years of neglect and a crime ridden atmosphere, it has since redeemed itself. Its designation in 1998 as a Grade II* listed building assisted in this turnaround. The local environment has seen significant reduction in crime and a change in perception with addition of CCTV and a concierge service. While a few flats are privately owned, the majority of the units are still utilized as social housing. The Trellick Tower stands as testament to the Modernist movement and its unapologetic Brutalist concrete exterior.

0 comments

add comment