The New York Times

Herbert Muschamp, the former architecture critic for The New York Times, captured the situation best when he wrote: "Since the 1970s, the prevailing law of construction in New York has been the conviction: One should not commit architecture here." Indeed, the CBS building, with its impressive ribbed facade of black granite, is probably the last truly imposing skyscraper in Manhattan, and it was completed in 1965.

The decline of the phenomenon of the New York skyscraper, caused by a gradual loss of creative energy since the 1960s and a building department system that steadily diverted fresh architectural ideas, seemed to be sealed on September 11, 2001. However, just a year before the terrorist attack, The Times commissioned Renzo Piano for a project that could signify the beginning of a skyscraper revival. The New York Times (NYT) building, which was officially opened last week, is the first truly impressive office tower constructed in Manhattan in over forty years.

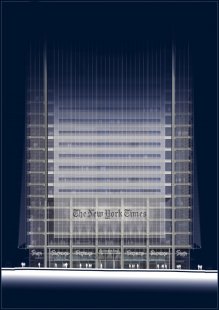

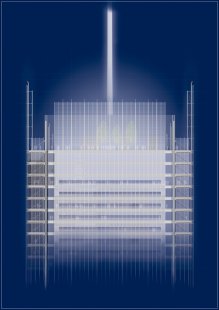

Surprisingly, this brand-new headquarters of the publishing house is barely noticeable amidst the famous bustling skyline. Tucked away on 8th Avenue, just south of Times Square and opposite the busy Port Authority Bus Terminal, the NYT could very well be the world's first hidden skyscraper. There is no doubt that it is tall—its antenna soars 319 meters above the shops, sex shops, and cafes lining the bustling sidewalks below. Neat, steel-gray, it rests on the ground as lightly as possible. With its exposed steel skeleton, the NYT does not resemble any of New York's skyscrapers. While the Woolworth, Empire State, and Chrysler buildings seem to shout: "Hey! Look at me, I'm the best in the world!", the NYT is, despite its scale and sophistication, anything but a loud example of audacity.

Piano leads one of the world's most successful architectural firms. The son of a Genoese builder made a name for himself with the Pompidou Center in Paris, completed in 1977. Since then, he has built around the world: sometimes astonishingly, but mostly in admirably restrained fashion, if at all in an inventive mode.

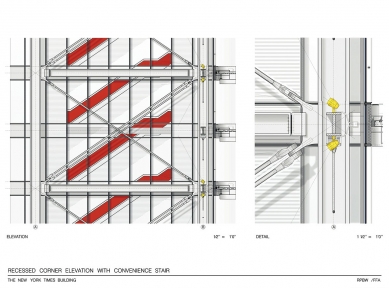

A striking difference from the typical New York office tower with its typical floors, central elevator, etc. is that Piano's 52-story building stands naked and exposed. Essentially, one could say that if the building didn't have a sunshade—colossal "Venetian blinds" made from 186,000 pearlescent white ceramic rods wrapping the building—intimate details of life inside would be on display for all to see. The windows of Manhattan's towers are usually tinted green, gray, or gold, or made from mirrored glass. All of these types of glass protect offices from sunlight and prying eyes; they also create an impression of private, introverted spaces. In such an environment, Piano's windows, which are open from floor to ceiling and outfitted with the clearest glass available, may seem even more transparent.

Nevertheless, because of all this, the NYT appears almost invisible in the Manhattan skyline. Is that a good thing? Should Piano have allowed his tower to resonate and engrave itself in memory like the Empire State or Chrysler? "Naturally, after September 11, a great debate emerged about the nature of buildings," Piano admits, sipping espresso in the bright, two-story NYT café, fourteen floors above ground, with the Empire State building seemingly perched on his shoulders in the background. "I said that it depends on openness and transparency—the necessity for the building to become, as much as possible, a normal part of the city, a public space, a vertical square. Even if you're only interested in safety, it's better to see what’s happening than to try to hide everything."

"We followed the course of The New York Times. The newspaper absorbs events from the city to feed the editorial machinery and then gives something back to the city. We wanted to create a building that somehow made New York and The Times one and the same."

The New York Times was founded in 1851 and is known as the "gray lady" thanks to its immutable, conservative, honest design and perhaps also its coolly neutral editorial style. Piano's secretive discreet tower in navy gray is an elegant reflection of the institution it serves. However, the story does not end there. Inside, the building is far from being a "gray lady." The interiors are bright, airy, and warm. The walls of the lobby, corridors, and café are covered with a layer of plaster with a swirling pattern, while others are painted almost fiery red. Because sufficient light enters the building, the electric lighting is soft, and thanks to a clever computer program, can be adjusted in an infinite number of ways throughout the day.

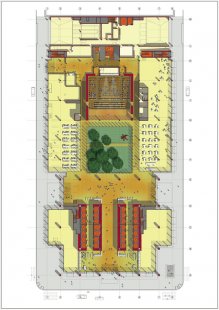

The views inside are generous: Not only can you see from the main entrance directly into the second lobby, but you can also catch a glimpse of the garden in the atrium, adorned with silver birches, and through the front glazing, even the wood-paneled interior of the 378-seat auditorium.

The New York Times occupies the first 28 floors of the slender tower along with its sister editions and management; all floors enjoy high ceiling heights; in the 24 additional floors above, real estate and legal firms reside. "The newsroom" is, however, clustered around and above the atrium garden, and appropriately remains grounded. Its three floors are nicknamed "the bakery" because editors preparing stories for the next day work here all night. The spacious interior of the newsroom is a surprise for any journalist accustomed to the chaos and clutter of a typical newspaper office. You can't help but wonder: Where has all that noise gone? After all, this is a major American newspaper. Yet there is none, not even in the late afternoon. Is it perhaps because the space evokes the impression of a cathedral? Perhaps because journalists sit alone in large cubicles set into an open plan? Or maybe not enough phones ring here? Whatever it is, one feels here like in a cross between a library and a call center equipped with the latest technology.

In one of the 24 quiet elevators, I ride to the top of the tower with Renzo Piano. "The roof is not finished," he tells me as he walks around. "We liked the idea of making a publicly accessible observation deck with a café and a rooftop garden with mature trees, as well as a pool, but for safety reasons, the plan will probably not materialize. At least not now." He lovingly points to huge cylindrical wooden water tanks, seamlessly old-fashioned New York objects. "They remind me of wine barrels," he says. "There could be a wonderful restaurant here; one could have a drink while looking at New York and beyond..." Of course, you can take the architect out of Italy, but you can't take Italy out of the architect.

Should this building even be constructed in today's ecology-oriented times? "If you really want to be green," Piano says, "you shouldn't build a high-rise in a city in the first place. But the Times wanted to be here, where it belongs. Not somewhere in a new building built on a green field in New Jersey. We can only strive for the best. The ceramic screens cool the building, which allows us to need less air conditioning; daylight penetrates most spaces, which reduces electricity consumption."

He continues his reflection: "I think that as newspapers become less tangible, they need extraordinary buildings for themselves to root in the world of everyday life, to physically connect with their readers, and to provide journalists with a place where they can settle."

In creating an extraordinary home for The New York Times, Renzo Piano quietly reinterpreted the possibilities of a Manhattan skyscraper. His project may not have the model appearance of the Empire State or Chrysler or the richness of Seagram, yet, as Piano says: "Creating a new form is very easy; creating a new form that makes sense is complex." With this mysterious, innovative, beautifully engineered building, Piano may have sparked an architectural renaissance in New York.

The decline of the phenomenon of the New York skyscraper, caused by a gradual loss of creative energy since the 1960s and a building department system that steadily diverted fresh architectural ideas, seemed to be sealed on September 11, 2001. However, just a year before the terrorist attack, The Times commissioned Renzo Piano for a project that could signify the beginning of a skyscraper revival. The New York Times (NYT) building, which was officially opened last week, is the first truly impressive office tower constructed in Manhattan in over forty years.

Surprisingly, this brand-new headquarters of the publishing house is barely noticeable amidst the famous bustling skyline. Tucked away on 8th Avenue, just south of Times Square and opposite the busy Port Authority Bus Terminal, the NYT could very well be the world's first hidden skyscraper. There is no doubt that it is tall—its antenna soars 319 meters above the shops, sex shops, and cafes lining the bustling sidewalks below. Neat, steel-gray, it rests on the ground as lightly as possible. With its exposed steel skeleton, the NYT does not resemble any of New York's skyscrapers. While the Woolworth, Empire State, and Chrysler buildings seem to shout: "Hey! Look at me, I'm the best in the world!", the NYT is, despite its scale and sophistication, anything but a loud example of audacity.

Piano leads one of the world's most successful architectural firms. The son of a Genoese builder made a name for himself with the Pompidou Center in Paris, completed in 1977. Since then, he has built around the world: sometimes astonishingly, but mostly in admirably restrained fashion, if at all in an inventive mode.

A striking difference from the typical New York office tower with its typical floors, central elevator, etc. is that Piano's 52-story building stands naked and exposed. Essentially, one could say that if the building didn't have a sunshade—colossal "Venetian blinds" made from 186,000 pearlescent white ceramic rods wrapping the building—intimate details of life inside would be on display for all to see. The windows of Manhattan's towers are usually tinted green, gray, or gold, or made from mirrored glass. All of these types of glass protect offices from sunlight and prying eyes; they also create an impression of private, introverted spaces. In such an environment, Piano's windows, which are open from floor to ceiling and outfitted with the clearest glass available, may seem even more transparent.

Nevertheless, because of all this, the NYT appears almost invisible in the Manhattan skyline. Is that a good thing? Should Piano have allowed his tower to resonate and engrave itself in memory like the Empire State or Chrysler? "Naturally, after September 11, a great debate emerged about the nature of buildings," Piano admits, sipping espresso in the bright, two-story NYT café, fourteen floors above ground, with the Empire State building seemingly perched on his shoulders in the background. "I said that it depends on openness and transparency—the necessity for the building to become, as much as possible, a normal part of the city, a public space, a vertical square. Even if you're only interested in safety, it's better to see what’s happening than to try to hide everything."

"We followed the course of The New York Times. The newspaper absorbs events from the city to feed the editorial machinery and then gives something back to the city. We wanted to create a building that somehow made New York and The Times one and the same."

The New York Times was founded in 1851 and is known as the "gray lady" thanks to its immutable, conservative, honest design and perhaps also its coolly neutral editorial style. Piano's secretive discreet tower in navy gray is an elegant reflection of the institution it serves. However, the story does not end there. Inside, the building is far from being a "gray lady." The interiors are bright, airy, and warm. The walls of the lobby, corridors, and café are covered with a layer of plaster with a swirling pattern, while others are painted almost fiery red. Because sufficient light enters the building, the electric lighting is soft, and thanks to a clever computer program, can be adjusted in an infinite number of ways throughout the day.

The views inside are generous: Not only can you see from the main entrance directly into the second lobby, but you can also catch a glimpse of the garden in the atrium, adorned with silver birches, and through the front glazing, even the wood-paneled interior of the 378-seat auditorium.

The New York Times occupies the first 28 floors of the slender tower along with its sister editions and management; all floors enjoy high ceiling heights; in the 24 additional floors above, real estate and legal firms reside. "The newsroom" is, however, clustered around and above the atrium garden, and appropriately remains grounded. Its three floors are nicknamed "the bakery" because editors preparing stories for the next day work here all night. The spacious interior of the newsroom is a surprise for any journalist accustomed to the chaos and clutter of a typical newspaper office. You can't help but wonder: Where has all that noise gone? After all, this is a major American newspaper. Yet there is none, not even in the late afternoon. Is it perhaps because the space evokes the impression of a cathedral? Perhaps because journalists sit alone in large cubicles set into an open plan? Or maybe not enough phones ring here? Whatever it is, one feels here like in a cross between a library and a call center equipped with the latest technology.

In one of the 24 quiet elevators, I ride to the top of the tower with Renzo Piano. "The roof is not finished," he tells me as he walks around. "We liked the idea of making a publicly accessible observation deck with a café and a rooftop garden with mature trees, as well as a pool, but for safety reasons, the plan will probably not materialize. At least not now." He lovingly points to huge cylindrical wooden water tanks, seamlessly old-fashioned New York objects. "They remind me of wine barrels," he says. "There could be a wonderful restaurant here; one could have a drink while looking at New York and beyond..." Of course, you can take the architect out of Italy, but you can't take Italy out of the architect.

Should this building even be constructed in today's ecology-oriented times? "If you really want to be green," Piano says, "you shouldn't build a high-rise in a city in the first place. But the Times wanted to be here, where it belongs. Not somewhere in a new building built on a green field in New Jersey. We can only strive for the best. The ceramic screens cool the building, which allows us to need less air conditioning; daylight penetrates most spaces, which reduces electricity consumption."

He continues his reflection: "I think that as newspapers become less tangible, they need extraordinary buildings for themselves to root in the world of everyday life, to physically connect with their readers, and to provide journalists with a place where they can settle."

In creating an extraordinary home for The New York Times, Renzo Piano quietly reinterpreted the possibilities of a Manhattan skyscraper. His project may not have the model appearance of the Empire State or Chrysler or the richness of Seagram, yet, as Piano says: "Creating a new form is very easy; creating a new form that makes sense is complex." With this mysterious, innovative, beautifully engineered building, Piano may have sparked an architectural renaissance in New York.

Jonathan Glancey (The Guardian, 26.11.2007)

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

nadhera

hetzer

23.05.08 12:11

show all comments