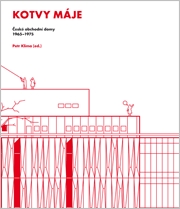

Shopping Center Ještěd

Behind the Ještěd shopping center

Many works by outstanding Czechoslovak architects, designed in the late sixties for a better future, began to serve as tools of normalization. Moreover, they were anonymous tools, as their authors were often hindered by publication bans. A decade later, the value of these buildings was denied again by a generation reflecting late on postmodernism. It's no wonder that the public still cannot appreciate them, even though they would have long accepted them as their own. This is especially true for department stores, which now face new practical requirements.

The Liberec shopping center Ještěd (better than department store, as it was planned from the beginning for multiple entities) is apparently awaiting demolition after years of poor usage. The quality of the work of architects Miroslav Masák and Karel Hubáček, structural engineer Václav Voda and their collaborators Jiří Suchomel, Mirko Baum, or Martin Rajniš from the years 1968-1979 have already been acknowledged, albeit unheard, by those more qualified /1. I would only like to point out a certain irony that accompanies the demise of this building.

In addition to high-tech architecture, the thinking on the grounds of the then SIAL, especially Kindergarten, leaned towards interdisciplinarity, spurred by an interest in sociology and psychology. Since at least 1967, the opinions of Team 10 and their critique of modernist urban dogmas, formulated in the Athens Charter, influenced by insights from these disciplines /4, were not unknown to the Czech architectural public (thanks to Milan Hon /2 and later Zdeněk Zavřel /3). Under their influence, European thinking began to be interested in "living environment," "habitat," and prefer the concept of "place" over the abstract modernist "space." It was most likely architect and theorist, a member of Team 10 and the greatest creator of playgrounds, Aldo van Eyck, who began to be interested in non-European architecture – for example, the Algerian casbahs – and introduced the term cluster into urbanism, as a way of shaping public space that allows for identification and participation.

Such a labyrinthine space is also Ještěd. It is therefore unsuitable for the placement of shelves according to the sales system of Tesco Stores, which was conceived certainly no less psychologically, but entirely disregarding the place. Moreover, Ještěd does not fill its lot to the last meter, which today appears to be entirely unforgivable. An emotional relic of ideals about human coexistence will be replaced (the only one, let us not be mistaken) by a universal building, the old good endless space. I fear it will be a two-hectare and two-billion junk-space, for which Rem Koolhaas's term proposes Jana Tichá's Czech equivalent brakový prostor /5. In the developer's paradise of Czech cities, we will still find this phrase useful.

1/ Rostislav Švácha, In Defense of Ještěd. Architect 4/2005, p. 51. For the heritage protection of Ještěd, see Pavel Halík, The Ještěd Department Store as a Historical Event. Ad Architecture 1/2005.

2/ Milan Hon, Team 10. Czechoslovak Architect XIII, 1967, no. 1-2, pp. 6-7.

3/ Zdeněk Zavřel, Bakem's World. Czechoslovak Architect XV, 1969, no. 10-11, p. 3.

4/ About Team 10 see http://www.team10online.org/

5/ Rem Koolhaas, Junk Space. In: Jana Tichá (ed.), Architecture in the Information Age, Prague 2006, pp. 95-112.

Many works by outstanding Czechoslovak architects, designed in the late sixties for a better future, began to serve as tools of normalization. Moreover, they were anonymous tools, as their authors were often hindered by publication bans. A decade later, the value of these buildings was denied again by a generation reflecting late on postmodernism. It's no wonder that the public still cannot appreciate them, even though they would have long accepted them as their own. This is especially true for department stores, which now face new practical requirements.

The Liberec shopping center Ještěd (better than department store, as it was planned from the beginning for multiple entities) is apparently awaiting demolition after years of poor usage. The quality of the work of architects Miroslav Masák and Karel Hubáček, structural engineer Václav Voda and their collaborators Jiří Suchomel, Mirko Baum, or Martin Rajniš from the years 1968-1979 have already been acknowledged, albeit unheard, by those more qualified /1. I would only like to point out a certain irony that accompanies the demise of this building.

In addition to high-tech architecture, the thinking on the grounds of the then SIAL, especially Kindergarten, leaned towards interdisciplinarity, spurred by an interest in sociology and psychology. Since at least 1967, the opinions of Team 10 and their critique of modernist urban dogmas, formulated in the Athens Charter, influenced by insights from these disciplines /4, were not unknown to the Czech architectural public (thanks to Milan Hon /2 and later Zdeněk Zavřel /3). Under their influence, European thinking began to be interested in "living environment," "habitat," and prefer the concept of "place" over the abstract modernist "space." It was most likely architect and theorist, a member of Team 10 and the greatest creator of playgrounds, Aldo van Eyck, who began to be interested in non-European architecture – for example, the Algerian casbahs – and introduced the term cluster into urbanism, as a way of shaping public space that allows for identification and participation.

Such a labyrinthine space is also Ještěd. It is therefore unsuitable for the placement of shelves according to the sales system of Tesco Stores, which was conceived certainly no less psychologically, but entirely disregarding the place. Moreover, Ještěd does not fill its lot to the last meter, which today appears to be entirely unforgivable. An emotional relic of ideals about human coexistence will be replaced (the only one, let us not be mistaken) by a universal building, the old good endless space. I fear it will be a two-hectare and two-billion junk-space, for which Rem Koolhaas's term proposes Jana Tichá's Czech equivalent brakový prostor /5. In the developer's paradise of Czech cities, we will still find this phrase useful.

Lukáš Beran, August 2006

1/ Rostislav Švácha, In Defense of Ještěd. Architect 4/2005, p. 51. For the heritage protection of Ještěd, see Pavel Halík, The Ještěd Department Store as a Historical Event. Ad Architecture 1/2005.

2/ Milan Hon, Team 10. Czechoslovak Architect XIII, 1967, no. 1-2, pp. 6-7.

3/ Zdeněk Zavřel, Bakem's World. Czechoslovak Architect XV, 1969, no. 10-11, p. 3.

4/ About Team 10 see http://www.team10online.org/

5/ Rem Koolhaas, Junk Space. In: Jana Tichá (ed.), Architecture in the Information Age, Prague 2006, pp. 95-112.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

22 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

JĚŠTĚDORAMA aneb JEŠTĚDODRAMA

de ardoise

07.08.06 03:56

prostor-místo-urbanismus-Ještěd-bedna

Kaker

10.08.06 10:23

ještě že Ještěd není ještě o deset let starší,

ing.arch.Martin Krahulík

10.08.06 02:45

nechte Ještěd tam, kde je

johansen

19.09.06 05:27

konverze

kranich

19.09.06 08:13

show all comments