New Luxor Theater

|

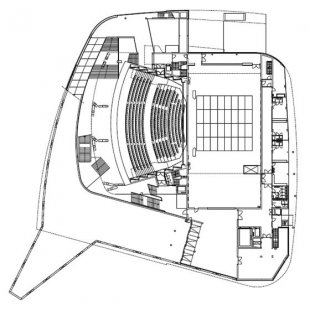

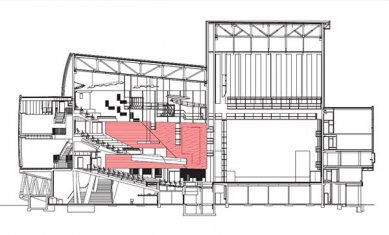

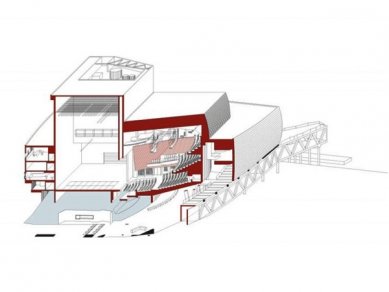

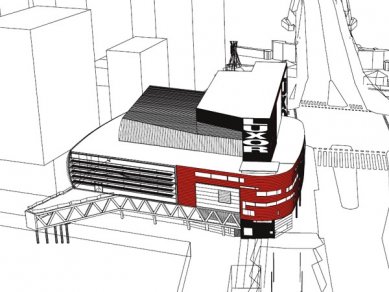

The musical theater, designed for 1520 spectators, wraps 360º around the entire building with a single facade that is meant to resemble the wooden ships docked in the harbor with its horizontal slats. The building has no main or secondary facade, no front or back, no more or less important parts. The delivery area was given the same care as the shining tower with the inscription "Luxor." The bulging western facade is as interesting as the painted eastern side. Behind the warped tomato-colored facade, its authors continued their sculptural play inside. The specifics of the assignment gave rise to both a landscape and intimate dimension of the interior. Giant ramps serve for pleasant strolling, and despite its size, the hall feels personal. However, the strongly sculptural expression does not overlook the functional aspect. One-fifth of the total budget went to the backstage facilities. Since foreign companies primarily perform at Luxor, the theater management relinquished workshops and large storage of props. It had to be perfectly resolved to supply the visiting theater groups. It is thus not a problem to get three giant trucks close to the stage at the same time. Driving down the Luxor delivery ramp is slowly becoming a dream for every truck driver. Even more attention was given to the generous entrance for theater visitors and the intermission areas (foyer Rhine and foyer Maas). A slightly dramatic concept for the interior spaces offers breathtaking views. Rotterdam's Manhattan has thus gained its very own Broadway.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment