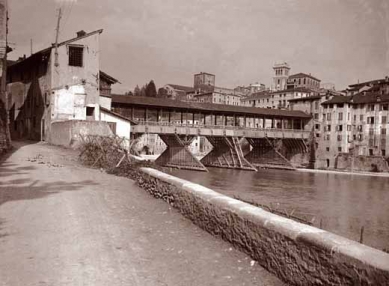

Most in Bassano

<a href="#">Ponte degli Alpini</a>

Chapter IV.

On what to take care of when building bridges, and on the place that should be chosen

Since many rivers cannot be crossed due to their width, depth, and speed, the convenience of bridges was initially considered, so it can be said that they were the main part of the road and that they were nothing more than a path created above water. They must have the same properties that we have said are required for all constructions, namely that they are comfortable, beautiful, and durable for a long time. They will be comfortable if they do not rise above the other road, and if they do rise, they should have an easy ascent, and a place should be chosen for their construction that will be the most convenient for the whole province or for the whole city, depending on whether they are made outside or inside the walls; and therefore, a place should be chosen that can be easily accessed from all sides, that is, one that will be at the center of the province or the center of the city, as Nitocris, the Babylonian queen, did at the bridge she built across the Euphrates, and not somewhere in a corner, where it might only serve the needs of a few. They will be beautiful and durable if they are made in the ways and to the dimensions that will be specifically mentioned later. But when choosing the place for their construction, it is necessary to ensure that it is chosen in such a way that it is possible to hope that the bridge built there will be eternal and where it can be constructed with the least possible cost. Therefore, a place should be chosen where the river is less deep and where the bed or bottom is flat and stable, namely rocky or tuffaceous, because (as I said in the first book when I was discussing places for laying foundations) rock and tuff are the best foundations in water; in addition, one must avoid whirlpools and pools and that part of the riverbed, which is gravelly or sandy, because sand and gravel, being continuously shifted by water floods, change the riverbed, and if it were washed out from underneath the foundations, it would necessarily lead to the collapse of the structure. But if the entire riverbed were of gravel and sand, the foundations should be made as will be stated later when I discuss stone bridges. It is also necessary to take into account that a place should be chosen where the river has a straight course, since bends and crookedness of the banks are at risk of being washed away by the water, so in such a case, the bridge would be left without support and as if on an island, and also because during floods, the water drags into these bends materials that it sweeps away from the banks and fields, and which, since they cannot directly go down, get stopped and hold back other objects and swirl around the pillars and block the openings of the arches, so that the work suffers to the point that it collapses over time due to the weight of the water. Therefore, for the construction of bridges, a place is chosen that will be in the center of the county or city, and thus convenient for all inhabitants; and where the river has a straight flow and a less deep, flat, and stable bed. But since bridges are made either of wood or stone, I will speak about both types separately and provide several drawings for them, both for old and new.

Chapter V.

On wooden bridges and the instructions that must be followed in their construction

Wooden bridges are built either for a single occasion, like those that are built in all those cases that occur in wars; of this kind, the most famous is the one that Julius Caesar built across the Rhine; or they are to serve the convenience of everyone permanently. Of this kind, we read that Hercules built the first bridge ever made across the Tiber at the place where Rome was later founded, when he killed Geryon and victoriously drove his herds across Italy, and it was called the Holy Bridge: it was laid in that part of the Tiber where King Ancus Marcius later built the Sublicius bridge, which was similarly entirely made of wood, and its beams were joined with such skill that they could be lifted and laid down as needed, and there was neither iron nor nails used; it is not known how it was made, only writers say that it was made on thick timbers, which supported others, after which it received the name Sublicius, because such timbers were called sublices in the language of the Volscians. It was the bridge that so blessed the homeland and for its glory was defended by Horatius Cocles. This bridge was near the Ripa, where several traces can be seen in the middle of the river, because it was later made of stone by praetor Aemilius Lepidus and restored by Emperor Tiberius and Antoninus Pius. Such bridges must be made to be sturdy and anchored with strong and thick beams so that there is no danger of breaking under the flow of people and animals or the weight of carts and artillery that will pass over them, and so that they cannot be destroyed by floods or water inundations. And therefore, those that are made at city gates and which we call drawbridges, because they can be raised and lowered at the discretion of those inside, are usually paved with beams and iron bands to prevent them from being broken and damaged by the wheels of carts and the feet of animals. The beams, both those that are driven into the water and those that make the width and length of the bridge, must be long and thick according to what the depth, width, and speed of the river will require. But since there are an infinite number of details, it is not possible to give a certain and fixed rule for them. I will therefore provide several drawings and state their dimensions, from which everyone can easily take their share and create a work worthy of praise according to what the opportunity provides while testing the sharpness of their intellect.

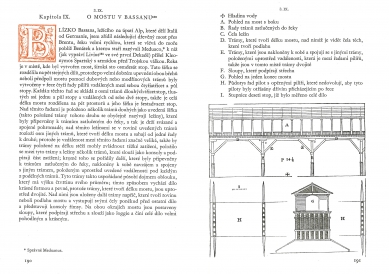

Chapter IX.

On the bridge in Bassano

Near Bassano, located at the foot of the Alps, which separate Italy from Germany, I constructed the following wooden bridge across the Brenta, a very rapid river that flows into the sea near Venice and which the ancients called Meduaco,* to which (as Livy recounts in his first Decade) Cleonymus of Sparta came with an army before the Trojan War. The river is one hundred and eighty feet wide at the place where the bridge was built. This width was divided into five equal parts, because after very good stabilization of both banks or the approaches of the bridge with oak or larch beams, four rows of piers were created in the river, spaced thirty-four and a half feet apart. Each of these rows consists of eight beams, thirty feet long, about one and a half feet thick, and spaced two feet apart, so the entire length of the bridge is divided into five spaces, and its width is twenty-six feet. Above these rows, several beams of the same length as the mentioned width are laid (these beams are commonly referred to as "lying beams"), which were anchored to the beams driven into the river, thus holding them tied and connected together; above these lying beams, eight other beams are laid in the plane of the mentioned beams, which make the length of the bridge and reach from one row to another; since the distance between these rows is quite large, so that the beams laid lengthwise could hardly bear a heavy load, several beams serving as cantilevers and supporting part of the load were laid between these beams and the lying beams; in addition, others were procured, which were anchored to the beams driven into the river, inclined towards each other and connected to another beam laid in the middle of the aforementioned distance under each of the longitudinal beams. These beams, arranged in this way, create the impression of an arch with a height of a quarter of its diameter; thus, the work emerges beautiful in form and sturdy, since the beams that make the length of the bridge are double in the middle. Above them, additional beams laid crosswise form the plane or floor of the bridge and project their faces somewhat beyond the rest of the work, representing the consoles of the cornice. At both edges of the bridge, columns are erected that support the roof and serve as loggias, making the entire structure very convenient and beautiful.

* Correctly Meduanus.

+ Water level

A. Side view of the bridge

B. Rows of beams driven into the river

C. Faces of the lying beams

D. Beams that make the length of the bridge, above which the faces of those that form the floor are visible

E. Beams that are inclined towards each other and connect with other beams laid in the middle of the distance that is between the rows of piers, so that at this point, the beams are double

F. Columns that support the roof

G. View of one end of the bridge

H. Ground plan of the rows of piles with supporting piers, which prevent these piles from being shaken by timber coming down the river

I. Scale of ten feet, by which the entire work was measured

On what to take care of when building bridges, and on the place that should be chosen

Since many rivers cannot be crossed due to their width, depth, and speed, the convenience of bridges was initially considered, so it can be said that they were the main part of the road and that they were nothing more than a path created above water. They must have the same properties that we have said are required for all constructions, namely that they are comfortable, beautiful, and durable for a long time. They will be comfortable if they do not rise above the other road, and if they do rise, they should have an easy ascent, and a place should be chosen for their construction that will be the most convenient for the whole province or for the whole city, depending on whether they are made outside or inside the walls; and therefore, a place should be chosen that can be easily accessed from all sides, that is, one that will be at the center of the province or the center of the city, as Nitocris, the Babylonian queen, did at the bridge she built across the Euphrates, and not somewhere in a corner, where it might only serve the needs of a few. They will be beautiful and durable if they are made in the ways and to the dimensions that will be specifically mentioned later. But when choosing the place for their construction, it is necessary to ensure that it is chosen in such a way that it is possible to hope that the bridge built there will be eternal and where it can be constructed with the least possible cost. Therefore, a place should be chosen where the river is less deep and where the bed or bottom is flat and stable, namely rocky or tuffaceous, because (as I said in the first book when I was discussing places for laying foundations) rock and tuff are the best foundations in water; in addition, one must avoid whirlpools and pools and that part of the riverbed, which is gravelly or sandy, because sand and gravel, being continuously shifted by water floods, change the riverbed, and if it were washed out from underneath the foundations, it would necessarily lead to the collapse of the structure. But if the entire riverbed were of gravel and sand, the foundations should be made as will be stated later when I discuss stone bridges. It is also necessary to take into account that a place should be chosen where the river has a straight course, since bends and crookedness of the banks are at risk of being washed away by the water, so in such a case, the bridge would be left without support and as if on an island, and also because during floods, the water drags into these bends materials that it sweeps away from the banks and fields, and which, since they cannot directly go down, get stopped and hold back other objects and swirl around the pillars and block the openings of the arches, so that the work suffers to the point that it collapses over time due to the weight of the water. Therefore, for the construction of bridges, a place is chosen that will be in the center of the county or city, and thus convenient for all inhabitants; and where the river has a straight flow and a less deep, flat, and stable bed. But since bridges are made either of wood or stone, I will speak about both types separately and provide several drawings for them, both for old and new.

Chapter V.

On wooden bridges and the instructions that must be followed in their construction

Wooden bridges are built either for a single occasion, like those that are built in all those cases that occur in wars; of this kind, the most famous is the one that Julius Caesar built across the Rhine; or they are to serve the convenience of everyone permanently. Of this kind, we read that Hercules built the first bridge ever made across the Tiber at the place where Rome was later founded, when he killed Geryon and victoriously drove his herds across Italy, and it was called the Holy Bridge: it was laid in that part of the Tiber where King Ancus Marcius later built the Sublicius bridge, which was similarly entirely made of wood, and its beams were joined with such skill that they could be lifted and laid down as needed, and there was neither iron nor nails used; it is not known how it was made, only writers say that it was made on thick timbers, which supported others, after which it received the name Sublicius, because such timbers were called sublices in the language of the Volscians. It was the bridge that so blessed the homeland and for its glory was defended by Horatius Cocles. This bridge was near the Ripa, where several traces can be seen in the middle of the river, because it was later made of stone by praetor Aemilius Lepidus and restored by Emperor Tiberius and Antoninus Pius. Such bridges must be made to be sturdy and anchored with strong and thick beams so that there is no danger of breaking under the flow of people and animals or the weight of carts and artillery that will pass over them, and so that they cannot be destroyed by floods or water inundations. And therefore, those that are made at city gates and which we call drawbridges, because they can be raised and lowered at the discretion of those inside, are usually paved with beams and iron bands to prevent them from being broken and damaged by the wheels of carts and the feet of animals. The beams, both those that are driven into the water and those that make the width and length of the bridge, must be long and thick according to what the depth, width, and speed of the river will require. But since there are an infinite number of details, it is not possible to give a certain and fixed rule for them. I will therefore provide several drawings and state their dimensions, from which everyone can easily take their share and create a work worthy of praise according to what the opportunity provides while testing the sharpness of their intellect.

sv. III, kap. IV, str. 179-180

Chapter IX.

On the bridge in Bassano

Near Bassano, located at the foot of the Alps, which separate Italy from Germany, I constructed the following wooden bridge across the Brenta, a very rapid river that flows into the sea near Venice and which the ancients called Meduaco,* to which (as Livy recounts in his first Decade) Cleonymus of Sparta came with an army before the Trojan War. The river is one hundred and eighty feet wide at the place where the bridge was built. This width was divided into five equal parts, because after very good stabilization of both banks or the approaches of the bridge with oak or larch beams, four rows of piers were created in the river, spaced thirty-four and a half feet apart. Each of these rows consists of eight beams, thirty feet long, about one and a half feet thick, and spaced two feet apart, so the entire length of the bridge is divided into five spaces, and its width is twenty-six feet. Above these rows, several beams of the same length as the mentioned width are laid (these beams are commonly referred to as "lying beams"), which were anchored to the beams driven into the river, thus holding them tied and connected together; above these lying beams, eight other beams are laid in the plane of the mentioned beams, which make the length of the bridge and reach from one row to another; since the distance between these rows is quite large, so that the beams laid lengthwise could hardly bear a heavy load, several beams serving as cantilevers and supporting part of the load were laid between these beams and the lying beams; in addition, others were procured, which were anchored to the beams driven into the river, inclined towards each other and connected to another beam laid in the middle of the aforementioned distance under each of the longitudinal beams. These beams, arranged in this way, create the impression of an arch with a height of a quarter of its diameter; thus, the work emerges beautiful in form and sturdy, since the beams that make the length of the bridge are double in the middle. Above them, additional beams laid crosswise form the plane or floor of the bridge and project their faces somewhat beyond the rest of the work, representing the consoles of the cornice. At both edges of the bridge, columns are erected that support the roof and serve as loggias, making the entire structure very convenient and beautiful.

* Correctly Meduanus.

sv. III, kap. IX, str. 190-191

+ Water level

A. Side view of the bridge

B. Rows of beams driven into the river

C. Faces of the lying beams

D. Beams that make the length of the bridge, above which the faces of those that form the floor are visible

E. Beams that are inclined towards each other and connect with other beams laid in the middle of the distance that is between the rows of piers, so that at this point, the beams are double

F. Columns that support the roof

G. View of one end of the bridge

H. Ground plan of the rows of piles with supporting piers, which prevent these piles from being shaken by timber coming down the river

I. Scale of ten feet, by which the entire work was measured

Palladio, Andrea. Four Books on Architecture. State Publishing House of Fine Literature, Music and Art, Prague 1958

I quattro libri dell' architettura di Andrea Palladio, Venice, Appresso Dominico de' Franceschi, 1570

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment