Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

“I try to relate a solid form with compositional methods to a way of life that will take place in the given space and to the local community. The anchor for selecting solutions to these problems is the autonomous architectural theory based on the composition of basic geometric forms, my own views on life, and my feeling as a Japanese person.”

Renowned cultural institutions are thriving in the second largest American state. To refresh your memory, I would mention the famous Museum District in Houston and Judd's Marfa. Even Fort Worth, the sixth largest city in Texas, has upheld its museum reputation. Two years before his death, Louis Kahn built one of the most significant structures of the second half of the 20th century here, the Kimbell Art Museum, and a few meters away, Philip Johnson created the Amon Carter Museum (by the way, the entire Carter Museum complex is the result of Johnson's forty years of work. The latest part was opened on October 21, 2001). Less than a year ago, the Japanese architect Tadao Ando signed onto such an honorable and binding environment.

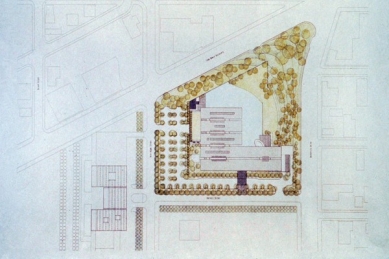

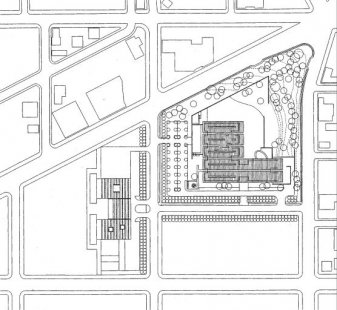

In 1996, the board of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth acquired an eleven-acre plot right across from the Kimbell Art Museum. Tadao Ando was commissioned to design the building, even though he had only two smaller projects to his name in America so far. Many of Ando's early sketches demonstrate the power of the neighboring museum by Louis Kahn. It was like asking someone to build a new church right next to the cathedral in Chartres. However, Ando is a strong enough personality who would not stoop to quoting or copying the pattern from the neighboring plot. His works are always polished and deliberate. He is not afraid of strict simplicity, even with large projects. Fundamentally, Kahn and Ando have much in common, which is why the buildings understand each other so well. They do not compete with one another. One does not overshadow the other.

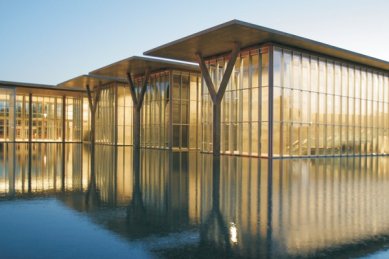

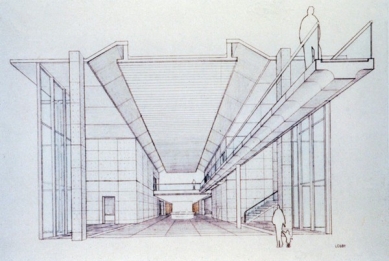

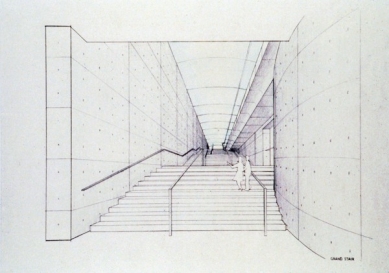

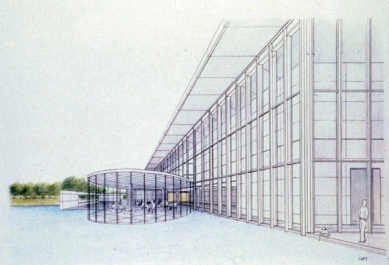

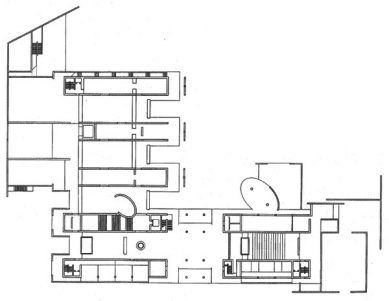

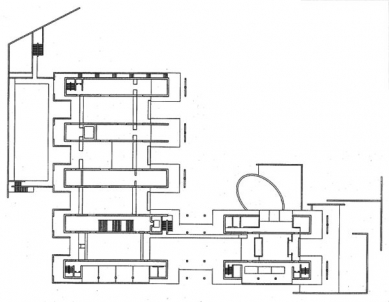

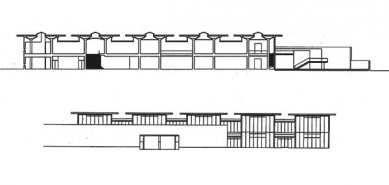

The new museum consists of five blocks lying parallel to each other. Three of them are shorter, and two are longer. Each one is composed of two shells – a forty-foot (11.2 meter) high outer steel-glass shell and equally high inner concrete walls. The free space stretching the entire height of the building between these two shells serves for resting and observing the building and its surroundings. While the glass facade freely allows daylight to penetrate the interior, the concrete walls and overhanging roof protect the exhibited objects from direct sunlight.

Entrance spaces, an auditorium for 250 people, and a shop are incorporated into the two longer rectangular volumes. The elliptical mass protruding from the rectangular grid houses a restaurant and café. From here, visitors are offered a magnificent view of the three shorter volumes, within which there are gallery rooms on the two floors. The overhanging flat concrete roof is supported by concrete columns in the shape of the letter Y, standing in a shallow pool surrounding the museum. The artificially created water surface tempers the hot Texas weather, filters external noise, and also acts as a mirror reflecting the museum's structure. The changing weather brings a different image of the museum on the water's surface each time. A parking lot (with an unusually small number of spaces by Texas standards) populated with trees and a park separates the building from the passing highway. Rising above the edge of the parking spaces, a metal sculpture by Richard Serra towers over the museum.

Tadao Ando

Renowned cultural institutions are thriving in the second largest American state. To refresh your memory, I would mention the famous Museum District in Houston and Judd's Marfa. Even Fort Worth, the sixth largest city in Texas, has upheld its museum reputation. Two years before his death, Louis Kahn built one of the most significant structures of the second half of the 20th century here, the Kimbell Art Museum, and a few meters away, Philip Johnson created the Amon Carter Museum (by the way, the entire Carter Museum complex is the result of Johnson's forty years of work. The latest part was opened on October 21, 2001). Less than a year ago, the Japanese architect Tadao Ando signed onto such an honorable and binding environment.

In 1996, the board of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth acquired an eleven-acre plot right across from the Kimbell Art Museum. Tadao Ando was commissioned to design the building, even though he had only two smaller projects to his name in America so far. Many of Ando's early sketches demonstrate the power of the neighboring museum by Louis Kahn. It was like asking someone to build a new church right next to the cathedral in Chartres. However, Ando is a strong enough personality who would not stoop to quoting or copying the pattern from the neighboring plot. His works are always polished and deliberate. He is not afraid of strict simplicity, even with large projects. Fundamentally, Kahn and Ando have much in common, which is why the buildings understand each other so well. They do not compete with one another. One does not overshadow the other.

The new museum consists of five blocks lying parallel to each other. Three of them are shorter, and two are longer. Each one is composed of two shells – a forty-foot (11.2 meter) high outer steel-glass shell and equally high inner concrete walls. The free space stretching the entire height of the building between these two shells serves for resting and observing the building and its surroundings. While the glass facade freely allows daylight to penetrate the interior, the concrete walls and overhanging roof protect the exhibited objects from direct sunlight.

Entrance spaces, an auditorium for 250 people, and a shop are incorporated into the two longer rectangular volumes. The elliptical mass protruding from the rectangular grid houses a restaurant and café. From here, visitors are offered a magnificent view of the three shorter volumes, within which there are gallery rooms on the two floors. The overhanging flat concrete roof is supported by concrete columns in the shape of the letter Y, standing in a shallow pool surrounding the museum. The artificially created water surface tempers the hot Texas weather, filters external noise, and also acts as a mirror reflecting the museum's structure. The changing weather brings a different image of the museum on the water's surface each time. A parking lot (with an unusually small number of spaces by Texas standards) populated with trees and a park separates the building from the passing highway. Rising above the edge of the parking spaces, a metal sculpture by Richard Serra towers over the museum.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

5 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Texas

KD

11.12.05 12:10

Texas

Petr Šmídek

11.12.05 03:27

šéfredaktor

Jan Kratochvíl

11.12.05 03:32

redaktor

Martin Rosa

11.12.05 03:08

nepřekřičuje..

m

15.03.08 06:23

show all comments