Ossuary for the Fallen of WWI

<translation>Kosnice Victims of World War I</translation>

Aleksander Ignajtović

Yugoslavism through the Syntax of Classicism: The Memorials to the First World War in Belgrade and Ljubljana, 1931-1939

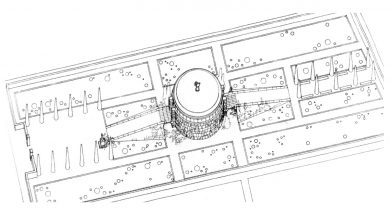

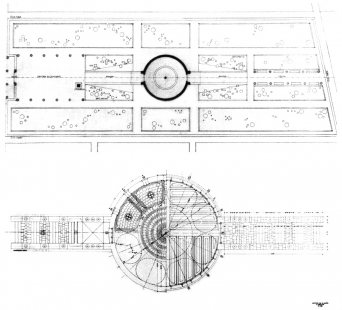

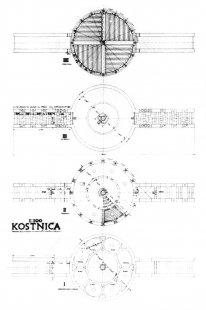

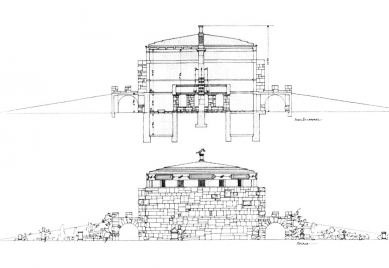

Contrary to the idea that classical forms typically refer to the universal and invariable, as well as the oversimplified identification of classicism with cultural conservatism that supposedly went hand in hand with the political authoritarianism of the 1920s and 1930s, the position of classical architecture in interwar Europe was much more complex. This is perhaps best witnessed in numerous monuments and memorials to WWI, which are distinguished not only by the diversity of ways in which architects and artists experimented with the classical language of forms, but also by their social and political connotations. Unlike most countries, both newly established after the First World War and old nation-states, the multi-ethnic Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (from 1929 the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) had its own ideological raison d'être in the idea of a simultaneously composite and primordial nation. The ideology of Yugoslavism was a complex set of ideas referring to the multi-ethnic community of Yugoslays — sharply divided not only by culture, but also by their experiences in the Great War — seeking a cohesive national culture. The idea of a single, primordial nation, united by common descent and future prospects, was based on the mythologization of the people's original unity, as well as the obliteration of cultural, religious and, most importantly, political differences. In this respect, the symbolic legacy of classicism had much to offer to the cultural imagination of Yugoslavism. From Roman Verhovskoy's Monument and Crypt to the Defenders of Belgrade (1931) or the nearby Memorial to the Russian Soldiers Fallen in the War (1934), Ivan Mearović's Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (1934-1938) to Edvard Ravnikar's War Victims Ossuary (1937-1939), the classicizing vocabulary of the state-sponsored monuments referred not only to the great synthetic ideas like victimhood and patriotism, but also connoted a nostalgia for an integrated community in a country deeply divided by the traumatic experience of the Great War. At the same time, the universalistic overtones and cultural legacy of this politically employed classicism corresponded to the ongoing supra-ethnic imagination of the Yugoslav nation and its common ancient Greek and Roman legacy, which preoccupied the Yugoslav elites.

Aleksander Ignjatović is an architectural historian and an Associate Professor at the University of Belgrade. His research interests lie in the cultural history of architecture and the visual arts. Most of his work currently centers on the relationship between architecture, visual culture, ideology and political power, especially in the Balkans during the 19' and 20th centuries, yet always within a broader European context.

Yugoslavism through the Syntax of Classicism: The Memorials to the First World War in Belgrade and Ljubljana, 1931-1939

Contrary to the idea that classical forms typically refer to the universal and invariable, as well as the oversimplified identification of classicism with cultural conservatism that supposedly went hand in hand with the political authoritarianism of the 1920s and 1930s, the position of classical architecture in interwar Europe was much more complex. This is perhaps best witnessed in numerous monuments and memorials to WWI, which are distinguished not only by the diversity of ways in which architects and artists experimented with the classical language of forms, but also by their social and political connotations. Unlike most countries, both newly established after the First World War and old nation-states, the multi-ethnic Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (from 1929 the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) had its own ideological raison d'être in the idea of a simultaneously composite and primordial nation. The ideology of Yugoslavism was a complex set of ideas referring to the multi-ethnic community of Yugoslays — sharply divided not only by culture, but also by their experiences in the Great War — seeking a cohesive national culture. The idea of a single, primordial nation, united by common descent and future prospects, was based on the mythologization of the people's original unity, as well as the obliteration of cultural, religious and, most importantly, political differences. In this respect, the symbolic legacy of classicism had much to offer to the cultural imagination of Yugoslavism. From Roman Verhovskoy's Monument and Crypt to the Defenders of Belgrade (1931) or the nearby Memorial to the Russian Soldiers Fallen in the War (1934), Ivan Mearović's Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (1934-1938) to Edvard Ravnikar's War Victims Ossuary (1937-1939), the classicizing vocabulary of the state-sponsored monuments referred not only to the great synthetic ideas like victimhood and patriotism, but also connoted a nostalgia for an integrated community in a country deeply divided by the traumatic experience of the Great War. At the same time, the universalistic overtones and cultural legacy of this politically employed classicism corresponded to the ongoing supra-ethnic imagination of the Yugoslav nation and its common ancient Greek and Roman legacy, which preoccupied the Yugoslav elites.

Aleksander Ignjatović is an architectural historian and an Associate Professor at the University of Belgrade. His research interests lie in the cultural history of architecture and the visual arts. Most of his work currently centers on the relationship between architecture, visual culture, ideology and political power, especially in the Balkans during the 19' and 20th centuries, yet always within a broader European context.

0 comments

add comment