Schullin Jewelry Shop

dnes Caesars Juwelen

Ornament is no crime

It is the Vienna of Freud, more than that of Loos, that must invade Hans Hollein's mind and quicken his work. In his series of Viennese travel agencies (P/A, Dec. 1979, pp.76-79), haunting landscapes of fantasy and dreams unfold. In the less haunting but more intense Schullin jewelry shop, recently completed, primitive longings are encouraged within an aura of exoticism and shameless indulgence. In this shop, down the street from the 1910 Loos House and across from Hollein's more chaste candle shop of 1966, ornament is both message and medium.

Hollein has taken the basic shell of a 19th Century building, corrected it slightly, and painted it white, and then has superimposed a clearly differentiated layer of elements not only functional but fantastic and luxurious. Paradoxically for a jewelry shop (and quite intentionally), he has used materials in flagrant disregard of their real value: Some are precious and some are common, but all, glowing or glittering, tease the visitor with an impression of wealth and mystery. Real marble is used in th patterned floor, but in the black-curtained backworld of the safe, under a mock skylight, plastic laminate pretends to be marble. Real bronze is used as an arch/guillotine over the entrance, but a headless "bronzed" African bust is in fact plastic. Burled wood encases the cabinets, but can be confused with the similarly colored, similarly patterned verona marble beside it. Brass gleams golden on the winged glass cask holding the "crown jewels", while real gold coats nonskid metal treads serving as light reflectors atop the standards marking the visitor's procession inward.

Unlike many architects working in Vienna now, Hollein does not aim for low-key intervention. He does not attempt to invent work that blends into Vienna's historical continuum. This is especially evident in Schullin, where there is a clear distinction between the whitewashed shell of the existing building and the flash and glitter of Hollein's insertion. Viennese allusions are included, to be sure - the Hoffmannesque doors, for example - but they are points, not counterpoints. While Hollein's doctrines two decades ago sparked the anti-elitist, anti-Modernist movement responsible, he says, for the current Post-Modern activities in Vienna, he has developed differently from his younger colleagues. Hermann Czech and Missing Link, for example, more slowly and painstakingly to etch details that add u to a sum reminiscent of - and sometimes at first glance indistinguishable from - vernacular Austrian architecture. Hollein's movements are more sweeping: his references, both architectural and psychological, are farther reaching, and the ambience he creates is intentionally gaudier.

The Schullin shop on fashionable Kohlmarkt stands in the two end bays of a commercial/ residential building, of which the ground floor's central bays have been almost totally transformed by glazed shop windows. Only the bays at either end have retained a certain solidity, and the Hollein intervention only slightly violates the original solid/void relationship by penetrating the wall to provide a central doorway. This is flanked by the two large existing openings, both now serving as show windows. At either side, a tiny window has been added, a small orb emphasizing the preciousness of its contents, with a keystone above that suggests, overliterally, the cross section of a ring. A neon arc over the second story ties the two floors together, but undoubtedly the strongest element on the facade is the wood, brass, and bronze door frame - a triumphal arch and primitive weapon, Napoleon's hat and Hannibal's hatchet. The wood poles are each single trunks hollowed to minimize cracking. Their tips are brass rings and the symmetrical "blade" is oxidized bronze, from which flutters a red flag evoking imagery of blood from both Christian and pagan rituals. (Obvious political interpretations necessitated the flag's removal during the recent election campaign.).

One enters - somewhat threatened but nonetheless intrigued by the "arch"- through the deep slot and past the door punctured in Hoffmannesque perspective; the large, square upper openings give views into the shop, and the smaller lower square windows provide some privacy for the shoppers. The door handle contradicts the rectilinearity of the door; it is a malevolent cast bronze serpent executed by sculptor Gero Schwanberg.

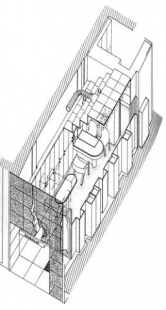

Inside, one moves through a long, marble-floored front sales room whose flanking rows of light standards and diagonally patterned floor encourage the progression to a sqarish back room where the sparcity of pattern, the upholstered furniture, and the symmetrically curtained openings slow one's movements. The ultimate sanctuary is a second-story showroom, carpeted, lush and exclusive (but not yet complete).

The front room's polished finish is pulled tightly across a savage heart: Its floor beats in a syncopated rhythm, its cabinets reveal the reddish glow of the root of the African Wawona tree, and its mahogany-poled, gold-plumed lamps flank the space like African tribesmen lining the parade route of a visiting monarch. Clear mirrored strips create slender patterned cross-axes, blocked by white marble pyramids.

The first room, primitive, gives way to a second one as ghostly and ascetic as a Roman priest. The openings between them are high and narrow, and their corners are carved away, in traditional Viennese manner, to form pointed reveals and to insist upon the thickness of the enclosing cavern. Through the principal opening one sees more light standards, but these are different from the earlier ones. There are but three of them, diagonally placed, and they are not ruddy, nor of wood, but are white faux marbre. Their heads (industrial lamps) do not flare but, from their heights, bow in priestly humility, while their "ehalos"e cast light upwards to the vaulted ceiling. Beyond these three attendants, one glimpses the tall black curtains shrouding the ultimate openings, one to the upper floor, one to the safe.

Once in the second room, one is invited to rest, either in the chairs grouped upon the central square of white marble flooring, wrested from the movement of the actively patterned floor around it, or on the corner divan, upholstered in a deep-colored pattern and framed in burled Wawona. In the opposite corner, the jeweler performs his ministrations at a wood desk beside a wide, gold leafed column, ritualistic in implication and functional in fact - it is an air duct. Both wood corner elements - the divan and the desk - seem to hover rather hesitantly in the large, white space.

In Schullin, Hollein creates a world of fantasies - of richness, of primitive desires, and finally, of reassuring holiness. Gems have awed savages and adorned monarchs, and here, in a small shop in Vienna, where the differences between real value and fakery are blurred, gems arouse and then assuage the consumer passions of burgers who become, via pearls, angels. The complex subconscious process involves inspiration, ritual, pretense, and moral reassurance. Through the canny employment of rich and common materials - using both silk and sow's ears - and the invention of curious forms from psychological netherworlds, Hollein has produced a setting ideally matching and fostering the process.

It is the Vienna of Freud, more than that of Loos, that must invade Hans Hollein's mind and quicken his work. In his series of Viennese travel agencies (P/A, Dec. 1979, pp.76-79), haunting landscapes of fantasy and dreams unfold. In the less haunting but more intense Schullin jewelry shop, recently completed, primitive longings are encouraged within an aura of exoticism and shameless indulgence. In this shop, down the street from the 1910 Loos House and across from Hollein's more chaste candle shop of 1966, ornament is both message and medium.

Hollein has taken the basic shell of a 19th Century building, corrected it slightly, and painted it white, and then has superimposed a clearly differentiated layer of elements not only functional but fantastic and luxurious. Paradoxically for a jewelry shop (and quite intentionally), he has used materials in flagrant disregard of their real value: Some are precious and some are common, but all, glowing or glittering, tease the visitor with an impression of wealth and mystery. Real marble is used in th patterned floor, but in the black-curtained backworld of the safe, under a mock skylight, plastic laminate pretends to be marble. Real bronze is used as an arch/guillotine over the entrance, but a headless "bronzed" African bust is in fact plastic. Burled wood encases the cabinets, but can be confused with the similarly colored, similarly patterned verona marble beside it. Brass gleams golden on the winged glass cask holding the "crown jewels", while real gold coats nonskid metal treads serving as light reflectors atop the standards marking the visitor's procession inward.

Unlike many architects working in Vienna now, Hollein does not aim for low-key intervention. He does not attempt to invent work that blends into Vienna's historical continuum. This is especially evident in Schullin, where there is a clear distinction between the whitewashed shell of the existing building and the flash and glitter of Hollein's insertion. Viennese allusions are included, to be sure - the Hoffmannesque doors, for example - but they are points, not counterpoints. While Hollein's doctrines two decades ago sparked the anti-elitist, anti-Modernist movement responsible, he says, for the current Post-Modern activities in Vienna, he has developed differently from his younger colleagues. Hermann Czech and Missing Link, for example, more slowly and painstakingly to etch details that add u to a sum reminiscent of - and sometimes at first glance indistinguishable from - vernacular Austrian architecture. Hollein's movements are more sweeping: his references, both architectural and psychological, are farther reaching, and the ambience he creates is intentionally gaudier.

The Schullin shop on fashionable Kohlmarkt stands in the two end bays of a commercial/ residential building, of which the ground floor's central bays have been almost totally transformed by glazed shop windows. Only the bays at either end have retained a certain solidity, and the Hollein intervention only slightly violates the original solid/void relationship by penetrating the wall to provide a central doorway. This is flanked by the two large existing openings, both now serving as show windows. At either side, a tiny window has been added, a small orb emphasizing the preciousness of its contents, with a keystone above that suggests, overliterally, the cross section of a ring. A neon arc over the second story ties the two floors together, but undoubtedly the strongest element on the facade is the wood, brass, and bronze door frame - a triumphal arch and primitive weapon, Napoleon's hat and Hannibal's hatchet. The wood poles are each single trunks hollowed to minimize cracking. Their tips are brass rings and the symmetrical "blade" is oxidized bronze, from which flutters a red flag evoking imagery of blood from both Christian and pagan rituals. (Obvious political interpretations necessitated the flag's removal during the recent election campaign.).

One enters - somewhat threatened but nonetheless intrigued by the "arch"- through the deep slot and past the door punctured in Hoffmannesque perspective; the large, square upper openings give views into the shop, and the smaller lower square windows provide some privacy for the shoppers. The door handle contradicts the rectilinearity of the door; it is a malevolent cast bronze serpent executed by sculptor Gero Schwanberg.

Inside, one moves through a long, marble-floored front sales room whose flanking rows of light standards and diagonally patterned floor encourage the progression to a sqarish back room where the sparcity of pattern, the upholstered furniture, and the symmetrically curtained openings slow one's movements. The ultimate sanctuary is a second-story showroom, carpeted, lush and exclusive (but not yet complete).

The front room's polished finish is pulled tightly across a savage heart: Its floor beats in a syncopated rhythm, its cabinets reveal the reddish glow of the root of the African Wawona tree, and its mahogany-poled, gold-plumed lamps flank the space like African tribesmen lining the parade route of a visiting monarch. Clear mirrored strips create slender patterned cross-axes, blocked by white marble pyramids.

The first room, primitive, gives way to a second one as ghostly and ascetic as a Roman priest. The openings between them are high and narrow, and their corners are carved away, in traditional Viennese manner, to form pointed reveals and to insist upon the thickness of the enclosing cavern. Through the principal opening one sees more light standards, but these are different from the earlier ones. There are but three of them, diagonally placed, and they are not ruddy, nor of wood, but are white faux marbre. Their heads (industrial lamps) do not flare but, from their heights, bow in priestly humility, while their "ehalos"e cast light upwards to the vaulted ceiling. Beyond these three attendants, one glimpses the tall black curtains shrouding the ultimate openings, one to the upper floor, one to the safe.

Once in the second room, one is invited to rest, either in the chairs grouped upon the central square of white marble flooring, wrested from the movement of the actively patterned floor around it, or on the corner divan, upholstered in a deep-colored pattern and framed in burled Wawona. In the opposite corner, the jeweler performs his ministrations at a wood desk beside a wide, gold leafed column, ritualistic in implication and functional in fact - it is an air duct. Both wood corner elements - the divan and the desk - seem to hover rather hesitantly in the large, white space.

In Schullin, Hollein creates a world of fantasies - of richness, of primitive desires, and finally, of reassuring holiness. Gems have awed savages and adorned monarchs, and here, in a small shop in Vienna, where the differences between real value and fakery are blurred, gems arouse and then assuage the consumer passions of burgers who become, via pearls, angels. The complex subconscious process involves inspiration, ritual, pretense, and moral reassurance. Through the canny employment of rich and common materials - using both silk and sow's ears - and the invention of curious forms from psychological netherworlds, Hollein has produced a setting ideally matching and fostering the process.

Susan Doubilet in Progressive Architecture, New York 6/1983, p.76-79

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

dobre jmeno

Ernest

30.08.12 10:47

show all comments